ONAGERS

onager Onager (Equus hemionus) are also known as hemiones and Asiatic wild asses. About the size of a large pony, they are species in family Equidae (horses and their relatives) in the subgenus Asinus. They were one of the world’s first domesticated animals. They are shown pulling carts in 5,000-year-old images from Mesopotamia and are among the fastest land animals, capable of running 64–70 km/h (40–43 mph) and range over a large area. .

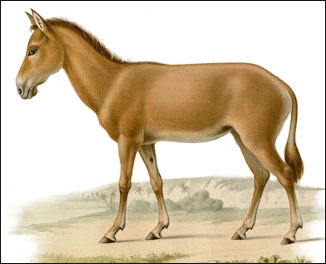

Onagers reach 2.1 meters (6.9 feet) in length, with a 30 to 49 centimeter tail (one to 1.6 foot). Standing about 1.2 meters (3.9 feet) at the shoulder and weighing 200 to 300 kilograms (440 to 660 punds), they are mostly buffy, tawny or gray in color and have a white underside, dark mane, back stripe, ear tips and feathered tail tip. Females and young form loose, wandering herds while young males form bachelor groups. Senior males occupy a territory and fend of rivals with kicks and bites. Onagers eat a variety of vegetation, including grasses and succulent plants, but mostly eat sparse grasses, and herbs that grow along desert edges. In the summer when water is scarce onagers survive by drinking salty water. The maximum lifespan of onagers is around 40 years.

There is some confusion about the onager’s name and taxonomy. The onager is a species with the scientific name Equus hemionus. But they have been included as a subspecies of kulan — the Turkmenistani onager — whereas it should be the other way around. Onagers are commonly known as Asian wild ass — but to be correct that name has traditionally been applied to the Persian onager (E. h. onager). To this day, the name onager can refer to the species onager or the subspecies Persian onager.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List onagers have been listed as Near Threatened since in 2015. Two subspecies is extinct, two are endangered, and two are near threatened; its status in China is not well known. There are only a few hundred onagers remaining in the wild. Today onagers are threatened by loss of habitat, poaching and competition from grazing animals. About 800 onagers live in four remote desert areas of Iran. The Persian onager, a subspecies of the Asiatic wild ass, is critically endangered. They are primarily found in two protected areas in Iran, with populations estimated to be around 600-700 individuals, according to the National Zoo.

There are three species of wild asses, each with several subspecies: 1) African wild ass (Equus africanus) — subspecies: Nubian wild ass, Somali wild ass, Atlas wild ass (extinct) and Donkey; 2) Onager (Asiatic wild ass, Equus hemionus) — subspecies: Mongolian wild ass or khulan, Indian wild ass or khur, Turkmenian kulan, Equus Persian onager or gur and Syrian wild ass or achdari (extinct since 1927); and 3) Kiang (Tibetan wild ass, Equus kiang) — subspecies: Western kiang, Eastern kiang, Southern kiang, and Northern kiang. See Kiangs Under ANIMALS IN TIBET AND THE HIMALAYAS: DEER, FOXES, ASSES, SNOW FROGS factsanddetails.com and DONKEYS: HISTORY, USES, BEHAVIOR, MULES factsanddetails.com

Onager Subspecies

There are six widely recognized subspecies of the onager, two of which are extinct. They are:

1) Persian onagers (E. h. onager) are also known as gur. They inhabit Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan.

2) Indian wild ass (E. h. khur) are also known as khur. They live in southern Afghanistan, India, southeast Iran and Pakistan

3) Syrian wild ass (hemippe, E. h. hemippus) are extinct. They were the smallest subspecies and also the smallest form of Equidae. They lived in western Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Turkey

4) European wild ass (hydruntine, E. h. hydruntinus) are extinct. They were formerly thought to be a distinct species, but have since been shown to be a subspecies of Onager by genetic studies in 2017. They were found in Europe and Western Asia. The last survivors are thought to have lived in Europe around the Danube until around 4000-3000 B.C.. [Source: Wikipedia]

