BEAR HIBERNATION

Hibernating bears hibernate from two to six months, even in warm climates where there is plentiful food supply. Some individuals of hibernating species don’t hibernate even when there is a lot of snow and food is in short supply. Hibernation seems to be triggered by low temperatures, shorter days and snow and coincides with the disappearance of high-quality food. During late summer some bears eat over 20,000 calories a day to put on enough fat to last them through the winter. During the days before hibernation some species eat highly fibrous materials that act as anus plugs during hibernation. If given sufficient food zoo bears don’t hibernate.

It was long thought that bears don't hibernate in the true sense of the word in that their temperature remains relatively normal and they can easily be roused from their sleep. The temperature of true hibernating animals — namely small mammals such as chipmunks or marmots — drops much lower, sometimes to near zero, and they can not be easily roused. Bears go into a dormant state and have a significate drop in pulse rate (8 beats a minute as opposed to 40 0r 50 beats a minute when sleeping in the summer) and breathing rate but their body temperature only drops 3 to 5°C (5 to 12°F), compared with the much larger drops — often 32 °C (60 °F) or more — as observed in other hibernators. The temperature of black bears drops from a normal of 100°F or 101°F to 88°.

The theory that the deep sleep of bears was not comparable with true, deep hibernation was refuted by research in 2011 on captive black bears and again in 2016 in a study on brown bears. In the 2016 study, wildlife veterinarian and associate professor at Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Alina L. Evans, researched 14 brown bears over three winters. Their movement, heart rate, heart rate variability, body temperature, physical activity, ambient temperature, and snow depth were measured to identify the drivers of the start and end of hibernation for bears. This study built the first chronology of both ecological and physiological events from before the start to the end of hibernation in the field. [Source: Wikipedia]

The 2016 study found that bears would enter their den when snow arrived and ambient temperature dropped to 0 °C (32 °F). However, physical activity, heart rate, and body temperature started to drop slowly even several weeks before this. Once in their dens, the bears' heart rate variability dropped dramatically, indirectly suggesting metabolic suppression is related to their hibernation. Two months before the end of hibernation, the bears' body temperature starts to rise, unrelated to heart rate variability but rather driven by the ambient temperature. The heart rate variability only increases around three weeks before arousal and the bears only leave their den once outside temperatures are at their lower critical temperature. These findings suggest that bears are thermoconforming and bear hibernation is driven by environmental cues, but arousal is driven by physiological cues.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BEARS: HISTORY, EVOLUTION, HABITAT, HUMANS, PIZZLIES factsanddetails.com

BEAR CHARACTERISTICS: PHYSIOLOGY, DIET, LIFESPAN factsanddetails.com

BEAR BEHAVIOR: TERRITORIALITY, HABITUATED TO HUMANS, OPENING CARS factsanddetails.com

BROWN BEARS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, SIZE factsanddetails.com

BROWN BEAR FEEDING: DIET, HABITS, HUNTING, SALMON factsanddetails.com

BROWN BEAR BEHAVIOR: SENSES, HIBERNATION, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BEAR SPECIES IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

SUN BEARS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ASIATIC BLACK BEARS (MOON BEARS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

SLOTH BEARS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

SLOTH BEARS AND HUMANS: DANCING, QALANDERS AND ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

BEARS: BILE, BODY PARTS, CHINESE MEDICINE AND FOOD DELICACIES factsanddetails.com

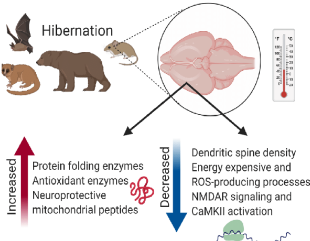

Physical Processes of Bear Hibernation

Bears consume no food or water and don’t urinate or defecate while hibernating (smaller mammals by contrast have to periodically wake up and eat and expel waster). The water content of the blood remains at a constant level. The small amount of water loss that occurs naturally is offset by the breakdown of fat reserves to secure moisture. Hibernating bears stay hydrated with the metabolic water that is produced in sufficient quantities to satisfy their water needs. Bears burn about 4,000 calories a day while hibernating, living off their stored fat. The sometimes shiver while hibernating to stay warm. After they wake up it takes several weeks for them to resume normal eating, presumably because it takes some time for the metabolism to resume to normal.

