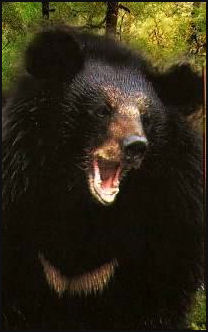

BEAR CHARACTERISTICS

As a group bears look a lot alike. They vary in size and color but have the same general shape. The shapes and features of members of the cat family, for example, are much more varied.Bears are large, robustly built animals with very short tails. . The smallest species, sun bears, range in size from 25 to 65 kilograms (55 to 143 pounds); the largest, polar bears, can weigh up to 800 kilograms (1764 pounds). bears). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females, sometimes more than twice their size. [Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bears are stockily built and have relatively short legs, necks and tails and strong curved claws. Most bears have a thick hid and thick hair, which keeps them warm in cold weather and protects them from insects in warm and hot weather. Most species have long, rough fur, and the hairs that make it up are generally unicolored (rather than being agouti, the common pattern among mammals). Sun bears have a smooth coat. Most bears are brown, black, or white; some have striking white marks on the chest or face. Giant pandas are well-known for their distinctive bands of black and white fur.|=|

Bears have small, rounded ears and small eyes and unusually small eyes for such large animals. Bear skulls are wlongayed and massive, with unspecialized incisors, elongate canines, reduced premolars, and bunodont cheek teeth. Their teeth are large and pointed but not particularly useful for eating meat as they have lost their shearing ability. In contrast their molars are heavy and thick, ideal for crushing plant material. Bear teeth grown continually through the animal’s life and tiny growth rings are created every year, allowing scientists to use them to determine a bear’s age. Bear cheekteeth are bunodont,(low, rounded cusps that are separate and hill-like) and the carnassials are flattened and specialized for crushing, not secodont. The incisors are unspecialized; the canines are long and slightly hooked; and the first three premolars are small and weakly developed if present at all. The dental formula is 3/3, 1/1, 3-4/4, 2/3 = 40-42. [Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Grizzly bears have an average life span of around 25 years. A grizzly bear in captivity has lived to the age of 40. The average longevity of black bears is 12 years. A black bear has lived to the age of 38. Studies of grizzlies at Yellowstone National park indicate that male cubs outnumber female cubs two to one. At the age of three and four males and females are equally numerous. Among adults female predominate.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BEARS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, HABITAT, HUMANS, PIZZLIES factsanddetails.com

BEAR HIBERNATION, REPRODUCTION, CUBS factsanddetails.com

BEAR BEHAVIOR: TERRITORIALITY, HABITUATED TO HUMANS, OPENING CARS factsanddetails.com

BROWN BEARS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, SIZE factsanddetails.com

BROWN BEAR FEEDING: DIET, HABITS, HUNTING, SALMON factsanddetails.com

BROWN BEAR BEHAVIOR: SENSES, HIBERNATION, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

POLAR BEARS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BEAR SPECIES IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

SUN BEARS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ASIATIC BLACK BEARS (MOON BEARS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

SLOTH BEARS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

SLOTH BEARS AND HUMANS: DANCING, QALANDERS AND ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

BEARS: BILE, BODY PARTS, CHINESE MEDICINE AND FOOD DELICACIES factsanddetails.com

Bear Body and Movement

All bear species have robust, recurved, non-retractile claws that they use for digging and ripping. The feet of bears are plantigrade (used for walking on the soles of the feet, like a human), and most have hairy soles, although tree climbing bears, such as sun bears, have naked soles. There are five digits on each foot. Giant pandas have an additional, opposable feature of the forepaws, sometimes called a panda's "thumb". It is not a true digit but a pad-covered enlargement of the radial sesamoid bone. Pandas use this opposable structure to manipulate bamboo. [Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bears tend to move relatively slowly, with a shuffling, plantigrade gait, but are capable of running quickly when necessary, standing and walking on the rear two feet, and climbing. Polar bears are excellent swimmers and other bears can also swim. Sun bears are quite arboreal. Most bears move throughout a large range in order to meet their metabolic needs. Polar bear females migrate off of pack ice in late fall to give birth to their young in dens. |=|

