YAKS

Yaks are cattle-like animals about the size of small oxen. Adapted for living at high altitudes, they have long hair that hangs off their sides like a curtain, sometimes touching the ground. Underneath is a soft undercoat that keeps the animal warm in the coldest and windiest environments. Yaks are highly valued by Himalayan peoples. They may have been domesticated in Tibet in the first millennium B.C.. According to Tibetan legend, the first yaks were domesticated by Tibetan Buddhism founder Guru Rinpoche.

Yaks are cattle-like animals about the size of small oxen. Adapted for living at high altitudes, they have long hair that hangs off their sides like a curtain, sometimes touching the ground. Underneath is a soft undercoat that keeps the animal warm in the coldest and windiest environments. Yaks are highly valued by Himalayan peoples. They may have been domesticated in Tibet in the first millennium B.C.. According to Tibetan legend, the first yaks were domesticated by Tibetan Buddhism founder Guru Rinpoche.

Yaks are essential to life in the Himalayas and the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Docile yet powerful, they are the most useful domestic mammals at high elevations. They serve as mounts, beasts of burden, and provide milk, meat and wool and have no problem living in terrain elevations up to 6,500 meters. Tibetan Yaks were formerly ranched and used for transporting goods. Today with highways, trucks and modern agricultural equipment, yaks are rarely used as work animals any more. Instead, they are raised for wool, milk and meat.

Yaks are built to survive in tough environments. They are around 3.3 meters (11 feet) in length, not including their 60 centimeter tail, and stand up to two meters at the shoulder. Their long, thick hair insulates their bodies from winter temperatures that can get to -30C (-22F) or colder. Yaks weigh up to 525 kilograms (1,160 pounds). Their horns may reach 95 centimeters (38 inches) in length. Females tend to be smaller than males. Most yaks are black, but it is not uncommon to see white or gray ones especially on the grasslands of northern Amdo (modern day Qinghai province).

The Chinese word for yak is "mao niu," or "hairy cow." The generic Tibetan name of the animals means "wealth" or “jewels that grant all your wishes.” Technically, only castrated males are yaks. Bulls are “boas” and cows are “dris”. Mostly what tourist see are “dzos” or “dzomos” — yak and cow crossbreeds. Dzos are used as pack animals at lower elevation than yaks. They also produce milk, butter and cheese.

Of the 14 million or so domesticated yaks and yak hybrids in the world, some sources say, about five million live on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. According to Chinese estimates 85 percent (or about 10 million) of the world's yaks live on the Tibetan Plateau. Domesticated yaks have long horns, hairy tails that sometimes have white tips and humps behind their head that looks bigger than they actually are because of a thick mat of hair. Yaks rarely exceed five feet in height at the shoulder. They look bigger than they are because of all their hair.

Good Websites and Sources: China.org article on Tibetan animals china.org.cn ; Animalinfo.org on yaks animalinfo.org ; Wikipedia article on Yaks Wikipedia ; Life on Tibetan Plateau kekexili.typepad.com

THE YAK: SECOND EDITION, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2003 fao.org ; articles under TIBETAN NATURE factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN ANIMALS AND PLANTS factsanddetails.com ; SNOW LEOPARDS Factsanddetails.com/China ; SHAHTOOSH AND CHIRUS Factsanddetails.com/China ; TIBETAN NOMADS Factsanddetails.com/China

<

p class="linkbox"> RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Yak Husbandry” by Goutam Mondal and Roy B. Brahma Amazon.com; “Agro-Animal Resources of Higher Himalayas” by Deepa H. Dwivedi & SAnjai K. Dwivedi & Sandhya Gupta Amazon.com ;

“Yak Girl: Growing Up in the Remote Dolpo Region of Nepal”

by Dorje Dolma Amazon.com;

“Yaks” by Willow Clark Amazon.com

Wild Yaks

Wild yaks (Bos grunniens) are called drongs in Tibetan. They are up 3.25 meters (10.6 feet) in length and weigh between 305 and 820 kilograms (672 to 1,808 pounds). They live in alpine tundra and cold desert regions at altitudes between 4,000 and 6,000 meters (13,124 and 19,685 feet). They are kept warm by a dense undercoat of soft, close-matted hair covered by generally dark brown to black outer hair. Wild yaks are very rare. Few non-Tibetans and not many Tibetans either have ever seen a wild yak. They live both as solitary individuals and in groups in windy, desolate, extremely cold steppes, mainly in the Kashmir and Leh areas of India and in Tibet and Qinghai in China.

