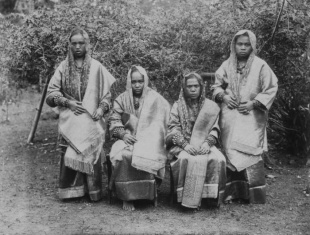

MINANGKABAU MATRIARCHAL SOCIETY

The Minangkabau represent one of the last remaining matrilineal societies in the world. Property is inherited down the female line and women pick their marriage partners and do the proposing. The only thing that a man can ask of his wife is that she remain faithful to him. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Because women own all the property, men travel the far corners of Indonesia and try to make their fortunes. The Minangkabau are sometimes called the Gypsies of Indonesia. Men are known for their wanderlust. Traveling is considered a mark of success. The Minangkabau are known throughout Southeast Asia as active traders and are among the most economically successful groups in Indonesia. Many Minangkabau villages in West Sumatra are dominated by women and the elderly while those in their communities elsewhere in Indonesia are dominated by young men and men in general. ~

A young boy has his primary responsibility to his mother’s and sisters’ clans. It is considered “customary” and ideal for married sisters to remain in their parental home, with their husbands having a sort of visiting status. Not everyone lives up to this ideal, however. In the 1990s, anthropologist Evelyn Blackwood studied a relatively conservative village in Sumatera Barat where only about 22 percent of the households were “matrihouses,” consisting of a mother and a married daughter or daughters. Nonetheless, there is a shared ideal among Minangkabau in which sisters and unmarried lineage members try to live close to one another or even in the same house. [Library of Congress]

The Minangkabau are organized in accordance with a unique administrative system called nagari that was established along village lines and follows a set of traditional customs and rules (“adat bsandi syarak, syarak bsandi Kitabullah”) that are in turn are based on the Koran and Islamic law. Each nagari has a mayor elected by the village council and an approved government-pointed official for a year. In recent years there has been a movement to strengthen the nagari system, and make it more independent from Jakarta. ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

MINANGKABAU PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU LIFE AND CULTURE: HOUSES, FOOD, CRAFTS, SPORTS factsanddetails.com

BUKITTINGGI AREA OF WEST SUMATRA: MINANGKABAU AND WORLD'S LARGEST FLOWER factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SUMATRA factsanddetails.com

SUMATRA: HISTORY, EARLY HUMANS, GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE factsanddetails.com

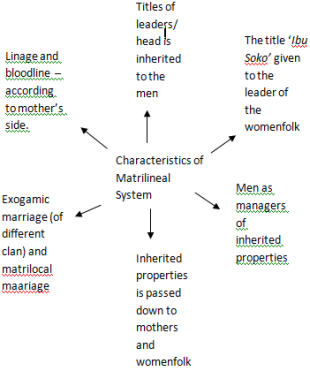

Minangkabau Matriarchal Groups and Organization

A Minangkabau person belongs to his or her mother's clan (suku) and traditionally lives with an extended family (paruik), meaning "common stomach or womb." This family consists of individuals who trace their ancestry back to a common matrilineal great-grandmother. The 96 named sukus trace back to four original sukus: Bodo, Caniago, Koto, and Piliang. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Suku play an important role in Minangkabau society. Varying in size depending in their history, they are made up of clans and subclans and fit into the nagari system. Each sub clan is made up of genealogically-linked units that are also the primarily land-owning units. They in turn are dived by sub units called “sabuah parulik” (“of one womb”), related kin that eat together, usually consisting of mother, grandchildren and son in law. Households are ruled by a senior matriarch who may have 70 people answering to her. Her judgment is regarded as final in all matters and everyone in her group is expected to defer to her. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The matriarchal system is no longer as strong as it once was and many people now live in nuclear family units in which men are not just guests, and children go to regular schools. Increasingly, married couples go off on merantau; in such situations, the woman’s role tends to change. When married couples reside in urban areas or outside the Minangkabau region, women lose some of their social and economic rights in property. One apparent consequence is an increased likelihood of divorce.

