MAMMALS

feliformia suborder of mammals

Mammals are warm blooded animals that generate their own heat and generally have hair or fur covering all their bodies but their eyes. All but a few Australian mammals give birth to live young. The word mammal is derived from "mamma", Latin for "breast,” a reference to the fact that mammal young feed from the breasts of their mothers. Virtually all mammals play. Many mammals enjoy grooming one another.

There are between 5,000 and 5,500 species of mammals (there is a lot of debate over whether some groups are species or subspecies). Mammals are a diverse group that live in a variety of environments, from land to freshwater and oceans. About a quarter of all mammals are bats. About a half are rodents. According to the official Red List by the World Conservation Union one in four mammals species is threatened. Threats include loss of habitat and competition from alien species.

Although mammals share certain features in common, they come in a vast diversity of forms. The smallest mammals are shrews and bats that can weigh as little as three grams. The largest are blue whales, which can weigh 160 metric tons (160,000 kilograms). This means there is a 53 million-fold difference in mass between the largest and smallest mammals! There is also a great range in lifespan. Smaller mammals typically live short lives while larger mammals live longer lives. Bats (Chiroptera) are an exception to this pattern. They are relatively small mammals that can live for one or more decades. Mammalian lifespans range from one year or less to 70 or more years in the wild. Bowhead whales may live more than 200 years. Mammals have also evolved to exploit a large variety of environments and ecological niches and have a wide variety of survival strategies and lifestyles. They have developed the ability to fly, glide, swim, run, burrow, and jump and have applied these skills to a variety of functions. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

In the Class Mammalia, species are placed in 26 orders. Scientists still debate how some orders and families are related to others. The main mammal classifications are: Rodentia (rodents, 40.5 percent of all mammals), Chiroptera (bats, 22.2 percent), Eulipotyphla (moles, shrews, hedgehogs, 8.8 percent), Primates (monkeys, apes, 7.8 percent), Artiodactyla (deer, antelope, goats 5.4 percent), Carnivora (carnivores including cats, seals and bears, 4.7 percent), Diprotodontia (kangaroos, koalas 2.3 percent), and Didelphimorphia (possoms, 1.9 percent).

See Separate Article: HIBERNATION: PROCESSES, DIFFERENT TYPES, ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Animals: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org , a project to create an online reference source for every species; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org ; Biodiversity Heritage Library biodiversitylibrary.org

Origin of Mammals

The first mammals were shrewlike creatures that appeared around 225 million years, and scuttled among leaf litter mean on insects and millipedes. Mammals played secondary roles in ecosystems dominated by dinosaurs and began taking over after the mass extinction event 66 million years ago.

According to the Natural History Museum: Identified using fossil dental records, the oldest known mammal —Brasilodon quadrangularis found in Brazil — was a small ‘shrew-like’ animal that measured around 20 centimeters in length and had two sets of teeth. Mammalian glands, which produce milk, have not been preserved in any fossils found to date. Therefore, scientists have had to rely on ‘hard tissues’, mineralised bone and teeth that do fossilise, for alternative clues. The dental records for Brasilodon quadrangularis date to 225 million years ago (Late Triassic), 25 million years after the Permian-Triassic mass extinction event that led to the extinction of roughly 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrate families. Morganucodon is usually considered the first mammal but its oldest fossils, only represented by isolated teeth, date from around 205 million years ago. [Source: Natural History Museum, September 6, 2022]

Ashley Braun wrote in Natural History magazine: For millions of years, dinosaurs likely dominated the day, while prehistoric mammals kept to the protective shadows of the night. According to the longstanding “nocturnal bottleneck” hypothesis, mammals only expanded into daytime living after nonavian dinosaurs disappeared, roughly 66 million years ago. Support for this hypothesis is hard to come by, as reading clues from fossils, such as the orientation of eyes in a skull, can be unreliable. Recently, researchers have used the behavior of modern living mammals and our knowledge of their evolutionary tree to infer changes in the behavior of long-extinct mammals. [Source: Ashley Braun, Natural History magazine, February 2018; from research published in Nature Ecology and Evolution]

Ecologist Roi Maor and collaborators at Tel Aviv University, Israel, and University College London, UK gathered data from over 2,400 animal species, representing all living orders of mammals and nearly 45 percent of all known mammal species. Each species’ behavior was classified as being diurnal (mostly active during the day), nocturnal (mostly active at night), or cathemeral (active both in the day and at night). The team next mapped those behaviors onto two possible versions of the mammalian family tree that traces the evolutionary history of mammals. Finally, they used a computer model to extrapolate back in time the likely behaviors of the prehistoric mammals that evolved into modern-day mammals.

