MINANGKABAU WORK AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITY

Agriculture remains the principal livelihood for most Minangkabau. Wet-rice cultivation is the foundation of subsistence, while dry-field crops such as peanuts, potatoes, cabbage, tomatoes, and chilies are grown primarily for market sale. In more remote hilly regions, farmers practice swidden cultivation, initially planting dry rice, maize, cassava, pumpkins, and similar crops. After several years of fallow, these plots are converted to perennial plantings—rubber, cloves, cinnamon, pepper, coffee, coconut and sugar palm, or fruit trees—which allow households to participate more fully in the cash economy. Minangkabau households also raise chickens, ducks, cattle, water buffalo, and goats for meat, while fishing in the sea, lakes, and artificial ponds provides an important supplementary source of income. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Because land is often scarce and agricultural returns limited, many Minangkabau pursue livelihoods beyond farming. The long-standing tradition of merantau—migration in search of experience and wealth—encourages mobility and entrepreneurship. As a result, Minangkabau traders and business owners play a prominent role in the regional economy, dominating local commerce and marketing both agricultural produce and village-based craft specialties.

The Minangkabau are widely recognized for a strong entrepreneurial tradition, evident in the many businesses they operate across Indonesia as well as in Malaysia and Singapore. Their trading networks date back at least to the seventh century, when Minangkabau merchants were active in Sumatra and the Malacca Strait. By the eighteenth century they had become especially successful in the spice trade, laying the foundations for an extensive overseas commercial network that remains influential today. This entrepreneurial culture has produced several prominent business figures and substantial accumulated wealth. During Indonesia’s New Order period, however, Minangkabau entrepreneurs faced disadvantages due to limited state support for pribumi business interests. [Source: Wikipedia]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MINANGKABAU PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU: THE WORLD’S LARGEST MATRIARCHAL SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

WEST SUMATRA: MINANGKABAU, UNESCO SITES, AND RAINFOREST PARKS factsanddetails.com

BUKITTINGGI AREA OF WEST SUMATRA: MINANGKABAU AND WORLD'S LARGEST FLOWER factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SUMATRA factsanddetails.com

SUMATRA: HISTORY, EARLY HUMANS, GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE factsanddetails.com

Minangkabau Villages

Minangkabau villages are called nagari. Each nagari state or village is a self-sufficient community with agricultural lands, gardens, houses, prayer houses, a mosque, and a community meeting hall. Usually there is a central area with some scattered coffee shops. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Houses are organized along roads, are shaded by fruit trees and surrounded by wet-rice fields. Beyond them are dry fields that produce commercial crops such as coffee, cinnamon, rubber and fruit. The nature of economic activities varies with the location. Those on the coast are more into trade and fishing. Those in flat areas produce wet rice; in the mountains, commercial crops. ~

A nagari is composed of two main zones: the nagari proper, which includes residential houses and wet-rice fields, and the taratak, encompassing forests, dry-field agriculture, and sometimes the dwellings of landless caretakers. The nagari proper typically contains a mosque, a village council hall, a space for a weekly or twice-weekly market, and one or more surau—prayer halls that also serve as sleeping quarters for unmarried men. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The clusters of houses in a Minangkabau village are associated with different matrilineal lineages, which are local branches of widely dispersed suku. Lineages descended from the village founders (urang asa) hold rights to more land than later settlers, and their lineage head alone is entitled to bear a formal title. Among lineages that arrived subsequently, those—often related to the urang asa line—that possessed status in their place of origin were eventually able to acquire land and achieve near-equality with the founding lineage, though they remained barred from holding the principal title. Other later-arriving lineages occupy a subordinate position, being obligated to serve the dominant groups in various ways; in cases where a lineage is known to have slave ancestry, its members may also be avoided as marriage partners.

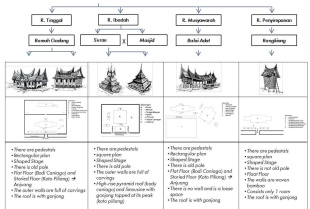

Traditional Minangkabau Houses

The traditional Minangkabau house, or rumah gadang (“big house”), is raised about two meters (6.5 feet) above the ground on wooden pillars and is distinguished by its dramatic, upward-curving roof ridges that taper to sharp points, often likened to water buffalo horns. These soaring saddleback roofs are among the most graceful architectural forms in Indonesia and belong to a wider Austronesian tradition of sloping roof designs that extends across the archipelago and into the Pacific. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Oriented north–south, the house is entered by a roofed staircase leading to a door on one of the long sides. Inside is a large central hall where household members work, gather, and socialize. Along the back wall are a series of rooms (bilik) for the married sisters of the lineage, added sequentially as each woman marries; the spacing of the main pillars, set about 3 meters (10 feet) apart, determines the placement of these partitions. In some houses, one end of the floor is raised to form an anjueng, a ceremonial sitting area reserved for people of superior status; where no anjueng exists, this space is occupied by a room for the youngest sister and her husband. A separate kitchen building stands behind the house and is reached by a small bridge. In elaborate aristocratic houses, even the floors tilt upward at the ends, echoing the arching roofline.