Wild yaks are larger but thinner than domestic yaks. Males can weigh up to 1,000 kilograms and measure 1.8 meters at the shoulder. Wild yaks are mostly black or dark brown, with the exception of the fabled golden wild yak. They generally have long black hair and horns that come out the sides of their head and turn upwards. Drongs In northern Tibet reportedly weigh a ton and reach a length of almost four meters (12 feet) and have a horn span of one meter (three feet). Herds of drongs are docile but an individual drong will sometimes charge.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, wild yaks are listed as Vulnerable. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I under No special status. They are threatened by habitat loss, poaching, diseases introduced by live stock, interbreeding with domestic yaks, low fertility and inbreeding.

Fossil remains of wild yak ancestor date back to the Pleistocene period (2,6 million to 11,700 years ago). Over the past 10 000 years or so, the yak developed on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, which covers about 2.5 million square kilometers (970,000 square miles). Yaks have been domesticated for centuries. Sometimes they are left on their own in mountain pastures for so long they become semi-wild. [Source: FAO]

See Separate Article: WILD YAKS (DRONGS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Yaks and High Altitude

Yaks are most comfortable above 4,270 meters (14,000 feet). They climb to elevations of 6,100 meters (20,000) when foraging and usually don't descend any lower than 3,660 (12,000 feet). Nomads migrate between summer and winter pastures and live in valleys between 4,270 to 4,880 meters (16,000 feet high). They only other livestock found at this elevation are sheep and goats.

Yaks are most comfortable above 4,270 meters (14,000 feet). They climb to elevations of 6,100 meters (20,000) when foraging and usually don't descend any lower than 3,660 (12,000 feet). Nomads migrate between summer and winter pastures and live in valleys between 4,270 to 4,880 meters (16,000 feet high). They only other livestock found at this elevation are sheep and goats.

Yaks are built to survive in an environment with little oxygen or forage. Their lungs are surrounded by 14 or 15 pairs of ribs — compared to 13 for cattle — and they act sort of like accordion baffles to help yaks inhale and exhale, in the process creating the grunting noises associated with yaks. Yaks have three times more red blood cells than normal cows and these cells are half the size of those of cattle, increasing their blood's capacity to carry oxygen and allowing to live without any problems on the high elevation grasslands of Tibet. Their thick coat and low number of sweat glands are also efficient adaptations for conserving heat. In winter, the yak survives temperatures as low as - 40 degrees C.[Source: chinaculture.org]

Herders don't like to sent their yaks below 12,000 feet because the are worried the animals will get malaria, parasites or other diseases. Descending below 9000 feet reportedly disrupts their breeding cycle. “Dhopa", a crossbreed hybrid produced from a yak cow (a nak) and bull, thrive better at lower elevations than yaks. The female offspring produces more milk than a nak but the male offspring bump into rocks more than the slow but reliable yaks.♬

Yak Characteristics, History and Behavior

Chloe Xin of Tibetravel.org wrote: “Yaks belong to the genus Bos, and are therefore closely related to cattle. Mitochondrial DNA analyses to determine the evolutionary history of yaks have been somewhat ambiguous. The yak may have diverged from cattle at any point between one and five million years ago, and there is some suggestion that it may be more closely related to bison than to the other members of its designated genus. Apparent close fossil relatives of the yak, such as Bos baikalensis, have been found in eastern Russia, suggesting a possible route by which yak-like ancestors of the modern American bison could have entered the America. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Yaks were likely the first creature to be domesticated by the Tibetan people and have lived in Tibet since the ancient time. Some Chinese experts believe that yaks were first domesticated in Tibet at least 3000 years ago. The species was originally designated as Bos grunniens ("grunting ox") by Linnaeus in 1766, but this name is now generally only considered to refer to the domesticated form of the animal, with Bos mutus ("mute ox") being the preferred name for the wild species.

Yaks are very sure-footed — even on narrow, step, rock-strewn trails with heavy loads on their back. They walk confidently through raging streams and along mountain paths with thousand-meter drops. but are notoriously slow and stubborn. They have thick woolly coats in the winter and shed much of their hair in the summer to prevent from overheating.

