MENTAWAI

The Mentawai live on the Mentawai Islands off the west coast of Sumatra. Also known as the Mantawai, Mentawei, Mentawi, Mentawaians, Mentawaier, Orang Mantawei, and Poggy-Islanders, they live a semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle in the coastal and rainforest environments and are one of the oldest tribes in Indonesia and are known for their spirituality, body art (tattoos) , and their practice of sharpening their teeth, which is tied to Mentawai beauty ideals. According to Joshua Project the Mentawai, Siberut population in the early 2020s was 82,000. In 1966, there were 20,000 of them.

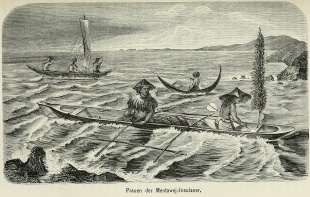

The Mentawai (Mentawei) Islands include Siberut, Sipura, North Pagai, and Utara Selatan and the islands of Nias and Enggano. Although theyare not that far from the Sumatran mainland tricky currents, strong winds and coral reefs have made movement between the two bodies of land difficult and the Mentawai remained largely isolated from the outside world until well into the 20th century. They had their own language and customs and were skilled boat builders but had no crafts. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

The Mentawai Archipelago is part of a chain of non-volcanic islands that runs parallel to Sumatra, about 140 kilometers (85 miles) off its west coast. There are four large, inhabited islands in the group: Siberut, Sipora, and North and South Pagai. The islands have a total area of 6,746 square kilometers (2,605 square miles). Until recently, the islands were covered with dense tropical rainforest but deforestation has greatly reduced the forest cover. The landscape is hilly and dotted with wide valleys.

The name "Mentawai," which was not originally used by the people themselves, is probably derived from the word for "man" — “simanteu”. On Siberut, people identify themselves by the names of the rivers where they live. "Siberut" stems from the name of a local group in the southern part of the island who call themselves "Sabirut," meaning "rats." The inhabitants of Sipora, from the word "pora" meaning "ground," call themselves "Sakalelegat," from "lelegat" meaning "place." Those from the Pagai Islands call themselves "Sakalagan," from "lagai" meaning "village." [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MENTAWAI RELIGION CHRISTIANITY, SPIRITS, SHAMAN factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI LIFE: HOUSING, FOOD, HUNTING, MODERNIZATION factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI TATTOOS factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI ISLANDS: RAIN FORESTS, SURFING, UNIQUE TRIBES factsanddetails.com

Mentawai Language

The Mentawai Language belongs to the Austronesian language family as do most the languages in Indonesia. It is spoken in the Mentawai Islands Regency in the West Sumatra Province. Monganpoula Village in the North Siberut District, Maileppet Village in the South Siberut District, Sioban Village in the Sipora District and Makalo Village in the South Pagai District. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999; Wikipedia]

The Mentawai language consists of three dialects: 1) North Siberut, 2) South Siberut, and 3) Sipora Pagai. The North Siberut dialect is spoken in Monganpoula Village in the North Siberut District. The South Siberut dialect is spoken in Maileppet Village in the South Siberut District. The Sipora-Pagai dialect is spoken in Sioban Village in the Sipora District and in Makalo Village in the South Pagai District. It is the standard dialect because it has the widest geographical distribution and the largest number of speakers. It is also located in the district government center.

Based on dialectometric calculations, the percentage difference between the three dialects ranges from 51 to 69 percent. The Mentawai isolect is a language with a percentage difference ranging from 81 to 100 percent compared to Batak and Minangkabau. According to Pampus (1989), the Mentawai people on Siberut speak several substantially different dialects. However, the southern Siberut dialect is closely related to the dialects of Sipora and Pagai. All of the dialects differ greatly from the most closely related Western Austronesian languages, such as those spoken by the Toba Batak and Niasans.

Early History of the Mentawai

The ancestors of the Mentawai are believed to have migrated to the Indonesian archipelago between roughly 2000 and 500 B.C.. as part of the wider movement of Austronesian-speaking peoples into Island Southeast Asia. They belong to the Proto-Malay cultural tradition and speak an Austronesian language. Linguistic and cultural evidence suggests long internal migration within the archipelago itself: the peoples of Sipora and the Pagai Islands are generally understood to have originated from southern Siberut, from which they separated in a relatively recent period. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999; [Source: Lars Krutak, Tattoo anthropologist; Wikipedia]

Mentawai culture reflects a Neolithic heritage, with only limited influence from later metal-age traditions. On Siberut alone, at least eleven distinct cultural areas can be identified, the most linguistically distinctive being Simalegi in the island’s northwest. Despite these internal differences, Mentawai societies across the islands share closely related cultural patterns.

One theory links Mentawai ancestry to early migrations from Yunnan in southern China, with later interaction with Dong Son–era cultures in mainland Southeast Asia. While many related groups continued eastward into the Pacific, others settled along the western fringe of Sumatra, becoming the ancestors of present-day Mentawai clans. The Mentawai themselves preserve no oral tradition of distant origins.