This approach allowed the researchers to estimate the rates by which mammals switched their schedules, such as when a cathemeral or nocturnal species became diurnal. Under both versions of mammalian evolutionary history, the model showed that ancient mammals started out nocturnal and that strictly daytime-dwelling mammals did not appear until after the nonavian dinosaurs died out. “We were very surprised to find such close correlation between the disappearance of dinosaurs and the beginning of daytime activity in mammals,” said Maor. The team’s models support the nocturnal bottleneck hypothesis and helps explain why many living diurnal mammals possess special adaptations to seeing at night—they may not need them today, but such adaptations helped their evolutionary ancestors survive in the time of the dinosaurs.

Mammal Characteristics

Some characteristics of mammals include: 1) Hair; 2) Four-chambered heart; 3) External ears; 4) Mammary glands in females; 5) Warm-blooded; 6) Giving birth to live young (viviparous). Many mammal groups are marked by sexual dimorphism (difference between males and females). A lot about mammals can be surmised from their teeth. Sharp, fang-like canine teeth are an indication of a meat eater. Large molars in the back are used for grinding up vegetable matter such as roots, leaves and fruit. Chisel-like front teeth are used by grazers and rodents to graze on grass and bite into nuts.

According to Animal Diversity Web: All mammals share at least three characteristics not found in other animals: three middle ear bones, hair, and the production of milk by modified sweat glands called mammary glands. The three middle ear bones, the malleus, incus, and stapes (more commonly referred to as the hammer, anvil, and stirrup) function in the transmission of vibrations from the tympanic membrane (eardrum) to the inner ear. The malleus and incus are derived from bones present in the lower jaw of mammalian ancestors. Mammalian hair is present in all mammals at some point in their development. Hair has several functions, including insulation, color patterning, and aiding in the sense of touch. All female mammals produce milk from their mammary glands in order to nourish newborn offspring. Thus, female mammals invest a great deal of energy caring for each of their offspring, a situation which has important ramifications in many aspects of mammalian evolution, ecology, and behavior. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Mammals are typically characterized by their highly differentiated teeth. Teeth are replaced just once during an individual's life (a condition called diphyodonty). Other characteristics found in most mammals include: a lower jaw made up of a single bone, the dentary; four-chambered hearts; a secondary palate separating air and food passages in the mouth; a muscular diaphragm separating thoracic and abdominal cavities; a highly developed brain; endothermy and homeothermy; separate sexes with the sex of an embryo being determined by the presence of a Y or 2 X chromosomes; and internal fertilization. Often, characteristics of skulls and dentition are used to define and differentiate mammalian groups.

Rats, squirrels, and other rodents can't vomit because their brains lack the neurological circuits associated with vomiting. Some mice tails are reinforced with bony scales, just like dinosaurs. A Japanese research team led by Ryo Okabe and Takanori Takebe awarded a 2024 Ig Nobel Prize. for their discovery that mammals can breathe through their anuses. The scientists said in a paper that their discovery offers an alternative way of getting oxygen into critically ill patients if ventilator and artificial lung supplies run low, which happened during the Covid-19 pandemic. [Source Issy Ronald, CNN, September 13, 2024; Buzzfeed]

Mammal Hair

Woolly Rhino, an Ice Age mammal

One thing that makes mammals unique is their hair, which is made of the protein keratin. All mammals have hair at some point during their development, and most mammals have hair their entire lives. Adults of some species lose most or all of their hair but, even in mammals like whales and dolphins, hair is present at least during some phase of their development.

