MUSLIMS IN CHINA

Islam reached China in the mid-seventh century through Arab and Persian merchants travel the Silk Road and sea routes to southern China. The religion has a large following among ten of China’s minorities: Hui (Muslim Chinese), Uyghur, Kazak, Tatar, Kyrghyz, Tajik, Uzbek, Dongxiang, Salar, and Baoan. They live mostly in Xinjiang, Gansu, Ningxia, Yunnan and Qinghai. There are thriving communities of Hui in all regions of China, namely the areas mentioned before and Inner Mongolia, Henan, Hubei, Shandong, Liaoning, Beijing and Tianjin.

According to the official website of the State Administration for Religious Affairs, there are about 35,000 mosques in China. Most Muslims in China are members of the Uyghur and Hui nationality people. Islam is one of the officially sanctioned religions. Community-funded mosques, prayer rugs and even a few veiled women can been seen in the barren deserts and stony mountains of western China; the Silk Road cities such as Turfan, Kashgar and Khotan; and villages and towns in Ningxia Province and parts of Gansu Province and Inner Mongolia..

Ninety-nine percent of the Muslims in China are Sunni, divided into a number of sects.. The other 1 percent are Shiites. Most of them are Tajiks. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ Sufi orders entered through northwest China during the Qing and were proscribed by the government in late Qing because of their tie to the Muslim rebellions in the area. Because of its identification with some of China's largest minority groups, Islam appears to have been less restricted than other major religions after the 1949 Revolution, but even so the authorities closed a number of mosques and schools and restricted the training of clergy. Since the post-Mao reforms, the government has allowed mosques to reopen and the number of active followers has been growing. Conversion by Han Chinese comes mainly through intermarriage, since the state views Islam as a religion of the shaoshu minzu (minority nationalities) rather than a universalist creed. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Many ordinary Chinese regard Islam as backward and oppressive. Muslim groups in China have traditionally not been very religious. Islam for them has been more of cultural badge than an ideology to live by. Although many Chinese Muslims don’t eat pork many drink alcohol and neglect their daily prayer duties. In some places in western China, Muslim women wear veils, not for religious reason, but to keep out the dust.

See Separate Articles: CONTROL AND REPRESSION OF ISLAM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG EARLY HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG AND CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG SEPARATISM AND HUMAN RIGHTS Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG RIOTS IN 2009 Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG, URUMQI Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG. KASHGAR Factsanddetails.com/China ; See Islam in Suzhou Under SUZHOU AND ITS AMAZING GARDENS factsanddetails.com and Islam in Xian under XIAN: ITS HISTORY, FOOD AND TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com and Linxia under GANSU PROVINCE: LANZHOU AND NEARBY BUDDHIST AND TIBETAN SITES factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ;Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Websites and Sources on Religion in China: : United States Commission on International Religious Freedom uscirf.gov/countries/china; Articles on Religion in China forum18.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy stanford.edu ; Academic Info academicinfo.net ; Internet Guide to Chinese Studies sino.uni-heidelberg.de

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Islam: “Islam in China” by James Frankel Amazon.com; “Islam in China” by Mi Shoujiang, You Jia, et al. Amazon.com; “China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law (Cambridge Studies in Law and Society) by Matthew S. Erie Amazon.com ; Muslims “Ethnic Identity in China: The Making of a Muslim Minority Nationality” by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “Ethnographies of Islam in China” by Rachel Harris, Guangtian Ha, et al. Amazon.com; “Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “Travels through Muslim China (2005-2012): A Muslim Woman's Discovery of Chinese Mosques” by Sophie Paine Amazon.com; “Muslim China - A Photographic Recollection (2005-2012)” by Sophie Paine Amazon.com; “Dislocating China: Muslims, Minorities, and Other Subaltern Subjects” by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “China's Muslims” (Images of Asia) by Michael Dillon amazon.com ; “Muslims in China” by Aliya Ma Lynn Amazon.com; History “Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China”by Jonathan N. Lipman Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “The Muslim Merchants of Premodern China: The History of a Maritime Asian Trade Diaspora, 750–1400' by John W. Chaffee Amazon.com; “The Dao of Muhammad: A Cultural History of Muslims in Late Imperial China (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Zvi Ben-Dor Benite Amazon.com; “Islamic Thought in China: Sino-Muslim Intellectual Evolution from the 17th to the 21st Century” by Jonathan N Lipman Amazon.com; “The Panthay Rebellion: Islam, Ethnicity and the Dali Sultanate in Southwest China, 1856-1873 by David Atwill Amazon.com; “Holy War in China: The Muslim Rebellion and State in Chinese Central Asia, 1864-1877" by Hodong Kim Amazon.com; “China's Muslims and Japan's Empire: Centering Islam in World War II” by Kelly A. Hammond Amazon.com; “Muslim, Trader, Nomad, Spy: China's Cold War and the People of the Tibetan Borderlands (New Cold War History)” by Sulmaan Wasif Khan Amazon.com

