TIBETAN ANIMALS

kiang (Tibetan wild asses) Tibet was once filled with wild animals and still is to some degree. In the old days many animals had no fear of humans. The Swedish explorer Sven Hedin wrote in the early 20th century, "The wild animals do not sense that man is their enemy. They know only the wolf and are alert against his cunning." The abundance of wildlife today is demonstrated by the large number of stiff, frozen and flattened road kills on the roads.

The mountains and forests of Tibet are home to a vast range of animal life, including 142 species of mammals, 473 species of birds, 49 species of reptiles, 44 species of amphibians, 64 species of fish and more than 2,300 species of insects. Wild animals found in Tibet include Assamese macaque, rhesus monkey, muntjac, chitral, serows, head-haired deer, wild cattle, red-spotted antelopes,leopards, clouded leopards, black bears, wild cats, red pandas, martens, river deer, white-lipped deer, wild yaks, Tibetan antelopes, wild donkeys, argalis, Mongolian gazelles, Tibetan eagles, marmots, Himalayan mouse hares, Himalayan ravens, foxes, wolves, lynxes, brown bears, blue sheep, and snow leopards. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

The Tibetan antelope (chiru), argali and wild yak are rare species particular to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. They are under state protection. The white-lipped deer (Thorold’s deer) found only in the eastern Tibetan plateau is of particular rarity. The black-necked crane and the Tibetan pheasant are under first-grade state protection. Other rare and threatened animals found in Tibet include the snow leopard, Tibetan takin, Himalayan black bear, blue sheep, musk deer, golden monkey, wild ass (kyang in Tibetan), Tibetan gazelle and Himalayan mouse hare.

There are many wolves in Tibet. They are strong enough to bring down a yak but are elusive and rarely seen. Sometimes they kill livestock. Marmots (known as chiwa or piya) are the most commonly seen animals in Tibet. Resembling giant golden woodchucks, they are rodents that live in burrows, behave somewhat like prairie dogs and make strange bird-like chirping noise when they are agitated. Marmots are called in Himalayan snow pigs in Tibet, Gansu, Sichuan and Qinghai. To catch them hunters simply wait around in the morning for them to emerge from their burrows so you can see where they live. Later the hunters return to the burrows light a fire and direct the smoke into the burrow. When the marmot escapes it is caught in a net. Himalayan pikas (also known as mouse hares and chipi) are also often seen. They have been observed on high slopes of Mt. Everest. According to the Guinness Book of Records, they are the highest living animal. A pika has been observed at an elevation of 20,106 feet.

Some scientists think that Tibet is the source of Ice Age mammals. Stephanie Pappas wrote in LiveScience: “High on the Tibetan Plateau, paleontologists have uncovered the skull of a previously unknown species of ancient rhino, a woolly furred animal that came equipped with a built-in snow shovel on its face. This curiosity, a flat, paddle-like horn that would have allowed it to brush away snow and find vegetation beneath, suggests the woolly rhinoceros was well-adapted for a cold, icy life in the Himalayas about 1 million years before the Ice Age. Those adaptations may have left the rhino perfectly poised to spread across Asia when global temperatures plummeted, ushering in the Ice Age. "We think that the Tibetan Plateau may be a cradle for the origins of some of the Ice Age giants," said study author Xiaoming Wang, a curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. Such large, furry mammals ruled the world during Earth's cold snap from 2.6 million to about 12,000 years ago. "It just happens to have the right environment to basically let animals acclimate themselves and be ready for the Ice Age cold." [Source: Stephanie Pappas, LiveScience, September 2, 2011; See Woolly Rhino Originated From Tibet? Under WOOLLY RHINOS AND CAVE BEARS factsanddetails.com ; Oldest Big Cat Fossil Found in Tibet See PREHISTORIC MAMMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: China.org article on Tibetan animals china.org.cn ;Animal Info animalinfo.org/country/china

articles under TIBETAN NATURE factsanddetails.com ; HIMALAYAN MOUNTAIN GOATS AND SHEEP factsanddetails.com ; SNOW LEOPARDS Factsanddetails.com/China ; SHAHTOOSH AND CHIRUS Factsanddetails.com/China ; YAKS Factsanddetails.com/China ; PIKAS factsanddetails.com; MARMOTS factsanddetails.com; ANIMALS AND PLANTS IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Himalayan Wildlife: Habitat and Conservation” by S. S. Negi Amazon.com;

“Stones of Silence” by George Schaller Amazon.com;

“Wild Animals of India, Burma, Malaya and Tibet” by Richard Lydekker Amazon.com ;

“Chinese Wildlife” ( Bradt Travel Wildlife Guides) by Martin Walters Amazon.com

“Birds of the Himalayas” (Pocket Photo Guides)

by Bikram Grewal and Otto Pfister Amazon.com

“Wildlife of India” by Bikram Grewal Amazon.com;

