CHIRU

Chiru (Pantholops hodgsonii) are medium-sized bovids (antelopes and goats) native to the Tibetan plateau. Also called Tibetan antelope, they resemble a cross between a reindeer and an impala and have long slightly-curved, upward-pointing black horns, black faces and grayish brown bodies covered with extremely soft, warm and thick fur. Less than 75,000 individuals are left in the wild, down from a million in the 1960s. Although the lifespan of Tibetan antelopes is not known with certainty, since so few have been kept in captivity, it is probably around eight to 10 years. [Source: Wikipedia, Jeffery Rebitzke, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

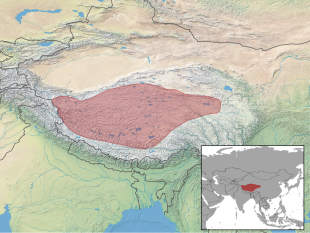

Chiru feed mainly on grass and can run very fast. They live at elevations between 3,250 and 6,000 meters (10,600 and 19,685 feet) on the arid, treeless steppes and grasslands of the Tibetan-Qinghia plateau and in the Akai Chin (a militarized zone in the Himalayas claimed by both China and India). The alpine steppes where they live have an annual precipitation of less than 40 centimeters (16 inches) . Chiru prefer open, flat or gently rolling topography, with sparse vegetation cover, but are also known to inhabit high rounded hills and mountains.

Chiru are found almost entirely in China — Tibet, southern Xinjiang and western Qinghai, between Ngoring Hu in China in the north and the Ladakh region of India in the south Today, the majority are found within the Chang Tang Nature Reserve of northern Tibet. They are especially numerous in western Qinghai province, particularly in the 77,700-square-kilometer (30,000-square mile) Kekexili area, a vast grassland where there are still large numbers of chiru and chiru breeding grounds. The chiru range once extended to western Nepal — the first specimens described, in 1826, were from Nepal — but none have been seen in Nepal for several years and the species is presumed to be extirpated from that region

Good Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article on shatoosh Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Chiru Wikipedia ; Film: “Mountain Patrol: Kekexili” is a National- Geographic-backed film about the patrols that protect the chiru in the Kekexili Reserve. It was released in China in 2004 and was popular and won the Golden Horse Award at Taiwan Film Festival. China.org article on Tibetan animals china.org.cn ;Animal Info animalinfo.org/country/china

articles under TIBETAN NATURE factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN ANIMALS AND PLANTS factsanddetails.com ; YAKS Factsanddetails.com/China ; ANIMALS AND PLANTS IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: The Chiru of High Tibet: A True Story” by Jacqueline Briggs Martin and Linda Wingerter Amazon.com; “Contesting Conservation: Shahtoosh Trade and Forest Management in Jammu and Kashmir, India” by Saloni Gupta Amazon.com; “Tibet's Hidden Wilderness: Wildlife and Nomads of the Chang Tang Reserve by George B. Schaller Amazon.com “Chang Tang A High and Holy Realm in the World” by Liu Wulin Amazon.com “Big Open: On Foot Across Tibert's Chang Tang” by Rick Ridgeway , Galen Rowell, et al. Amazon.com; “Himalayan Wildlife: Habitat and Conservation” by S. S. Negi Amazon.com; “Stones of Silence” by George Schaller Amazon.com; “Wild Animals of India, Burma, Malaya and Tibet” by Richard Lydekker Amazon.com ; “Chinese Wildlife” ( Bradt Travel Wildlife Guides) by Martin Walters Amazon.com Amazon.com; “Birds of the Himalayas” (Pocket Photo Guides) by Bikram Grewal and Otto Pfister Amazon.com “Wildlife of India” by Bikram Grewal Amazon.com

Chiru Characteristics

Adult Chiru range in weight from 26 to 40 kilograms (57.3 to 88.1 pounds) and range in height from 89 to 127 centimeters (35-50 inches). Males have a shoulder height of about 83 centimeters (33 inches); females, about 74 centimeters (29 inches), Adult males develop horns up to 60 centimeters (24 inches) in length, which females do not have. The ears of chiru are short and pointed, and the tail is also relatively short, at around 13 centimeters (5.1 inches) in length. The [Source: Jeffery Rebitzke, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=\, Wikipedia]

Chiru have a whitish belly, and thick and woolly coat. The color of their fur varies from beige and grayish to pale fawn and reddish-brown, with black markings on the face and legs. The face is almost black in colour, with prominent nasal swellings that have a paler colour in males. The fur of chiru is distinctive, and consists of long guard hairs and a silky undercoat of shorter fibres. The individual guard hairs are thicker than those of other goats, with unusually thin walls, and have a unique pattern of cuticular scales, said to resemble the shape of a benzene ring.