Bears are able to recycle their proteins, allowing them to avoid muscle atrophy. The bones of hibernating bear don't lose calcium and become brittle. Scientist are studying this phenomena as way of treating older people with osteoporosis. Sleeping bears don't suffer from obesity even though they sometimes carry huge amounts of fat. They tolerate high levels of cholesterol without developing arteriosclerosis; burn about 4,000 calories a day, but limit the fuel to body fat while preserving protein reserves. Scientists are studying these processes to help burn victims (who often die of rapid protein depletion).

Bears emerge from their dens after the hibernation is over with no significant loss of muscle strength. Humans immobile for the same amount of time lose 90 percent of their muscle strength. Nitrogenous waste of hibernating bears is recycled through the bladder and reabsorbed and not excreted as urine. Their body reprocesses the urine and converts it to an amino acid that is necessary to keep the bear alive. Scientist are studying how bears do this as a way of helping people whose kidneys have failed.

Bears increase the availability of certain essential amino acids in the muscle, as well as regulate the transcription of a suite of genes that limit muscle wasting. A study by G. Edgar Folk, Jill M. Hunt and Mary A. Folk compared EKG of typical hibernators to three different bear species with respect to season, activity and dormancy, and found that the reduced relaxation (QT) interval of small hibernators was the same for the three bear species. They also found the QT interval changed for both typical hibernators and the bears from summer to winter. This 1977 study was one of the first evidences used to show that bears are hibernators. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: HIBERNATION: PROCESSES, DIFFERENT TYPES, ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Dens of Hibernating Bears

Bears may hibernate in caves, hollows of trees or in a depression under some leaves but most often they hibernate in dens dug by themselves or some other animal. They often hibernate year after years in the same area, often in the same den. Sometimes they move to the dens to hibernate during snow storms so their tracks are covered up.

In the late autumn, bears become lethargic and then dig a den and hibernate. Most dens are dug well in advance of hibernating time. In the forest bears often dig their dens underneath trees, whose root system acts as a roof and line the dens with evergreen boughs. grasses and bark for warmth and perhaps comfort. Many dens are dug in slopes apparently to minimize the accumulation of water. Theee dens usually face north so they have a insulating cover of snow.

Many dens have a sleeping areas that are higher than the entrance so an igloo-like pocket of air is generated that keeps the bear warm. About one in fifteen black bears doen't bother to build a den. Sows even give birth in the open and she and her cubs sleep through the winter while the snow piles up on top of them.

Hibernating Black Bears and Applications to Humans

In a study published in February 2011 in Science of black bears in Alaska — who spend up to seven months a year hibernating without eating, drinking, urinating or defecating and emerge from their slumber no worse foe the wear — researchers found that the bears were able to drop their heart rate to just 14 beats per minute and reduce their metabolism by three quarters. In the study Øivind Tøien and colleagues from the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, placed captured bears in wooden huts designed to look like dens. The huts were fitted with infrared cameras and the researchers implanted radio transmitters into the animals to monitor their body temperature, heart rate and muscle activity. "We wanted to follow metabolism to see whether or not the animals were regulating body temperature. We wanted to study EEG in order to reveal their sleep states and circadian rhythms," said Craig Heller of Stanford University in Washington DC, who took part in the study. [Source: Alok Jha, The Guardian, February 17, 2011]

Alok Jha wrote in The Guardian, “The scientists monitored the bears during five months of hibernation and watched as their body temperatures fluctuated between 30̊C and 36̊C in cycles lasting two to seven days. These fluctuations have never been seen before in hibernating animals. "A very important clue to understand what is going on with the bears' metabolism is their body temperatures," said Tøien. "We knew that bears decreased their body temperatures to some degree during hibernation, but in Alaska we found that these black bears regulate their core temperature in variable cycles over a period of many days, which is not seen in smaller hibernators and which we are not aware has been seen in mammals at all before."

When a typical animal hibernates, its metabolism slows down by about half for every 10̊C drop in body temperature. The bears' metabolism dropped to a quarter of normal, but their body temperature only fell by 5-6 ̊C. Their heart rates also slowed from around 55 beats per minute to about 14 beats per minute. At the end of the hibernation season, it took the bears a while to get back to normality – their metabolism remained suppressed for up to three weeks after they emerged from sleep. "That indicates there's some biochemical mechanism that suppresses metabolism and that could be a very interesting discovery," said Heller.

Brian Barnes, also of the University of Alaska and another author of the study, noted that when black bears emerge from hibernation in spring, they have not suffered the losses in muscle and bone mass and function that would be expected to occur in humans over such a long period of immobility and disuse. "If we could discover the genetic and molecular basis for this protection, and for the mechanisms that underlie the reduction in metabolic demand, there is the possibility that we could derive new therapies and medicines to use on humans to prevent osteoporosis, and disuse atrophy of muscle," he said, "or even to place injured people in a type of suspended or reduced animation until they can be delivered to advanced medical care – extending the golden hour [when medical intervention is most effective] to a golden day or a golden week."

