BATAK RELIGION

Most Bataks are Protestant Christians but a significant number are Muslim. Beliefs in spirits remain strong even though many speak of an “Age of Darkness” that existed before their ancestors were converted to Islam and Christianity. There is some merging of Islamic and Christian beliefs. Traditional animist beliefs are called Sipelebegu or Parbegu. According to Joshua Project about 97 percent of Toba Batak and Silindung Batak, 65 percent of Simalungun Batak, 70 percent of Karo Batak and Pakpak Batak and 79 percent of Dairi Batak are Christians. Around 90 percent of Angkolo Batak are Muslims.

For more than a century, the Toba Batak have been predominantly Protestant Christian, while the Angkola and Mandailing Batak embraced Islam several decades earlier. The indigenous animist religion, known as Pebegu, remains strongest among the Karo Batak, where it claims about 57 percent of adherents, though many describe their practice as largely secular. Among the Karo, roughly 12 percent are Muslim and about 31 percent Christian; conversions were relatively limited until 1965, when the suppression of communism required all Indonesians to formally identify with a recognized religion. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The self-governing Toba Protestant church, the Huria Kristen Batak Protestant (HKBP), has grown into the largest Christian denomination in Indonesia and one of its most influential. Simalungun and Karo Protestants have also established their own independent churches. Catholics make up about 10 percent of the Batak population, with missionary activity expanding mainly after Indonesian independence. Despite these affiliations, many Christian and Muslim Batak continue to observe elements of traditional religious belief alongside their adopted faiths.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BATAKS: GROUPS, HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND WERE THEY REALLY CANNIBALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, KINSHIP factsanddetails.com

BATAK LIFE: HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

BATAK CULTURE: MUSIC, ART, FOLKLORE, CRAFTS AND LIFE-SIZE PUPPETS factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SUMATRA factsanddetails.com

SUMATRA: HISTORY, EARLY HUMANS, GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE factsanddetails.com

LAKE TOBA AREA: BATAKS, SAMOSIR ISLAND AND THE TOBA SUPERVOLCANO ERUPTION 71,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

Traditional Batak Religion

Traditional Batak religion recognizes many deities but places greater emphasis on spirits closely connected to human life. Two gods are especially prominent. Boru Saniang Naga, the goddess of rivers and lakes, must be honored before fishing, farming, or traveling by boat. Boraspati ni Tano, a fertility god often depicted in the form of a lizard on house façades, must be appeased whenever the soil is worked. Before the Toba Batak embraced Protestant Christianity, they believed in an all powerful god, Mulajadi Nabolon, who had power over the sky and conveyed his power in Debata Natolu .[Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

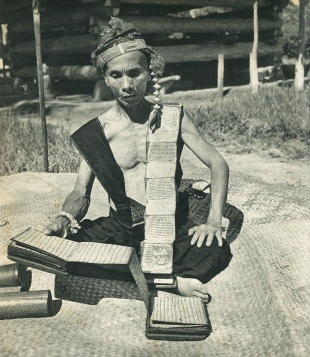

Religious specialists include guru sibaso, female spirit mediums, and datu, male ritual experts who undergo demanding apprenticeships to master occult knowledge. Their teachings are recorded in pustaha, folding bark books written in Batak script that contain instructions on magic, divination, and traditional medicine.

Divining calendars known as “porhalaan”—with 12 months of 30 days each—are engraved on sacred bones or cylinders of bamboo and used in determining auspicious days for activities such planting rice. During the funerals, Batak chieftains used to use human-sized puppets mounted on wheeled platforms operated by a shaman who pulled wires and levers to make the effigy "weep tears, gnash its teeth, drag priests and speak in a voice of the departed." The puppets were dressed in possessions of the deceased and were used to revive the souls of the dead and communicate with the dead. Christian and Muslim leaders and colonial officials discouraged such practices as blasphemous. ~

Traditional Batak Beliefs

Traditional Batak beliefs center on a spiritual understanding that the universe is divided into three realms: 1) the upper world where the God’s residesl 2) the middle world which belongs to humans; and 3) the lower world which is home to ghosts and demons. Medical care in Batak culture focuses on the condition of the soul. It is believed that sickness is caused when the soul flees the body in which case a traditional healer is needed to help call the wandering soul back to the patient.

Traditional beliefs manifest themselves in: 1) participation in adat (local customary practices) ceremonies and rituals, 2) a fear of sorcery, witchcraft and poisoning, 3) the practice of spiritual healing and 4) a belief in indi” — the idea that illnesses are cased when the soul leaves the body. Sacrifices are regularly performed for indi to make sure the soul is happy and stays near the body. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

Concerning the soul and the spirit, the Batak Toba identify three concepts: 1) Tondi, the soul or spirit of a person is the force that gives life to man. If Tondi leaves the body of a person, then that person will get sick or die, and a ceremony called mangalap sombaon is necessary to bring the Tondi back. 2) Sahala is the soul or spirit of one's own power. Everybody has Tondi, but not everyone has Sahala. Sahala with Sumanta, luck or magic that of the king or the hula-hula. 3) Begu is the Tondi of people have died. It has the same behavior as human behavior, but turns up only at night. [Source: ibdo.blogspot.jp]

