PIKAS

Pikas are small, mostly mountain-dwelling mammal native to Asia and North America, with most of the 30 species in Asia. They have short limbs, very round bodies, even coats of fur, and no external tail. They resemble their close relatives rabbit, but have short, rounded ears. Typically, pikas live for only a few years in the wild and many pikas do not live through their first winter.

Pikas are among the highest-dwelling mammals. They have been observed on high slopes of Mt. Everest. According to the Guinness Book of Records in the 1980s, they were the highest living animal in the world. A pika has been observed at an elevation of 6,130 meters (20,113 feet). Now, the yellow-rumped leaf-eared mouse is recognized as highest living animal. It has has been documented living at 6,740 meters (22,110 feet) in the Andes Mountains of northern Chile. This mouse species is a small, long-tailed rodent with unique adaptations to the high-altitude environment.

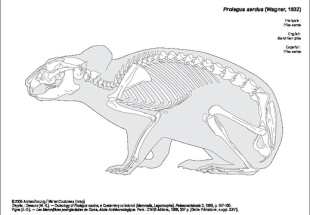

Pikas belong to the family of Ochotonidae, of which more than 30 extinct genera that have been identified as far back as the Eocene Period (56 million to 33.9 million years ago), one of which, Prolagus, went extinct in the late 18th century. Ancestors of modern ochotona emerged in the fossil record in the Late Miocene Period (11.6 million to 5.3 million years ago) in central Asia. Today, Ochotonidae make up a third of lagomorphs, the mammalian order that also includes rabbits and hares. The only two modern species that live outside Asia are American pikas and collared pikas which live in North America. [Source: Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

In English, pika is translated as “whistling hare.” The name pika is derived from the Tungus word pika and the scientific name Ochotona is derived from the Mongolian word ogotno, which means pika. According to Encyclopædia Britannica: “Despite their small size, body shape, and round ears, pikas are not rodents but the smallest representatives of the lagomorphs. Pikas range in weight from 70 to 300 grams (2.5 to 10.6 ounces) and are usually less than 28.5 centimeters (11.2 inches) in length. Sexual dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present. Both sexes look the same and are the same size. The differ from leporids (hares and rabbits) in that they are smaller in size and lack supraorbital processes (bony extensions above the eye sockets (orbits) of the skull) and have small, rounded ears, concealed tails, and two. rather than three upper molars.

Ochotonidae is one of two families in the order Lagomorpha. The other is Leporidae (rabbits and hares). Lagomorpha and Rodentia make up the clade Glires. Glires and Archonta make up the clade Euarchontaglires. Ochotonidae was first described in 1897 by Oldfield Thomas. Relationships within the Ochotonidae family and within the genus Ochotona are not well understood. Molecular phylogenies have been done by Yu et al. (2000), Niu et al. (2004), Lissovsky et al. (2007), and Lanier and Olson (2009). Current understanding is that there are three subgenera within Ochotona based on both morphological and molecular evidence. The relationships between these and the independence of some species is still highly debated. /=\

The name pikachu is not derived from the pikas, the animals, although both are very cute. Pikachu is derived from a combination of two Japanese onomatopoeia (words from a sounds): (pika), a sparkling sound, and (chū), a sound a mouse makes.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PIKAS IN CENTRAL ASIA, MONGOLIA AND RUSSIA factsanddetails.com ;

PIKAS IN CHINA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, RANGES factsanddetails.com

PIKAS IN TIBET AND THE HIMALAYAS factsanddetails.com

LARGE-EARED PIKAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION

factsanddetails.com

PLATEAU PIKAS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, POISONING factsanddetails.com

Ili Pika Under ENDANGERED ANIMALS IN CHINA: BEARS, WILD CATS AND RIVER DOLPHINS factsanddetails.com