5) Mongolian wild ass (E. h. hemionus) are also known as khulan. They live in northern China, eastern Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and Siberia. They are a nominate subspecies (a subspecies that were originally described as a species (in this cases kulan) and retain the same name as the species itself). Khulan are smaller than a horse but larger than a donkey, they were once seen throughout Mongolia but now are fewer in number and live in a more limited range. It was estimated that there were 23,000 of them in 2003. Their numbers are believed to have declined at a rate of about 10 percent a year in recent decades primarily as a result of hunting, poaching and bitterly cold winters. Khulan meat is processed into sausage. Herders reportedly are not too upset to see the animals go because they eat grass that herders would like their livestock to eat.

6) Turkmenian kulan (E. h. kulan) are also known as kulan. They can be found in Northeastern Iran, northern Afghanistan, western China, Kazakhstan, southern Siberia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, northern Mongolia, and Uzbekistan. They are one of the largest subspecies of onager: two to 2.25 meters (6.6 – 8.2 feet) in) long, one to 1.4 meters (3.3 to 4.6 feet) tall at the withers, and weighing 200–240 kilograms (440–530 pounds).

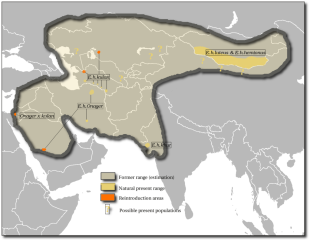

Onager Habitat and Where They Are Found

Onagers are found as far east as China from Mongolia, as far west as Ukraine, as far south as Iraq and as far north as southern Russia and Kazakhstan. Some inhabit northwestern India and Tibet. They have been reintroduced in Mongolia and Iran.[Source: Jill Grogan, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Onagers inhabits deserts, arid regions, grasslands, plains, steppes, and savannahs and favor flat regions of the deserts with surrounding foothills. onager — harsh environments with very little rainfall or water. Because of the harsh conditions that the desert presents, E. hemionus onager must stay within 20 kilometers of a water source.

In the past onagers had a wider range — that included the Levant region and the Arabian Peninsula. The prehistoric European wild ass subspecies ranged through Europe until the Bronze Age. During the early 20th century, it lost most of its range in the Middle East and Eastern Asia and now lives in Iran, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, India, Mongolia and China. Like many other large grazing animals, their range has contracted greatly as a result of poaching and habitat loss.

Syrian Wild Asses

The bones of a Syrian wild ass have been found the 11,000 year-old archaeological site of Göbekli Tepe, Turkey. Cuneiform from the third millennium B.C. report the hunting of'equid of the desert' valued for its meat and hide, which may have been a Syrian wild ass. Although Syrian wild asses were not themselves domesticated, a significant breeding center at Tell Brak produced a hybrid of the wild ass and the donkey, called the kunga, that was an important draft animal in ancient Syria and Mesopotamia. These animals appear in cuneiform inscriptions and their bones are found in burials from the third millennium B.C. The size of these hybrids — larger than modern donkeys and onagers — has led to speculation that ancient Syrian wild asses were bigger than those observed in the 19th century,

Assyrian art from the 7th century B.C. found at Nineveh includes a scene of hunters capturing Syrian wild asses with lassos. Xenophon of Athens mentions Syrian wild asses in his Anabasis, written around 370 B.C.. He reports that they were the most common of animals encountered in Syria; in addition to ostriches, bustards, and gazelles. Xenophon states that horsemen would occasionally chase the asses, with the asses easily able to outrun the horses. He said that asses would only run a short distance ahead of the horses before stopping, waiting for the horses to get closer, and then running ahead yet again. He described the asses as impossible to catch without careful planning. Xenophon also related that the meat of the asses tasted like a more tender version of venison.