“Tibet's Hidden Wilderness: Wildlife and Nomads of the Chang Tang Reserve

by George B. Schaller Amazon.com

“Chang Tang A High and Holy Realm in the World”

by Liu Wulin Amazon.com

“Big Open: On Foot Across Tibert's Chang Tang”

by Rick Ridgeway , Galen Rowell, et al. Amazon.com;

“The Chiru of High Tibet: A True Story” by Jacqueline Briggs Martin and Linda Wingerter Amazon.com;

“Contesting Conservation: Shahtoosh Trade and Forest Management in Jammu and Kashmir, India” by Saloni Gupta Amazon.com

Animals in Different Parts of Tibet

Tibet's complex topography and widely varying climates result in an abundance of ecological niches for different groups of animals. The eastern and southern parts of the region are (were) largely covered with old growth forests, home to rare plants and animals. In the highlands are marmots, wolves, chiru (a kind of antelope) and a few wild yak. Dense forests mostly in eastern and southeastern Tibetan areas provide shelter for many precious animals such as sunbird, vulture, giant panda, golden-haired monkey, black leaf monkey, bear and ermine. The forests also produce precious medicines such as bear's gallbladder, musk, pilose antler, caterpillar fungus, snow lotus and glossy ganoderma. “Agkistrodon himalayanus” is a snake that lives as high 4,900 meters (16,000 feet) in the Himalayas

Himalayan rivers are often milky and full of sediment and have a source somewhere in Tibet. Sometimes the lower reaches are full of tropical vegetation. In the old days, tigers and rhinoceros roamed here. At an elevation of around 1,000 meters there are stubby trees and rhododendron. Sun birds and langur monkeys are often seen here. There are also tragopans, a turkey-size pheasant with red feathers decorated with white spots. The rhododendrons get progressively short as one climbs in elevation: 15-foot trees shrink to ground level bushes.

By 2,500 meters the rhododendrons have largely been replaced by conifers: mostly Himalayan fir and Bhutan pine. These trees have needles that are designed to shed snow and withstand cold temperatures. Sometimes you can see red pandas there. Above tree line is tundra-like vegetation, rissocky plants and occasional buckhorn bushes and junipers. Here you can find marmots and pikas that feed on grass and cushion plants and they in turn provide food for griffon vultures that soar in the thermals.

Above 3,500 meters much of the vegetation gives out except for harsh grasses that few animals other than yaks can feed on. In the winter there is usually snow. Throughout the year high winds blow at this elevation. With moisture alpine meadows can flourish up to an elevation of 6000 meters.

Biodiversity Hotspot: Himalayas

The Himalaya Hotspot is home to the world’s highest mountains, including Mt. Everest. The mountains rise abruptly, resulting in a diversity of ecosystems that range from alluvial grasslands and subtropical broadleaf forests to alpine meadows above the tree line. Vascular plants have even been recorded at more than 6,000 meters. The hotspot is home to important populations of numerous large birds and mammals, including vultures, tigers, elephants, rhinos and wild water buffalo.

VITAL SIGNS: 1) Hotspot Original Extent (km²) 741,706; 2) Hotspot Vegetation Remaining (km²) 185,427; 3) Endemic Plant Species 3,160; 4) Endemic Threatened Birds 8; 5) Endemic Threatened Mammals 4; 6) Endemic Threatened Amphibians 4; 7) Extinct Species? 0; 8) Human Population Density (people/km²) 123; 9) Area Protected (km²) 112,578; 10) Area Protected (km²) in Categories I-IV* 77,739. “Recorded extinctions since 1500. *Categories I-IV afford higher levels of protection.

Stretching in an arc over 3,000 kilometers of northern Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan and the northwestern and northeastern states of India, the Himalaya hotspot includes all of the world’s mountain peaks higher than 8,000 meters. This includes the world’s highest mountain, Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) as well as several of the world’s deepest river gorges.

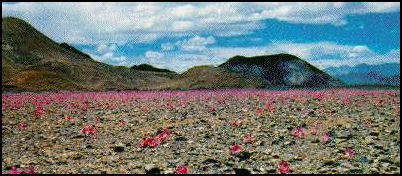

Chang Tang snow lillies

This immense mountain range, which covers nearly 750,000 km², has been divided into two regions: the Eastern Himalaya, which covers parts of Nepal, Bhutan, the northeast Indian states of West Bengal, Sikkim, Assam, and Arunachal Pradesh, southeast Tibet (China), and northern Myanmar; and the Western Himalaya, covering the Kumaon-Garhwal, northwest Kashmir, and northern Pakistan. While these divisions are largely artificial, the deep defile carved by the antecedent Kali Gandaki River between the Annapurna and Dhaulagiri mountains has been an effective dispersal barrier to many species.