The rumah gadang reflects the matrilineal organization of Minangkabau society, in which descent passes through women, husbands reside in their wives’ houses, and women inherit both houses and ancestral land. Historically, newly married women occupied one end of the house, while older women past childbearing age lived at the other, so that movement through the house mirrored a woman’s life course. Although the Minangkabau adopted Islam in the sixteenth century, this matrilineal system has continued uninterrupted into the present.

Construction relies on mortised post-and-beam framing without nails; wooden pegs and wedges secure the structure, which rests on elevated piers. In some older houses, wall posts lean outward to accentuate the sloping roof. Roofs were traditionally thatched with durable black sugar-palm fiber, reputed to last for centuries, and walls were covered with carved and painted wooden panels.

Today, rumah gadang are far less common than in the past, having been largely replaced by smaller single-family houses, often called tungkuih nasi (“rice packets”) because their roofs lack the hornlike projections. Many families maintain a great house primarily as a symbol of lineage identity and prestige while living in modern concrete homes for comfort and convenience. In recent decades, however, the rumah gadang has experienced a revival as a marker of status and cultural identity, frequently financed by remittances from family members working in urban areas.

The arching roof forms are widely said to symbolize paired water buffalo horns—animals associated with wealth, ritual importance, and the Minangkabau name itself, often linked to the phrase minang kerbau (“winning water buffalo”). Some interpretations go further, suggesting that the half-circle formed by the curving rooflines represents a cosmological duality, with the visible structure completed by an unseen arc of an upper, invisible realm. In this view, Minangkabau roofs simultaneously evoke both an emblematic animal and the structure of the cosmos.

Minangkabau Food and Cuisine

Rice is the staple of the Minangkabau diet. Meals are typically accompanied by samba (side dishes), most commonly salted or dried fish and boiled vegetables such as cabbage, water spinach, cassava or papaya leaves, eggplant, amaranth, banana blossom, and other greens. Meat dishes—never pork—are eaten less frequently and are usually fried in coconut oil or slowly cooked in coconut milk with generous amounts of chili and spices, including garlic, shallots, ginger, galangal, turmeric, pepper, salt, and lemongrass. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Wikipedia]

The most celebrated Minangkabau dish is rendang, in which chunks of beef or water buffalo are simmered for hours in coconut milk and spices until the liquid reduces to a thick, oily coating. This method preserves the meat for long periods, making it especially suitable for travel. Other well-known dishes include gulai kambing (goat cooked in a coconut milk curry), dendeng (spiced dried beef), dendeng balado (dried beef with chili sauce), singgang ayam (fried chicken), soto Padang, and sate Padang. A traditional beverage is kopi daun, a tea made from dried coffee leaves.

Cooking holds a central place in Minangkabau culture, shaped in part by the frequent hosting of ceremonial feasts that demand abundant and carefully prepared food. Minangkabau cuisine is widely known for its rich use of coconut milk and chili, and is often described as resting on three core elements: bareh (rice), gulai (curried dishes), and lado (chili). Like much Sumatran cooking, it reflects Indian and Middle Eastern influences in its spice blends and curry-based preparations. All dishes conform to Islamic dietary laws: alcohol, pork, and lard are avoided, and traditional cooking relies on natural ingredients rather than chemical additives. Many dishes require long, complex preparation, contributing to their depth of flavor and durability.

Minangkabau food is most familiar to Indonesians through Padang restaurants, which are found throughout Indonesia and far beyond, including Malaysia, Singapore, Australia, the Netherlands, and the United States. In these restaurants, waiters present numerous dishes at once, and customers pay only for what they eat. Their popularity among non-Minangkabau diners stems not only from the food’s bold flavors but also from the assurance that all meat is halal. Rendang in particular has achieved international acclaim, frequently cited as one of the world’s most delicious dishes and officially recognized as one of Indonesia’s national foods.