Mentawai Taboos and Ritualized Combat

Lars Krutak wrote: The Mentawai have developed an elaborate system of taboos that govern everything they do. For example, they live in harmony with nature by taking only what they need; they only eat fruit when it is season, and they only eat meat during ceremonial occasions. At all other times of the year, they eat their staple food sago which comes from the sago palm, various types of greens, and rice.... Before a hunt, men cannot wash their hair or else they will shoot their arrows poorly or they will become sick. When making arrow poison, men are forbidden to sleep or bathe that night. If they do, the monkeys they hunt will die high in the trees, or the poison will become diluted and ineffective. During the hunt itself, hunters cannot strike their dogs; because if they do, it is believed that they will not catch any game[Source: Lars Krutak, Tattoo anthropologist]

Headhunting was practiced by some Mentawai groups in the past. Traditionally, before open hostilities broke out between uma, a system of institutionalized rivalries (pako) allowed time for tensions to cool. These rivalries involved extraordinary prestations that were publicly announced in the valley. Their purpose was to humiliate the opponent, though over time they often became burdensome for both sides. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999]

The traditional knife of the Mentawai people is called a Palitai, and their traditional shield is called a Kurabit. Conflicts rarely involved open combat. Instead, they tended to drag on for long periods, marked by occasional ambush attacks. When the opposing parties agreed to make peace—sometimes at the urging of a third, mediating group—losses on both sides were balanced through ritualized exchanges. Until the early colonial period, Siberut maintained a ritualized form of armed conflict in the practice of headhunting (mulakkeu), which was directed at specific regions outside one’s own valley. This custom was sacrificial in nature and was primarily associated with the consecration of a new uma. On the southern islands, however, headhunting had already been abandoned several generations earlier.

Later History of the Mentawai

European awareness of the Mentawai dates to the late eighteenth century, with the first substantial written account appearing in 1799. During the nineteenth century, colonial officials produced a growing body of reports, reflecting the strategic importance of the islands. In 1821, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles remarked admiringly on the Mentawai, describing them as “even more admirable and probably much less spoiled” than other island peoples he had encountered. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999; [Source: Lars Krutak, Tattoo anthropologist; Wikipedia]

Dutch colonial administration and Protestant mission activity began in earnest in the early twentieth century, later joined by Catholic missions. Certain practices—such as headhunting and extended ritual feasting—were banned, and a modest poll tax was introduced, but colonial interference in everyday life remained limited. This situation changed dramatically after Indonesian independence in 1950.

Today, most Mentawai live in government-controlled villages, practice Christianity, and reside in simple single-family houses with access to schools and churches. Yet on Siberut, fragments of the traditional cultural system continue to survive, sustained by communities that have managed, against considerable odds, to remain rooted in the forest landscape that has shaped Mentawai life for millennia.

Oppression of the Mentawai

The post-independence government of Indonesia launched aggressive modernization campaigns, particularly on Siberut. Indigenous religious practices were outlawed, and all Mentawai were required to adopt either Christianity or Islam. Traditional customs such as tattooing, tooth filing, the wearing of loincloths, and shamanic rituals were condemned as “pagan” or “backward.” Four administrative districts (kecamatan) were established, two on Siberut and two on the southern islands, accelerating state control.

By the 1990s, repression intensified. Many Mentawai were forcibly relocated from forest settlements to government-built villages. Shamanism was effectively criminalized, and police confiscated sacred objects, ritual attire, and medicine bundles from sikerei (shamans), often humiliating them publicly. Anthropologist Lars Krutak documented some of these actions. He wrote: Police stripped practicing shamans (sikerei) of their medicine bundles, sacred objects, loincloths, and their long hair. Sadly, Mentawai shamans, the keepers of the rain forest and their peoples, were denied their basic human rights; even when these abuses occurred under the noses of international organizations like UNESCO, the World Wildlife Fund, and Friends of the Earth, who were more concerned about saving Siberut’s primates than their indigenous peoples!

Despite these pressures, some Mentawai groups in the remote interior of Siberut successfully resisted relocation and cultural suppression. One such group, the Sarereket (“people of this place”), chose to abandon their ancestral village of Ugai and move deeper into the rainforest to preserve their traditional way of life. Since the mid-1980s, limited recognition of Mentawai culture—partly through ethno-tourism—has helped some interior communities maintain greater autonomy.

Mentawai Society

Traditional Mentawai society was organized around patrilineal clans, clan communities, and central clan houses (uma). People lived in tribal groups, each usually occupying its own village (langgai), typically located along rivers. Over time, villages came to include two groups: the original village founders (si bakat langgai) and later arrivals (si toi). The founding group held special rights, especially over land and food resources, and immigrant families had to seek permission from the clan leader to clear fields or build houses. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999; Wikipedia]

An uma usually housed 5–10 nuclear families, and sometimes as many as 20. Membership was based on descent through the male line, making the uma a patrilineal extended family. A patrilineal descent group was known as a muntogat, each with its own uma name that served as a shared family name and a focus of social life. Among the Mentawai, clan names are called suku, as among the Minangkabau, and are used as surnames. More than fifty such clans are known.

