MENTAWAI RELIGION

Most Mentawai are Christians. According to Joshua Project about 80 percent of Mentawai are Christian, with five to ten percent of these being Evangelicals. Widespread conversion to Christianity, beginning in the 1950s, has led to disappearance or at least minimization of many traditional cultural practices. Some are Muslims. The Mentawai Protestant Christian Church (GKPM) was founded in 1916, and has unique Mentawai infusions and and a congregation of approximately 35,000 people.

The Mentawai follow a belief system called Arat Sabulungan, which is an animist religion that links the supernatural powers of ancestral spirits to the ecology of the rainforest. If the spirits are mistreated or forgotten, they may bring bad luck, such as illness, and haunt those who forgot them. The Mentawai people also have a strong belief in holy objects. In their traditional religion they worshiped spirits with the spirits of the jungle, sky, rivers and the earth being the most important. Sickness was viewed as the soul leaving the body temporarily and death was when the soul left the body for good. When death occurs the soul becomes a ghost and certain taboos are observed to prevent these ghost from stealing people’s souls. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); Wikipedia]

In the Mentawai tradition religion, everything that exists is believed to have its own soul (simagere; comparable to the Malay semangat, and after death ketsat). This includes humans, animals, plants, and even objects. Objects are not seen as lifeless things to be used freely but as beings that must consent to their use. Before killing a pig, for example, people explain and apologize to it, often making offerings. Objects also expect people to respect their nature. This belief explains the many taboos connected to daily activities. A man, for instance, should not carve a dugout canoe while his wife is pregnant. Hollowing out a tree is considered incompatible with a time focused on avoiding “emptiness,” meaning the need to carry a child safely to full term. Ignoring this taboo may anger the spirit of the tree, causing illness, a failed canoe, or even miscarriage.[Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999]

The human soul itself is another source of danger. It can leave the body and wander freely, and its journeys form dreams. If life becomes unpleasant, the soul may choose not to return and instead join the ancestors. To prevent this, Mentawai people try to make life appealing to the soul by providing good food, avoiding excessive stress, and maintaining physical beauty through tattoos, ornaments, and decorations.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MENTAWAI: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, SOCIETY, FAMILIES factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI LIFE: HOUSING, FOOD, HUNTING, MODERNIZATION factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI TATTOOS factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI ISLANDS: RAIN FORESTS, SURFING, UNIQUE TRIBES factsanddetails.com

Mentawai Spirits

There are no supreme gods in Mentawai belief. Instead, many kinds of spirits—saukkui, sanitu, and sabulungan—are believed to live everywhere: in forests, rivers, the sea, the sky, and beneath the earth. Some spirits are harmful and must be avoided, while others are friendly to humans. Because spirits are invisible, everyday actions can disturb them unintentionally. Cutting down a tree, for example, may damage a spirit’s dwelling. The spirit’s bajou—a force or radiation that comes from all beings with souls—can then affect the person responsible and cause illness. For this reason, ceremonies are performed before major activities to calm and please the spirits. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999]

Some spirits are closely linked to the uma (longhouse). According to myth, the first uma was founded by an orphan boy who learned secret knowledge from a water spirit in the form of a crocodile. After conflicts with a companion, the boy moved underground and became one of the spirits of the interior. He is now associated with earthquakes and fruit trees and still receives sacrifices during major rituals. The crocodile spirit continues to protect the uma. If someone behaves selfishly—such as secretly eating meat—this offends the crocodile spirit, who may enter the uma and make the offender sick.

Lars Krutak wrote: For the Mentawai, the jungle has always been a place where everything, from plants to rocks to animals and man, has a spirit (kina). Spirits are believed to live everywhere and in everything – under the earth, in the sky, in the water, in the treetops, in bamboo, in a dugout canoe – and they are spoken too because they speak and act as human beings do. Some spirits offer protection and help to humankind. But others are evil and hand out punishment in the form of sickness and disease. In the malaria infested jungles of Siberut, there is no doubt that human existence is constantly threatened by disease. For this reason, the population density has always been low. The Mentawais attempt to explain the onslaught of illness as not living in harmony with oneself and the environment. To maintain this harmony, religious and everyday codes of conduct must be followed at all times because acting recklessly or breaking taboo will anger the spirits of disease that live in the jungle. [Source: Lars Krutak, Tattoo anthropologist +++]