Bears tend to move relatively slowly, with a shuffling, plantigrade gait, but are capable of running quickly when necessary, standing and walking on the rear two feet, and climbing. Polar bears are excellent swimmers and other bears can also swim. Sun bears are quite arboreal. Most bears move throughout a large range in order to meet their metabolic needs. Polar bear females migrate off of pack ice in late fall to give birth to their young in dens. |=|

Bears walk on the heels of their feet like humans and move both legs on each side of their body at the same time when they walk which gives them and ambling, rolling gait. They can also move quite fast for such bulky-looking animals. If necessary brown bears can run short distances between 35mph and 40mph.

Bears can stand on their hind legs and strike out with their front claws. When they stand its often to look around and sniff the air. Their claws are nonretractable. Even so bears are quite adept at manipulating objects with their front feet. Most bears are good tree climbers and decent swimmers but are unable even to make even a small jump.

Many bears are good tree climbers. Black bears have curved claws and climb trees to escape danger or find food (brown bears generally are too big to climb trees). They climb by hugging the tree with their forelegs and pulling themselves up. They go down in a similar fashion feet first (unlike cats that often descend head first).

Bear Senses and Navigation

Bears sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Bears have a fairly good sense of hearing and an extremely keen sense of smell, by some estimates, seven times stronger than a bloodhound. It said that polar bears can smell the presence of a seal or a sandwich from more than a kilometer away. Bears use their sensitive lips to locate and maneuver food.

Contrary to the popular myth, they have good eyesight. They are especially adept at detecting movement at long distances. They appear to have some color vision but are very short sighted. Evidence of good eyesight include the fact they are active during both day and night and zoo bears are good at catching food tossed to them from some distance away and also adept at distinguishing between food and non-food items such as rocks. North American black bears have color vision and have been shown to use vision to distinguish food items at close range

Bears can navigate over long distances. Brown bears that have been moved more than a hundred miles form their home territory are have been able to find their way back. There is some evidence that bears find their way back toby using the earth's magnetic fields. In a Michigan a black bear found its way home after being airlifted to a new location 251 kilometers away. In Alaska, a brown bear had to swim at least 15 kilometers from an island it was relocated to to reach its mainland home territory.

Bear Eating Habits and Predation

Bears are omnivorous (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals) and opportunistic. They can also recognized as carnivores (eat meat or animal parts), herbivores (eat plants or plants parts), folivores (eat leaves). Bears spend much of their time feeding. They are mainly vegetarians and they eat a wide variety of things. They often live on a feast and starve diet, eating lots when is plentiful and nothing when it scarce. The chief limiting factor for bear populations is food supply.

Bears locate food by smell, sniffing with their long mobile snout. They seem to prefer some foods when they have maximum protein content — usually during preflowering or early flowering stages. According to the book Bears of the World: “A bear normally spends its time in a series of small areas where it can find food. Collectively, these areas make up its home range. It moves around within the range in order to take advantage of seasonal food sources. The routes to and from these areas are often called travel lanes.

Once bears reach their adult size it is unlikely that they will be subject to predation. Cubs are at risk of predation from member of their own species bears, sympatric bear species, and other large predators, such as large cats and canids. Female bears are aggressive in defense of their young.

Bear Diet

Bears feed on berries, roots, bulbs, nuts, tubers, grasses, sedges (protein-rich plants), and leaves. But they can also be skilled hunters and opportunistic feeders who feed on fish, birds, mice, gophers, deer, and rodents and even insects (an important source of protein when meat is scarce). Some bears love cowberries. Other are fond of ants and honey. Animal protein sources include insects, fish and small mammals. Many bears scavenge dead animals. Bears in coastal areas often feed on walrus, seal and whale carcasses that wash ashore. Some black bears have been observed eating moose and deer scat.