Yaks are gregarious and like to be in herds. They panic easily. If one yak panics often the whole herd follows suit. Herders sometimes purposely panic the lead yak so that herd acts as a snowplow and clears the way. Yaks generally sleep standing up. They have a square tongue and broad muzzle that allows them to forage close to the ground. They are better than other animals at diggong below icy snow to get grass. Some yaks spend so much time grazing on their own they become semi-wild.

Ruminants

Yaks are ruminants — cud-chewing mammals that have a distinctive digestive system designed to obtain nutrients from large amounts of nutrient-poor grass — and are members of the cow family. Ruminants evolved about 20 million years ago in North America and migrated from there to Europe and Asia and to a lesser extent South America, where they never became widespread. Cattle, sheep, goats, buffalo, deer, antelopes, giraffes, and their relatives are all ruminants.

Yaks are ruminants — cud-chewing mammals that have a distinctive digestive system designed to obtain nutrients from large amounts of nutrient-poor grass — and are members of the cow family. Ruminants evolved about 20 million years ago in North America and migrated from there to Europe and Asia and to a lesser extent South America, where they never became widespread. Cattle, sheep, goats, buffalo, deer, antelopes, giraffes, and their relatives are all ruminants.

As ruminants evolved they rose up on their toes and developed long legs. Their side toes shrunk while their central toes strengthened and the nails developed into hooves, which are extremely durable and excellent shock absorbers.

Ruminants chew a cud and have unique stomachs with four sections. They do no digest food as we do, with enzymes in the stomach breaking down the food into proteins, carbohydrates and fats that are absorbed in the intestines. Instead plant compounds are broken down into usable compounds by fermentation, mostly with bacteria transmitted from mother to young.

See Ruminants Under MAMMALS: HAIR, HIBERNATION AND RUMINANTS factsanddetails.com

Yaks and Life in Tibet

Chloe Xin of Tibetravel.org wrote: “ Yaks plays a significant role in Tibetan people’s daily life. Tibetan people rely on yak milk for cheese, as well as for butter for the ubiquitous butter tea and offerings to butter lamps in monasteries. Yak meat is high in protein with only one-sixth the fat of regular beef. In the summer months it is dried, but in winter it is often eaten raw. Yak leather is used as their coats and tents. The outer hair of the yak is woven into tent fabric and rope, and the soft inner wool is spun into chara (a type of felt) and religious practices.Yak hide is used for the soles of boots and the yak’s heart is used in Tibetan medicine. Yak dung is required as a fundamental fuel, left to dry in little cakes of the walls of most Tibetan houses. In fact, so important are yaks to Tibetans that the animals are individually named just like children. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Because of their mild, kind, patient and tough characters, yaks are indispensable in the daily lives of nomadic people. The harsh weather conditions including the searing summers and the frozen winters, the dried dung of yaks is an important fuel, used all over Tibet, and is often the only fuel available on the high treeless Tibetan plateau. Yaks transport goods across mountain passes for local farmers and traders as well as for climbing and trekking expeditions. "Only one thing makes it hard to use yaks for long journeys in barren regions. They will not eat grain, which could be carried on the journey. They will starve unless they can be brought to a place where there is grass."

Yaks are sturdy, sure-footed and perfect for using as pack animals to cross high mountain passes. They can easily carry loads of 70kg (154lb) along rough and steep mountain trails. For centuries yaks have been used to carry salt from the Changtang (northern Plateau) to towns across Tibet and even across the Himalaya into the Dolpo region of Nepal. Nowadays, yaks are still used as a mode of transportation in nomadic areas and some villages. Yaks can begin being used as pack animals at age two and can often live to be over 20 years old.