Pagete Sabbau or Teteu (“Grandfather”) is the Mentawai’s most revered spiritual figure. “According to myth, Pagete Sabbau was the first Mentawai shaman and taught his people everything they know today – including tattooing. But the people became jealous of him because of his magic and determined to kill him. When they built their first uma they sent Teteu down to dig under the center post. Then they let the post down on his head, imprisoning him in the ground. In revenge,Teteu knocked the uma down with an earthquake. +++

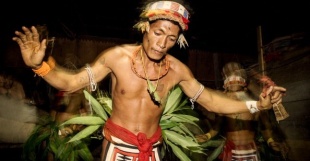

To fend off disasters, “the Mentawai people began to offer human sacrifices to their Grandfather. Traditionally, these were made under the center pole of a new uma upon its construction. Although these types of sacrifices are no longer practiced, today it is taboo to let blood drop to the ground for fear of earthquakes. So when chickens or pigs are sacrificed, their necks are wrung or their bodies are speared so that they bleed to death internally. Pagete Sabbau is so revered today, that it is taboo to mention his name unless in the most serious of conversations. Aman Lau Lau is very hesitant to speak about him, because his power is so great. And the only time Teteu is summoned these days is when a new uma is built; because Teteu is pleased by the beautiful dancing that takes place in his honor. +++

Mentawai Shaman

On ritual occasions, an experienced elderly man serves as the master of ceremonies, or Rimata. In some ceremonies, he represents the other adult men. In others, however, all adults perform corresponding tasks collectively. Shamans (sikerei or kerei) have additional ritual responsibilities besides their healing duties. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999]

Lars Krutak wrote: “Aman Lao Lao is a Mentawai sikerei, literally “one who has magic power.” But he is not just a doctor. He is a leader, priest, herbalist, physician, psychologist, dancer, family and community man. Although Mentawai society is egalitarian, shamans are considered to be the leaders of their people. They are the tribe’s connection to the spiritual world, but also to the outside world. Sometimes they travel to distant cities to meet with government officials to fight for their human and environmental rights. +++ [Source: Lars Krutak, Tattoo anthropologist +++]

“Aman Toshi, who is approximately 80-years-old, is completely tattooed and is the oldest shaman residing in Butui. All Mentawai shamans, like Toshi, must be tattooed so that they are more beautiful to the spirits with whom they communicate on a daily basis. Of course, it is easy to spot a Mentawai shaman because only they can wear red loincloths (kabit) made from the bark of the baiko tree. Barkcloth or tapa as it is known in Polynesia, is found throughout the forests of Indonesia and the islands of the Pacific. When it was dyed red in Polynesia, it almost always indicated that the wearer was nearly divine; a belief that the Mentawai people continue to share.

Aman Telephon is Aman Lau Lau’s second oldest son and recently he became a Mentawai shaman. For days, he vanished alone into the jungle to meet the spirits, because this was an important part of his shamanic training. But before Aman Telephon could become a full-shaman in the eyes of the community and his father, he needed to be tattooed. After a 45-minute tattoo session with Aman Bereta, he passed the final test. The tattoo master finished the job with a ritual cleansing of his wounds with water and medicinal plants: a type of fern and the leaves of an unidentified shrub used to “cool down” the tattoo so as not to aggravate spirits lurking in the vicinity. +++

Mentawai Shaman Duties and Rituals

Lars Krutak wrote: “The religious beliefs of the Mentawai are centered on the importance of coexisting with the invisible spirits that inhabit the world and all the animate and inanimate objects in it. Health is seen as a state of balance or harmony, and for the Mentawais it is something holy and beautiful. But if the balance is broken, the only way to restore it is by placating the spirits that have been offended or accidentally distressed. With the help of medicinal plants, these malevolent spirits can be “cooled down” by magical means, and then they are appeased with sacrifices. The intermediary in these contacts is always the Mentawai shaman, or sikerei, because only he can communicate with the spirits. [Source: Lars Krutak, Tattoo anthropologist +++]