Hair and fur are necessary for mammals to store precious heat in their body that has been generated by food supplies. Hair is dense and fine. It grows and is rooted in the skin with nerve fibers that sense movements of the hair. Even mammals such as whales and hippos and naked mole rats that appear not to have any hair do have some — on their eyelids, around their ears or other body crevices. Birds need to generate and store body heat. They use feathers rather than fur to keep heat in their bodies.

One of the key proteins in mammal hair is alpha-keratin. In recent years scientists have discovered the genes responsible for alpha-keratin and also found alpha-keratin in chickens and lizards — the closest living lineages to mammals. Lizards have alpha keratin in their claws as do mammals, which presumably during the evolution harnessed alpha-keratin in their claws to make hair.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Mammalian hair serves four main functions: 1) it slows the exchange of heat with the environment (insulation). 2) Specialized hairs (whiskers or "vibrissae") have a sensory function, letting an animal know when it is in contact with an object in its environment. Vibrissae are often richly innervated and well-supplied with muscles that control their position. 3) Hair affects appearance through its color and pattern. It may serve to camouflage predators or prey, to warn predators of a defensive mechanism (for example, the conspicuous color pattern of a skunk is a warning to predators), or to communicate social information (for example, threats, such as the erect hair on the back of a wolf; sex, such as the different colors of male and female capuchin monkeys; or the presence of danger, such as the white underside of the tail of a white-tailed deer). 4) Hair provides some protection, either simply by providing an additional protective layer (against abrasion or sunburn, for example) or by taking on the form of dangerous spines that deter predators (porcupines, spiny rats, others). [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Warm-Bloodedness

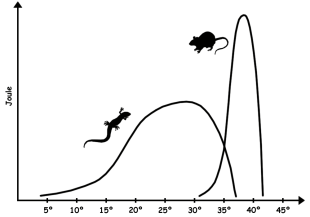

Mammals and birds are endotherms (warm-blooded animals). They require more energy intake than ectotherms (warm-blooded animals) of a similar size, and mammalian activity patterns, behavior and lifestyle often reflects their high energy demands. Mammals that live in cold climates have to stay warm, while mammals that live in hot, dry climates must keep cool and conserve water. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

"Endothermy is a defining feature of mammals, including us humans. Having a quasi-constant high body temperature regulates all our actions and behaviors, from food intake to cognition, from locomotion to the places where we live," said paleontologist Ricardo Araújo of the University of Lisbon's Institute of Plasmas and Nuclear Fusion, co-lead author of the study described below..

The high metabolisms of mammal bodies maintain internal temperature independent of their surroundings. Cold-blooded animals like lizards adopt strategies like basking in the sun to warm up. Endothermy has advantages and disadvantages. "Run faster, run longer, be more active, be active through longer periods of the circadian cycle, be active through longer periods of the year, increase foraging area. The possibilities are endless. All this at a great cost, though. More energy requires more food, more foraging, and so on. It is a fine balance between the energy you spend and the energy you intake," Araújo said. "It is maybe too far-fetched, but interesting, to think that the onset of endothermy in our ancestors may have ultimately led to the construction of the Giza pyramids or the development of the smartphone. If our ancestors would have not become independent of environmental temperatures, these human achievements would probably not be possible."

Some mammals that live in places with a cold winter hibernate. Hibernation is a process in which animals in temperate climates go a sleep and refrain from eating or drinking to survive the cold and lack of food in the winter. The metabolism of hibernating animals slows and their temperature drops by as much as 37̊F to 50̊F. The body uses just 13 percent of the energy it does when its awake.

See Separate Article: HIBERNATION: PROCESSES, DIFFERENT TYPES, ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Origin of Warm-Bloodedness

In July 2022, scientists said they had determined when warm-bloodedness first emerged by examining the ear anatomy of living and extinct mammals and their close relatives. Researchers said in a study published in the journal Nature that the reduced size of inner ear structures called semicircular canals — small, fluid-filled tubes that help in keeping balance — in fossils of mammal forerunners showed that warm-bloodedness, arose roughly 233 million years ago during the Triassic Period. Will Dunham of Reuters wrote: These first creatures that attained this milestone, called mammaliamorph synapsids, are not formally classified as mammals, as the first true mammals appeared roughly 30 million years later. But they had begun to acquire traits associated with mammals. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, July 21, 2022]

Endothermy arrived around the same time dinosaurs did. The mammalian lineage evolved from cold-blooded creatures, some boasting exotic body plans like the sail-backed Dimetrodon, mixing reptile-like traits like splayed legs and mammal-like traits like the arrangement of certain jaw muscles.

