BATAK CULTURE

Even though the Batak live in a fairly isolated region their culture has been influenced by outside cultures, notably India. The Batak language originally had its own Sanskrit-derived script but now is largely written with the Latin alphabet. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Batak have a rich oral and written traditional as expressed in verse-form verbal duets, mythic chants, dirges and clan genealogies. Bataks music was traditionally performed at religious ceremonies. The Batak are known throughout Indonesia as good singers. They are particularly famous for their emotional hymn singing. Batak traditional instruments are similar to those elsewhere in Indonesia: copper gongs struck with hammers, reedy wind instruments and a two string violin. ~

The Batak have a reputation for being skilled metal craftsmen. They used to have elaborate rituals, carvings and dances. Masked dances once served as a way of communicating with spirits and ancestors but now they are mostly performed for tourists. “Sahan” (Batak medicine holders made from buffalo horn) used to have a high degree of spiritual meaning. Now are they made mainly to sell to tourists. They are still made with high degree of artistic skill. ~

The human-sized puppets are now used more in marriage celebrations than for funerals. The puppets are carved from the wood of a Banyan tree and is dressed in a traditional costume, red turbans and blue sarongs.. They are placed on wooden boxes and made to dance by puppeteers to gamelan music or flutes and drums. The origin of the art form is not known. According to one story it originated with a lonely widow who made a wooden image of her husband after he died and hired a puppeteer to make him dance and a mystic to communicate with the dead. ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

BATAKS: GROUPS, HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND WERE THEY REALLY CANNIBALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, BURIALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, KINSHIP factsanddetails.com

BATAK LIFE: HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SUMATRA factsanddetails.com

SUMATRA: HISTORY, EARLY HUMANS, GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE factsanddetails.com

LAKE TOBA AREA: BATAKS, SAMOSIR ISLAND AND THE TOBA SUPERVOLCANO ERUPTION 71,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

Batak Literature and Folklore

Batak oral literature includes undung-undung, which are laments for the dead that include fixed expressions which can no longer be understood, as well as tonggo-tonggo, which are poetic prayers recited during offering ceremonies. These include tabas incantations. The Toba Bataks made mystical augury books known as “pustaha” (See Below). Carved from bamboo and bark, they contained important historical records and provided instruction for religious ceremonies and rituals. Other books made from sacred bones and bamboo recorded myths. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Beyond the islands of western Indonesia, whose local scripts all derive from mainland Asian prototypes, the peoples of the Pacific had no written languages, with the sole exception of Rapa Nui {Easter Island), which developed an indigenous symbolic system whose precise nature and meaning remain uncertain. Eric Kjellgren wrote: The Batak are one of only a handful of Pacific and Oceanic peoples who possessed a written language prior to Western contact. Ultimately derived from an Indian prototype, writing was introduced to the region centuries ago through contact with the Hindu kingdoms of Java or Sumatra, or perhaps directly by traders from lndia. Batak cosmology shows evidence of Hindu influences and Batak texts and religious terminology contain numerous words of Sanskrit origin. Batak writing was understood and used solely by male religious specialists, called datu in the Toba Batak language, and was primarily used to record hadatuon, the sacred knowledge and magical formulas required by the datu in performing rituals.[Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

According to the Toba creation myth, the primordial universe consists of the seven-layered upper world of the god Mula Jadi Na Bolon and the watery underworld of the dragon serpent Naga Padoha. Mula Jadi Na Bolon had three sons with a blue hen: Batara Guru, Mangalabulan, and Soripada. He also sired three daughters to give to his sons as wives. Batara Guru's daughter, Si Boru Deak Parujar, created the earth. She married her cousin, Boraspati ni Tano—the lizard-shaped son of Mangalabulan—and gave birth to twins of different sexes. These twins then married each other, descended to the earth at the Pusuk Buhit volcano (on the west shore of Lake Toba), and founded the village of Si Anjur Mulamula. All humanity descends from this pair. One of their grandchildren, Si Raja Batak, is the ancestor of the Batak people (though other Batak groups do not widely recognize this genealogy). ^