When you are travelling in Tibet, you can see Mani stones everywhere. Sometimes, there are yak heads carved with Tibetan paternoster on the Mani stones. For nomadic Tibetans, yaks are so valuable that they call these animals "Norbu," meaning treasures. Yaks also find their way into artwork, such as monastery murals and rock carvings. On the street of Lhasa, you can find many vendors selling yak heads carved with Tibetan paternoster as artware. Some people use yak heads to decorate their house. In fact, when travelling in Tibet, you can find weathered or new-placed yak heads on the top of a hill, or on the bank of a river, or under an altar, even around monasteries, at the top of the gate of a village and so on. According to classics of the Bon religion, yaks came from heaven to the top of Gangdese Mountain. Of the Buddhist warriors, one had a yak's head. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

1001 Uses for a Yak

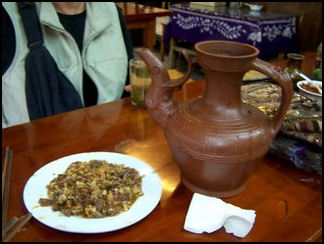

Yak meat

Yaks are arguably the most important animals in Tibet and the Himilayas. They carry goods, possessions and household goods; they provide food and hair that can be made into tents, clothes and other products. Some nomads ride on their yaks and some farmers use yaks to plow their plots of land. Yak dung is used to make fires in a land where there are no trees (many Tibetan houses have piles of drying yak dung next to the walls).

According to Animal Diversity Web: With wide hooves and the ability to carry large weights at high elevations, domesticated yak serve as beasts of burden for many inhabitants of the Tibetan plateau. The finer fur of the young is used for clothing, while the longer fur of the adult is used in making blankets, tents, etc. Also, in some areas where firewood is particularly sparse, the dung is used as fuel. In some areas, milk from the cow is used to produce large amounts of butter and cheese for export.” [Source: Matthew Oliphant, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The undercoat and hump hair is used for making cloth. The skin with hair on it is made into capes, coats and hats. The thick hide provides thick leather for boots and the soles of shoes. Yak meat is eaten. Yak milk is made into butter — which is put in tea and used to light lamps — and cheese and other dairy products (See Below). In Lhasa yak skin is even used for boats. ♠

The rough belly hair is woven into tents and blankets and spun into ropes and made into tent covering. Explaining why he prefers his yak wool tent to a house, one nomad told National Geographic, "In a tent you can hear the yaks at night if they are in trouble. And in the day you can see all around. A house is too dark." Braided black-and-white yak hair rope is highly valued.

Yak hair and fur are sold by herders for a steady income. The soft undercoat is used to make "yak cashmere" sweaters or spun into “chara” (a kind of felt) that is used to make bags, blankets, The yak heart is used in Tibetan medicine. The bones can made into glue. The Chinese cut off the white tips of yak tails and use them as ornamental tassels. In India the tails are used as flyswatters. In Japan, yak hair is used to make the wigs of Bunkaru puppets. In the 1950s in the United States, yak hair was widely used for Santa Claus beards. There is such a thing as yak cashmere.

A yak race is conducted in Qinghai once a year. The race is slow because the yaks don’t run and stop and eat grass along the away

Yaks as Food

Cooked yak meat

Unlike goats and sheep, yaks produce milk all year round. On average a yak produces eight times more milk than a goat, and 16 times more than a sheep. The milk is rich and contains double the protein and minerals of cow’s milk but it spoils in two hours, which explains why it is usually made into butter. Yak milking takes some skill.

Yak curd is both consumed fresh and dried. Some European and Nepalese cheesemakers are teaching Tibetans how to make cheese, which sells for around $14 a kilogram in Beijing and Shanghai. One European food critic who tried the cheese in Beijing said it was “young, piquant, a little dry — comparable to a cheeky Griyere...great with a glass of wine.”

Yak meat is also good but can be very tough and chewy. It is eaten cooked or dried. Although Tibetan Buddhists frown on the killing of yaks and other animals, there is no ban on the eating of yak meat.

Yaks in Mustang are not killed. But once a year they are bled and the dried blood is eaten. The tails are cut off and sold in India as fly whisks. Owners of yaks in Mustang sometimes hope their animals will fall off a cliff. Only then do they get at more than 800 pounds of yak meat. The only people allowed to kill animals are the Shembas — a low status tribe similar to the untouchable in India, who are not allowed to live in the city.⌂

The yak cheese that Tibetans eat is fermented and not very palatable to Western tastes. One NGO called Ventures in Development brought in a cheesecaker from Wisconsin and experimented with producing different kinds of aged cheese with yak milk. Fresh Yage cheese and older Geza gold have been given to chefs at trendy restaurants. Westerners who have tried the Geza say it’s smelly and a bit salty but tastes good.