The abrupt rise of the Himalayan Mountains from less than 500 meters to more than 8,000 meters results in a diversity of ecosystems that range, in only a couple of hundred kilometers, from alluvial grasslands (among the tallest in the world) and subtropical broadleaf forests along the foothills to temperate broadleaf forests in the mid hills, mixed conifer and conifer forests in the higher hills, and alpine meadows above the treeline.

Plants in Tibet

Over 6,400 species of plants have been identified in Tibet. Many of them are rare and endemic. These plants include about 2,000 varieties of medical herbs used in the traditional medicinal systems of Tibet, China and India. Rhododendron, saffron, bottle-brush tree, high mountain rhubarb, Himalayan alpine serratula, falconer tree and hellebonne are among the many plants found in Tibet. About 400 species of rhododendron are found in the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau, about half of the world's rhododendron total species. Gyirong and Yadong counties and Chentang Town in western Tibet, and Medog and Zayu counties and the Lhoyu region in southeast Tibet are particularly rich in rare plant life and species . Even harsh northern Tibet contains more than 100 kinds of plants.

Flowering plants (“Ermania himalayenis”) have been found at an elevation of 21,000 feet in the Himalayas. “Saussurea”, a Himalayan plant, is covered with a massive dome of white fur. It has a small hole where pollinating insects that can reach the flowers. The flowers and leaves are barely visible. Juniper trees and willows are common in central Tibet. Wild flowers include pansies, oleanders and “tsi-tog”, an indigenous high-altitude pink flower. In the lower altitude border areas, you can find forests of pines, spruce and fir. In parts of eastern Tibet which receive a fair amount of rainfall you can see oaks, elms, birches and subtropical plants such as rhododendrons and azaleas. In the Everest area there are rhododendron trees over 60 feet tall. Lichens grow up to 18,000 feet in the Himalayas and are one of the few living things that grow in the Antarctic and the islands in the Arctic.

Tibet is also one of China's largest forest areas, preserving intact primeval forests. Most of the plants in Tibet are distributed in southeast Tibet, like Medog, Chayu, Luoyu and Menyu. Almost all the main plant species from the tropical to the frigid zones of the northern hemisphere are found here. Forestry reserves exceed 2.08 billion cubic meters and the forest coverage rate is 9.84 percent. Common species include Himalayan pine, alpine larch, Pinus yunnanensis, Pinus armandis, Himalayan spruce, Himalayan fir, hard-stemmed long bract fir, hemlock, Monterey Larix potaniniis, Tibetan larch, Tibetan cypress and Chinese juniper. Spruce, fir, and hemlock are distributed most widely, accounting for 48 percent of Tibet's forests by area and 61 percent by stock. They are found mainly in the humid sub-alpine zones of the Himalayas, Nyainqentanglha, and Hengduan ranges. There are about 926,000 hectares of pine forest in Tibet. Two species, the Tibetan longleaf pine and the Tibetan lacebark pine, are included in the State's tree protection list. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China; Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

snow lilly

Many plants in Tibet have medicinal value. There are more than 1,000 wild plants used for medicine, 400 of which are medicinal herbs most often used. There are more than 1,000 kinds of wild plants used for medicine, including 400 commonly used ones. Particularly well-known medicinal plants include Chinese caterpillar fungus, Fritillaria Thunbergii, Rhizoma Picrorhizae, rhubarb, Rhizoma Gastrodiae, pseudo-ginseng, Codonopsis Pilosula, Radix Gentiane Macrophyllae, Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae, glossy ganoderma, and Caulis Spatholobi. In addition, there are over 200 known species of fungi, including the famous edible Pine mushroom, hedgehog hydnum, zhangzi fungus, mushrooms, black fungi, tremellas, and yellow fungi. There are also fungi with medical use such as tuckahoes, songganlan (Cryptoporus Volvatus (Peck) Schear), and stone-like omphalias.

One of the best place to see the various plants of Tibet is Nyingchi, east Tibet. There is a famous forest known as Lunang Forest which is located at 3,700 meters above sea level, alongside the Sichuan Tibet Highway. The Lunang Forest is made up of bushes, dragon spruces, maple trees and pines. The landscape here is particularly beautiful. There are snow mountains, glaciers, old-growth forests, villages and rivers nearby. Due to Nyingchi's relatively lower altitude, some tourists travelling to Tibet first fly to Nyingchi and then travel to Lhasa.