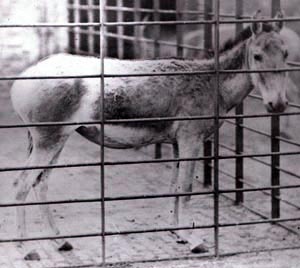

Syrian wild ass in the London Zoo

It is believed Syrian wild asses may have be the "wild ass" that Ishmael was prophesied to be in Genesis in the Old Testament. References also appear in the Old Testament books of Job, Psalms, Jeremiah, and the Deuterocanonical book of Sirach. Surat al-Muddaththir in the Qur’an, the main book of Islam, refers to a scene of humur ('asses' or 'donkeys') fleeing from a qaswarah ('lion'). This was to criticize people who were averse to Muhammad's teachings, such as supporting the welfare of the less wealthy.

European travelers in the Middle East during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries reported seeing large herds of Surian wild asses. Their numbers began to drop precipitously during the 18th and 19th centuries due to overhunting with guns, and in the early 20th century by the regional upheaval of World War I. The last known wild specimen was fatally shot in 1927 at al Ghams near the Azraq oasis in Jordan, and the last captive specimen died the same year at the Tiergarten Schönbrunn, in Vienna.

Donkeys and Onagers in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

Donkeys were among the first members of the horse family to be domesticated. They are believed to have been domesticated from wild asses, or onagers, from Arabia and North Africa about 6,000 years ago.

A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur — dated to 2500 B.C. — shows four onagers (donkeylike animals) pulling a cart for a king. and were supposed to date sometime from 4000 BC. The Sumerians had no camels or horses. They did have sheep, goats and oxen which could be used as beasts of burden. Wheeled vehicles were used as carts. Most were pulled by oxen, onagers or donkeys.

Donkeys and onagers were the main beasts of burden. Goods were moved overland by donkey caravans. Donkeys and onagers later were replaced by horses who are less stubborn, faster, and have a lower threshold of pain (donkey's often do not move even when furiously whipped). The Assyrians and Egyptians used horses and chariots. The Hittites and the Hykos were the first people in the Middle East to use chariots. Chariots came before mounted riders.

5000-year-old Mesopotamian cart in Ur Donkeys appeared in Egypt in the third millennium before Christ and are pictured on old Kingdom engravings dated to 2700 B.C., carrying people and loads in villages and urban areas. In the Old Testament the prophet Balaam was saved by a talking ass, who helped the prophet communicate with an angel he couldn’t see. In the New Testament Jesus made his final entry into Jerusalem on one. In Roman times, Nero's wife is said to have bathed in donkey milk scented with rose oil. Cleopatra also bathed in donkey milk.

Onagers are reported to have bad temperament, which has made them unsuitable as reliable domestic animals. However, the ancient Roman Legions used them animals to pull their war machines. One of their catapults — used by the Roman army during sieges to break down walls and fortifications — was called an onager

Early Carts Carts and Onagers

Animals pulling carts preceded mounted riders by as much as 2,000 years. A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur, dated to 2500 B.C., shows four onanger pulling a cart for a king. The first animals used to pull sledges (carts without wheels) were probably oxen (bulls made more docile by castration). The first carts were probably sledges with logs rolled underneath them.

Over time onangers and donkeys — animals that often will not move even when furiously whipped — were later replaced by horses who are less stubborn, faster, and have a lower threshold for pain than a donkeys. In the second millennia B.C. horses were increasingly to pull weights on the Central Asian steppes. These horses were smaller and shaggier than modern horses, and much more difficult to control than oxen. Deep-furrowed plows also began to be utilized by farmers in the second millennia B.C. Muscular oxen proved to be much better suited for this kind of work than horses.

Herdsman at this time had learned to breed sheep, goats, and cattle, and it follows that they applied what they learned about breeding to horses. Through breeding, horses were made manageable enough to attach to carts with the mouth-fitted bit . By contrast donkeys were controlled by reins attached to nose rings and oxen were harnessed to yokes shaped around their shoulders.