Endothermy evolved when important features of the mammal body plan were falling into place, including whiskers and fur, changes to the backbone related to gait, the presence of a diaphragm, and a more mammal-like jaw joint and hearing system.

Endothermy emerged relatively quickly, in perhaps less than a million years, rather than a longer, gradual process, said paleontologist and study co-lead author Romain David of the Natural History Museum in London. An early example was a vaguely weasel-like species, Pseudotherium argentinus, in Argentina about 231 million years ago. The later true mammals were the ancestors of today's three mammalian groups: placentals, marsupials and monotremes. "Given how central endothermy is to so many aspects of the body plan, physiology and lifestyle of modern mammals, when it evolved in our ancient ancestors has been a really important unsolved question in paleontology," said paleontologist and study co-author Ken Angielczyk of the Field Museum in Chicago.

Determining when endothermy originated through fossils has been tough. As Araújo noted: "We cannot stick thermometers in the armpit of your pet Dimetrodon, right?" The inner ear provided a solution. The viscosity, or runniness, of inner ear fluid — and all fluid — changes with temperature. This fluid in cold-blooded animals is cooler and thicker, necessitating wider canals. Warm-blooded animals have less viscous ear fluid and smaller semicircular canals. The researchers compared semicircular canals in 341 animals, 243 extant and 64 extinct. This showed endothermy arriving millions of years later than some prior estimates.

Mammal Development

There are three major groups of mammals, defined by embryonic development: 1) Monotremes (Prototheria), like platypuses, lay eggs. 2) Marsupials (Metatheria), like kangaroos, give birth to helpless and relatively undeveloped young after a very short gestation period (8 to 43 days); 3) placental mammals (Eutheria), most mammals, among whom gestation lasts much than with marsupials and young are born more fully developed. Once born, all mammals are dependent upon their mothers for milk. With marsupials, the young are born at a relatively early stage of morphological development. They attach to the mother's nipple and spend a proportionally greater amount of time nursing as they develop. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Asiatic black bear

Some mammals give birth to many relatively helpless young in each bout of reproduction. Despite being born in a relatively underdeveloped state, young of this type tend to reach maturity relatively quickly, soon producing many relatively helpless young of their own. Mortality in these species tends to be high and average lifespans are generally short. Many species that exemplify this type of life history strategy can be found among the rodents and insectivores. At the other end of the life history spectrum, many mammals give birth to one or a few precocial young in each bout of reproduction. These species tend to live in stable environments where competition for resources is a key to survival and reproductive success. The strategy for these species is to invest energy and resources in a few, highly developed offspring that will grow to be good competitors. Cetaceans, primates and artiodactyls are examples of orders that follow this general pattern.

Placenta mammal embryos grow a pad, the placenta, a complex organ that connects the embryo with the uterus. The placenta that attaches to the wall of the womb and absorbs nutrients for the embryo from the mother's blood through a tube, the umbilical cord. During gestation, eutherian young interact with their mother through a placenta. Through this system mothers can keep their young inside them until they are quite large but expelling them from their body often takes considerable effort.

In many cases, the large, dominant males that carried the banner for their species no longer exist as they have been taken by trophy hunters and poachers. Large elephants, elk, Cape buffalo and bears that were routinely killed a century ago are now rare. Scientists say they are beginning to see an evolution in reverse with elephants with small tusks and elk with less antlers having a better chance of survival than those with them. A study of big horn sheep in North America found that both males and females are getting smaller and the size of the horns has shrunk by 25 percent in the last 30 years. Scientists are also finding more tuskless elephants in both Asia and Africa.

Mammal Reproduction

Unlike reptiles and fish, who tend to produce large numbers of young and let them fend for themselves, most mammals produce smaller broods of young and expend a great amount of effort protecting and rearing them. Mammals give birth to live young partly because many mammal young need to move around to some degree to escape from predators soon after they are born.