The long, curved-back horns of makes typically measure 54 to 60 centimeters (21 to 24 inches) in length. The horns are slender, with ring-like ridges on their lower portions and smooth, pointed, tips. Although the horns are relatively uniform in length, there is some variation in their exact shape, so the distance between the tips can be quite variable, ranging from 19 to 46 centimeters (7.5 to 18 inches). Unlike caprines (mostly goats,, the horns do not grow throughout life.

Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are significantly larger than females, weighing about 39 kilograms (86 pounds), compared with 26 kilograms (57 pounds) for females, Males can also be distinguished by the presence of horns and by black stripes on the legs, both of which the females lack. In general, the colouration of males becomes more intense during the annual rut, with the coat becoming much paler, almost white, contrasting with the darker patterns on the face and legs.

Chiru Behavior

Chiru are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). They are good runners and can move as fast as 80 kilometers per hour (50 miles per hour) When resting, chiru often dig bowl-shaped depressions in sandy and silty soil approximately 114 centimeters (45 inches) in diameter and 15.5 to 31 centimeters (6 to 12 inches) deep. The function of these depressions is not entirely known, Schaller (1996) suggested they could help conceal chiru from oestrid flies. [Source: Jeffery Rebitzke, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Chiru sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. They are considered grazers and occasionally browsers, feeding on herbs, grasses, and sedges, often digging through the snow to obtain food in winter. Their natural predators include wolves, lynx, and snow leopards, Red foxes are known to prey on young calves. George Schaller hypothesized that one reason females migrate north to calving grounds may be to avoid wolves during pregnancy and birth.

Tibetan antelope are gregarious, sometimes congregating in herds hundreds strong when moving between summer and winter pastures, although they are more usually found in much smaller groups, with no more than 20 individuals. In the past there huge herds of chiru. Cecil Rawling's wrote in his book, "The Great Plateau" which documented his explorations in Central Tibet, including the 1904-1905 Gartok expedition: "Almost from my feet away to the north and east, as far as the eye could reach, were thousands upon thousands of doe antelope with their young… Everyone in camp turned out to see this beautiful sight, and tried, with varying results, to estimate the number of animals in view. This was found very difficult however, more particularly as we could see in the extreme distance a continuous stream of fresh herds steadily approaching: there could not have been less than 15,000 or 20,000 visible at one time."

Chiru Migrations

Movement patterns among chiru populations and sexes vary depending upon the season . Males and females congregate along wintering grounds during the mating season. In spring, some females remain on winter grounds, but most females (and their female offspring if they have one) migrate north to summer calving grounds, where they remain until late July or early August. The movement of males is characterized by two patterns: some remain in the wintering grounds as resident populations while others disperse along the plateau to summer ranges. As a consequence of these seasonal movement, herd sizes vary in number, from as little as five to nearly 1000 individuals. [Source: Jeffery Rebitzke, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

During the spring most chiru migrate north. Males disperse to forage on herbs and grasses during the short three-month growing season. Females make off for their summer calving grounds, where they usually give birth to a single calf, rejoining the males at the wintering grounds in late autumn.. After giving birth, the females slowly migrate to the south with their young. Nearly half of all newborns perish during the journe, many snatched by predators such as wolves and foxes.

According to the New York Times: Chiru have the fifth longest migration of any mammal: Female Tibetan antelopes travel about 700 kilometers 430 miles each year to and from their calving grounds in the Kunlun Mountains. The Time said: to enter the top five “these Great Dane-sized bovids edged out more well-known contenders, including the millions of blue wildebeests that travel about 400 miles through the Serengeti, as well as Montana’s 270-mile pronghorn migration. [Source: Cara Giaimo, New York Times, November 13, 2019]

Chiru Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Chiru are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding. The average number of offspring is one. The gestation period ranges from seven to eight months. Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 1.5 to 2.5 years. Parental care is provided by females. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. Young males stay with their mother for one year, at which time they leave and join with other males. Female young typically stay with their mother well after their first year and accompany them during migration to the calving grounds to the north. [Source: Jeffery Rebitzke, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The rutting season for chiru lasts from November to December. Males form harems of up to 12 females, although one to four is more common. Although they appear to be non-territorial males violently defend their harem against competing males, driving them off primarily by making displays or chasing them with their head down, rather than sparring directly with their horns.

