SUMATRA

Sumatra is a huge Indonesian island southwest of Southeast Asia and east of Java. Situated just a few kilometers across the important Straits of Malacca from Singapore and Malaysia, it is covered by mountains and plateaus in the west and wide, flat, swampy lowlands and brown meandering rivers in the east. Sumatra remains a wild place with some stunning scenery and beautiful places despite undergoing rapid development in recent decades. Even though vast tracts of lowland forest have been cleared, large areas of forests till remain in the highlands. Some of the highest concentrations of large animals in Asia are found in Sumatra's mountain parks. Offshore are islands with some of the world’s best surfing spots. [Source: Harvey Arden, National Geographic, March 1981]

Sumatra is Indonesia’s second most populous province. It is home to 61 million people (2020s), about 20 percent of Indonesia’s population, but is much less densely populated than Java or Bali. Although its is almost four times the size of Java it has less than a quarter of its population, The highest concentration of people are west of Medan on the northeast coast. Important ethnic groups include the Acehnese and Gayo-Alas, who live in the northern part of Sumatra; the Batak who live around Lake Toba; the Minangkabau, who live in western Sumatra; Malays, who dominate the east, across the Straits of Malacca from Malaysia. The Ogan-Besemah live in the south.

Sumatra island is rich in resources and has large oil and gas deposits and huge rubber and palm oil plantations. At one time it generated 70 percent of Indonesia’s export income. Three quarters of Indonesia’s oil is extracted from oil fields around the Sumatran towns of Jambi, Palembang, and Pekanbaru. Lhokseumawe on the east cast of Aceh is the center of Indonesia’s natural gas industry. Timber as also an important industry as the deforestation figures for the island attest. Pepper has traditionally been an important crop. Tea, coffee, cocoa beans and tobacco are also grown.

In the 1950s there was some discussion about making Sumatra a separate state but not much happened on that. Although nearly all of the approximately 20 ethnolinguistic groups of Sumatra are devout practitioners of Islam, they nonetheless differ strikingly from one another, particularly in their family structures.

Places of note include Lake Toba, a beautiful volcanic lake in the north; Padang, central Sumatra's largest city and center of the Minangkabau people (a matriarchal society); Palembang, site of a refinery and large oil installations; and an elephant training center near Lampung in southern Sumatra. Most places are visited using minibuses or cars with a driver. Many roads are either dangerously congested or in poor conditions and traffic accidents are real danger. In the 1950s there was some discussion about making Sumatra a separate country but obviously not much came of it. Although nearly all of the approximately 20 ethnic groups of Sumatra are Muslim, their level of piety varies with the Acehnese arguably being the most devout and their cultures and customs, particularly their family structures, also vary greatly. About 90 percent of Sumatrans are Muslim. The rest are mostly Christians — Protestants and Catholics — and some Hindus and Buddhists. [Source: Cities of the World, Gale Group Inc., 2002, adapted from a 2001 U.S. State Department report]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SUMATRA factsanddetails.com

BATAKS: GROUPS, HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND WERE THEY REALLY CANNIBALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, BURIALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, KINSHIP factsanddetails.com

BATAK LIFE: HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

BATAK CULTURE: MUSIC, ART, FOLKLORE, CRAFTS AND LIFE-SIZE PUPPETS factsanddetails.com

LAKE TOBA AREA: BATAKS, SAMOSIR ISLAND AND THE TOBA SUPERVOLCANO ERUPTION 71,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, SOCIETY, FAMILIES factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI RELIGION CHRISTIANITY, SPIRITS, SHAMAN factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI LIFE: HOUSING, FOOD, HUNTING, MODERNIZATION factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI TATTOOS factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI ISLANDS: RAIN FORESTS, SURFING, UNIQUE TRIBES factsanddetails.com