Batak Music and Dance

The Batak people are celebrated throughout Indonesia for their love of music. They are often seen performing in hotels and restaurants. Traditional ensembles fall into two categories: one for loud outdoor ceremonial music and the other for quiet indoor music. The former includes the gondang, a set of long, cylindrical, tuned drums beaten in dynamic rhythms; the sarune, a penetrating oboe played with circular breathing; and the ogung, or gongs. The latter includes the hasapi (a long-necked lute), the surdam (a bamboo flute), and the keteng-keteng (a zither made of bamboo tubes and struck with sticks). [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Batak accompany themselves on guitars and, nowadays, Yamaha electric organs as they sing passionate songs (lagu Batak), whose style reflects Portuguese and Spanish influences. This music is widely available on cassette. Churches may have as many as ten choirs singing hymns in unison and improvised four-part harmonies that are no longer known in Europe.

Traditional dances served three main functions: showing respect for guests, especially the host's wife-giving kin group, inducing possession by spirits through orchestral crescendos, and entertaining young people, often with a humorous erotic component. Funerals include the tortor, a solemn dance with slow, rigid movements.

Batak Art and Crafts

The Batak are one of the largest indigenous populations in Indonesia. They live primarily in the mountainous highlands of northern Sumatra and are divided into six main groups: Toba, Pakpak/Dairi, Karo, Angkola, Mandailing, and Simalungun. The Batak work in virtually every medium, producing an enormous diversity of art forms, from monumental wood and stone sculptures to delicately carved ritual objects, metalwork, and textiles.' [Source: “Emily Caglayan, Ph.D., Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Batak villages and regions traditionally specialize in particular crafts, including textile weaving; mat and basket making; iron, gold, and silver working; pottery; and woodcarving, which plays an especially important role in decorating traditional houses. Traditional Batak communal houses are conceived as three-tiered structures reflecting the three levels of the universe: the upper world, middle world, and lower world. The high, soaring roof symbolizes the upper world, the realm of the gods. The living area, raised on wooden pillars, represents the middle world inhabited by humans. Beneath it is a space for animals, corresponding to the lower world, believed to be the dwelling place of a mythological dragon. Prominent decorative features include large carved animal heads positioned at the ends of side beams; these sculptures are thought to release beneficial energy and protect inhabitants from illness and malevolent forces.

The Toba Batak, who occupy the central part of the Batak region, are especially renowned for their handwoven textiles. Produced exclusively by women, these cloths serve both as clothing and as ritual gifts exchanged to mark social relationships. One important textile, the ulos ragidup, plays a central role in wedding ceremonies: on the wedding day, the bride’s father presents it to the groom’s mother, symbolizing the union of the two families and the hoped-for fertility of the couple. The cloth is then preserved as an heirloom and passed down through generations.

The Toba Batak are also known for carved wooden puppets called si galegale. These figures are used in funerary ceremonies for wealthy men who die without male heirs to perform their mortuary rites. Carved to resemble the deceased, dressed in clothing, and animated by a system of internal strings, the puppet dances among the mourners. At the conclusion of the ceremony, it is stripped of its clothing and cast over the village walls, marking the final release of the dead from the community.

Datu

Among the most powerful figures in Batak communities have been ritual specialists known as datu. Usually drawn from the village’s founding lineage and exclusively male, datu were experts in religious knowledge. They were believed to cure illness, communicate with the spirits of the dead, and determine auspicious days for rituals and major events. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Datu acted as intermediaries between the human and spiritual worlds. Much of Toba Batak sacred art centered on the creation and adornment of objects that would be used by the datu for divination, curing ceremonies, malevolent magic, and other rituals. Among the most important were ceremonial staffs, books of ritual knowledge known as pustaha and a variety of containers used to hold magical substances, such as this perminangken.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Datu were second in rank only to the village headman. They performed both benign and malevolent magic using a variety of ritual paraphernalia. These objects were primarily used to hold pukpuk, the most potent supernatural substance in the datu's magical arsenal, which was most commonly derived from the body of a ritually slain human victim whose captured spirit (pangulubalang) served the datu as a supernatural helper. However, the instructions for preparing pukpuk recorded in some pushtaha indicate that animals rather than humans could be used.