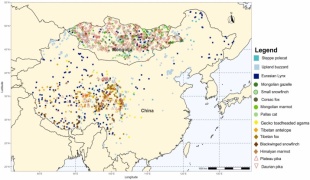

Pika Range, Habitat and Ecotypes

Although the historic range of pikas included Asia, Europe, northern Africa, and North America, today nearly all pikas are found in Asia. China is home to greatest pika diversity, with more than two dozen species there. In Asia, pikas are found as far west as Iran, as far south as India and Myanmar, and as far north as northern Russia. The two Nearctic species are found in the central Alaskan Range, the Canadian Rockies, and the Rockies, Sierra Nevadas, and Great Basin in North America. [Source: Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

There are two main pika ecotypes: talus-dwelling ones that live mainly in rocky habitats and meadow-dwelling ones which reside mainly in meadow, steppe, forest, and shrub habitats. Each ecotype is associated with specific life history traits as well as behavior. Most species fall within one of these ecotypes, although there are some species which exhibit intermediate characteristics. The average mortality of talus-dwelling species is low and many are relatively long- lived compared to other small mammals. For example, American pikas live on average three to four years but have been known to live up to seven years. Meadow-dwelling species experience have high annual mortality as many are prey for animals such as foxes and wolves and few live more than two years. /=\

Talus-dwelling pikas inhabit the crevices between rocks on mountain slopes. They like rocky mountainsides, where numerous crevices are available for shelter and forage in the alpine meadows that abut the rocks or from the vegetation that grows between the rocks. They are found across a wide altitudinal range from below 90 meters to above 6000 meters (20,000 feet). Among the talus-dwellers are Himalayan pikas, alpine pikas, collared pikas, silver pikas, Glover’s pikas, Chinese red pikas, northern pikas, Ili pikas, large-eared pikas, Royle’s pikas, Turkestan red pikas and American pikas. /=\

Meadow dwelling pikas are found in a variety of vegetated habitats where they forage and produce burrows. The meadows they occupy are also typically at high elevation. Among these are steppe pikas, black-lipped pikas, Gansu pikas, Kozlov’s pikas,, Daurian pikas, Muli pikas, Nubra pikas, Ladakh pikas Moupin pikas, and Thomas’s pikas. Some species, including Pallas's pikas and Afghan pikas are known to occur in both habitat types and are referred to as intermediate species. Although intermediate in habitat, these species exhibit the life-history traits and behavior of meadow-dwelling pikas. /=\

Talus-dwelling pikas are known for being asocial and territorial. It has been hypothosized that the length of vibrissae and the shape and thickness of claws can distinguish talus-dwelling pikas from burrowing pikas. Talus-dwelling pikas are believed to have longer vibrissae while burrowing meadow pikas have straighter, more powerful claws. [Source: Anna Maguire, Animal Diversity Web]

Pika Characteristics

Pikas are remarkably uniform in their body proportions and postures. All pikas have short silky fur, short rotund ears and a short neck relative to body size that supports a large globular head with large black eyes. Their fur is long and soft and is generally grayish-brown in color, although some are rusty red. Unlike rabbits and hares, their hind limbs are not significantly longer than the forelimbs — the traits that allows rabbits and hares to hop and move they way they do. Physiologically, pikas have a high metabolic rate. They also have low thermal conductance and, even at moderately high temperatures, low ability to dissipate heat. Most pikas live in places that are cold much of the year.