Geography and Climate of Sumatra

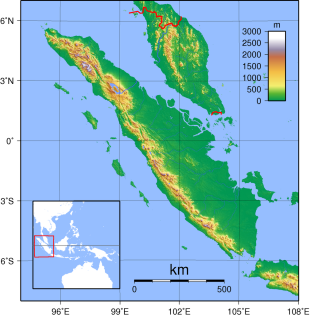

Sumatra is the world’s sixth largest island, covering 482,287 square kilometers (182,812 square miles).. Nearly bisected by the equator, it is 1,800 kilometers (1,100 miles) long and accounts for 24.7 percent of Indonesia's land area. A long chain of mountains—the Bukit Barisan—run northwest-southeast and parallel to the west coast of the island. There are around 100 volcanos on the island, with 15 or so of them active ones. Many are over 3000 meters. The highest mountain in Indonesia outside Papua is the 3805-meter-high Sumatran volcano Gunung Kerinci.

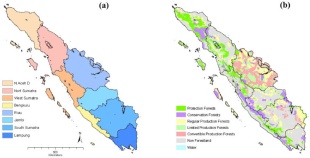

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia and is part of Sundaland, a vast, sunken landmass in Southeast Asia that connected Borneo, Java, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula during glacial periods when sea levels were lower, creating a large, exposed continental shelf. Sumatra is divided into ten provinces: Aceh, North Sumatra, West Sumatra, Riau, Riau Islands, Jambi, Bengkulu, South Sumatra, Lampung, and the Bangka Belitung Islands, each with its own distinct culture. The Sumatra are aincludes several nearby island groups, such as Simeulue, Nias, the Mentawai Islands, Enggano, the Riau Islands, Bangka Belitung, and the Krakatoa archipelago.

The equator crosses central Sumatra.The Indian Ocean borders Sumatra’s northwestern, western, and southwestern coasts, with the islands of Simeulue, Nias, Mentawai, and Enggano lying offshore. To the northeast, the Strait of Malacca separates Sumatra from the Malay Peninsula, while to the southeast the Sunda Strait, which includes the Krakatoa archipelago, divides it from Java. Sumatra’s northern tip lies close to the Andaman Islands, and its southeastern waters include Bangka and Belitung, the Karimata Strait, and the Java Sea. The Bukit Barisan mountain range, dotted with active volcanoes, runs the length of the island, while the northeast consists largely of lowlands, swamps, mangrove forests, and extensive river systems.

The rainy season and dry seasons are not very distinct in northern Sumatra. The wet season runs from September to December. The hot, dry season is from May to August. In Medan the wettest months are October, November and December. The driest months are February, March and April but there isn’t that much difference between the wet months and the dry months. In southern Sumatra the rains start in November and reach their peak in January and February. The west coast of Sumatra is very wet, some places get above 400 centimeters of rain a year. Straddling the equator, Sumatra is very hot throughout the year. Fortunately the places visited by tourist tend to be in the highlands, where the climate is noticeably cooler, or near the oceans, which is tempered by sea breezes.

Sumatra Ecology and Animals

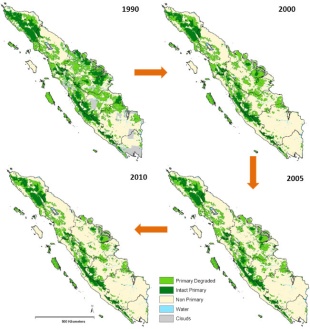

Sumatra was once dominated by dense rain forest. It still supports a rich diversity of plant and animal life, but nearly half of its tropical rainforest has disappeared over the past few decades. As a result, many species are now critically endangered, including the Sumatran ground cuckoo, Sumatran tiger, Sumatran elephant, Sumatran rhinoceros, and Sumatran orangutan. Large-scale deforestation has also contributed to fires and recurring seasonal haze that affects neighboring countries, notably during the severe Southeast Asian haze of 2013, which strained relations between Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. Because of the scale of environmental damage, scholars have increasingly described deforestation in Sumatra and other parts of Indonesia as an ecocide.