Most mammal species are either polygynous (one male mates with multiple females) or promiscuous (both males and females have multiple mates in a given reproductive season). Because females expend so much time and energy during gestation and lactation, males can often produce many more offspring in a mating season than can females. As a consequence of this, the most common mating system for mammals is polygyny, in which relatively few males fertilize multiple females and many males fertilizing none. This situation engenders intense male-male competition in many species, and also the potential for females to be choosy when it comes to which males will sire her offspring. Related to this, many mammals have complex behaviors and morphologies associated with reproduction. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Only about three percent of mammalian species are monogamous, with males only mating with a single female each season. In these cases, males provide at least some care to their offspring. Often, mating systems may vary within species depending upon local environmental conditions. For example, when resources are low, males may mate with only a single female and provide care for the young. When resources are abundant, the mother may be able to care for young on her own and males will attempt to sire offspring with multiple females. Other mating systems such as polyandry can also be found among mammals. Some species (e.g. common marmosets and African lions) display cooperative breeding, in which groups of females, and sometimes males, share the care of young from one or more females.

All female mammals experience some type of estrus cycle in which eggs develop and become ready for potential fertilization. Hormones regulate changes in various aspects of female physiology throughout the cycle, such as the thickening of the uterine lining, and prepare the female for possible fertilization and gestation.

Many mammals are seasonal breeders, who respond to environmental stimuli such as day length, resource intake and temperature when deciding when to mate. . Females of some species store sperm until conditions are favorable, after which their eggs are fertilized. In other mammals, eggs may be fertilized shortly after copulation, but implantation of the embryo into the uterine lining may be delayed (“delayed implantation”). A third form of delayed gestation is "delayed development", in which development of the embryo may be arrested for some time. Seasonal breeding and delays in fertilzation, implantation, or development are all reproductive strategies that help mammals coordinate the birth of offspring with favorable environmental conditions to increase the chances of offspring survival.

Care of Mammal Young

Tapirs, found in the Old World (Africa) and the New World (America)

According to Animal Diversity Web: A fundamental component of mammalian evolution, behavior, and life history is the extended care females must give to their offspring. Once fertilization occurs, females nurture their embryos in one of three ways — either by attending eggs that are laid externally (Prototheria), nursing highly relatively helpless young (often within a pouch, or "marsupium"; Metatheria), or by nourishing the developing embryos with a placenta that is attached directly to the uterine wall for a long gestation period (Eutheria). Gestation in eutherians is metabolically expensive. The costs incurred during gestation depend upon the number of offspring in a litter and the degree of development each embryo undergoes. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Once the young are born (or hatch, in the case of monotremes) females feed their newborn young with milk, a substance rich in fats and protein. Because females must produce this high-energy substance, lactation is far more energetically expensive than gestation. Once mammals are born they must maintain their own body temperatures, no longer being able to depend on their mother for thermoregulation, as was the case during pregnancy. Lactating females must provide enough milk for their offspring to maintain their body temperatures as well as to grow and develop. In addition to feeding their young, females must protect them from predators. In some species, young remain with their mothers even beyond lactation for an extended period of behavioral development and learning.

Depending upon the species and environmental conditions, male mammals may either provide no care, or may invest some or a great deal of care to their offspring. Care by males often involves defending a territory, resources, or the offspring themselves. Males may also provision females and young with food.

Mammalian young are often born in an relatively helpless state, needing extensive care and protection for a period after birth. Most mammals make use of a den or nest for the protection of their young. Some mammals, however, are born well-developed and are able to locomote on their own soon after birth. Most notable in this regard are artiodactyls such as wildebeest or giraffes. Cetacean young must also swim on their own shortly after birth.