Pikas are generally small, ranging in body length from 12.5 to 30 centimeters (4.9 to 11.8 inches) and weigh 70 to 300 grams (2.5 to 10.6 ounces). Some have short tails. Whether internal or external their tail has eight vertebrate. Pikas have large, valvular flaps and openings at the level of the skull. Their ears can move only a little and their nostrils can be completely closed. Their hind limbs are only slightly longer than the forelimbs. They have five digits on their front paws and four on their hind paws, all with curved claws. The soles of the feet are covered by long hair but the distal pads are exposed. The burrowing pikas have longer and stronger claws, relative to talus-dwelling pikas. they also has shorter whiskers than the talus-dwelling species of pika. They run on their toes without touching their heels to the ground but touch their soles to the ground when moving slowly. [Source: Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Pikas have 22 thoracolumbar vertebrae and lack a pubic symphysis. The skull is generally similar to that of leporids. It is flattened, exhibits fenestration, and is constricted between the orbits. The pika tooth formula is 2/1 0/0 3/2 2/3=26. The first incisors are ever-growing and completely enameled, while the second are small, peg-like, and directly behind the first. The cutting edge of the first incisor is v-shaped. They have a long post-incisor diastema and hypsodont, rootless cheek teeth. Occlusion is limited to one side at a time, with associated large masseter and pterygoideus muscles allowing for transverse movement while the cheekteeth have transverse ridges and basins. The zygomatic arch is slender and not vertically expanded. The jugal is long and projects more than halfway from the zygomatic root of the squamosal to the external auditory meatus. Unlike leporids, pikas lack a supraorbital process. Their rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth) is short and narrow and the maxilla has a single large fenestra. The auditory bulla, which is fused with the petrosal, are spongiose and porous. The bony auditory meatus is laterally directed and not strongly tubular. /=\

Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not present: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar.. Males lack a scrotum and both sexes have a cloaca, which opens on a mobile apex supported by a rod of tail vertebrae. Females have between four and six mammae, with one pair in the groun area and one to two pairs on the chest area. Pika have long, dense, fine fur. Some pikas go through two molts, with darker fur in the summer and grayer fur in the winter. /=\

Pika Eating Habits and Diet

Pikas are generalist herbivores and typically collect and store caches of vegetation, which they live off of during the winter. They consume leaves and stems of forbs (herbaceous flowering plants) and shrubs as well as seeds and leaves of grasses, Sometimes they also consume small amounts of animal matter. Collared pikas have been known to store dead birds in their burrows for food during winter and eat the feces of other animals. Like most leporids, they produce two types of feces: soft caecotroph and hard pellets. [Source: Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

During the summer, after the breeding season, pikas accumulate large stores of many different plants in their caches, sometimes called haypiles, which are eaten during for winter. Hay-curing occurs when pikas gather grasses, sedges, weeds, and many woody plants in the late summer and lay them out on rocks to be dried in the sun. These piles are then stored at the entrances to pika burrows.

Their foraging habits vary throughout the season according to what plants are available, selecting those with the highest nutritional, caloric, lipid, water, and protein content. In the autumn, they pull hay, soft twigs, and other stores of food under rocks to eat during the long, cold winter. Pikas prefer foraging in temperatures below 25 °C (77 °F)., so they generally spend their time in shaded regions and out of direct sunlight when temperatures are high. Pikas are most active just before the winter season when they collect hay, soft twigs, and other foods and put them under rocks or in their burrows — a process sometimes called haying — to eat during the long, cold winter..

The foraging habits of pikas can affect plant communities. Pikas alter which plants are collected while foraging as well as how far they go to forage, depending on whether they are being immediately consumed or are being added to their cache. This variation results in a mosaic of plant community composition — a process that has been demonstrated to stabilize plant community composition and slow the process of succession, as well as reduce the number of seeds in the soil. /=\

Lagomorpha Feeding, Digestion and Poop-Eating

Lagomorpha — hares, rabbits and pikas — are coprophagous (eat dung) and have two pairs of sharp, chisel-like incisors (rodents have only one pair) that grow continuously. These are used to chop off grasses and other vegetation with a distinctive, clean, angled stroke. Most lagomorphs are completely vegetarian, and have evolved a unique system for extracting the maximum nutritional value from coarse plants. The food is first passed through their digestive system and discharged as soft feces. Pikas, rabbits and hares eat these, These are then reingested and passed through again, emerging as the dry round pellets that you see in clusters all over their feeding grounds. The way lagomorpha digest leaves thus involves eating their own droppings., When they are asleep in their burrows at night they excrete black sticky pellets from their anus. These are consumed to go through a second round of digestive processing. The second round are excreted outside the den after the lagomorpha wakes up.