According to UNESCO: The biodiversity of the rain forest parks in Sumatra “is exceptional in terms of both species numbers and uniqueness. There are an estimated 10,000 species of plants, including 17 endemic genera. Animal diversity in TRHS is also impressive, with 201 mammal species and some 580 species of birds, of which 465 are resident and 21 are endemics. Of the mammal species, 22 are endemic to the Sundaland hotspot and 15 are confined to the Indonesian region, including the endemic Sumatran orangutan. Key mammal species also include the Sumatran tiger, rhino, elephant and Malayan sun-bear. [Source: UNESCO]

“Sumatra has a high level of endemism, which is well represented in the nominated sites. It is evidence of the land bridge/barrier between the Sumatran biota and that of mainland Asia due to changes in sea level. Some of the animal distributions may also be evidence of the effect of the Mount Toba tuff eruptions 75,000 years ago. The Sumatran orangutan for example, is not found south of Lake Toba nor the Asian tapir north of it. The altitudinal range and connections between the diverse habitats in these areas must have facilitated the ongoing ecological and biological evolution. Key mammals of the parks are the Sumatran tiger, Sumatran rhino, orangutan, Sumatran elephant; also Malayan sun-bear and the endemics Sumatran grizzled langur, Hoogerwerf's rat. Rare birds noted in the site's nomination are Sumatran ground cuckoo, Rueck's blue flycatcher, Storm's stork and white-winged duck.

The species listed below represent a small sample of iconic and/or International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red Listed animals and plants found in the property.

White-winged Wood Duck (Asarcornis scutulata)

Sumatran Ground-cuckoo (Carpococcyx viridis)

Green Turtle (Chelonia mydas)

Storm's Stork (Ciconia stormi)

Sunda Otter Civet

Rueck's Blue-flycatcher (Cyornis ruckii)

Sumatran Rhinoceros

Sumatran Elephant

Smooth-coated otters

Southern Pig-tailed Macaque (Macaca nemestrin)

All three parks that comprise the Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra are areas of very diverse habitat and exceptional biodiversity. Collectively, the three sites include more than 50 percent of the total plant diversity of Sumatra. At least 92 local endemic species have been identified in Gunung Leuser National Park. The property contains populations of both the world’s largest flower (Rafflesia arnoldi) and the tallest flower (Amorphophallustitanium). The relict lowland forests in the sites are very important for conservation of the plant and animal biodiversity of the rapidly disappearing lowland forests of Southeast Asia. Similarly, the montane forests, although less threatened, are very important for conservation of the distinctive montane vegetation of the property.

First Modern Humans in Indonesia — in Sumatra 70,000 Years Ago

Modern humans were in Sumatra at least 70,000 years. In a study published in Nature in August 2017, scientists said they had accurately dated two human teeth first discovered on the island of Sumatra in the late 19th century, showing our ancestors were living there between 73,000 and 63,000 years ago. Genetic studies have placed humans in Southeast Asia by 60,000 years ago, but the previous oldest fossil evidence dated to just 45,000 years. [Source: Hannah Osborne, Newsweek, Published August 9, 2017]

The teeth were found in the Lida Ajer cave in the Padang Highlands of Sumatra. They are the first evidence of humans in Indonesia and the first evidence of humans occupying a rainforest environment. The finding has surprised archaeologists. Kira Westaway, an environmental scientist at Macquarie University in Australia, told Newsweek, "The earliest evidence for modern humans using rainforests environments [was from] around 45,000 years ago in Niah Cave, Borneo."

These regions seem an unlikely place for early humans to live. "Rainforests are difficult environments to live in," says Westaway. "They require technological innovations and sophisticated hunting techniques for survival." This research reveals that people inhabited the rainforest far earlier than previously suspected. "Finding an early modern human presence in a rainforest location is remarkable as it suggests that these skills were in place by this time," says Westaway.

Chris Clarkson, who led the Australian research but was not involved with this work, calls the new discovery very timely. "The dating of fossil modern-human teeth from Lida Ajer 73,000 to 63,000 years ago provides the missing link—that is, the first unequivocal evidence of modern human presence in [Southeast Asia] likely just prior to their first appearance in Australia at 70,000 to 60,000 years ago," says Clarkson, an archaeologist at the University of Queensland. "This is a really fantastic result and will renew the search for modern-human sites in Southeast Asia of comparable age, including evidence of their way of life."