Particularly well known medicine plants include Chinese caterpillar fungus, Fritillaria Thunbergii, Rhizoma Picrorhizae, rhubarb, Rhizoma Gastrodiae, pseudo-ginseng, Codonopsis Pilosula, Radix Gentiane Macrophyllae, Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae, glossy ganoderma, and Caulis Spatholobi. In addition, there are over 200 known species of fungi, including famous edible fungi songrong, hedgehog hydnum, zhangzi fungus, mush rooms, black fungi, tremellas and yellow fungi. Fungi for medical use include tuckahoes, songganlan, stone-like omphalias.

Endangered Species in Tibet

Among the endangered species found in Tibet are the snow leopard, ibex, musk deer, Tibetan antelope (chiru), Tibetan wild ass, , black necked crane and wild yak. The bharal, (blue sheep) of the Himalayas is very closely related to both goats and sheep. They are tan, white and gray. Their color camouflages them well on a rocky mountain landscape.

Living in some parts of Tibet are rare white lipped deer, and macaques (a kind of monkey) that survive in the winter by eating insects and vegetation under the snow. Himalayan brown bears — virtually the same as North American grizzly bears and Russian brown bears — are very rare, only a few dozen remain. Also known as Tibetan brown bears, they stand two meters tall and are found only in the forests of southern Tibet and the Chantang plateau.

Large herds of wild yak, Tibetan antelope, wild donkeys and deer that were seen on the Tibetan plateau during a source-to-sea expedition along the Yangtze River in 1989, have largely been slaughtered by poachers for the animal's meat and hides. Items from endangered animals for sale in Western China include wolf and snow leopard pelts, fox furs, bearskins, and carcasses of Imperial eagles.

Tibetan Blue Bear

Tibetan blue bears (Ursus arctos pruinosus) are also called Tibetan bears, Tibetan brown bears, horse bears and Himalayan blue bears They are a subspecies of the brown bear found in the eastern Tibetan plateau. Some bears found in the Himalayas, sometimes called Bears called Himalayan snow bears, are not Himalayan brown bears but are from a robust population of Tibetan blue bears. In Tibetan Tibetan blue bears are known as Dom gyamuk. One of the rarest subspecies of bear in the world, the blue bear is rarely sighted in the wild. They are known in the west only through a small number of fur and bone samples. They were first classified in 1854. [Source: Wikipedia]

Tibetan blue bears are moderately-sized with long, shaggy fur. Both dark-colored and light-colored variants are encountered, with colors in between being the most common. Tibetan blue bears often have a yellow-brown or whitish cape forming a saddle-shaped marking across the shoulders. The yellowish-brown fur around the neck, chest and shoulders looks sort of like a collar. No other brown bear subspecies possesses this in a mature state. Like the Himalayan brown bear, the ears are relatively prominent. The skull is distinguished by its relatively flattened choanae, an arch-like curve of the molar row and large teeth, probably in correlation to its particularly carnivorous habits.

illustration of a Tibetan blue bear made in 1892

The blue bear is notable for having been suggested as one possible inspiration for sightings associated with the legend of the yeti. A 1960 expedition to search for evidence of the yeti, led by Sir Edmund Hillary, returned with two scraps of fur that had been identified by locals as 'yeti fur' that were later scientifically identified as being portions of the pelt of a blue bear. While it is unlikely that the blue bear generally occupies the high mountain peaks and snow fields where the yeti is sometimes sighted, it is possible that the occasional specimen might be observed traveling through these regions during times of reduced food supply, or in search of a mate. However, the limited information available about the habits and range of the blue bear makes such speculation difficult to confirm.

Tibetan blue bears are much feared in regions where they are found. According to some Chinese sources, 1,500 people are killed a year by these bears, a figure that seems to be too large to be true, but some say is credible and caused by the clearing of new farm land in the bear’s habitat. Becasue few local people have guns the bears often have te upper hand in confrontations. [Source: the book “Bears of the World”by Terry Domico]

The exact conservation status of the blue bear is unknown, due to limited information. However, in the United States trade in blue bear specimens or products is restricted by the Endangered Species Act. It is also listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) as a protected species. It is threatened by the use of bear bile in traditional Chinese medicine and habitat encroachment. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Gobi brown bear is sometimes classified as being of the same subspecies as the Tibetan blue bear; this is based on morphological similarities, and the belief that the desert-dwelling Gobi bear represents a relict population of the blue bear. However, the Gobi bear is sometimes classified as its own subspecies, and closely resembles other Asian brown bears.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BROWN BEAR SUBSPECIES: BIG, RARE ONES AND WHERE THEY LIVE factsanddetails.com

BROWN BEARS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, SIZE factsanddetails.com

BROWN BEAR FEEDING: DIET, HABITS, HUNTING, SALMON factsanddetails.com

BROWN BEAR BEHAVIOR: SENSES, HIBERNATION, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BEARS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, HABITAT, HUMANS, PIZZLIES factsanddetails.com