Lagomorphas are gnawing animals like rats, mice and squirrels. They have sensitive hearing and smell. Lagomorpha food such as grass and leafy weeds is high in cellulose and difficult to digest. Chewed plant material collect in an area of the digestive tract called the cecum, The cecum contains bacterial colonies that partly break the cellulose down. When the soft feces are ingested they are eaten whole and digested in a special part of the stomach, If they only ate their food once they wouldn’t absorb enough nutrients.

Lagomorphas often feed at night—which is why most people with pet lagomorphas have never seen them eat their poop—and stay in their nests during the day. Northern pikas defecate small green droppings, typically during the day. At night, they defecate black droppings which are often encased in a gelatinous substance. The black droppings have higher energy values and are reingested. [Source: Allison O'Brien, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Pika Behavior

Pikas are terricolous (live on the ground), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), territorial (defend an area within the home range), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Pikas do not hibernate during the winter. Instead stay active in their burrows or rocky crevices, which tend to be warmer than outside. During this time they consume the food cached away during the summer. Pikas are primarily diurnal, but can be active at all times of day as well as throughout the year. They are frequently observed sunning themselves on rocks during warmer months [Source: Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Pikas usually do not range far from their natal territory. Among talus-dwellers, individuals with control of a territory typically maintains it for life, and upon death are replaced by a juvenile born in a nearby territory usually of the same sex. Among meadow-dwellers, juveniles stay in their home burrow for the first year. Then, less than half disperse to nearby territories. Males are more likely to disperse, but they don’t go far, then typically move only a few territories away. /=\

For most pikas their home range consists of their burrow or nest and an area of land that surrounds it. Most social behavior is related to reproduction or family. Male pikas typically only have interaction with other males involving territorial disputes. Males and females usually on interact during breeding season. Pikas are noted for collecting vegetation from their immediate area and piling it up into a hay pile in their burrow. They use this burrow as stored food for over the winter when food is scare in the cold harsh climates of northern Asia. [Source: Jon Kiefer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The behavior of pikas can be greatly affected by temperature. Pikas generally have relatively high body temperatures (40.1̊ C, 104.2̊F) and having a low tolerance to any increase in body temperature. As a result, pikas regulate their body temperature by changing behavior. During hot summer days, pikas may become inactive in order to minimize any increase in body temperature. . Pikas may also alter their home range to be close to cooler temperatures . [Source: Anna Maguire, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

During summer months and early fall, pikas busily collect food for the winter. Red pikas have been observed adding plants to their hay stacks 20 to 30 times per hour. During winter months, pikas do not hibernate but may decrease their activity levels. During this time they rely strongly on their hay-stacks for food.

Behavior Difference of Talus-Dwelling and Meadow-Living Pikas

The talus-dwelling pikas in North America occupy and defend territories individually, particularly against members of the same sex. Except for when they come together to mate, these are relatively asocial. Dominance does not extend beyond an individual’s territory. Most social interactions are aggressive. Chases and fights as a result of intrusion, and the theft of vegetation from the haypiles of members of their own species. Territories are usually established near the edge of talus–vegetation borders and vary in size depending on species and the amount of food resources available They are typically between 450 and 525 square meters (4,843 and 5,651 square feet). [Source: Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Some Asian talus-dwelling pika species defend territories as pairs. The pair uses the same main shelter and spend most of their time in the same area. They cooperate in hay-storage and communicate using vocalizations, but are asocial outside of the pair. Primarily the males demarcate the territory and defend it against intruders. These territories are typically larger than those of individual pikas, around 900 square meters (9,687 square feet) per pair, and these pikas live in much higher densities. /=\

In contrast, Asian meadow-dwelling species are more social. Social family groups consist of adults as well as young of the year in communal burrows. These species live at much higher densities (more than 300 per hectare) than the talus-dwelling species and experience more variation in population density over seasons and between years. Meadow-dwelling pikas are more likely to exhibit social behaviors, such as allogrooming, nose rubbing, and various forms of contact, within family groups, as well as aggressive territorial behaviors toward non-family members. They also defend territories as a family unit and share communal hay piles. Their territories are also demarcated by scent-marking and vocalizations. /=\