See Separate Article: EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Megalithic Sites in Sumatra

Sumatra hosts a number of significant megalithic sites, particularly in the Pasemah Highlands (South Sumatra) with extensive statues and stone structures, and Lampung (Pugung Raharjo) featuring pyramid mounds and dolmens, alongside sites near Lake Toba (North Sumatra) and in West Sumatra (Kerinci Valley), showcasing pre-Hindu-Buddhist cultures with diverse forms like sarcophagi, menhirs, and monumental vases, reflecting ancient social structures and ancestor worship, with some traditions continuing today, especially on nearby Nias Island. [Source: Google AI]

Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine Archaeologist Dominik Bonatz of the Free University of Berlin has conducted research on Sumatra and is building a database of the island’s estimated 1,500 megalithic sites. He has relied in large part on traditional stories to reconstruct the history of sites built from the early seventeenth century until the present. He possesses a uniquely helpful resource: the records of nineteenth-century missionaries who collected information from local people about the sites. Today, he says, people can still recall traditions associated with certain megaliths going back more than 15 generations, noting that their recollections match the stories collected by the missionaries. “They have a remarkably accurate memory of these sites,” says Bonatz. “Monuments constructed three hundred years ago still have very real meaning to them.”[Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2024]

Types of megalithics found in Sumatra include statues of humans and animals,, dolmens, stone chamber graves, menhirs, monumental vases, stepped pyramids, and carved stone sarcophagi. At least some are thought to be linked to ancestor worship, social status, rituals, and military prowess. On Nias there are ones used for stone jumping). Megalithics are difficult to date but it is estimated the ones in Sumatra ranges from 1st millennium B.C. to the A.D. 14th century, with later traditions on Nias and Lake Toba.

Key Megalithic Regions & Sites: 1) Pasemah Highlands (South Sumatra), a A major hub with over a thousand megalithic remains (statues, mortars, tetraliths) from around 2000-1000 B.C., showing pre-Hindu-Buddhist life; 2) Pugung Raharjo (Lampung), an archaeological park with stepped pyramids, menhirs, dolmens, and prehistoric artifacts, showing continuous use from 2500 B.C. onward; 3) Lake Toba Area (North Sumatra), with Batak megaliths, including stone sarcophagi (like those in Tomok) for ancestors, with some still in use today; 4) Nias Island , known for elaborate sculpted megaliths and stone monuments erected for important figures, with warrior traditions like the fahombo (stone jumping); and 5) Kerinci Valley and West Sumatra , containing megalithic buildings like stone chamber graves and monumental vases.

Early History of Sumatra

Much of Sumatra has traditionally been historically, culturally and economically linked to the Malay peninsula not Java. Sumatra was a source of cloves, camphor and sandalwood in ancient times. Sumatra is believed to have been the site Sinbad’s run in with cannibals. Marco Polo stopped in Belawan, Sumatra on his sea journey from China to Venice in 1291-95. The name Sumatra is derived from 12th century port of Sumudra. Sumudra means “ocean” in Sankrit

The remains of the first people in Sumatra date back to 13,000 years ago. The remains appear to have come from hunter-gatherers who lived along the north coast of Sumatra on the Melaka Straight across from now a day Malaysia. There has not been any significant discovery of human remains in the rest of Sumatra up until 2000 years ago when people settled in the Western Sumatra highlands. The first Kingdom to control all of Sumatra was in the 7th Century when the Kingdom of Srivijaya took power. The Kingdom was based close to current day Palembang. The Kingdom took control of the Straits of Melaka, which at the time, was a major trade route between India and China. [Source: sumatra-indonesia.com]