Tondi is called tendi among the Karo. It is the life force present in humans as well as in rice and iron. The creator god Mula Jadi Na Bolon bestows each person’s tondi before birth, and this life force also determines an individual’s destiny. The tondi is not permanently bound to the body; it may wander or be captured by stronger spirits. Illness occurs when the tondi separates from the body, and death can follow if it cannot be coaxed or summoned back through offerings or ritual mediation. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

At death, the tondi vanishes, releasing the begu, or essential soul. The begu lingers near the former home or burial place and may communicate with the living, sometimes through dreams or misfortune. Certain individuals—such as infants who die very young, victims of violence or accidents, or unmarried young women—become protective begu for their families. Through elaborate funerary rituals, the begu of powerful individuals can be elevated to sumangot, revered ancestors around whom new subclans may form. With further rites, these ancestors may become sombaon, highly honored forebears from ten to twelve generations past, believed to dwell in remote or eerie places such as mountains and dense forests. Neglected begu may turn hostile, while all begu are ultimately mortal, said to “die” seven times before finally transforming into a blade of grass.

Datu

Among the most powerful figures in Batak communities have been ritual specialists known as datu. Usually drawn from the village’s founding lineage and exclusively male, datu were experts in religious knowledge. They were believed to cure illness, communicate with the spirits of the dead, and determine auspicious days for rituals and major events. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Datu acted as intermediaries between the human and spiritual worlds. Much of Toba Batak sacred art centered on the creation and adornment of objects that would be used by the datu for divination, curing ceremonies, malevolent magic, and other rituals. Among the most important were ceremonial staffs, books of ritual knowledge known as pustaha and a variety of containers used to hold magical substances, such as this perminangken.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Datu were second in rank only to the village headman. They performed both benign and malevolent magic using a variety of ritual paraphernalia. These objects were primarily used to hold pukpuk, the most potent supernatural substance in the datu's magical arsenal, which was most commonly derived from the body of a ritually slain human victim whose captured spirit (pangulubalang) served the datu as a supernatural helper. However, the instructions for preparing pukpuk recorded in some pushtaha indicate that animals rather than humans could be used.

Batak Funerals and Tombs

Even among Batak Christians, many traditional funerary customs remain important. One such practice is the procession of masked dancers who accompany the coffin to the grave. The large masks—depicting a man, a woman, and either a hornbill or a horse—are paired with oversized wooden hands and are placed on top of the coffin to protect the deceased from harmful spirits. Because proper funeral rites must be performed by a son, Toba families without sons traditionally use a si gal-gale, a life-sized wooden figure with movable limbs, to stand in for a son who was never born or who died earlier. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Burial practices vary by status. Poorer individuals are simply wrapped in mats and buried, while the wealthy are given elaborate coffins, often massive in size, whose construction may begin long before death. These unfinished coffins are commonly stored beneath houses. The Karo are especially known for the pelangkah, a boat-shaped coffin decorated with a hornbill head. In some Karo and Dairi communities, the body of an important person was once placed in a special structure and cremated after a year. More commonly, Batak groups exhume the bones of prominent individuals for reburial in large stone sarcophagi, often carved with a singa (lion) on the front. Today, such tombs are usually built of concrete rather than stone and may include large statues.

Some Christian Batak families construct concrete tombs modeled on traditional houses, richly carved, brightly painted, and marked with a cross and the name of the deceased. Over time, however, many Batak—especially after conversion to Islam and Christianity—have abandoned sculpted grave markers. In northern Toba areas, families now often erect tall concrete tugu, or memorial monuments, funded by relatives working in cities. These modern, geometric structures typically support a statue of the clan founder and continue to signal wealth, status, and a wider, more cosmopolitan outlook, even as their form reflects contemporary tastes. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Batak Burials and Reburials

Among the Batak, immediately following death, ritual acts symbolically separate the deceased from relatives, culminating in a perumah begu ceremony in which a ritual specialist formally informs the spirit that it must depart. Burial practices vary by status: wealthy families use elaborately carved coffins and may keep them near the home until later rites, while poorer families use simpler coffins or mats. Funerals involve music, gunfire, and symbolic actions meant to prevent the spirit from returning to the village, with special burial positions reserved for ritual specialists and those who died unnaturally. [Source: Wikipedia]

A central feature of Batak mortuary custom is secondary burial, in which ancestors’ bones are exhumed years later, ritually cleaned, mourned, and reinterred in a communal bone house (tugu or tambak). Artur Simon and T. S. Barthel wrote in 1982: "On the morning of the first day of the festival the graves in the cemetery are opened and the bones of the ancestors that are still there are removed. The unearthing of the skulls is presented as especially moving.

The bones are collected in baskets lined with white cloth and then ritually cleaned by the women using the juice of various citrus fruits. The exhumation and cleaning of the bones is accompanied by the singing of laments. The bones are kept in the baskets in the tugu until the next morning, when the remains are wrapped in traditional cloths (ulos) and transferred from the baskets to small wooden coffins. After long speeches and a communal prayer the coffins are nailed down and placed in the chambers of the tugu. A feast consisting of meat and rice follows and traditional dances are performed."

The multi-day reburial ceremony strengthens lineage ties and honors prominent ancestors. Reburial also elevates the spiritual status of the dead: through increasingly elaborate ceremonies and feasts, a spirit may be raised from begu to sumangot, and eventually to sombaon, powerful ancestral spirits believed to protect and bless their descendants while reinforcing kinship identity and social hierarchy.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025