Datu’s Ritual Staff

A datu’s most important possession is his ritual staff, carved from special wood and symbolizing the tree of life. Each specialist must create his own staff, resulting in great variation in form and style. The simplest type, known as tungkot malehat (“smooth staff”), bears a single carved wooden or metal figure at its top. The staff’s power is activated by inserting a potent magical substance called pupuk, which is kept only in specific containers such as hollow water-buffalo horns, wooden vessels, or imported Chinese ceramics. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Toba Batak itual staff made of wood, fiber and hair. Dated to the 19th or early 20th century, it is 180.3 centimeters (71 inches) long. On the staff is finial (Tungkot malehat) made from copper alloy and resin and measures 11.4 centimeters (4.5 inches).

Datu frequently employed ritual staffs when performing ceremonies. Eric Kjellgren wrote: These staffs were of two types, the larger tunggal panaluan and the smaller, composite staffs known as tungkot malehat. Accounts of the use of tunggal panaluan indicate that the datu entered into a trance and danced and performed rites while holding the staff, whose supernatural powers aided him in curing, divination, benevolent and malevolent magic, and other ritual procedures. 1 The tungkot malehat were likely employed in a similar manner. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Carved from a single piece of wood, the tunggal panaluan depict a sequence of human and zoomorphic figures positioned one atop the other. The two figures at the top depict the legendary twins Si Adji Donda Hatahutan and his sister, Si Tapi Radja Na Uasan, to whose incestuous relationship the origin and imagery of the tunggal panaluan can be traced. According to oral tradition, when the relationship was discovered the sister was sent away. Her brother soon found her and the two fled to the forest, where they encountered a tree known as pio-pio-tang-guhan, hung with ripe fruit. As Si Adji Donda Hatahutan climbed the tree to pick fruit for his sister, he was transformed into a wood image, which merged with the tree. His sister, following after him, met the same fate.

Seeing that the twins had been entrapped, a succession of datu and animals attempted to rescue them. As they climbed, they, too, merged with the tree, below the illfated twins. The supernaturally charged tree was later cut down, becoming the first tunggal panaluan. On one staff the brother, Si Adji Donda Hatahutan, stands proudly atop the staff, his head clad in an elaborate turban surmounted by a plume of hair. His hands rest on his sister's head, and the two figures st and on a mythical elephant-like creature. A series of human figures and fantastic animals appears below, their sinuous bodies contorted into a variety of positions.

In contrast to the tunggal panaluan, the tungkot malehat were composite objects consisting of a shaft of wood or bamboo, often adorned with metal bands or incised with magical designs, surmounted by a separately created finial depicting a single human figure. The identity of the solitary human image, carved from wood or, occasionally, as here, cast from a brasslike alloy of copper, is uncertain. Both tunggal panaluan and tungkot malehat were reportedly made by the datu himself. However, it seems probable that the metal finials of tungkot malehat were produced by artisans who specialized in metal casting.

A masterpiece of Batak metalwork, one staff depicts a seated figure, clad in an elaborately ornamented ftowing headcloth and a band-like necklace, whose delicate hands hold a cylindrical vessel. His serene facial features and enigmatic smile suggest he may be in a trance. This, together with the vessel, which possibly represents a container for magical substances, suggests that the figure portrays a datu in th e course of a ritual performance. The fi gure was created using the lost-wax process. Its delicate features were modeled in a mixture of wax and resin, over a core of clay mixed with rice straw or charcoal. The wax was subsequently melted away, producing a hollow mold into which the molten metal was poured. Cast hollow, this figure was later filled with a dark resinous material that is visible through the headdress and on the chest. This was almost certainly a magical substance whose supernatural powers were intended to permeate the figure and the staff it once crowned, making it a formidable ally to the datu in the performance of his ceremonial duties.