BEAR CHARACTERISTICS: PHYSIOLOGY, DIET, LIFESPAN factsanddetails.com

BEAR HIBERNATION, REPRODUCTION, CUBS factsanddetails.com

Himalayan Brown Bears

Himalayan brown bears(Ursus arctos isabellinus) are also known as red bear and isabelline bears. They live in northern Nepal, North India and Northern Pakistan, with many in the contested region of Jammu and Kashmir. They are quite distinctive physically form other brown bears in that have a reddish-brown or sandy-brown coat color with silver-tipped hairs and relatively large ears. These bears are smaller than most other brown bears. They prefer high altitude forests and alpine meadows. [Source: Wikipedia]

Himalayan brown bears are Critically Endangered. About the size of a grizzly, Himalayan brown bear males range from 1.5 to 2.2 meters (4. 9 to 7.3 feet) in length, while females are 1.4 to 1.8 meters (4.5 in to 6 feet) in) long. They mainly live above tree tree line and feeds on grasses, roots and occasionally mountain sheep killed in avalanches. Herders used to sometimes kill the mothers and capture the cubs which were sold to itinerate entertainers for use as dancing bears. [Source: the book “Bears of the World”by Terry Domico]

Himalayan brown bears are the largest mammal in the Himalayas. They are omnivorous and hibernate in dens during the winter. The bears go into hibernation around October and emerge during April and May. Hibernation usually occurs in a den or cave made by the bear. Himalayan brown bears eat grasses, roots, fruits, berries and other plants as well as insects and small mammals. They have been observed eating sheep and goats and occasionally take animals from villagers. [Source: Wikipedia]

One of the last strongholds of Himalayan brown bears is the Deosai Plains, 32 kilometers south of Skardu in northern Pakistan, not far from K2, and China. At an average elevation of 4000 meters, Deosai is the home of Deosai National Park, on of the world’s highest national parks. With Nanga Parbat mountain in the background, the park features crystal streams, unique fauna and flora, including 150 species of medicinal plants. On this rolling grassland there are no trees and the area is covered in snow for seven months of the year. Spring comes to Deosai in August when millions of wild flowers bloom. The park covers 3,5840 square kilometers. [Source: Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation. tourism.gov.pk ]

See Separate Article: WILD ANIMALS IN PAKISTAN: factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Deer

A herd of Tibet red deer, a species thought to have been extinct and not seen in the wild for 50 years, was rediscovered in a remote valley in southeastern Tibet near where China, Bhutan and India meet by the eminent natural George B. Schaller. The search for the deer began in 1987 when several captive deer were seen in Lhasa. "From past records, I knew the approximate range of the Tibet Red deer, or shou, as it is sometimes called, so we made a special effort to look at those areas to see if any deer survived," Schaller said.

A relative of the North American elk, the Tibetan red deer stand about four feet at the shoulder and has distinctive five-point antlers and a white patch on its rump. Mature males weigh about 250 pounds. The animals live in alpine meadows above 13,000 feet, Many of the deer disappeared in the 1960s and 70s as a result of hunting. Later some Tibet red deer were rediscovered 75 miles east of Lhasa in a remote in valley. There are plans to set up reserves and establish conservation teams for the deer, which are valued for their meat and antlers, which are used in oriental medicine.

The McNeill's deer of the Tibetan plateau is one of the world's most endangered animals. Many people in China raise deer on farms primarily for the traditional Chinese medicine trade. Deer antlers are cut up into slices and made into a tea with other herbs that are taken to treat a number of ailments.

See Deer Under WILD ANIMALS IN CHINA See Separate Article factsanddetails.com and Musk Deer Under See Separate Article DEER, ANTELOPE AND DEER-LIKE ANIMALS IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

White-Lipped Deer

White-lipped deer (Przewalskium albirostris) are also known as Thorold's deers and to Tibetans as "shor". A threatened species, they are deer found in high-altitude rhododendron and coniferous forests, grasslands, shrubland and alpine meadows in the eastern Tibetan Plateau at elevations of 3,500 to 5,000 meters (11,483 to 16,404 feet), mainly in Qinghai Province and Tibet as well as areas further north in central Western China. Rough terrain and hunting pressure by humans are the main reasons for their patchy distribution.