According to Animal Diversity Web:: Specific food types may vary by habitat or season. For example, North American brown bears (Ursus arctos) may rely extensively on fruits and insect larvae throughout the year, or may prey extensively on calves during ungulate breeding seasons and on migrating fish. Most species eat primarily fruits and insect larvae but will include vertebrates when they can, carrion, honey, forbs and grasses, seeds, nuts, tubers, fish, and eggs. Bears use their formidable strength, massive forelimbs, and robust claws to tear apart logs and capture prey. Giant pandas are dietary specialists, eating primarily bamboo stems and shoots, but will also include small vertebrates, insects, and carrion in their diet. Polar bears (Polar bears) are the most carnivorous species, preying mainly on seal species, but including fish, small mammals, birds and their eggs, and will scavenge carcasses of whales, walruses, and seals. [Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

When available bears will eat from garbage dumps. Contrary to popular myth, garbage-eating bears do not become dependent on dumps as a food source. While feeding on garbage they also continue to eat normal bear food like roots and berries. The main problem with garbage bears is that they became a nuisance to humans and are sometimes shot.

Bear Eating Physiology

Eric J. Wald of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service wrote: Patterns of morphological variation in the skulls of extant bears were studied as they relate to diet and feeding behaviour. Measurements of craniodental features were used to compute indices that reflect dietary adaptations of the dentition and biomechanical properties of the skull, jaw and related musculature. Species were classified as either carnivores, omnivores, herbivores or insectivores. Results demonstrated significant morphological separation among all four groups. Carnivores were distinguished by, among other features, molar size reduction, flexible mandibles and, most surprisingly, relatively small carnassial blades. In contrast, herbivores displayed, among other features, large molar grinding areas, rigid mandibles and large carnassial blades. The insectivorous sloth bear was characterized by extreme reduction of the post-canine teeth. As expected, omnivores tended to have morphology intermediate between that of carnivorous and herbivorous ursids.

P. Christiansen wrote in the Journal of Zoology: Bite forces (BFs) based on a dry skull static model were computed for 122 specimens of all eight species of extant ursids. It was found that the giant panda has high BFs for its body size, and large moment arms about the temporomandibular joint, both muscle inlever moment arms and outlever moment arms to the carnassial and canine. The insectivorous sloth bear and to some extent the omnivorous black bears were the opposite. The small sun bear has very large canines and high BFs, which are not well understood, but could potentially be related to its frequent opening of tropical hardwood trees in pursuit of insects.

Force profiles along the lower jaw revealed significant differences among the various species, both related to diet and inferred applied BFs. The panda is the only specialized ursid with respect to craniodental morphology and BFs, but is still unspecialized for herbivory compared with other large, herbivorous mammals, probably owing to a rather short evolutionary history, but possibly its morphology is constrained by genealogy. The low BFs in the sloth bear and its mandibular force profiles are derived for a diet of insects and fruit, requiring only low BFs and largely dorsoventral bite moments. In contrast, the unspecialized morphology and moderate BFs relative to body size of the polar bear and spectacled bear are probably also a result of a short evolutionary history.

Lifespan and Health of Bears

Bears are long-lived if they survive their first few years of life. Most mortality occurs in young cubs or dispersing juveniles as a result of food stress. Pre-weaning cub mortality was estimated at 10-30 percent in polar bears and sub-adult mortality at between three and 16 percent. In American black bears in Alaska, sub-adult mortality was estimated at 52 to 86 percent. Estimates of longevity in the wild are as high as 25 years. Captive brown bears have lived to 50 years or more (Ursus arctos). [Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bears suffer from many of the same maladies that humans do including arthritis, hemorrhoids and teeth cavities. At least 55 kinds of internal and external parasites are known to infest bears. They include fleas, ticks, tapeworms, hookworms and roundworms. Infection by Trichinella spiralis (pork worms) is especially common, affecting up to 60 percent of Polar bears and brown bears. These wprms cause a parasitic nematode worm responsible for the parasitic disease trichinosis, also known as trichinellosis.