Onager Characteristics and Diet

Onagers reach 2.1 meters (6.9 feet) in length, with a 30 to 49 centimeter tail (one to 1.6 foot). They stand about 1.2 meters (3.9 feet) at the shoulder and weigh 200 to 300 kilograms (440 to 660 pounds), Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females): Males are larger than females..[Source: Jill Grogan, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Onagers are mostly reddish-brown or yellowish-brown in color and have white flanks and underside, dark mane, back stripe, ear tips and feathered tail tip. In comparison with other Asiatic wild asses, onagers are slightly smaller with a paler coat. Onagers’ dorsal stripe has two surrounding white strips that blend into the lighter colored hind quarters. In addition to the dorsal stripe, onagers also have a shoulder stripe. In the winter, the coat grows longer and turns grayer and the white parts become more defined.

Onagers are herbivores that feed on the scarce plant life in the desert. Foods include grasses, bushes, leaves, roots, tubers, wood, bark, stems, seeds, grains, nuts, herbs, fruits and saline vegetation when available. Onagers receive most of their water from their food, but must remain close to a site of open water. When natural water sources are unavailable, the onager digs holes in dry riverbeds to reach subsurface water.

In dry habitats, onagers browse on shrubs and trees, but also feed on seed pods such as Prosopis and break up woody vegetation with their hooves to get at more succulent herbs growing at the base of woody plants. The succulent plants of the Zygophyllaceae is an important component of their diet in Mongolia during the spring and summer Grazing time for onagers is usually during the cooler part of the day such as morning and evening. [Source: Wikipedia]

Onager Behavior

Onagers are cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), terricolous (living in the ground or in the soil), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), solitary, social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups) and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). [Source: Jill Grogan, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Onagers usually lives in herds, with the exception of older stallions, who can be found living alone. Females and young form loose, wandering herds while young males form bachelor groups. Senior males occupy a territory and fend of rivals with kicks and bites. Herd sizes vary, but average herds contain between 10 and 20 animals, sometimes comprised of one male and many females. Under harsh ecological conditions or pressure from predators single male groups may come together.

Onagers sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They have keen senses, especially their sense of smell. Like other members of the genus Equus, onagers have vocal, tactile and chemical communication. In addition, visual signals may be important. Onagers are very fast as we said before, with the ability to run 60 to 70 kilometers per hour (37 to 43 mph) over short distances, and 40 to 50 kilometers per hour (25 to 31 mph) for several hours at a time. ~

Onager Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Onagers are polygynous (males having more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding, usually in mid-June. Onager mares breed every other year. The number of offspring is one and the gestation period is one year. [Source: Jill Grogan, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

A dominant stallion mates with females in the herd. In order to assure breeding status, stallions defend the territories that females move through, with dominant stallions defending the best territories. During the mating season stallions fight each other for mating rights. Females have a short estrus period of three to five days.

Mares leave the herd to give birth in a safe place. After giving birth, both mare and foal rejoin the herd, where the mother protects her foal from danger. Young are precocial. This means they are relatively well-developed when born. All members of the genus Equus are fairly precocial at birth, and are able to run shortly after birth.

During the pre-weaning stage provisioning and protecting are done by females. Pre-independence protection is provided by females. The age in which they are weaned ranges from 18 to 24 months and the average time to independence is two years.The position of the mother in the dominance hierarchy affects status of young. /=\ On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 2 years. Males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at two to four years.

Two subspecies of onager are extinct, two are endangered, and two are near threatened; its status in China is not well known. There are only a few hundred onagers remaining in the wild. Today onagers are threatened by loss of habitat, poaching, hunting and competition for food and water from grazing animals and livestock. About 800 onagers live in four remote desert areas of Iran. The Persian onager, a subspecies of the Asiatic wild ass, is critically endangered. They are primarily found in two protected areas in Iran, with populations estimated to be around 600-700 individuals, according to the National Zoo.

Onager Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List onagers have been listed as Near Threatened since in 2015. Before that they were listed as Critically Endangered. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. [Source: Jill Grogan, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Adult onager have no natural predators other than humans due to their large size, speed and lack of predators in the harsh places they live. Young may be preyed on by wolves or foxes. Onagers have a well developed sense of smell and can detect potential predators, from a far distance.

In 1971, Persian onagers became a protected species in Iran and hunting them is prohibited year-round. In the early 2000s, the IUCN estimated there were 144 Persian onagers remaining and the they had declined by 28 percent over the last three generations.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025