Because the Mentawai belief system is animistic and has many taboos limiting it, it is the responsibility of shamans like Aman Lau Lau to maintain his people’s balance with the natural and spirit worlds. For Aman Lau Lau and the other Mentawai shamans of Butui village, nature is both religion and survival, and they must know the forest inside and out to successfully maintain the balance between these complex worlds. Sickness may be treated with medicinal plants, but it is the intervention of the shaman on the spiritual plane that ultimately determines a patient’s fate. And for this reason, the sikerei must fly away on the wings of trance to work his deeds of magic rescue. +++

“As in other indigenous cultures, the Mentawai believe that all disease is nothing but the loss of the soul (ketsat), and if it abandons the body sickness or death will be the result. Soul-loss is usually attributed to the spirits of disease or of ancestral ghosts (sanitu), and numerous ceremonies are carried out to appease them if taboos have been broken. One of the most important shamanic ceremonies held to mend broken taboos is the pasaksak. Once it begins, all work is taboo except for the necessary cooking and rituals. Though the Mentawais have many pasaksak – for the cutting of trees, the building of canoes and longhouses, weddings, funerals, hunting expeditions, initiations, visiting strangers, healing rituals, and tattooing – all of them are conducted to make amends to the spirits of the jungle and of the ancestors for the breaking of any number of taboos. +++

Mentawai Ceremonies

The main religious festival of the uma is known as Puliaijat on Siberut and Punen on the southern islands. It may last several weeks and can be held more than once a year, especially in response to major events such as weddings, the construction of a new longhouse, or the appearance of bad omens. During the ritual period, everyday work, casual contact with neighbors, and even sexual relations are forbidden. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999]

The ritual is led by the Rimata, assisted by his wife. A central element is the offering of a chicken, called lia, which is used both to attract beneficial forces and to ward off harmful ones. After the chicken is sacrificed to the spirits, its intestines are examined for divination to determine whether the outcome is favorable. This dual purpose—protection and blessing—continues throughout the ritual and reflects a symbolic reordering of social relationships within the uma and with the outside world.

On Siberut, the ritual unfolds in two main phases. In the first, often with the help of shamans from neighboring communities, the emphasis is on driving away evil influences. In the second phase, with the support of the spirits, attention shifts to attracting positive forces, especially the reuniting and strengthening of the souls of the uma’s members. The ritual concludes with the entire community moving for several days to a hunting camp deep in the forest. By doing so, participants deliberately enter the realm of forest spirits. The monkeys hunted there are considered the livestock of these spirits, and by allowing them to be taken, the spirits are believed to grant blessings to humans.

The exact form and duration of Puliaijat or Punen vary according to their specific purpose. Some earlier accounts of the southern islands contain exaggerated claims, such as Loeb’s 1928 suggestion that completing a new uma required at least nine years. While Punen follows the same basic principles as Puliaijat, its ceremonies before the hunting camp place greater emphasis on daily activities, which are ritually renewed step by step.

Mentawai Funerals and Views About Death

When a soul has eaten and adorned itself with the ancestors—called Ukkui on Siberut and Kalimeu on the southern islands—the person must die. On Siberut, death divides the individual into two distinct beings. The soul becomes an ancestral spirit, while what remains of the decaying body and bones is personified as a ghostlike being known as Pitto’. [Source: Reimar Schefold and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September 1999]

The Ukkui, who are direct ancestors, live in an ancestral settlement called Laggai Sabeu. Their existence resembles human life but is more beautiful and free from death. They are the closest spiritual helpers of a community and are invoked on all important occasions to bestow blessings. They play a central role in the second phase of the Puliaijat ritual and are sometimes formally invited to stay in the longhouse for an extended period.

By contrast, the Pitto’ remains near the burial grounds, which are always located far from human settlements. Driven by jealousy, it seeks to enter the uma, where it can cause illness among the living. For this reason, it must be regularly expelled during ritual events.

On the southern islands, attitudes toward death appear to have changed. As on Siberut, a distinction was once made between ancestral souls dwelling in Laggai Sabeu and body-ghosts associated with burial grounds. On Sipora and Pagai, however, ancestral spirits gradually came to be feared rather than trusted or relied upon. As a result, the difference between ancestors and body-ghosts became less clear. In ritual practice, people no longer called directly upon the ancestors for help but instead addressed other categories of spirits. Offerings to the ancestors were made mainly to persuade them to leave the living in peace.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025