Bears are hosts of many internal (over 50 types of worms in their intestines and lungs) and external (black flies, mosquitoes, midges) parasites. Each can potentially weaken a bear, which may lead to injury or death by other causes. At Brooks, especially toward the end of summer and into fall, bears sometimes shed a type of tapeworm, commonly called the broad fish tape worm. It can sometimes be seen trailing behind them. Bears can become infected by the tapeworm from eating raw salmon. [Source: U.S. National Park Service, September 30, 2016]

Among the endo and ectoparasites, that infect bears are protozoans (Eimeria and Toxoplasma), trematodes (Nannophyetus salminicola, Neoricketsia helminthoeca), cestodes (Anacanthotaenia olseni, Mesocestoides krulli, Multiceps serialis, Taenia species, and Diphyllobothrium species), nematodes (Baylisascaris transfuga, B. multipapillata, Uncinaria yukonensis, U. rauschi, Crenosoma, Thelazia californiensis, Dirofilaria ursi, Trichinella spiralis, and Gongylonema pulchrum), lice (Trichodectes pinguis), fleas (Chaetopsylla setosa, C. tuberculaticeps, Pulex irritans, and Arctopsylla species), and ticks (Dermacentor and Ixodes species).|=|

Age Determination of Bears Using Teeth and Skulls

B. P. Zavatsky wrote: To understand many aspects of the biology of bears, it is necessary to establish age of animals. Without this ability, it is impossible to determine the age structure of the population, rate of growth, onset of sexual maturity, lifespan, etc. Accurate age of bears after one year may be determined by the number of layers in dental root cement. The first work on this technique was reported by Smirnov (1960) ... 'in the bear, the layer of cement is most exact and one can consider that each layer signifies one year of life.' Rausch (1961) studied American bears of known age and established that there is an annual layer of dentine and cement and also a yearly outgrowth on the root of the tooth; according to the number of annual layers in the length of the tooth, one can distinguish ten age classes. Mundy and Fuller (1964) determined the age of grizzlies by the cement layers of the third molar. Because the third molar of the lower jaw cuts through in the bear in the second year of life, its age can be determined by the number of cement layers plus one year. [Source:B. P. Zavatsky, Borogov State Agricultural Enterprise, Krasnoyarsk Kray, U.S.S.R., “Bears: Their Biology and Management” Vol. 3, A Selection of Papers from the Third International Conference on Bear Research and Management, Binghamton, New York, USA, and Moscow, U.S.S.R., June 1974. IUCN Publications New Series no. 40 (1976), pp. 275-279

Manning (1964) took as significant the degree of concretion of skull sutures, the thickness of enamel on teeth, and the form of the skull outgrowths as a technique in the determination of the age of the polar bear. By these criteria he identified four age classes and determined the ages of the bears to the sixth year. Sauer, Fry and Brown (1966) determined the ages of black bears (Ursus americanus) according to the lengths of the incisors to a thickness of 250 microns in sequential sections of 25 microns. They discovered that wild bears did not differ from bears living in captivity. They showed that sequential layers of cement did not always correlate with age or were sometimes completely absent, and in wild bears of known age each cement layer corresponded to one year in the life of the bear. Ushivtsev (1972) used the same criteria for determining the age of the brown bear of Sakhalin Oblast and came to the same conclusion. Inukai Masaaki (1972) discovered that the age of the brown bears of Hokkaido, according to sections of the incisors, up to a year old cannot be determined by this method because there were no definite layers of dental cement, but in older bears they are in annual layers.

Thus all researchers attempting to determine the ages of bears came to the same conclusion: that the number of layers of tooth cement corresponds to a year in the life of the bear. This position was taken for the basis of our studies and thus accurate growth of bears of the Turykhan population was determined according to the number of cement layers at the root of the tooth. As the basis of our research on the skulls of brown bears in the Borogov State Agricultural Enterprise, located in the middle Yenesey region (33, 040 sq. km.), forty-three skulls were collected between 1967 and 1973 from bears in a comparatively small region. Therefore, errors connected with geographical variability of the species can be excluded.

The analysis of the collected material was conducted according to the method of Klevezal and Kleynenberg (1967) on microtome sections of roots of bear teeth. To select the most suitable tooth from several skulls of the collection, we sliced all teeth, sections of jaws, and different parts of each tooth. You have to have access to jstor for the rest

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025