White-lipped deer are one of the larger ungulate mammals in their range, and fill an ecological niche similar to the Tibetan red deer. in 1998, it was estimated that about 7,000 white-lipped deer remained in the wild. As of early 2011, more than 100 of the deer were kept globally in Species360-registered zoos. Many people in China raisie these deer on farms. White-lipped deer have been recorded living 19 years in captivity. Those in the wild may for 16 to 18 years. [Source: Wikipedia]

White-lipped deer was discovered and named in the West in 1883 by Nikolay Przhevalsky (1839-1888), the famed Russian geographer and explorer of Central and East Asia, who discovered and named several species, including the Przewalski horse during the later 1870s. W. G. Thorold later described the same deer, not knowing that it had already been described. He he named it Thorold's deer (Cervus thoroldi) in 1891.[Source: Pam Ehler, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List white-lipped deer are listed as Vulnerable; US Federal List: classifies them as Threatened. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. According to researchers studying in the Tibetan Plateau, numbers of white-lipped deer may on the rise. increasing. In surveys conducted in 1990-1992 and 1997 they observed 80-89 deer during September of 1997, up from only 16 in early 1990s.

White-lipped deer are mainly threatened by habitat loss, human encroachment, hunting and poaching. They have traditionally been hunted for food by Chinese and Tibetans and poached for their enormous antlers. The antlers and other body parts are used in traditionally medicines. Natural predators include snow leopards and gray wolves. White-lipped deer are herd animals and all members of the herd are on the alert for predators. These deer are fast and agile runners and can defend themselves with their sharp hooves. Females attempt to distract predators from their young by causing a disturbance and running away from where the fawn is hidden.

White-Lipped Deer Characteristics and Diet

White-lipped deer are one of the largest members of the deer family. They weigh from 130 to 140 kilograms (286 to 308 pounds) and have a head and body length that ranges from 190 to 200 centimeters (74.8 to 78.7 inches). Unlike other deer species they have broad rounded hooves much like those of a cow. These hooves are specialized for climbing on steep, rough terrain. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Ornamentation is different. Females have a tuft of hair between their narrow, lance shaped ears. The five to six pointed antler rack of males protrudes forward and is flattened, like those of caribou. The white colored (rarely light brown) rack can weigh up to seven kilograms and reach l.3 meters. [Source: Pam Ehler, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=] /=\

As their name implies, white-lipped deer have a characteristic pure white marking around their mouth and on the underside of the throat. The inner side of the legs and the underside of the body are also whitish in color. The coloration on most their body is dark brown during the summer and lighter during the winter. Their fur is thick and course and lacks the undercoat hairs, which are usually among deer found in cold climates. A saddle-like image is present on the center of the deer's back, This is caused by the hair lying in the opposite direction. The fur coat is twice as long in the winter as it is during the summer.

White-lipped deer are exclusively herbivorous. They graze primarily on grasses — mainly Stipa, Kobresia, and Carex spp. — sedges and herbs. but also eat leaves, wood, bark, stems and tender sprouts. These deer mainly search for food in the morning and evening but can graze throughout the day.

White-Lipped Deer Behavior and Reproduction

White-lipped deer are cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). They sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. [Source: Pam Ehler, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

White-lipped deer are most active during the day. They are good at climbing in the rough terrian of their native habitat which includes many crags and cliffs and is largely in remote areas beyond human influence. White-lipped deer live in herds and move vertically in accordance with the season. They travel in groups separated by gender and age much like red deer. Juvenile males travel as one small group. Females who are pregnant, those still nursing their young, and pre-adult females travel in another group. Older males travel alone. During the mating season mixed-sex groups occur. When necessary, these deer hide themselves in the shrubbery on the edge of a forest.

White-lipped deer are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding — breeding once yearly, in October and November. The number of offspring ranges from one to two, with the average number of offspring being one. The gestation period ranges from 7.67 to 8.33 months. The average weaning age is 10 months. On average females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 15 months.

After spending most of the year in separate herds, males and females come together during the breeding season, or rut. Mixed herds with between 50 and 300 deer have been reported at the peak of the mating season. Males compete amongst themselves during the breeding season for access to females and expend large amounts of energy n mating and aggressive male-male encounters. Most males lose weight during this period.

White-lipped deer are born from May through late June. The well developed young are able to stand only a half hour after birth, stay and travel with their mothers in female herds. Two to three days after birth, the mother takes her fawn into a more sheltered area away from the birth place. The baby is left to rest at times but is never out of the mother's sight. If she sees that something is near the baby, the mother will attempt to cause a distraction by running in the opposite direction. Fawns stay with their mother for about 10 months when they are weaned. At that time fawns joins the sex-segregated herds. Young males move to the male herd, young females stay in the herd in which they were raised and travel with their mothers, though they are no longer dependent upon them.

Tibetan Horses

In 1993, French anthropologist Michel Peissel discovered a breed of domesticated horse in the remote Nangchen region of Tibet which is believed to be new to science. Free of the Arabian, Mongolian and Turkish horse blood, which is found in nearly every other horse in the world today, the Tibetan horse was raised by nomad horsemen in valleys that were so remote the horses were prevented from mixing with other types of horses for thousands of years.