Yak Butter Products

Yak butter is probably the most important thing taken from a yak. It is mixed with tea and barley gruel, and sometimes used as a hairdressing, in lamps, and for greasing squeaky prayer wheels and truck axles. Tibetans make incredibly detailed yak butter sculptures and friezes of flowers, landscapes, trees, temples, human figures animals and god and goddesses.

Yak butter stays preserved for a long time in leather bags. When sealed in airtight sheepskin bags, butter will remain edible for up to a year. But it doesn’t always seem that way. The sour smell of rancid yak butter, wrote Theroux "resembles the smell of an American family's refrigerator after a long midsummer power cut. It is the reek of old milk."

A common sound in rural Tibet is the dull rhythmic noise of milk being sloshed into butter in a yak-skin bag. The process also yields buttermilk, which is sometimes boiled down to a thick film, which is then dried in the sun for several days produces “chourpi”, a cheese which Valli said is "so hard you must chew a wad of it for ten minutes before swallowing."

Butter and cheese are also made from sheep, goats and cattle. Tibetans that were transplanted to Switzerland n the 1960s first used normal butter as a substitute when they couldn't get any yak butter, but when the cost of butter became prohibitively expensive they switched to margarine.♣

Yak Racing and Dung Energy in Tibet

Yak butter tea

Yak racing is a spectator sport held at many traditional festivals in Tibet, such as the annual Shoton Festival which usually falls in August every year. Yak race can be one of the most entertaining parts of a Tibetan horse festival, in gatherings which integrate popular dances and songs with traditional physical games. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Each of the competitors, which commonly number 10 or 12, mounts his yak, and the yaks run towards the opposite end of the race course in a sprint. Yaks can run surprisingly fast over short distances. The winner is usually given several khata (a traditional Tibetan scarf) as well as a small amount of prize money. Yak racing is also known to be performed in parts of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and in the Pamirs.

Yak dung is indispensable for cooking and heating. Generally about the size of a man’s hand, yak dung paddies are laid on a mud wall for drying before they are used as fuel. About 7,000 paddies are needed by a household to get through the winter,

See Separate Article HORSE RACING AND YAK RACING IN TIBET factsanddetails.com ; See Energy and Yak Dung in Tibet Under RESOURCES, MINING AND ENERGY IN TIBET factsanddetails.com

Yaks and Herders

Yak caravans and herds of yaks are led by a lead yak. Herders communicate with the yaks by making clicking sounds with their tongues. Often you will see young children leading the yaks. Some begin doing this as young as the age of four. The yaks themselves often have names and each animal has a distinct personality. They are sometimes adorned with red ear tassels and headpieces.

When there is too much snow or ice, yaks are fed a broth of tea, flour and nettles by their owners. Uncooperative animals are force fed. Describing the force-feeding of yak, Christome de Cherisey wrote in Smithsonian, "Dawa pushes a horn filled with broth into its mouth. The animal is recalcitrant and tries to get away; the men have to hold it still and pull on its tongue in order to force it to swallow."

A nomadic family’s migrations patterns are often geared towards making their yaks happy. Yaks often sheared of hair in early summer. Each herder has the skill to set broken bones, sear cuts and lance abbesses on their yaks. Wounds are wrapped with bandages soaked in human urine to prevent infection.

Yaks can carry 70 kilograms (150 pounds), about a forth of what a Bactrian camel can carry and about the same as a horse. Yaks are sometimes very unaccommodating pack animals and will try to throw off packs that are placed on their backs. Herders and peasants regards seeing a group of yaks as an auspicious sign but seeing a single yak of a certain color is regarded as bad luck.

Yaks are usually fairly docile but not always. Describing a yak attack, Eric Valli wrote, "One day while trekking with a caravan, a yak suddenly turns on Karma. The charge is so fast, so sudden, that Karma does not have time to move nor I to shout. The yak raises its massive head under my friend's chest, lifts him from the ground, then drops him in a heap...Surely he must have been mortally gored by the sharp, curved horns. But when we strip him we find no bleeding wounds, only a huge bruise over two broken ribs. He is unconscious and appears to be in shock."

When ever you come across a yak on the trail it is a good idea to pass on the inside, mountain side. If you pass on the outside you may find that only thing yourself navigating between a pair of long horns and the edge of a cliff.