Minangkabau Family Life

Every Minangkabau belongs to his or her mother’s clan. The traditional domestic unit is a woman, her married and unmarried daughters, and her daughter’s children. Traditionally, fathers have little to do with raising the children. It is the uncle on the mother’s side that sees that the children are looked after and help arrange their marriage. But that is less the case today. Both mothers and fathers play a major role in childrearing. ~

As the nuclear family has increasingly replaced the extended family as the social norm, the importance of the father and his relatives has grown. It has become more common for a deceased man’s wife and children to dispute the traditional rights of his sister’s children to inherit his property. Traditionally, Minangkabau custom distinguished between harato pusako—property such as land and heirlooms held permanently by the suku or its branches—and harato pacarian, usually movable property acquired by a man, which he was free to pass on according to his wishes. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Birth was traditionally marked by several rituals, though many are now declining in importance. These included a ceremony in the sixth month of pregnancy; music played on talempong metallophones to welcome the newborn; burial of the placenta; the baby’s first contact with the ground at forty days; the first haircut; and, at three months, a formal visit to the father’s family. For girls, a ceremony known as menata kondai (“arranging the hair”) marked the onset of menstruation and served as a parallel to circumcision for boys.

Minangkabau Ideas About Gender

Contemporary Minangkabau gender relations reflect a tension between matrilineal tradition and patriarchal Islamic and national ideologies. Women—especially mothers—continue to play a central role in family life and often hold authority over lineage property, particularly rice land. Senior women (bundo kanduang) traditionally influence community decisions, though they are expected to speak indirectly rather than assertively.

At the same time, men occupy many formal authority roles, supported by Islamic ideas and state policies. Men traditionally manage their sisters’ property, not their wives’, and families value male lineage and “good descent” when arranging marriages. Colonial and modern Indonesian governments strengthened male leadership by recognizing men as household heads, directing development programs to them, and redefining bundo kanduang as idealized mothers rather than powerful lineage leaders.

Modernization and migration have further shifted power toward the nuclear family, reducing the influence of extended kin groups and senior women. Younger women may now increase their status through their husbands’ positions in state or bureaucratic systems rather than through matrilineal rank alone.

Minangkabau Marriage and Weddings

Members of the same clan are not supposed to marry. Cross-cousin marriages are preferred, preferably between a woman and her sister’s Custom preferred a man to marry his maternal uncle's daughter, though he might also choose his paternal aunt's daughter or the sister of his sister's husband; today, the choice is not so restricted). Within the paruik, children's interaction with their mother's siblings is hardly less close than that with their parents. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditionally, married men slept as guests in the houses of their wives. Each married woman had a room where she could receive her husband. Unmarried boys used to live in “sarau” (communal buildings) where they learned “silat” (traditional martial arts) and memorized the Koran under the guidance of a religious teacher. ~

“Formerly, a husband visited his wife only at night, retaining residence in his mother's village; these days, he moves into her house after the wedding. If a man takes more than one wife (a practice condemned by younger people), he commutes between their houses, which may mean between one house in his native place and another where he has migrated. For children, it was the mother's eldest brother (mamak) who served as the male authority figure; the mamak, moreover, managed the affairs of the paruik in general. The mamak's relations with his sister's husband tends to be formal. Parents-in-law, on the other hand, are known to spoil their children-in-law. If a man migrates with his wife, his parents-in-law may join them, while his own parents will not. After divorce, the husband must move away, leaving the children with his wife. ^^

“Because of matrilineal traditions, the wedding process among the Minangkabau does not conform to the pattern general to Indonesia. Not only men but also women may issue a proposal (via intermediaries, as usual elsewhere). Despite the requirements of Islamic law, a Minangkabau man does not pay a bride-price. On the other hand, the bride's family may pay the groom's an uang jemputan (handed over during the ceremony). Of greater importance is the exchange of symbolic goods, such as krisses (short daggers), between the two families. Brides wear elaborate gold headdresses. Sometimes they wear battery-powered headdress that looks like a bouquet of Christmas lights.