"Unlike the Mongolian horse, which is free range," Peissel told the New York Times, "the Nangchen only survives due to constant human intervention and selection. Free range horses that breed on their own don't achieve the degree of physical perfection and stamina found in horses selectively raised by man." As an adaptation to the high altitudes the Tibetan horse has an enormous heart and massive lungs. The animals are used for herding livestock and competing in horse races at important three-week festivals.

In 1995, Peissel discovered a new breed of wild horse in the Riwoqe region of northeastern Tibet after his expedition was forced to change its route because of a snowstorm and pass through an isolated valley with unmapped forests. Similar to horses depicted in Stone Age paintings in European caves, the Riwoqe horse is short and squat and looks more like a donkey than a horse. It stands about 3.5 feet tall and has tiny ears, small nostrils, a dark bristly main, a brown coat and black lines on its back and lower legs.

Riwoqe horses live in a valley hemmed in by 16,000 foot passes. Scientists suggest that they may be members of a "relic population" isolated from other horses and able to keep its unique characteristics. "They looked completely archaic," Peissel told the New York Times, "like horses in prehistoric cave paintings. We thought it was just a freak then we saw they were all alike." Describing the expedition in which the horse was discovered (his 24th in the Himalayas) Peissel said, "It was very bleak. We had to cope with hailstorms and trek along precarious trails with very steep drops. I think it was the most difficult journey I ever made."

Kiang (Tibetan Wild Asses)

Kiangs (Equus kiang) are the largest of Asia’s wild asses. Also known as Tibetan wild asses, they live at elevations of 4,000 to 7,000 meters (13,125 to 22965 feet) and have black manes and tan-and-white bodies. Their numbers were greatly reduced in the 1960s when Chinese soldiers shot them for sport and for food. They and Tibetan gazelles are increasingly having to share their habitats with livestock. The number wild asses has grown to 200,000 in recent years and this is viewed as a modest conservation success story. Some complain that kiang are becoming pests as they compete with the livestock for what is left of the grasslands. [Source: Jonathan Watt, The Guardian, June 15, 2010]

Kiang are wildly distributed in Tibet, Qinghai and Sichuan regions of China and are also found in the Himalayan and high plateau areas of Nepal, and India. They are found mainly in alpine grass lands and prefer dry open areas including desert, semidesert, or steppe. Annual precipitation the areas where they are found in generally minimal. Three subspecies have been identified largely based on different populations in different areas, but these designations are still debated. controversial. It is estimated that they live about 20 years in the wild. Their average lifespan in captivity is 30.1 years. [Source: Hui-Yu Wang, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List kiang are listed as a species of Least Concern. They have traditionally been are hunted for meat and for their skins, which have been used in making leather. The main threats to kiang populations are habitat loss and competition for food sources from livestock. In some areas, poaching is still an issue. Only gray wolves prey on wild asses. They are too bog for snow leopards.

See Separate Articles: ONAGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Kiang Characteristics, Behavior and Reproduction

Kiang are the largest wild asses in the world. They range in weight from 250 to 440 kilograms (550 to 970 pounds). Their average length is 2.10 meters (6.9 feet). They stand about 1.4 meters (4.6 feet) at the shoulder and have a tail lengths of about 50 centimeters. Their fur changes with season — from short, thin and reddish in summer to long, thick and dark brown in winter. Kiang look more like horses than asses because of their short ears and large tail tufts. They are very similar to onagers (Equus hemionus) genetically and physically. The mitochondrial DNA divergence between the two species is only one percent, and the divergence probably arose less than 500,000 years ago. Kiang running speed is slightly slower than onagers. Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present in kiang: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar.

Kiang are nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), colonial (live together in groups or in close proximity to each other), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). They sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell and are good swimmers. During summer they are often observed bathing in rivers. Kiang usually form family groups of five to 400 animals. Such groups are led by an old female, and very cohesive, often travelling long distances together in search of food. /=\

Kiang are primarily herbivores (primarily eat plants or plants parts), and are also classified as folivores (eat leaves). They feed primarily at night. Among the plant foods they eat are leaves. grasses and stubby plants. They are especially fond on forbs ( a herbaceous flowering plants) such as Stipa spp., which are widely distributed and plentiful. Their feeding areas sometimes overlap with those of domestic sheep during summer. Kiang may gain 40-45 kilograms during the vegetation growth season in August to September. /=\

Kiang are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding. The breeding season is August-September. Males mob females and guard them from rival males. Single males follow the female herds and fight for breeding rights. The average number of offspring is one. The average gestation period is 12 months and the average weaning age is 12 months. Parental care is provided by females. Young are precocial. This means they are relatively well-developed when born. They are usually born in late July to August when food is plentiful and can walk a few hours after birth. On average females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at two years.