Yak Management

According to the FAO: Management systems for yak predominantly follow a traditional pattern dictated by the climate and seasons, by the topography of the land and by social and cultural influences. Methods of keeping the yak vary from the primitive, where herds are allowed to roam virtually at will, to the technologically advanced. In general, a transhumance form of management predominates. During the warm season of summer and autumn, yak are on pastures at high elevations and the herdsmen live in campsites, which they move quite frequently. This gives way in winter and early spring to the grazing of winter pastures at lower elevations that are nearer to the more permanent winter abodes and villages of the herders and their families. The summer grazings are much the more extensive of the two. [Source: FAO]

According to the FAO: Management systems for yak predominantly follow a traditional pattern dictated by the climate and seasons, by the topography of the land and by social and cultural influences. Methods of keeping the yak vary from the primitive, where herds are allowed to roam virtually at will, to the technologically advanced. In general, a transhumance form of management predominates. During the warm season of summer and autumn, yak are on pastures at high elevations and the herdsmen live in campsites, which they move quite frequently. This gives way in winter and early spring to the grazing of winter pastures at lower elevations that are nearer to the more permanent winter abodes and villages of the herders and their families. The summer grazings are much the more extensive of the two. [Source: FAO]

“Until fairly recent years, the predominant practice in China was for all yak from several families in one or more than one village to be pooled for purposes of management but subdivided into four groups: lactating cows, dry cows, replacement stock and steers (pack yak). Since the implementation in China of the "Household Responsibility" system, which includes leasing parcels of land to the herders and private ownership of the animals, the herd of each family is rarely subdivided, although the adult females are likely to be managed separately from the rest of the animals. Some pooling of resources among small family groups may still occur.

“The proportions of each type of yak in the herd, the herd structure, can profoundly affect the output of milk and meat from the herd.

“Grazing traditions rely on accumulated experience including knowledge of the particular properties of different types of pasture vegetation. Over-grazing has become a recognized problem, especially on the winter pastures, because an increase in the yak population has occurred, at least in several of the provinces with yak in China. This increase is due, in part, to official encouragement of extra food production and in part to the fact that many herders, perhaps most, still equate numbers of animals with wealth and status, irrespective of the intrinsic merit of the animals or their productivity.

“To assist in the management of yak, there is a small range of fixtures, mainly at the winter quarters, in the form of pens and enclosures usually made of mud, turf or faeces. Wood, because of its scarcity, is used sparingly in the plateau areas. But in the alpine areas, wooden enclosures are found more often. Pens are usually associated with a tunnel-like passage for restraining animals during vaccinations or other treatments; a pit for dipping both yak and sheep is normally available; and a crush to restrain cows for mating is used in places where hand mating is practised.

“Herdsmen train yak to obey commands both by voice and by use of small stones that are either thrown or projected with a sling. The purpose is to allow one person to control a large herd. The herder normally stays with the herd to protect it from attack by wolves, especially at times of calving, and to prevent the herd from straying onto another's territory. At night, the animals are tethered near the campsite to protect them from predators and for purposes of milking the cows.

“During the warm season, yak are sent out to graze the summer pastures early in the morning and brought back to the campsite as late in the day as possible. In winter, the reverse happens with late out and early back. Milking, practised only during the warm season, is done once a day or, in some herds, twice. The method of calf rearing revolves around the frequency of milking of the cows. Milking three times a day is also practised for cows that do not have a calf at foot.

“Apart from the important task of controlling the grazing and protecting the herd, the other main tasks of the herders involve: calf rearing, milking, supervising mating, assisting with calving (but usually only for cows giving birth to hybrid calves from "improved" breeds of cattle that tend to be too large for unassisted delivery) and harvesting the fleece (most often a combination of combing out the fine down followed by shearing or shearing alone). Other routine tasks include dipping animals against external parasites, vaccinations, castrating males and training of pack animals.

“Yak and hybrids of yak and cattle are also used for ploughing for eight to ten hours a day during the planting season in areas where grazing land is combined with land suitable for cultivation. Such animals are given supplementary feeding of straw and grain. Animals used for ploughing may also be used later in the year for carrying loads on long journeys over often-difficult terrain. When working, such animals may walk continuously for seven to ten days before a rest of one or two days.

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see THE YAK: SECOND EDITION, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2003, fao.org

Image Sources: Tibet train com; Purdue University, Weird Meat blog, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025