Book of Ritual Knowledge (Pustaha)

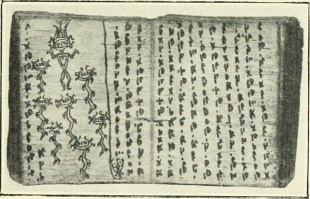

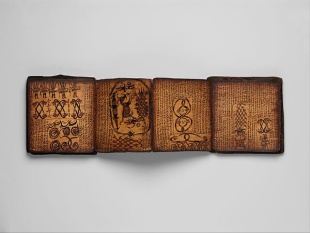

In former times each datu possessed a book, known as a pushtaha, which contained the esoteric religious knowledge and ritual instructions passed down to him by his predecessors. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Toba Batak Book of Ritual Knowledge (Pustaha), made of wood, bast, resin ink and fiber. Dated to the 19th-early 20th century, it measures 20×20×6.4 centimeters (7.88 high, 7.88 inches wide and 2.5 inches (deep). [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The texts of the pushtaha were written on a single broad strip of paperlike bast, made from the inner bark of the alim tree treated with a rice-flour paste. Once the strip had been trimmed to the desired width, it was folded like an accordion to create individual "pages" for the texts; the ends of the strip were attached to wood panels, which served as book covers. The texts were recorded in a resinbased ink and were read in columns from the top to the bottom of the page and from left to right. They were written continuously, without any punctuation or space between words.

Many pushtaha are also extensively illustrated with images of supernatural beings, ritual paraphernalia, and related subjects. Rather than containing a fixed series of texts, pushtaha served essentially as notebooks in which, during his apprenticeship, the datu (or at times his teacher or a professional scribe) wrote down the information he thought necessary to correctly perform his duties. As a result, the books are somewhat idiosyncratic; although the texts they contain can be translated, they assume a prior familiarity with the subject matter that often makes them difficult to interpret precisely.

Pushtaha are typically divided into several sections, each of which covers a specific topic. The opening pages generally record the names of the succession of datu, often going back many generations, through whom the knowledge has been transmitted, ending with the individual who owned the book. The sections that follow are roughly divided by subject into benevolent magic, malevolent magic, ceremonial procedures, medicine and curing, and divination. They can contain instructions on subjects as diverse as the manufacture of amulets, the use of firearms, the preparation of medicines, and recipes for malevolent curries to be fed to creditors.

Reportedly of Toba Batak origin, the Metropolitan's pushtaha is as yet untranslated and its exact contents remain uncertain. Its profuse illustrations depict fantastic creatures that almost certainly represent supernatural rather than earthly beings. The front cover, like that of a number of pushtaha and other ritual paraphernalia, is adorned with the image of a lizard. This likely represents Boraspati Ni Tano, an agricultural deity associated with fertility who is manifest on earth in the form of a lizard. Similar lizard images adorn the doors of Batak rice granaries. Because of their close association with Boraspati Ni Tano, lizards were presented with ceremonial offerings of rice, and killing them was strictly forbidden.

Perminangken (Container for Magical Substances)

Perminangken , vessels containing magical substances formed an indispensable element of the datu's ritual paraphernalia. Such containers were fashioned from a variety of materials, such as horn, bamboo, metal and Chinese trade ceramics and were primarily used to hold pukpuk, the most potent supernatural substances possessed by a datu. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Toba Batak perminangken (container for magical substances) that dates to the 19th-early 20th century. It is made of wood, Chinese trade ceramic and is inches 34.3 centimeters (13 inches) tall.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Endowed with powerful magical properties, which could be harnessed for either protective or 119 malevolent purposes, pukpuk was used to supernaturally enliven ritual objects, such as staffs and certain types of human images. The pukpuk was applied to the object's surface or inserted into specially made holes that were later plugged with wood pegs to seal the power within. 4 The materials and ornamentation of Batak containers reflect the enormous power and value of the substances they contained. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The present work consists of a wood stopper, carved by a Batak artist, fitted to a 17th or 18th-century green-glazed kendi, or water pot, from Fukien Province, in China. Traded extensively throughout Island Southeast Asia, ceramics from China, Vietnam, Thailand, and Japan were highly prized by many of the region's indigenous peoples.