Tibetan Foxes

Tibetan foxes (Vulpes ferrilata) are also known as Tibetan sand foxes. They are a species of true fox that live in the high Tibetan Plateau, China, Bhutan, the Mustang area of Nepal and Ladakh, Sikkim and Sutlej valley of northwestern India up to elevations of about 5,300 meters (17,400 ft). Tibetan foxes inhabit barren slopes and streambeds and appear to prefer rocky or brushy areas at high elevation. They often sleep and rest in excavated dens or burrows under rocks or in crevices of boulder piles. Their lifespan in the wild is five to 10 years.[Source: Melissa Borgwat, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, Tibetan foxes are listed as a species of Least Concern as they appear to be widespread in their range in the Tibetan Plateau's steppes and semi-deserts. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they have no special status. The only known predators of Tibetan foxes are humans. When threatened, Tibetan foxes retreat to their dens. (Nowak, 1991; Schaller, May 2000) /=\

Tibetan foxes are primarily carnivores and mostly eat terrestrial vertebrates such as mammals and birds as well as eggs. Foxes often hunt in pairs (one male, one female) and share whatever food is caught. They primarily hunt rodents, hares, rabbits, and small ground birds. However, anything that can be caught will be eaten. The black lipped pika, which shares much of their range and habitat, appears to be a preferred prey item. Tibetan foxes play a significant role in controlling the rodent and small animal population.

The only known predators of Tibetan foxes are humans, who commonly trap and kill them for their fur. The fur is used in Nepal and Tibet to make hats which are valued for protecting wearers from the wind and harsh cold. Some researchers believe the lifespan of these foxes is eight to ten years under ideal circumstances but many die as a result of natural causes or human hunters before they become five years old.

See Separate Article: FOXES factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Fox Characteristics, Behavior and Reproduction

Tibetan foxes range in weight from three to four kilograms (6.6 to 8.8 pounds) and range in length from 97.5 to 117.5 centimeters (38.4 to 46.7 inches). Their head and body length is 57.5 to 70 centimeters (22.6 to 27.5 inches). Their.tail is 40 to 47.5 centimeters (15.7 to 18.7 inches) long and their muzzle is elongated compared to most other fox species. The teeth are well developed and they possess extraordinarily long canines and narrow maxilla. Tibetan foxes range in color from black, to brown and rusty-colored, to yellowish on neck and back. They have a tawny band on their back side and white on the tail, muzzle and belly. The fur is thick, with a dense undercoat. [Source: Melissa Borgwat, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Tibetan foxes are terricolous (live on the ground), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and social. Mated pairs remain together for life. When one of the pair dies, it not known if the other seeks a new mate. Kits (young) stay with the parents until they are eight to 10 months old. At that age they leave the den to find mates and home ranges of their own. These foxes are not strongly territorial. Many pairs have been found living close to other pairs and sharing the same hunting grounds and they are not known to actively defend their area.

Tibetan foxes sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also leave scent marks to define territory produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. Short yips are one form of communication. Since pairs usually stay close together, no long distance communication is known or thought necessary. Scent is used to define territory.

Tibetan foxes are monogamous, with mated pairs staying together for life. They engage in seasonal breeding — breeding once a year in late February or early March. The gestation period ranges from 50 to 60 days. The number of offspring ranges from two to five. Males and females and share the responsibility of raising their young together. Kits are born in late April to early May. All canid young are altricial (born helpless and requiring significant parental care). During the pre-birth and pre-weaning stages provisioning is done by females and protecting is done by males and females. During the pre-independence stage provisioning and protecting are done by males and females Kits do not emerge from their natal dens until they are several weeks old but develop quickly and within eight to ten months are sexually mature. There is an extended period of juvenile learning. /=\

Tibetan Snow Frog

The snow frog, also known as the Chinese forest frog, lives in the mountain, forests and swamps of Tibet. It is born in the spring and fall and hibernates in the winter. It is a very valuable frog to Tibetans not only because its meat is as delicate as chicken, also because it is rich in protein and calcium and has little fat. As the meat of the frog is sweet, cool, intoxicating and rich in moisture, it is regarded as an exotic dish in Tibet. [Source: Explore Tibet]

The snow frog has been used in Tibetan medicine for hundreds of years as a treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis and impotence. In addition, it has the functions of clearing heat, improving vision and nutrition. The snow frog is a cold blooded creature whose temperature is never much higher than its environment. It also frog has the ability to change its colors according to the habitat they occupy. Like others of their kind, frogs are recognized as being exceptional jumpers. Female snow frogs are usually larger than males.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Cosmic Harmony, Purdue University

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025