Muslim Numbers in China

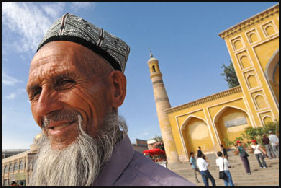

Uighur Muslim outside

a mosque in Kashgar Muslims are the largest identifiable religious group in the country. About a third of them live in Xinjiang. They are found in small communities all over China but only in large numbers in the extreme west and northwest — -the eastern extreme of the Muslim world. There are around 30,000 mosques in China, with 23,000 of them in Xinjiang. The Great Mosque of Xian is one of the of the oldest and biggest in China. First built in A.D. 742, it is used by the 60,000 Muslims in Xian. There are more Muslims in China than in Saudi Arabia and most Muslim countries. Hui Muslims are concentrated primarily in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Qinghai, Gansu, and Yunnan provinces. Uyghur Muslims live primarily in Xinjiang. [Source: “International Religious Freedom Report for 2013 China”, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, U.S. Department of State, state.gov ]

According to the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA), there were 21 million Muslims in China in the late 2000s; unofficial estimates range as high as 50 million. According to the report on Mapping on the Global Muslim Population conducted by Pew Research Center (2009), there are 22 million Muslims in China. A report on International Religious Freedom conducted by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (2006) said "there were 20 million Muslims, more than 40,000 Islamic places of worship (more than half of which are in Xinjiang), and more than 45,000 imams nationwide." The same report also said that about half of the Muslims in China belong to the Hui minority. [Source: Ali Osman Ozkan, Fountain magazine, April 2014]

Officially there are around 26 million Muslims in China based on the 2020 Chinese census but this count is based defining Muslims as being members of an ethnic group with the assumption that all Hui and Uyghurs, two Muslim groups in China, must be Muslims. Matthew S. Erie told the New York Times:“It’s a problematic issue because it’s an ethnic category that is used to define members of a religion. Hence, it can be both over-inclusive and under-inclusive. For the former, Muslims outside of China may not consider every Hui to be a Muslim. Many Hui are very pious. They attend mosque regularly and go to the hajj. And then there are people who say they’re Hui, meaning they just don’t eat pork. For the latter, it’s possible that some Chinese citizens who are ethnically Han [the dominant ethnic group in China] or Tibetan are, in fact, Muslims. It’s a very loose category.[Source: Ian Johnson New York Times, September 6, 2016. Matthew S. Erie, a trained lawyer and ethnographer who teaches at Oxford University, lived for two years in Linxia and , a small city in the northwestern Chinese province of Gansu. Known as China’s Mecca, it is a center of religious life for the Hui. Mr. Erie’s book, “China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law,” explores how Shariah — Islamic law and ethics — is implemented among the Hui.]

Muslim Minorities in China

The ten Muslim minorities of China are categorized by their ethnicity. Six of the nine Muslim minorities—the Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Tatars and Tajiks—live predominantly live in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. They all speak Turkic languages, except the Tajiks who speak a Persian-based language. The Huis are found throughout China. The remaining three Muslim minorities— the Salars, the Boa'an, and the Dongxiang, live in different regions. The Salars are another Turkic speaking Muslim minority in China that live in a region that borders the Gansu and Qinghai provinces. The Salars trace their ancestry back to people who migrated from the Samarkand region during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The Boa'an live in the southwest of the Gansu province, while the Dongxiang live in the western-edge of Gansu province. Both trace their ancestors back to the Asian troops sent out during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). The Boa'an and Dongxiang languages also originate from the Mongolian language family, even though they are different from each other.