Mother’s Milk Altered Based on Baby’s Gender

In 2014, Associated Press reported: A special blend of mother’s milk just for girls? New research shows animal moms are customizing their milk in surprising ways depending on whether they have a boy or a girl. The studies raise questions for human babies, too — about how to choose the donor milk that’s used for hospitalized preemies, or whether we should explore gender-specific infant formula. “There’s been this myth that mother’s milk is pretty standard,” said Harvard University evolutionary biologist Katie Hinde, whose research suggests that’s far from true — in monkeys and cows, at least.Instead, “The biological recipes for sons and daughters may be different,” she told a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. [Source: Associated Press, February 16, 2014]

“Pediatricians long have stressed that breast milk is best as baby’s first food. Breast-fed infants are healthier, suffering fewer illnesses such as diarrhea, earaches or pneumonia during the first year of life and less likely to develop asthma or obesity later on. But beyond general nutrition, there have been few studies of the content of human breast milk and how it might vary from one birth to the next or even over the course of one baby’s growth. That research is difficult to conduct in people.

“So Hinde studies the milk that rhesus monkey mothers make for their babies. The milk is richer in fat when monkeys have male babies, especially when it’s mom’s first birth, she found. But they made a lot more milk when they had daughters, Hinde discovered. Milk produced for monkey daughters contains more calcium, she found. One explanation: Female monkeys’ skeletons mature faster than males’ do, suggesting they need a bigger infusion of this bone-strengthening mineral.

Mothers’ milk even affects babies’ behavior, she said. Higher levels of the natural stress hormone cortisol in milk can make infants more nervous and less confident. But boys and girls appear sensitive to the hormone’s effects at different ages, her latest monkey research suggests.

Mammal Senses and Communication

Olfaction (smelling) plays an important role in many of mammal activities, including foraging, mating and social communication. According to Animal Diversity Web: Many mammals use pheromones and other olfactory cues to communicate information about their reproductive status, territory, or individual or group identity. Scent-marking is commonly used to communicate among mammals. They are often transmitted through urine, feces, or the secretions of specific glands. Some mammals such as skunks even use odors as defense against mammalian predators, which are especially sensitive to foul-smelling chemical defenses. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Typically, mammalian hearing is well-developed. In some species, it is the primary form of perception. Echolocation, the ability to perceive objects in the external environment by listening to echoes from sounds generated by an animal, has evolved in several groups. Echolocation is the main perception channel used in foraging and navigation in microchiropteran bats (Chiroptera) and many toothed whales and dolphins (Odontoceti), and has also evolved to a lesser degree in other species such as shrews.

Vision is well-developed in a large number of mammals, although it is less important in many species that live underground or use echolocation. Many nocturnal animals have relatively large, well-developed eyes. Vision can be important in foraging, navigation, entraining biological rhythms to day length or season, communication, and nearly all aspects of mammalian behavior and ecology.

Many mammals are vocal, and communicate with one another using sound. Vocalizations are used in communication between mother and offspring, between potential mates, and in a variety of other social contexts. Vocalizations can communicate individual or group identity, alarm at the presence of a predator, aggression in dominance interactions, territorial defense, and reproductive state. Communication using vocalizations is quite complex in some groups, most notably in humans.

Mammals also perceive their environment through tactile input to the hair and skin. Specialized hairs (whiskers or "vibrissae") have a sensory function, letting an animal know when it is in contact with an object in its external environment. Vibrissae are often richly innervated and well-supplied with muscles that control their position. The skin is also an important sensory organ. Often, certain portions of the skin are especially sensitive to tactile stimuli, aiding in specific functions like foraging (e.g., the fingers of primates and the nasal tentacles of star-nosed moles). Touch also serves many communication functions, and is often associated with social behavior (e.g., social grooming).

Carnivores and Mammal Feeding

chevrotain (mouse deer), a ruminant like sheep, horses, cows and water buffalo

Mammals eat a huge variety of different things. They are generally divided among: 1) animal-eating carnivores (most species within Carnivora), 2) plant-eating herbivores (Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla), or omnivores (eat plants and animals, which includes many primates). Mammals eat both invertebrates and vertebrates (including other mammals), plants (including fruit, nectar, foliage, wood, roots and seeds) and fungi. Being warm-blooded, mammals require much more food than cold-blooded animals of similar sizes. Because of this, relatively few mammals can have a large impact on ecosystems and populations of their food sources. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

No animal can create its own food like a plant does. All animals must get their food from outside their bodies, with the ultimate source being plants. Animals that eat plants directly are called herbivores. Those that eat other animals are called carnivores. Even carnivores are ultimately dependent on plants because the animals they eat either eat plants or animals that eat plants or animals that eat animals that eat plants.