Courtship and mating are both brief, without most of the behaviour typically seen in other antelope species, although males do commonly skim the thighs of females with a kick of their fore legs. When a female approaches a male, the male prances around her with his head held high. If the female does not flee, the male then mates with her . After mating, females leave the males, and there is no apparent bond between sexes.

Mothers give birth to a single calf between mid June and early July. The calves are precocial, which means they are relatively well-developed when born. They are able to stand within 15 minutes of birth and are fully grown within 15 months, year. Mortality among young is high. Up to half of Chiru young die within the first two months of birth, and and two thirds die before two years of age. Although females may remain with their mothers until they themselves give birth, males leave their mothers within 12 months, by which time their horns are beginning to grow. Males determine status by their relative horn length, with the maximum length being achieved at around three and a half years of age.

Endangered Chiru

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List chiru are listed as Endangered. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. [Source: Jeffery Rebitzke, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

In the early 20th century several million chiru may have roamed the Tibetan Plateau. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (2000), population estimates between 1950-1960 ranged from 500,000 to one million individualsIn 1990, around 200,000 remained and it was still possible to find herds with several hundred and even several, thousand, animals. A population study conducted by R. East in 1993 revealed a population size of slightly greater than 100,000. In 1998, Schaller estimated that total population numbers were less than 75,000 individuals.

The chiru population may have dropped as low as 50,000 in the late 1990s and early 2000s as entire herds were poached. According to some estimates 20,000 chiru were killed every year during that time. The populations of chiru have bounced back as result of crackdowns on poachers. By 2006 there numbers had climbed back to around 130,000. But they are increasingly having to share their habitats with livestock. By 2010 the population of chiru reportedly improved to about 150,000, double the estimate in 1999.

Possible reasons for the decline in the numbers of chiru include: 1) loss of habitat from increased human activity in the Tibetan Plateau, such as infrastructure development, pastoral settlements, rangeland conversion for livestock grazing, and natural resource extraction; 2) adverse weather in the Tibetan plateau, which can sometimes make food scarce and foraging difficult, leading to starvation events that are particularly tough on females and young; and 3) poaching. According to the 2000 Federal Register (Department of Interior 2000), approximately 20,000 males, females, and young are killed each year by poachers, mainly for shahtoosh. See Below [Source: Jeffery Rebitzke, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Chiru Conservation

In China, chiru are Class one protected under the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Wildlife law, which prohibits the killing of any chiru with the exception of written permission by the Chinese government. Under the Wildlife Protection Act of India, Chiru are listed as a Schedule I species. The 2000 Federal Register (Department of Interior 2000) documents that any trade in shahtoosh is strictly prohibited under CITES, as well as Indian and Chinese law. /=\

Chiru are listed as endangered by the IUCN and United States Fish and Wildlife Service due to commercial poaching for their underwool, competition with local domesticated herds, and the development of their rangeland for gold mining. The chiru's wool, known as shahtoosh, is warm, soft and fine. Although the wool can be obtained without killing the animal, poachers simply kill the chiru before taking the wool. See Below

To develop testing for shahtoosh, a Hong Kong chemist and a senior forensic specialist looked at the material though a microscope. Using this method, they discovered shahtoosh contains coarser guard hairs unique to the species. By doing this, the duo had found a convenient way to prove this was poached material.

In July 2006, the Chinese government inaugurated a new railway that bisects the chiru's feeding grounds on its way to Lhasa, the Tibetan capital. In an effort to avoid harm to the animal, 33 special animal migration passages have been built beneath the railway. However, the railway will bring many more people, including potential poachers, closer to the chiru's breeding grounds and habitat. So that collisions with trains are kept to a minimum some of the 33 “migration passages” have spotlights to allow uninterrupted migration at night. Videos set up at the passages show that herds often are apprehensive about using the passages but once the lead animals use it the others follow.

Shahtoosh

Shahtoosh is an incredibly soft wool made from the fleecy underwool of the neck of chiru. It is one of the most expensive materials in the world, worth its weight in gold several times over. Shatoosh means “king of wools” in Persian. Most shahtoosh is made into two-meter-long shawls that weigh only 160 grams. These "ring shawls" are so fine and light they can be passed through a wedding band and are warm enough to hatch a pigeon egg. "Next to shahtoosh, cashmere feels like burlap" one cloth merchant told National Geographic.