The stopper depicts a human figure mounted on a horselike singa, a mythical creature associated with the nobility. Equestrian images in Batak art are linked with social prestige and supernatural power, and horses or horselike creatures often serve as mounts for supernatural beings and prominent ancestors. 9The present singa combines the head and neck of a horse, the horns of a water buffalo, and the legless body and tail of a bird or naga (serpent-dragon), and serves as a fearsome supernatural protector for its noble rider. The ornate curvilinear designs that adorn the body may be purely ornamental, or perhaps they are intended to evoke the reptilian scales of the naga. In contrast to the ornate surface of his mount, the body of the rider is unadorned except for a small waistba nd and a headcloth, which flows gracefully back from his face as if blown backward by the wind created b the velocity of his supernatural steed. The rider may represent the datu to whom the container belonged. If so, it is possible to speculate that the small human face that gazes back at the rider from the apex of the singa's horns represents the datu's pangulubalang (spirit helper).

Batak Life-Size Puppetry

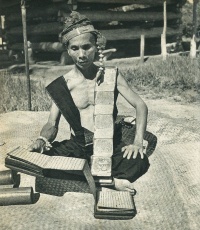

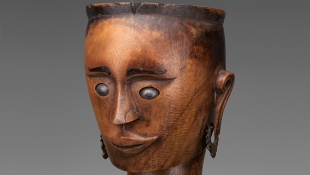

The Toba Batak employ nearly-lifesize gale-gale figures in their unique form of puppetry. Eric Kjellgren wrote: Perhaps the most distinctive Batak art form are the animated puppets known as si gale-gale, which are unique to the Toba Batak. Among the most complex puppets in the world, si gale-gale are equipped with movable heads, bodies, and complex jointed limbs fashioned from wood and controlled by a complex system of internal strings and levers that allows the puppets to move in a lifelike manner. The puppets were mounted on the front end of a long, fiat box through which the strings passed, allowing the puppeteer, who sat behind the box, to manipulate the puppet from some distance, giving the illusion that the figure was self-animated. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Si gale-gale probably originated during the mid-19th century, and the figures formerly played a specific and poignant role in the funeral ceremonies of the Toba Batak. Ancestors had, and in many respects continue to have, a central place in Batak religion. When an individual died, his or her living soul, or tondi, became an ancestral spirit, or begu, which, if his or her descendants performed the funeral rites correctly, enjoyed after death the same social prominence and wealth that he or she had when living. For a person to die childless, or to outlive his or her children, however, was a great tragedy, as without a child to perform the proper ceremonies his or her begu would be granted only an insignificant position in the spirit world. 8 This situation posed a threat to the community as well, since discontented begu could take vengeance on the living, bringing sickness or misfortune.

For highranking individuals who died without issue, the Toba Batak created and used a si gale-gale as a substitute child to perform the necessary funeral rites for the deceased. The puppets were either male or female, according to the gender of the dead.

Deftly manipulated by the puppeteer, the si gale-gale could gesture, dance, and even weep for its departed parent. Today the puppets are no longer used for funerary purposes, but si gale-gale performances are still held as part of local cultural events or to entertain foreign visitors. 13 With refined facial features, whose form may reflect the influence of Hindu-Javanese sculpture, the Metropolitan's si gale-gale head is among the finest examples of its type and originally formed part of a near-lifesize puppet. Analysis of the work reveals it to be a masterpiece of engineering as well as sculpture. It retains an elaborate internal mechanism controlled by strings (not visible in the accompanying photograph) that permitted the figure to extend a tablike tongue of wood.

Flexible pockets of rubber, positioned behind each eye, originally held damp moss or wet sponges, which, when squeezed by another internal mechanism activated by the puppeteer, allowed the figure to weep for its departed parent. The expressive eyebrows are inlaid with waterbuffalo horn ; the eyes are made from a lead-antimony alloy, and the pupils of resin ; and in the ears are the distinctive brass ornaments known as sitepal. As such ear ornaments were worn by both sexes, it is uncertain whether the present head represents a man or a woman.

The smaller, complete puppet is unequivocally male. It may have been an independent si gale-gale but is more likely an example of a second, more diminutive type of puppet that occasionally accompanied a larger si gale-gale figure. Although it is now stripped of its adornments, the puppet when in use would have been dressed, like the lifesize si gale-gale, in the headcloth and garments appropriate to its gender.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025