Heller also pointed to lessons that the hibernation study could have for deep-space exploration. "There has always been a thought that, if there is ever long-distance space travel, it would be good to be able to put people into a state of lower metabolism or suspended animation – that's almost science fiction but you can see the rationale."

Bear Reproduction

Bears engage in seasonal breeding and year-round breeding and all species employ delayed implantation (a condition in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the uterine lining, sometimes for several months). Gestation lengths ranging from 95 to 266 days, with implantation being delayed from 45 to 120 days. Actual gestation lengths may be closer to 60 to 70 days. Bears give birth to one to four young, usually two, at intervals of one to four years. Births in temperate species occur during the winter when the female is dormant. [Source: Tanya Dewey and Phil Myers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Bears have a slow reproductive rate. Females take four to six years to reach sexual maturity, raise one or two cubs and mate every other year because they usually spend two years of more with their cubs. At any given time only about a third of the available females breed. The others are mostly taking care of cubs. If the supply is reduced, say because of a drought, sometimes females do not reproduce.

Births in sun bears may occur at any time of the year. For other bear species the breeding season usually last from late May to mid July but the egg does not implant into the womb until the fall. Utilizing a process known as delayed implantation a fertilized egg can “free float” in the female’s uterus for up to five months before attaching to the uterus wall and beginning development. If the female is in poor condition or too thin the egg will not implant.

Bear Mating and Sex

Bears are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. It is not unusual for males and females to mate with different partners each breeding season. On this subject bear researcher Lynn Rogers told Smithsonian, "By our standard, it's pretty sinful, but if a male stayed in the same territory with a female, he'd be competing for food, and that wouldn't be good for the little ones at all."

Male and female bears generally associate only briefly for mating. Males monitor the estrus condition of females in their home range and will remain close for a few days when females are receptive. Multiple mating is practiced by both sexes. On choosing partners, Minnesota biologist Craig Packer told National Geographic, “Size does matter” though more for male competitions than female preference

Males and females tend to mate in the female's territory. After mating the males tend stay in neutral "buffer zones” between the territories of females. Whether departure from the female's territory is voluntary or enforced is not known. Most fights between bears are between males fighting over receptive females. Older males are particularly aggressive towards younger males. Many male bears have nasty scars from such fights. Most showdowns consist of short fights and ritualized threat displays in which the males size up each other and decide who is dominant without really going at it. The largest male often gets the female not because she necessarily prefers him but rather because he is most effective driving off male rivals.

Bears copulate like dogs, with the male grasping the female around her body with his forelimbs. Often the male bites into the female’s neck while mating. Mating takes one to 20 minutes depending on species and individuals. Sometimes bears will mate several times a day.

Bear Births and Parenting

Bear cubs are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Females give birth to their young in protected areas, often a den. Bears are very small when born, from 90 grams for giant pandas to 680 grams for brown bears at birth. They are born with their eyes and ears closed and are either naked or with only a fine layer of fur.

The gestation period is 240 days for polar bears, 225 days for brown bear, 219 days for black bears. The actual development time of the embryo is actually quite short, ranging from six to to eight weeks. The long gestation times listed above include the delayed implantation period. Almost the entire cycle of gestation, birth and lactation takes place in the den when the bear is hibernating.

Because the embryo development time is short, newborn bears are very small when they are born, typically less than ten percent the size of usual ratios between newborns and mothers. Newborn brown bears can weigh as little as 1/720th as their mothers (230 grams for the infant compared to 200 kilograms for the mother).

During pre-weaning and pre-independence stage provisioning and protecting are done by females. Cub nurse during the hibernation period and the entire metabolic demands of the female must be met by her fat reserves. Cubs stay in the den until they are capable of getting around well, at several months of age. Cubs grow rapidly, polar bears go from 600 grams at birth to 10 to 15 kilograms within four months.

Bear Cubs

Sows give birth to blind, nearly naked, mouse-size cubs in their dens in January or February. As the infants nurse they are kept warm by their mother’s body. The eyes of black bear cubs open at around 40 days. Those of polar bears open at around 10 days. Over time their fur grows and thickens. Most sows raise one or two cubs. Occasionally three are seen.