Shahtoosh fibers are extremely fine (1/5 that of human hair) and are considered the softest and warmest wool in the world. Shahtoosh "ring shawls" sell in the United States for up to $30,000. The most expensive ones are off white. These are made with wool taken from the belly and the throat of the animal, which accounts for only 12 to 14 percent of a chiru’s fur. Approximately 110 to 140 grams (4-5 ounces( of shahtoosh can be processed from one Chiru carcass and three to five hides are necessary to make one shawl

Shahtoosh has been prized or centuries. It was highly valued by Mogul Emperors and presented to as a wedding gift to brides in wealthy families. Napoleon gave a shatoosh shawl to Josephine, who reportedly was so enamored by it she ordered 400 more. In India, shahtoosh is regarded as a status symbol among the rich and is one of the most valuable dowry gifts a person can give. Shahtoosh didn't really become big in the United States and Europe until the 1980s, when fur became unfashionable. One rich New York socialite told Time, "Shahtooshes are so utterly tightly woven of this wonderful thin wool. We started wearing them when people were harassed about wearing fur." Demand for shatoosh tends to increases when fur falls out favor and decreases when fur is more acceptable.

Shahtoosh Processing

It takes the fur of three to five chiru to make one six-foot shawl. Dealers who sold the shawls used to tell buyers that no animals were killed to make them. Instead, they said, they were made of fibers collected by peasants that came from hair shed or rubbed against bushes after the winter. In the old days some traders claimed the fibers came from the fictitious "toosh" bird.

Until June 2000, when a ban was imposed, the state of Jammu and Kashmir, was the only place in the world where shahtoosh could legally be produced. Many shahtoosh weavers live in the Edgar district of Srinagar, Kashmir. They make the shahtoosh shawls at home or in small workshops using handlooms. It takes a weaver about one month to a year to weave a single shawl. An estimated half million weavers make shawls.

A worker who spends a year making a $27,000 shawl earns about $540. The weavers generally don’t know any other trade. They have had an especially hard time in recent years because of the fighting in Kashmir. One weaver told the Times of London, “If there were other jobs I’d give this up instantly but unemployment here is terrible.”

Kashmir style “tooshes” are dyed and embroidered. The fibers are so fine that they must be treated with starch made from rice so they won’t break. Finished shawls sell for about $500 in India and can fetch 30 times that amount in the United States and Europe. Because the trade is lucrative people in the business are willing to take all kinds of risks.

Shahtoosh and Chiru Poaching

For a long time it was said that shatoosh was made from chiru fibers being collected from bushes that chiru rubbed against. But thus is a myth. For one thing there aren't really any bushes or trees on the Tibetan plateau for animals to rub against. The truth is the fibers come from dead chiru. According to some estimates at one time 20,000 chiru were shot and skinned by poachers every year for their soft hair. Conservationist estimated that if chiru continued to be poached as they once were they would become extinct in five to ten years. The renowned biologist George Schaller told Time, “Any woman who wears shahtoosh should be deeply embarrassed. It's not a shawl. it’s a shroud."

Most poaching has occurred in the Arjin Shan, Chang Tang, and Kekexili Nature Reserves of tibet. The most efficient way to collect shahtoosh is to kill chiru. There have been no documented cases of capture-and-release of chiru. After the chiru are killed, poachers usually skin the animal immediately and later sell the hides to dealers who arrange for the hides or shahtoosh fur to be smuggled out of China by truck or animal caravan through Nepal or India to the Indian states of Jammu and Kashmir, the only two places in the world where the possession and processing of shahtoosh is legal.

Most of the poachers in the 1990s and 2000s were Huis (Muslim Han Chinese). Many of them were former illegal miners who came to Qinghai during the gold rush in the 1980s and 90s and realized that it was much easier to make good money killing chiru than digging gold for $1 a day. The poachers used machine guns and semi-automatic weapons to hunt chiru year round, not just when their coats are the thickest. They hunted mostly at night in vehicles with bright headlights that caused the chiru to freeze in their tracks, making them easy targets to hit with a volley of bullets. Sometimes 80 or more were mowed down in a single night.