Muslim Groups in China: See Separate Articles:

HUI MINORITY: NUMBERS, IDENTITY AND RELATIONS WITH CHINESE factsanddetails.com ;

HISTORY OF THE HUI AND HUI ISLAM factsanddetails.com ;

HUI LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ;

UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com ;

UYGHUR LIFE, MARRIAGE, HOMES AND FOOD factsanddetails.com ;

UYGHUR CULTURE. LITERATURE, KNIVES AND HIP HOP factsanddetails.com ;

KAZAKHS IN CHINA: HISTORY AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ;

KYRGYZ IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

TAJIKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

UZBEKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

DONGXIANG MINORITY factsanddetails.com ;

SALAR MINORITY factsanddetails.com ;

BONAN MINORITY factsanddetails.com ;

TATARS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Islam in China in the 2010s

Early History of Islam in China

Islam was introduced to western China by missionaries and traders traveling on the Silk Road and to the ports of Canton and Hangzhou by mariners traveling on trade routes around India and Southeast Asia. The first Muslim missionary to arrive in China purportedly was an uncle of Muhammad who arrived in Canton in A.D. 627. Some of the first arrivals made it Changan (present-day Xian), the Tang Dynasty capital and starting point of the Silk Road. The Great Mosque of Xian was built on A.D. 742.

Islam first appeared in China in the 7th century in the Tang Dynasty (618-907), following the emergence of Islam in Arabia in 610. Arab and Persian traders, soldiers and Sufi saints played a significant role in the transmission of Islam to Asia. Persian and Arab traders first settled in the southeastern coast of China, Canton (Guangzhou,) Xiamen, Quanzhou, Yangzhou, and some of them married local Chinese. They were few in number are were largely ignored by local officials during Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1279). [Source: Ali Osman Ozkan, Fountain magazine, April 2014]

Islam spread in China during the Yuan Dynasty (1368-1644) because the Mongol rulers forced many Muslims living in Central Asia and Western Asia to migrate to China. The “armies of Genghis Khan and his successors sacked major Islamic centers, including Bukhara and Samarkand, and transported sections of the population-skilled armourers, other craftsmen, and enslaved women and children among them-back to China, where they were settled as servants to Mongol aristocrats" (Dillon, 1996). In addition, the Mongol rulers of China made legal and hierarchical distinctions between the four kinds of people that led the Muslims to have higher status than the Chinese because the Muslims succeeded the Mongols who were at the top level (Gladney, 1996). Some Mongol generals during the Yuan dynasty were Muslims.

Islam had different names at different time in China. In the Tang and Song dynasties, it was called "Dashi Law" and "Dashi religion"; in the Yuan dynasty, it was called "Huis Law" and the "Huis style"; in the Ming dynasty, it was called "Huis denomination" and "Islam"; while in the Qing dynasty, it was called "Arabian religion" and "Islam", and so on. After the founding of Communist China in 1949, the State Council issued orders for it to universally be called Islam. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

At the end of the Ming dynasty and the beginning of the Qing dynasty, Islamic Sufi mysticism was widely spread throughout China. At the end of the Qing dynasty and the beginning of the Republic of China, the Yihewani Movement of "respecting scripture and reforming custom" emerged, the Beijing-endorsed Islam was divided into three denominations—Gedimu, Yihewani and Xidaotang— and four official schools— Zhehelinye, Gadelinye, Hufuye and Kubulinye, with more than 40 branches. ~

See Separate Article HISTORY OF THE HUI AND HUI ISLAM factsanddetails.com ;

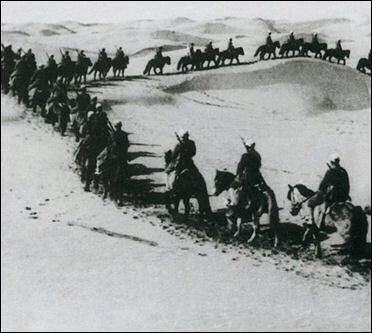

T.V. Soong at a mosque in Xining in 1934

Contributions of Islam to China

Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: “Little acknowledgment is given to Muslim contributions to Chinese civilization. After the decline of Chang’an and the Tang Dynasty (618-906), when Baghdad, the seat of the Islamic empire, became the new cultural center of the world, Muslim scholars and artisans brought China advances in medicine, mathematics, astronomy and the arts, from metalwork and glassware to the cobalt pigments that would become the signature of Chinese porcelain.” [Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

Alessandra Cappelletti wrote in The Conversation: “From written records and imperial edicts engraved on steles (standing stone slabs monuments) it is clear that these Islamic communities enjoyed the favor of the emperors — especially during the Tang (618-907 AD), Yuan (1271-1368), Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties. Islam was looked on favorably by the imperial court because of its ethics, which — as far as the emperors were concerned — promoted harmonious and peaceful relations between the diverse peoples in the imperial territories. [Source: Alessandra Cappelletti, The Conversation, March 12, 2021]

Before the Panthay and Tungan rebellions in the second half of the 19th century in western China, when millions of Muslims were killed or relocated, Islam was considered by Christian missionaries in the country — and particularly by Russian scholars — as a growing threat. Islam was considered by many in the west to have the potential to become the national religion in China — which would have made China the biggest Islamic country in the world.