Carnivores are among the most advanced animals. Meat is muscle and is one of the richest, most-energy-packed of all foods. Many carnivores have large brains, in part because catching prey takes more skill and brain power than eating a plant.

Carnivores generally have teeth such as canines that are used to stab the victim and perhaps kill it near the front of their mouth and other teeth (carnassials in mammals) further back in jaws that cut and grind the meat up make it easier to swallow and digest. Unless an ecosystem has been disturbed wherever you find large numbers of herbivores you can find carnivores that feed on them. Most large animals found on the land are mammals.

Carnivorous mammals — or animals — generally fall into two groups: 1) those that feed on large prey; and 2) those that will feed on small bite size prey, often things like insects or earthworms. As a carnivore get bigger in size the more small creatures fail to meet its nutritional needs, with the tipping point being about 20 kilograms, about the size of a coyote, after which point it make more sene to pursue big game.

Ruminants

Cattle, sheep, goats, yaks, buffalo, deer, antelopes, giraffes, and their relatives are ruminants — cud-chewing mammals that have a distinctive digestive system designed to obtain nutrients from large amounts of nutrient-poor grass. Ruminants evolved about 20 million years ago in North America and migrated from there to Europe and Asia and to a lesser extent South America, where they never became widespread.

As ruminants evolved they rose up on their toes and developed long legs. Their side toes shrunk while their central toes strengthened and the nails developed into hooves, which are extremely durable and excellent shock absorbers.

Ruminants helped grasslands remain as grasslands and thus kept themselves adequately suppled with food. Grasses can withstand the heavy trampling of ruminants while young tree seedlings can not. The changing rain conditions of many grasslands has meant that the grass sprouts seasonally in different places and animals often make long journeys to find pastures. The ruminants hooves and large size allows them to make the journeys.

Describing a descendant of the first ruminates, David Attenborough wrote: deer move through the forest browsing in an unhurried confident way. In contrast the chevrotain feed quickly, collecting fallen fruit and leaves from low bushes and digest them immediately. They then retire to a secluded hiding place and then use a technique that, it seems, they were the first to pioneer. They ruminate. Clumps of their hastly gathered meals are retrieved from a front compartment in their stomach where they had been stored and brought back up the throat to be given a second more intensive chewing with the back teeth. With that done, the chevrotain swallows the lump again. This time it continues through the first chamber of the stomach and into a second where it is fermented into a broth. It is a technique that today is used by many species of grazing mammals.

Ruminant Stomachs

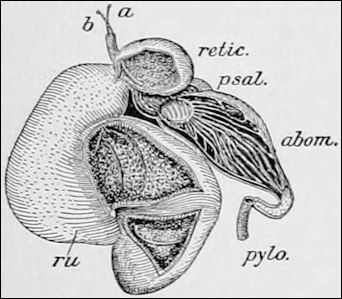

Ruminant stomach Ruminants chew a cud and have unique stomachs with four sections. They do no digest food as we do, with enzymes in the stomach breaking down the food into proteins, carbohydrates and fats that are absorbed in the intestines. Instead plant compounds are broken down into usable compounds by fermentation, mostly with bacteria transmitted from mother to young.

The cub-chewing process begins when an animal half chews its food (mostly grass) just enough to swallow it. The food goes into the first stomach called the rumen, where the food is softened with special liquids and the cellulose in the plant material is broken down by bacteria and protozoa.

After several hours, the half-digested plant material is separated into lumps by a muscular pouch alongside the rumen. Each lump, or cud, is regurgitated, one at a time and animal chews the cud thoroughly and then swallow it again. This is referred to a chewing the cud.

When the food is swallowed for the second time it by passes through the first two chambers and arrives at the third chamber, the "true" stomach, where it is digested. As the chewed food moves through this chamber microbes multiply and produce fatty acids that provide energy and use nitrogen in the food to synthesize protein that eventually becomes amino acids. Vitamins, amino acids and nutrients created through chemical recombination then move in the intestine and pass through linings in the gut into the bloodstream.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Mostly National Geographic articles. Also “Life on Earth” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press), New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2024