Minangkabau Culture

The Minangkabau have a thing about water buffaloes. The roofs of their houses—which bow down deeply at mid-length and turn up steeply to gabled ends— are shaped like buffalo horns, and their favorite sports are water buffalo fighting and racing. Randai, the traditional folk theater of the Minangkabau, is performed during ceremonies and festivals. Music, singing, dance, drama and the silat martial art are all incorporated together and are based on the traditional stories and legends. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Clothes for men include shirts and trousers, as well as a peci cap, for everyday wear. Older men wear serawa, which are long pants with a drawstring, and a teluk belanga, a tunic, or a "Chinese" shirt. They sometimes wear a head cloth instead of a peci. Ceremonial attire for men consists of a tunic with short sleeves that widen toward the opening, trousers, a gold- and silver-embroidered songket cloth wrapped around the waist and hanging just below the knee, a sash over the shoulder, a saluak headdress, and a kris (short dagger) tucked in the front.[Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Women wear sarongs and long-sleeved kebayas, as well as tingkulaks, which are head wraps that cover the hair. Urban women who wear modern clothing put on traditional clothing while in the village. For ceremonial occasions women wear a baju kurung, a songket sarong with a matching sash over the shoulder, earrings, and several necklaces stacked on top of each other, as well as bracelets on both arms. The most distinctive aspect of women's attire is the headwear. The cloth is folded in a unique manner for each village to resemble horns (tanduk or tilakuang).

Minangkabau Literature and Folklore

The Minangkabau also have a rich oral culture and are known among other Indonesians for their love of talking and discussing politics and issues of the day in coffee shops. In the early twentieth century, Minangkabau authors writing in Malay for the Dutch colonial publisher Balai Pustaka produced novels that explored tensions between adat (custom) and modernity in Minangkabau society. Many of these works became foundational texts of modern Indonesian literature.

Traditional Minangkabau folklore include stories that tap into the belief that remote mountain or jungle spots may be “tampek-tampek nan sati” — “places charged with supernatural power." The Minangkabau fear spirits such as puntianak, who suck the blood out of infants through their soft spots (the fontanels) from afar. Palasiks are women with an innate, though uncontrollable, power to make children sick. People may enlist dukun, who are practitioners of magic and herbal medicine, to combat malevolent spirits or victimize others, as in menggasing, which involves sending poison into another's bloodstream through the air. As a defense, many carry amulets; a particularly potent one is crystallized elephant sperm. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The name Minangkabau means, literally, "victorious water buffalo"-a reference, according to oral tradition, to an epic battle between the local people and invading forces from the Majapahit Empire, which ruled the neighboring island of Java from the late thirteenth to the early sixteenth century. Rather than engage in battle, the leaders of both sides agreed to settle the tight through a ritual combat between two water buffalo. The Majapahit army selected a strong bull to be their champion, and the Minangkabau chose a hungry calf. During the contest, the calf, armed with knives strapped to the top of its head, attempted to nurse from the huge bull, stabbing it to death. A symbol of the Minangkabau victory, the paired horns of the water buffalo are a motif that appears widely in Minangkabau art, from the form of women 's headdresses to the steeply curving, double-peaked roofs of houses. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Minangkabau Music, Dance and Performing Arts

Minangkabau musical traditions include “saluang” (flute playing) and several forms of vocal performance, such as dendang (song), zikir (chanting in an Arabic style), and selawat (Qur’anic invocations). Musical accompaniment commonly features bamboo flutes (saluang and bansi), the tambourine (rebana), drums, the kecapi zither, and the violin. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Minangkabau dances are energetic and expressive. The fan dance depicts courtship and interaction between young men and women. Among the lively and colorful Minangkabau dances are the umbrella dance, in which men express their love to their girlfriends; the plate dance, involving dancing and leaping barefoot onto broken plates; and the candle dance, in which female dancers juggle plates with burning candles on them. The umbrella dance symbolizes romantic love and is often performed by a bride and groom.

Randai is a form of dance drama performed at weddings and other big events that features martial-arts-like pencak silat moves. This form of dances usually tells a story and is performed to gamelan music. Every Minangkabau boy learns it when he is growing up. The Mudo is form of mock battle that is learned by young men and sometimes performed. It too features pencak silat moves. ~

Other Minangkabau arts include “pepatah petitih” (wise sayings), “kaba” (narrative poems), “pantun” (Malay-like rhymed couplets). Rantak incorporates stylized martial-arts movements, and sauik randai conveys the joyful mood that follows a day of farming or fishing. Dabus consists of pencak silat martial arts movements presented as an artistic performance.At ceremonial events, especially weddings, participants readily improvise poetry in the forms of pantun and syair, as well as aphoristic expressions. Traditional oral literature includes the epic Kaba Cindur Mata.

Traditional Minangkabau Crafts

Traditional Minangkabau Crafts include making hand-loomed songket cloth with elaborate designs made from geometric patterns and floral designs; needle weaving, a labor-intensive process in which patters are made by removing threads and stitching the remaining threads together; and silver filigree jewelry. Only a few villages continue to produce the ceremonially important songket, cloth brocaded with gold and silver threads.