Sows give birth to blind, nearly naked, mouse-size cubs in their dens in January or February. As the infants nurse they are kept warm by their mother’s body. The eyes of black bear cubs open at around 40 days. Those of polar bears open at around 10 days. Over time their fur grows and thickens. Most sows raise one or two cubs. Occasionally three are seen.

Weaning occurs from 3.5 months for Asian black bears to nine months for giant pandas. There is an extended period of juvenile learning. Young stay with their mother for up to three years, but young of most species disperse after 18 to 24 months. Females are very protective of their young and it is likely that cubs learn about obtaining food and shelter during their extended juvenile time with their mother. Sexual maturity occurs at from to three to 6.5 years old, usually occurring later in males. Growth continues after sexual maturity. Males may not reach their adult size until 10-11 years old. Females reach adult sizes usually around five years old.

Most cubs hibernate together with their mother in the same den in the winter. Until they are weaned, young cubs follow their mothers everywhere and are nourished on milk than is as much as 33 percent fat. Females will viciously defend their cubs. Adult males play no role in the cub rearing process. They sometimes attack, kill and eat cubs. One reason cubs stay so close to their mother is for protection from male bears. In some localities up to 40 percent of cubs are killed by other bears.

The attrition rate among young cubs is very high. Many never make to their second birthday. Many are swept up by rivers, die from hunger or are eaten by other bears. Body weight is a good indicator of whether a cub survive or not. American black bear females sometimes abandon a cub born alone. Scientists theorize they do this because they don’t want to waste their energy on a single cub, whose survival is not assured, and choose to wait for a multiple birth the next season.

Why Do Male Bear Kill Cubs?

Male bears sometimes eat bear cubs but overall infanticide in bears rarely occurs. It is still not fully understood why it takes places. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain why bears kill cubs. [Source: U.S. National Park Service, September 30, 2016]

Increase the Male Bear’s Reproductive Potential: Motivation to mate with a female bear may drive a male to kill her cubs. Female bears will not go into estrus as long as they are nursing. If a female loses her cubs in the spring or very early summer, then she may enter estrus and be receptive to mating. However, bears are promiscuous. A female may mate with several males especially in places with densities of bears, like the Brooks River, so there is no guarantee that a male bear that kills a cub would sire another litter with the mother, nor is there any guarantee that the male bear would even have access to the female. Another more dominant male could appropriate the female for himself.

Reduced Competition: Perhaps some bears view cubs as potential competitors in the future. Through infanticide, a bear can eliminate a competitor at its weakest point. This is one fewer bear that the adult may have to compete with in the future.

Food: Bears will kill cubs for food, so certainly in some situations hunger plays a role. Yet, cubs are sometimes killed and not eaten. There is no “one size fits all” explanation for infanticide in bears. Female bears have been observed killing cubs as well, so the behavior is not restricted to males. Infanticide may be difficult to reconcile from a human’s point of view, but bears exist and behave outside of our moral and ethical boundaries.

Bear Contraception?

Scientists in the U.S. are experimenting bear contraception as a way to deal with problem black bears that would involve injecting the animals with chemicals to ward off reproduction. In 2011, Associated Press reported: The technology is still in its infancy, but two studies by a team of scientists are underway at an animal park in Jackson, New Jersey. Black bears typically mate in the summertime, but an embryo lives in the female’s uterus until late fall before implanting itself in the uterine wall and beginning its two-month gestation. In the meantime, the would-be mother investigates the nutritional environment: If food has been abundant, she will produce more cubs. Litters can range from one to six. A healthy female black bear can weigh more than 200 pounds (90 kilograms), but she produces newborns that are no bigger than kittens. [Source: Associated Press, September 28, 2011]

Dr. Allen Rutberg, a research professor at Tufts University’s Center for Animals and Public Policy in Grafton, Massachusetts, said his team began testing a contraceptive called PZP on six female bears in fall October 2004. The vaccine, made from pig tissue, prevents sperm from attaching to an egg. Since female bears give birth every other year, it will be February before the doctors know whether the vaccine has worked. ``So far there’s been nothing discouraging, but nothing terribly encouraging either,’’ Rutberg said. His work is partly funded by the Humane Society of the United States in part because if contraception doesn’t work often the only alternative to problem bears is to kill them.

Burlington County, New Jersey, veterinarian Dr. Gordon Stull is overseeing the injection of some male bears at the animal park with Neutersol, a chemical that in long-term tests on dogs suppresses sperm production but not testosterone. The researchers think male bears will continue to mate, causing their female partners to ovulate and their bodies to believe, incorrectly, that they are pregnant and females won’t accept other suitors when pregnant. Translating the results of either study into practice is at least a few years off.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025