Recorded accounts of Sumatra date back to the period of trade by Baghdad merchants with India and China, by way of Southeast Asia. Suleyman (A.D. 851) first wrote about the island and described it as containing “an abundance of gold. The inhabitants live off the fruit of the coconut tree, from which they make palm wine, and cover their bodies with coconut oil. When someone wants to get married, he must bring the head of an enemy. If he has killed two enemies, he may take two wives. If he has killed fifty enemies, he may take fifty wives.” Other early accounts of Sumatra include “The Book of Indian Wonders” (“Kitab adaib al-Hind”), dated to the year 950; the writings of the famous geographer Edrisi (1154); a description of cannibals inhabiting the island by Kazwini (1203 — 1283); accounts by Rasid Ad-Din (1310); and descriptions of a large island city by Ibn Al-Wardi (1340). [Source: Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia”, Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171]

During the 11th Century, Srivijaya controlled a large part of South East Asia including the Malay Peninsula, Southern Thailand and Cambodia. In 1025 the Srivijaya were conquered by King Ravendra Choladewa from Southern India and Srivijaya soon after that was under the control of the Kingdown of Malayu. In 1278 Sumatra was taken control by the Javanese. The Sumatran power houses relocated their positions to the northern most point of Sumatra - current day Aceh. At this time a lot of Sumatrans were animist. They began trading with the Muslim traders of West India (Gujarat) and soon adopted their religion. These traders were the first to give Sumatra it's name. Soon Islamic Sultanates were setup around the northern region and given control of the sea ports servicing the Straits of Melaka. [Source: sumatra-indonesia.com]

After the Portuguese occupied Melaka, Aceh became the primary power base in Sumatra. The Aceh sultanate eventually claimed most of northern Sumatra and some regions of the Malay peninsula too. The Aceh remained the dominant power n the region until the 17th century when the Dutch began making its first moves into the region. The Dutch based themselves in the western port of Padang and didn’t venture far from there until the 19th century when they launched a serious effort to take over the whole island and were able to claim most of Sumatra with the exception of the Aceh region in the 1860s.

Later History of Sumatra

The Dutch turned parts of Sumatra into rich agricultural areas with tobacco being one of the important cash crops. There was resistance against the Dutch. It wasn't uncommon for a Sumatran villagers to burn their own village the ground and move somewhere else to prevent the Dutch from taking their village. During World War II, the Japanese occupied Indonesia, including Sumatra, from 1942 to 1945. There are caves close to Bukkittinggi that were built by the occupying Japanese army as well as some remains of Japanese bunkers on Pulah Weh off the coast of Banda Aceh in the north.

Indonesia gained independence after Japan's surrender to the United States., but it required four years of intermittent negotiations, recurring hostilities, and UN mediation before the Netherlands agreed to relinquish its colony. Sumatra experienced it share of violence during the struggle for independence and afterwards.The capital of Sumatra, Medan means battlefield. Large numbers of people from Java and China were brought in to work on this plantation as well as others that sprung up after it was discovered that tobacco grew so well here. Over 300,000 Chinese were brought to Medan between 1870 and 1930.

One of Sumtara’s greatest achievements within Indonesia is the naming of Bahasa Indonesia as the national language not Javanese. Eric Musa Pilaing wrote in the Jakarta Post, “We Sumatrans won the language war back in 1928 when the Javanese, the largest cultural group in what is now Indonesia, agreed to use Malay as the root for Bahasa Indonesia, the national language. That's a huge concession on their part that no amount of "Javanization" of our local cultures can ever match...“My sorry excuse for not wearing batik is that to me it is just another form of Javanese cultural domination that we other ethnic groups in Indonesia have had to endure. They already dominate the nation through the sheer size of their numbers, especially among the ruling elite. Their culture permeates our lives, and batik is just another part of this.” [Source: Eric Musa Pilaing, Jakarta Post, November 23, 2008]

Travel in Sumatra

Most foreign visitors arrive by in Medan by plan from Singapore, Kuala Lumpur or Penang r by high speed catamaran from, Penang. Most of northern Sumatra’s attractions are accessible form Medan. Another strategy is tale a boat from Singapore to Batam in the Riau Islands and then fly from Batam on a cheap flight to Medan. Medan and the other cities. Sumatra are well connected to the rest of Indonesia by Indonesia’s legion of upstart airlines.