Pika Communication and Calls

Pikas sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound, vibrations and chemicals usually detected by smelling and scent marks (produced by special glands and placed so others can smell or taste them). Pikas use scent marks to define their territory to keep other pikas away. Pikas can recognize individuals based on the scent an individual gives off by the scent glands on its' cheeks [Source: Jon Kiefer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Meadow-dwellers may communicate with vocalizations to affirm social bonds. Both Talus-dwellers and meadow-dwellers use scent-marking. Talus-dwelling pikas use vocalizations and scent-marking to demarcate their territories, which are relatively large and make up about half of their home range. [Source: Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Pikas are sometimes called whistling hares because of their high-pitched alarm calls they make when alarmed. Most pika species vocalize to warn of predators and to defend their territory. . Their high-pitched 'eek' or 'kie' vocalizations have ben described as being ventriloquial in character. They have also been observed eavesdropping on the alarm calls of marmots and ground squirrels. Pikas sometimes communicate danger by drumming on the ground with their hind feet. Meadow-dwelling, burrowing species produce many types of vocalizations, many of which are used in socializing with members of their group. Low chattering and mewing noises have been reported.

Pika species emit various types of calls that serve different purposes such as mate solicitation, alarm calls and territorial calls. The calls, can vary in duration. Some are short and quick; other are little longer and more drawn out. There are also long songs. Short short calls can used in geographic orientation. Pikas determine the appropriate time to make short calls by listening for cues for sound localization. The calls are used for individual recognition, predator warning signals, territory defense, or as a way to attract potential mates. There are also different calls depending on the season. In the spring the songs become more frequent during the breeding season. In late summer the vocalizations become short calls. Through various studies, the acoustic characteristics of the vocalizations can be a useful taxonomic tool in determining different species. [Source: Wikipedia]

Pika Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Pikas can be monogamous (having one mate at a time), polyandrous (with females mating with several males during one breeding season), polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time), or polygynandrous (with both males and females having multiple partners)\ Most talus-dwelling pika species are monogamous or polygynous, with some exceptions, including documented cases of polygynandry in collared pikas. In contrast, meadow-dwelling pikas can be monogamous, polygynous, polyandrous, or polygynandrous depending on the sex ratio at the beginning of the breeding season. [Source: Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Pika young are altricial. This means that young are born relatively underdeveloped and are unable to feed or care for themselves or move independently for a period of time after birth. Parental care is provided by both females and males. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. Young may inherit the territory of their parents, mother or father. /=\

Pikas engage in seasonal breeding. The breeding season for American pikas lasts between late April and the end of July. Their gestation period is 30.5 days. Typically, talus-dwelling pikas produce only one successfully weaned litter of one to five young a year. On average, approximately two young per mother are successfully weaned per year. Juveniles reach sexual maturity as yearlings. Some talus-dwelling species exhibit absentee maternal care typical of lagomorphs.

Talus-dwelling pikas characteristically have a low reproduction rate and give birth to smaller litters than meadow-dwelling pikas. According to Animal Diversity Web: Meadow-dwelling species have much higher potential reproductive output, but it varies depending on environmental conditions. They can produce litters that are twice as large as those of talus-dwellers up to every three weeks during the reproductive season. The reproductive season of plateau pikas, a meadow-dwelling species, generally lasts from March to late August but can vary between years and sites. On average, multiple litters are produced each year and most young are successfully weaned. Further increasing their reproductive output, juveniles born early in the breeding season will reach sexual maturity and breed during the summer of their birth. Males and females of some meadow-dwelling species participate in affiliative behavior with juveniles as well as mate guarding and defending territories (e.g. Smith and Gao, 1991). Juveniles of meadow-dwelling species also continue to live on the parental territory through at least their first year. /=\

Pikas, Predators and Ecosystems

Pikas, particularly meadow-dwelling ones, are an important food source for a number of carnivorous mammals and birds, including wolves, fozes, polecats, weasels, brown bears, Asiatic black bears, hawks, eagles, buzzards and owls. [Source: Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Meadow-dwelling pikas can be eaten throughout the year, but are especially important prey in the winter as they are still active while similarly-sized rodents hibernate. During high-density years, burrowing pikas are often primary food source for Asian steppe predators, sometimes making up more than 80 percent of their diet. Pikas are consumed by both small to medium-sized carnivores such as weasels and foxes and larger carnivores, including wolves and brown bears.