The poachers liked to attack females during the breeding season when they were pregnant, relatively slow and gathered in large numbers. A Chinese environmental group released gruesome photographs of heaps of skinned carcasses left behind by poachers. The poachers sold the pelts for between $60 and $85 a piece to middlemen who sold them for considerably higher prices to other middlemen who smuggled the airy fibers from China to India. In New Delhi, the fibers were sold to dealers in third-class hotel rooms, then sent to weavers in Kashmir. Once shahtoosh reaches Jammu and Kashmir, it is processed into expensive and fashionable shawls and scarves, then smuggled into European and United States markets.

Efforts to Stop Chiru Poaching

In China, chiru poachers face a $130 fine and a six year prison sentence if they get caught. Even so they don't seem worried. They hunt in remote areas where there is little danger of being caught. If they are caught they make enough money so they can pay off authorities with bribes.

To protect the chiru, the government has only 15 officers covering an area the size of Switzerland. There is a government unit, called "Operation No. 1, whose job it is to track down chiru poachers. But they do little. They have never caught any poachers and on one patrol they ran out of gas in the middle of nowhere and had to be rescued. The Chinese government is reportedly looking into ways to capture and domesticate chiru and harvest their wool. Conservationists are trying to come with alternative trades for weavers of shahtoosh shawls.

Trade in shahtoosh has been banned in much of Indian since 1977 but is still practiced in Kashmir, where the shawls are made. In 1995, an international ban on trade of shatoosh was signed by 142 countries. Kashmir does not abide by the treaty. Even so the market has been seriously damaged. Since the ban was imposed, sales have fallen by 50 percent. Weaving workshops that used to make 40 shawls a year now make only a dozen. Kashmiris involved in the shahtoosh trade have been arrested outside of Kashmir. In 1999, Kashmiris trading shahtoosh shawls were arrested in a number of Indian cities. Shahtoosh traders have also been arrested in Hong Kong.

A global ban on shahtoosh sales was introduced in 2002. The ban is enforced half-heartedly in Kashmir. Police ignore the problem and raids are rare. In the United States shahtoosh is sold only on the black market. The high fashion market has been targeted. Socialites have been subpoenaed for information on their shawls

The global ban has made shahtoosh more desirable in some circles. Shahtoosh is still in high demand in Europe and smuggling operations meet the demand. In Britain shahtoosh shawls are sold by wealthy women who operate like drug dealers. In Delhi they are sold under the counter at shops that sell pashmina wool products.

Wild Yak Brigade

The Wild Yak Brigade (Yemaoniu) was group of volunteers who saved chiru by tracking down poachers that kill them. Founded in 1992, the group roamed around western Qinghai looking for poachers. When the found them they tried to arrest them even though the Wild Yaks were not police and had no legal authority beyond that of ordinary Chinese citizens. They wore uniforms so they looked more official in the eyes of criminals. The 2004 film "Kekexili: Mountain Patrol" is about Kekexili's volunteer Mountain Patrol.

The Wid Yaks were made up of ex-soldiers, ex-policeman, high school graduates, herdsmen who never went to school and several former poachers. They were very poor. They often went long periods with little or no food. They relied on donations. They received two jeeps from a Chinese group called the Friends of Nature and a $10,000 grant from the U.S.-based International Fund for Animal Welfare. When they first started out they sold pelts they confiscated to make money but ended the controversial practice soon after that.

The Wild Yaks patrolled the 30,000-square mile Kekexili area in western Qinghai around 20 times a year, focusing much of their attention on chiru breeding grounds in the area and tracking poachers as if they were animals. A member of the group told U.S. News and World Report, "We follow the poachers in the dark and then in the morning, surprising them all at once, shooting above their heads because we are not allowed to shoot at them until they open fire on us. Sometimes it’s fun, but sometimes it's frightening.” In one raid the Wild Yaks captured 20 poachers and seven trucks loaded with 800 dead chiru.

The first two leaders of the Wild Yak Brigade — Suonandaijie and Zhabadoujie — were both murdered. Suonandaijie was shot dead while reloading his gun by poachers who had been captured by the Wild Yaks and then turned on them. Zhabadoujie reportedly committed suicide. Many environmentalists are skeptical about this explanation. For one, he was found with three bullets in body. How many suicide victims shoot themselves three times? In January 2001, the Wild Yak Brigade was forced to disband by the Chinese government. Leaders were relocated and the remaining members were absorbed by a rival group

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025