Intricate carving, often painted, decorates the pillars and walls of Rumah Gadang (traditional Minangkabau houses). Particular (usually plant) motifs correspond to different parts of the structure and symbolize virtues such as the tangguak lamah design, which signifies humility and courtesy. Carving is only practiced in certain villages, such as Pandai Sikek. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Rumah Gadang carvings usually take the form of circular or square lines with motifs such as vines, leafy roots, flowers, and fruit. The root pattern is usually circular, with roots aligned, coinciding, intertwining, and joining. Root branches or twigs curl outward, inward, upward, and downward. Other motifs found in the carvings of theRumah Gadang include geometric shapes such as triangles, squares, and parallelograms. Types of Rumah Gadang carvings include kaluak paku, pucuak tabuang, saluak aka, jalo, jarek, itiak pulang patang, saik galamai, and sikambang manis. [Source: Wikipedia]

Minangkabau Woman's Headdress

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Minangkabau woman's headdress dated 19th-early 20th century. It is made of wood and gold leaf is 26 centimeters (10.4 inches) wide. An accompanying bracelet dates to the same period and is made of wood, gold leaf and paint. It is 14.6 centimeters long.Eric Kjellgren wrote: This gilded headdress and bracelet were resplendent elements of the elaborate ceremonial attire worn by Minangkabau women and young girls. Fashioned from wood, the headdress faithfully reproduces the soft contours and complex patterns of a woman 's folded headcloth (tangkuluak). The artist has rendered in detail each of the overlapping layers of fabric, including the loose ends that drape down the back. The intricate, gilded relief carvings reproduce the patterns of Minangkabau textiles, whose lavish geometric designs are executed in gold thread. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The distinctive biconical form of the headdress represents the horns of the water buffalo (kabau), an animal central to the Minangkabau identity and culture. Although the Minangkabau have been Muslims since the sixteenth century, they practice Islam in accordance with the principles of their indigenous cultural institutions, known as adaik.

Headcloths, or their wood counterparts, were essential elements of a woman 's ceremonial attire, which also included a shoulder cloth, a tunic or blouse, and an anklelength skirt, as well as a variety of jewelry. Like the headdress, the bracelet is made from gilded wood, and it, too, replicates the features of another medium-in this case, metalwork. It is carved in the form of the bracelets known as a galang gadang, and its intricate surface designs reproduce the delicate patterns of hollow bracelets constructed from thin sheets of hammered gold.Such bracelets were worn by young women and girls; a mother passed down her bracelets to her daughter when the child was about nine years old.

Bracelets were typically worn in pairs, one on each arm. However, at her wedding, a young woman might wear as many as eight or nine, the larger bracelets, such as galang gadang, on the right arm and smaller types on the left. As in all Minangkabau art, the individual motifs that adorn the bracelets have, or once had, specific meanings. The lozenge-shaped motifs on the present work represent saik galamai, ceremonial cakes that are cut into small pieces of a similar shape. As the preparation of saik galamai requires several individua ls, the lozenge-shaped design alludes to the importance of cooperation in all endeavors.'

Minangkabau Sports and Games

The local form of martial arts is called kumango, a version of the pan-Malay-Indonesian silat. Bareback horse racing is also popular. A game played by children ages 5–15 is called galah. In this game, one team attempts to block the other team from running a course from a starting point to the end of the playing field and back. Males (and very rarely, females) of all ages enjoy catur harimau ("tiger chess"), a board game with stone playing pieces. In this game, one player's "tigers" attempt to eat up the other player's "goats." The movement and placement of the pieces requires skill and strategy. [

Water Buffalo Fighting is a favorite traditional Minangkabau sport. The fights are between two bulls of around equals size. They lock horns and push one another. The bull that gives up loses. It is not unusual for a bull to run in the crowd and everyone runs for cover. Betting can be quite intense. The biggest bullfights are held in the villages of Kota Bari and Batagak. Bareback horse racing is also popular. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Bull Racing (Pacu jawi) has been held for centuries in Tanah Datar, West Sumatra, to celebrate the end of the rice harvest. In the event, a jockey stands on a wooden plough and grips the tails of two loosely tied bulls as they charge through a muddy rice field for roughly 60–250 meters. Despite its name, it is not a competitive race: each pair runs alone, no winner is declared, and spectators judge the bulls by their speed, strength, and ability to run straight—traits that symbolize honor and moral uprightness. [Source: Wikipedia]

The event rotates among villages (nagari) in four districts of Tanah Datar and is staged when fields lie fallow between planting seasons, traditionally with Mount Marapi visible. Strong-performing bulls can be sold for two to three times their normal price, making prestige and profit key motivations for participants. The race is risky and chaotic, with frequent falls, splashing mud, and occasional charging bulls.

Pacu jawi takes place alongside a village festival (alek pacu jawi), featuring music, dance, decorated cattle, games, and fairs. In recent decades it has gained government support and become a major tourist attraction, renowned internationally through award-winning photography that captures its speed, drama, and muddy spectacle set against West Sumatra’s landscape.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025