Mentawai uma communities had no formal leadership and were based on strong ideals of equality and mutual support. All members were expected to help one another, and decisions were made through open discussions among adult members. If serious conflicts could not be resolved, the community might split. Women attended discussions but had less influence in public matters, though they carried more weight in family affairs.

There was no political organization above the uma, and each group managed its own relations with others. While peaceful coexistence was the stated ideal, competition for prestige often created tension. Exogamous marriage, cooperation between uma, and formal friendships helped reduce conflict. Without leaders to enforce rules, antisocial individuals were dealt with through social avoidance and belief in religious sanctions rather than coercion.

Mentawai Clans and Kinship

Clan members were linked primarily by shared descent myths. In the past, contact between uma in distant valleys was limited, and headhunting expeditions could even result in the accidental killing of a clan member from another area. Despite the importance of clans, the uma remained the core unit of daily life. On Siberut, an uma included married men descended from a common male ancestor, their wives, unmarried daughters, and widowed sisters who had returned to their natal group. It could also include adopted immigrant families (nappit), who were treated as full members with equal rights and obligations. On Sipora and Pagai, uma membership was also patrilineal in principle, though members of different clans often lived together in a single uma. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999; Wikipedia]

Mentawai kinship terms were flexible and designed to emphasize social closeness rather than strict genealogy. When no specific relationship was involved, relatives were treated like siblings, and the terms used for children depended largely on the speaker’s gender. More precise relationships could be marked with special prefixes. Marriage relations showed asymmetry, particularly between brothers-in-law, reflecting non-prescriptive exogamy rules. In everyday speech, kinship terms were often used to create intimacy even among non-relatives, such as referring to one’s wife or children through shared kin categories rather than possessive terms.

The Mentawai kinship system was of the Dakota type, in which kinship formed the central organizing principle of social life. Extended families, rather than nuclear families, were the core social units, and being a good relative was a key moral value. The terminology reflected a patrilineal ideology; on the southern islands, for example, the term for “father” (ukkui) also referred to an ancestral spirit on Siberut, underscoring the close link between descent, kinship, and ancestor worship.

Mentawai Families

Daily life centered on nuclear families living and working separately in their gardens, while ritual life emphasized communal living in the uma. Daughters left their natal uma at marriage but returned if divorced or widowed. Adoption was common, both permanent adoption of adults and temporary adoption of children to strengthen ties between families. When an uma grew too large, it split, with adopted or more distant branches usually moving away. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999]

Children learned through observation rather than formal education. Their growth was marked by ceremonies, but there was no single initiation rite. Toward the end of puberty, teeth were filed and tattoos applied in stages. From then on, young men began establishing their own fields and livestock, while young women prepared for marriage, knowing that most of their work and tools would remain behind when they joined their husband’s uma.

On Siberut, inheritance mainly followed the male line, with sons receiving equal shares. Daughters could inherit certain movable goods, especially items acquired during marriage or made by their mother, but these passed back to their brothers after the daughter’s death, returning the property to the patrilineage. North and South Pagai differed somewhat because taro, the staple crop there, was grown by women. Taro fields were said to be inherited through women, but this was not permanent: when a brother married, his sister transferred part of her fields to her sister-in-law, effectively returning the land to the patrilineal line.

Mentawai Marriage and Sex

Marriage was monogamous, and divorce was uncommon. In principle, marriage was exogamous at the clan level, but in practice this rule applied mainly to the uma. Certain close relatives—such as a mother’s brother’s daughter and cross-cousins—were considered too closely related for marriage. There were no preferred marriage partners, and marital ties were spread across many uma within a single generation. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999]

Bridewealth, which could include fruit trees, taro fields, pigs, and tools, was contributed collectively by wealthy men of the groom’s uma, while the bride’s side returned gifts of pork. On the southern islands, bridewealth had already disappeared before the colonial period. A married woman joined her husband’s uma, and a husband was subordinate to his brothers-in-law, assisting them in ritual matters. In cases of “child exchange,” this relationship could be reversed. Unlike on Siberut, the southern islands allowed marriage within the same uma as long as the partners belonged to different patrilineages.

Premarital relationships were treated as private matters. Lars Krutak wrote: In the traditional longhouse or uma of the Mentawai people, sex is taboo. If you want to “get busy,” you and your companion must head out to the jungle and use one of the “love shacks” that dot the landscape.”

Practices also differed between Siberut and the southern islands in premarital relations and fatherhood taboos. On Siberut, men with young children were forbidden to carry out activities believed to cause plants to wilt, including planting. On the southern islands this taboo applied to all married men, leading couples to delay formal marriage until their thirties or forties. Before marriage, couples lived in separate huts (rusuk) near the village, spending nights together but returning to their parents’ homes by day. These unions were publicly recognized and expected to be stable. Children born during this period were raised in the household of the mother’s father, and only later, after formal marriage, were incorporated into the father’s patrilineage.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025