Pikas are a keystone species, meaning their presence or absence strongly affects populations of other species in area where they live. They help aerate soil and serve as consumers and as prey. They can alter their environments through bioturbative ecosystem engineering. The burrowing of meadow-dwelling pikas improves soil quality and reduces erosion. The accumulation and decomposition of leftover caches and their feces in burrow systems fertilizes and helps increase the organic content of soil. Pika burrows provide homes for other animals and their caches can be consumed by other herbivores. The haypiles of talus-dwelling pikas help create and improve soil, thereby helping plants to grow in areas otherwise dominated by rocks. /=\

Humans and Ecosystem Roles of Pikas

Traditionally, pikas were a valuable sources of fur throughout Asia, particularly in the the Soviet Union, and traditional pastorialists selectively grazed their livestock in the winter on pika meadows where haypiles are exposed above the snow. Human activities and settlements can have impacts on pikas. When pikas mistake humans for predators, they may respond as they do to species that do prey on them by escaping to their rock crevices or burrows. Such interactions with humans have been linked to pikas having reduced amounts of foraging time, consequentially limiting the amount of food they can stockpile for winter months. [Sources: Wikipedia, Aspen Reese, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

In some places pikas are considered pests as it it is believed that they compete with livestock for forage, erode soil, and have a negative impact on agricultural crops such as apples and grain. It has been demonstrated that pikas can harm some agricultural crops but no control studies have been conducted that support other claims. Pika foraging has blamed for accelerating range deterioration but only in areas that were already overgrazed. Poisons have been released on millions of hectares of grazing land in efforts to control pika numbers with debatable results, including extermination of non-target species and poisoning of predators that prey on pikas. .

In some places pikas and livestock do feed on the same vegetation and thus effectively compete against one another. One study of a pika species in Mongolia concluded that the competition between pikas and livestock reduces the potential population numbers of both groups. As both pikas and livestock eat the same vegetation they can also significantly reduce the prevalence of preferred plant species and allow other non palatable species to grow and out compete the preferred vegetation. [Source: Jon Kiefer, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

However, pikas, particularly burrowing ones, can play an important role in nutrient recycling in their habitats by making haypiles in their burrows. Pikas can accumulate large amounts of vegetation within a single hay pile and as that pile decomposes it contributes to the direct recycling of nutrients in plant biomass to the top soil. There is some evidence that these decomposing hay piles also increase the productivity and biomass on the plants in the soil above them. The act of digging up soil to make their burrows helps loosen and aerate the soil which can increase plant productivity and increased water infiltration. Pika burrows are extremely stable and can hold up for multiple years without regular maintenance.

Endangered Pikas

Four pika species (silver pikas, Hoffmann's pikas, Ili pikas, Kozlov's pikas) are classified as endangered or critically endangered due to habitat loss, poisoning, or climate change. Due to their low tolerance for high temperatures and low vagility, pikas are considered especially vulnerable to climate change. Changing temperatures have already forced some pika populations to move to higher elevations. Pikas prefer foraging in temperatures below 25 °C (77 °F). A correlation has also been found between temperature increases and lost foraging time, where an increase of 1 °C (1.8 °F) to the ambient temperature in high-altitude regions results in pikas losing three percent of their foraging time.

Not enough is known about many pika species (10 percent are still considered data deficient by the IUCN) to make accurate assessments of their populations and number to evaluate conservation status. Several subspecies are threatened by low vagility (the ability to move around freely and migrate) due to human settlements and fencing, and their impacts on stochastic metapopulation dynamics — how random, unpredictable events (stochasticity) influence the persistence and structure of metapopulations, which are groups of local populations connected by dispersal.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025