Minangkabau Adat (Customs) and Etiquette

Minangkabau adat (traditional law and customs) is influenced by Minangkabau matrilineal and Islamic traditions and summed up by the philosophy: "Adat basandi syarak, syarak basandi Kitabullah" (Customs are based on Islamic Law, Islamic Law is based on the Quran) and "Syarak mangato, Adat mamakai" (Sharia speaks, Adat is practiced), meaning Islamic teachings guide the application of customs. .

Minangkabau adat creates a dynamic system where traditional customs and Islamic faith are intertwined. Women (Bundo Kanduang) manage the household and lineage, while men (Datuak Pengulu) serve as clan speakers and leaders in public spheres, fostering interdependence.The system emphasizes community, mutual responsibility, and the importance of elders, with sayings (pepatah-petitih) guiding behavior. Cultural expressions include ceremonial orations (pidato adat) and folk theater (Randai), both rooted in adat.

Social etiquette requires that speech and behavior convey deference to elders, formality toward affinal relatives, and patient affection toward those who are younger; people of the same age, even when strangers, are expected to show mutual respect. Parents generally discipline children out of earshot of others, though at times correction may be intentionally public. Women who are close kin or intimate friends may embrace after a long separation, but it is improper for a man to embrace even a female relative, and some maintain that men and women should not shake hands at all. Women are also expected to observe restrictions on posture and public presence: they should not squat as men do, nor sit alone along roadsides or in places commonly frequented by men. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditionally, interaction between unmarried young men and women was highly restricted; for example, a boy and his uncle’s daughter might exchange glances only at major ceremonial gatherings. In parts of Pesisir Selatan, weddings provided a sanctioned occasion for such encounters. Young men would enter a house playing tambourines, while young women sat above in the pagu (open attic) and scattered flowers below. A young woman might lower a flower and a cigarette on a string to signal interest in a particular man, who would respond by sending back a ring or other small valuable wrapped in cloth.

Minangkabau Property and Law

Property is still largely handed down from wife to daughter. The inheritance system is somewhat complicated and involves: 1) earned property, which is passed down through households to either son or daughter often in line with Islamic law; and 2) ancestral property which is handed down from mother to daughter under the supervision of the clan. Most agriculture land is the latter. A man's children are not his clan's heirs. Instead, they are heirs of his wife's clan. When a man dies, he has to leave his possession of clan properties to the children of his sisters.~

Landholding is one of the crucial functions of the suku (female lineage unit). Because Minangkabau men, like Acehnese men, often migrate to seek experience, wealth, and commercial success, the women’s kin group is responsible for maintaining the continuity of the family and the distribution and cultivation of the land. These family groups, however, are typically led by a penghulu (headman), elected by groups of lineage leaders. With the agrarian base of the Minangkabau economy in decline, the suku—as a landholding unit—has also been declining somewhat in importance, especially in urban areas. Indeed, the position of penghulu is not always filled after the death of the incumbent, particularly if lineage members are not willing to bear the expense of the ceremony required to install a new penghulu. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The traditions of sharia—in which inheritance laws favor males— and indigenous female-oriented adat are often depicted as conflicting forces in Minangkabau society. The male-oriented sharia appears to offer young men something of a balance against the dominance of law in local villages, which forces a young man to wait passively for a marriage proposal from some young woman’s family. By acquiring property and education through merantau experience, a young man can attempt to influence his own destiny in positive ways. *

A village council made up of lineage heads (penghulu, all male) oversees local affairs, although under the modern Indonesian state its role is largely limited to mediating disputes. Traditionally, village leadership was shared among four groups: the niniek mamak, or heads of the paruik (extended matrilineal families); religious officials such as the imam and khatib; the cerdik pandai, individuals valued for their education; and the bundo kanduang, senior women. In contemporary society, wealth and education—both secular and religious—often carry as much or more weight than hereditary titles in determining status. Not all Minangkabau followed aristocratic principles: communities adhering to Koto-Piliang norms, as well as those in Aceh-influenced Pariaman, recognized hereditary rank, while groups following the Bodi-Caniago tradition favored more egalitarian arrangements, including the election rather than inheritance of penghulu. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025