Travelers to Sumatra usually spend the bulk of their time in northern Sumatra and speed through southern Sumatra or skip it all together on their way to Java or do the same thing in reverse. Most travelers to Sumatra follow the same route, generally starting in Medan and stopping in Bukit Lawang, Berastagi, Danai Toba, Nias, Bukittinggi, Penang and then Java.

These days travelers generally traverse the short distanced by bus and the long distance by plane. There are cheap flights between most of Sumatra’s cities and travel is much easier than the old days when some people took buses that took three weeks to traverse Sumatra in the wet season when travel was slowed by flooded rivers and massive potholes and ruts.. Bus travel is better than it sed yo be but there are sill some bone-rattingly-nasty sections of road. The main higwaus os the Trans-Sumatran Highway which traverse the lenth of Sumatra from orth to south

Volcanoes on Sumatra

Situated in Indonesia's Ring of Fire, Sumatra is home to numerous active volcanoes. Volcanic activity on Sumatra is driven by its position along the Sunda Arc, where the Indo-Australian Plate subducts beneath the Eurasian Plate. This process fuels frequent eruptions and creates serious hazards, including ash clouds that disrupt air travel, pyroclastic flows, and lahars. At the same time, volcanism brings benefits: fertile soils that support intensive agriculture, geothermal activity that produces hot springs, and mineral resources such as sulfur used in traditional practices.

Many of Sumatra’s volcanoes have become important sites for tourism and adventure hiking, offering exceptional biodiversity and unique landscapes. However, because activity levels can change rapidly, especially at highly active peaks like Marapi and Sinabung, visitors are advised to follow official restrictions, use local guides, and respect safety warnings to reduce risk.

Major Volcanoes in Sumatra

Marapi (Gunung Marapi, near Bukittinggi) is one of the most active volcanoes of Sumatra, with frequent gas and ash emissions, but is popular with hikers despite its dangers.

Kerinci (Gunung Kerinci) is Sumatra's highest peak. It is a stratovolcano offering challenging treks with unique flora and stunning views.

Sinabung (Gunung Sinabung in North Sumatra) is known for its significant eruptions and pyroclastic flows, impacting the surrounding areas significantly.

Sibayak (Gunung Sibayak, near Berastagi) is an accessible active volcano featuring hot springs and easy hikes.

Toba (Lake Toba) is a massive caldera from a super-eruption 74,000 years ago, creating the world's largest volcanic lake.

Tandikat and Talang are notable stratovolcanoes in West Sumatra with histories of eruptions.

See Separate Article: VOLCANOES IN SUMATRA factsanddetails.com

Strait of Malacca

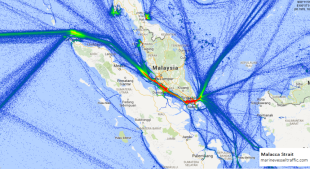

The Strait of Malacca is a narrow strait of water that divides the Indonesian island of Sumatra from Malaysia and Singapore. It is also one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. The 890-kilometer-long waterway carries one third of the world’s trade and one half of the world’s oil supply. Carrying more ships everyday than the Panama and Suez Canals combined, its strategic importance can not be underestimated. The strait doesn't lie in international waters but is located in the territorial waters of Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore and these countries are responsible for patrolling it.

More than 60,000 ships — equal to half the world's merchant fleet — carrying half the world's oil and 40 percent of its commerce pass through the Malacca Strait. The ship range from mammoth supertankers as large as city skyscrapers to tugs and barges. Lots of tankers going between the Persian Gulf and East Asia pass through the strait. As parts of the strait are only one kilometer wide ships have to sail at low speed.

Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: For centuries, this sliver of ocean has captivated seamen, offering the most direct route between India and China, along with a bounty of resources, including spices, rubber, mahogany, and tin. But it is a watery kingdom unto itself, harboring hundreds of rivers that feed into the channel, miles of swampy shoreline, and a vast constellation of tiny islands, reefs, and shoals. Its early inhabitants learned to lead amphibian lives, building their villages over water and devising specialized boats for fishing, trading, and warfare. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic, October 2007]

Patrick Winn wrote in Global Post, “The Strait of Malacca is a natural paradise for seafaring bandits. Imagine an aquatic highway flowing between two marshy coasts. One shoreline belongs to Malaysia, the other to Indonesia. Each offers a maze of jungly hideaways: inlets and coves that favor pirates’ stealth vessels over slow, hulking ships. It's a narrow route running 550 miles, roughly the distance between Miami and Jamaica. This bottleneck is plied by one-third of the world's shipping trade. That's 50,000 ships per year — ferrying everything from iPads to Reeboks to half the planet's oil exports. Avoiding pirates by traveling fast is “practically impossible in the Strait of Malacca. The channel is simply too crowded and too shallow. Gigantic vessels are instead forced to churn through at slow speeds that invite pirates in fast-moving skiffs. (To save fuel, today's cargo ships often travel at about 14 miles per hour. That's slower than 19th-century sail boats.) [Source: Patrick Winn, GlobalPost, March 27, 2014]

History of the Strait of Malacca

At least since the A.D. 1st century, islands in the straits of Malacca, were used as holding area for Indian and Chinese trading ships to find shelter and wait out typhoons that raged in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. Marco Polo briefly described his passage through the strait and a stop at what is thought to be present-day Bintan island. Beginning in the 16th century, Europeans — first the Portuguese, then Dutch and the British — arrived in the area and, realizing the strait’s importance, fought each other and the local sultanates as well as the Malay and Bugis mariners in these waters for control over the strategic shipping channel.

In the 18th century the Strait of Malacca was part of the Malay Peninsula and ruled by the Johor-Riau Sultanate, whose seat alternated between Johor — in present day Malaysia - and Bintan Island, in present day Indonesia. In 1884 the British and the Dutch closed their differences over the strait, its islands and land on either side of it with the signing of the Treaty of London, by which all territories north of Singapore were given suzerainity to the British, while territories south of Singapore were ceded to Dutch powers.

After that Singapore grew and prospered, while the areas the control of the Dutch, who concentrated their efforts in present-day Jakarta and Java, neglected the area. In recent decades, cordial relations between Indonesia and Singapore have led to development on the Indonesian side of the strait, particularly in the Riau islands, where a Free Trade Zone was set up on the Batam, Bintan and Karimun islands.

Piracy in the Strait of Malacca

The Strait of Malacca has been plagued by piracy for centuries. Early sea raiders used fast boats to attack merchant ships, retreating to fortified river settlements and using their plunder to build powerful coastal sultanates in Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. Sailors’ accounts describe extreme brutality, reinforcing the strait’s fearsome reputation. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic, October 2007; John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, November 13, 2006]

Although European colonial powers suppressed these sultanates in the late nineteenth century, piracy never disappeared. In modern times it has taken new forms, including shipboard robberies, organized vessel hijackings, and kidnappings for ransom. Between 2001 and 2007, the International Maritime Bureau recorded hundreds of attacks in the strait, making it one of the world’s leading piracy hotspots.

By 2005, frequent attacks prompted Lloyd’s of London to classify the waterway as a war-risk zone and raise insurance premiums, a designation later lifted after coordinated patrols by Indonesia and Singapore reduced incidents. The strait’s narrow, island-studded geography—combined with political complexities between bordering states—continues to make it difficult to secure. While piracy off Somalia has declined, concerns persist about renewed piracy and even terrorism in the Malacca Strait, a vital chokepoint for global energy and trade flows, as reported by Reuters.

See Separate Article: PIRATES IN THE STRAIT OF MALACCA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Indonesia Tourism website ( indonesia.travel ), Indonesia government websites, UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Japan News, Yomiuri Shimbun, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated in December 2025