Rebellions and the Slaughter of Muslims in China

During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) there were armed uprisings of Muslim ethnic and religious movements in Shaanxi and Gansu (1862-1875), and the “Panthay" Muslim Rebellion in Yunnan (1856-1873). Even after the status of Xinjiang was changed from a military colony to a province in 1884, Muslim resistance continued until the end of the dynasty. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Possibly millions of people were killed when the Chinese Imperial army cracked down on two Muslim rebellions mentioned above. In addition to being brutally put down, the revolts gave China an excuse to gain control over territory occupied by the Muslims.

A Muslim uprising in 1855 was the result of a dispute between Muslims and Han Chinese over the ownership of some gold and silver mines. In 1863, a Muslim sultan named Du Wenxiu established the Muslim kingdom of Nanping Guo in Dali, which lasted until 1873 when it was overrun by Qing forces. Du Wenxui was tortured and executed after a suicide attempt failed.

See Separate Article HISTORY OF THE HUI AND HUI ISLAM factsanddetails.com ;

Hui family celebrating Eid

Later History of Islam in China

In 1953, the Chinese Islamic Association was established with Burhan Shahidi as its chairman. Many mosques and other buildings associated with Islam were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. With the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, the Chinese government's shift in its attitude towards the practice of religions certainly enabled the revival of religious institutions and the free practice of religions in China.

In the mid-1980s, there were 15,800 religious professionals, about 2,000 of whom were either deputies to the People's Congress or the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference at various levels, or worked in the regional or county branches of the Chinese Islamic Association. At that time China boasted a total of 15,500 mosques or prayer centers, or one for almost every Muslim village. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Even though they were tormented along with many other groups during the Cultural Revolution, Muslims for the most part have been allowed to practice their religion and culture without interference from the Communist Chinese government. Even so many opportunities have been denied them. Very few Chinese Muslims, for example, have had the chance to go to Mecca. As of the late 1980s, out of the hundreds of thousands of Muslims who lived in Inner Mongolia only one had been to Mecca, and he was sent by the government.

The Chinese government has encouraged Muslims, particularly Huis, to move to Tibet. The presence of these Muslim was one of the triggers for the riots in 2008 that left at least 22, and maybe a lot more, dead. In 2012, China moved 17,000 mostly Chinese and Muslim settlers to a traditionally Tibetan region in western China, reviving a plan abandoned after protests by critics of China’s Tibetan polices.

Growth of Islam in China

The number of mosques in China grew from 20,000 in 1994 to 34,000 in 2010. Many view this as solid evidence that Islam is growing in China. Matthew S. Erie told the New York Times: “The vacuum created by the end of Maoism has led to a commercialization of Chinese society that is in its own way spiritually void. There’s no question that people are searching for meaning. What’s really important is that some people are doing it through Islam. These are people who were born Hui but not part of that spiritual tradition, and who are returning to it. They find a group of fellow believers and discover strength in that community. Many of these people travel to places like Linxia and study Islam for the first time in their lives.

mosque in Guangzhou

“The region from Lanzhou to Linxia is often called the Quran belt. When you’re on the highway, it’s impossible to go a minute without seeing a new mosque under construction. What’s driving this is an accumulation of wealth, and people are willing to allocate some of it, because they see mosques as a center of their community. It’s not just where people pray or study but also where they socialize and share news and gossip.

Almost none of it is government-financed. “.Almost all comes from donations. Donors are businesspeople using the money they’ve saved to benefit their communities.” Overseas donations like that from the Saudis or Gulf states used to build big mosques in the West “rarely happens in China. The government keeps tight control over this. They don’t want to have these sorts of ties overseas.

“The revival has two aspects. One is almost always personal: a marriage that didn’t work out, or interfamilial strife. And then they learn about larger phenomena through translated texts, social media or on-the-ground missionary activity. Saudi Arabia is a natural pole star. Egypt has major pull given its academic institutions and religious scholars. Missionary work increasingly comes from the Dawa movement. These activists are primarily from South Asia. The idea is that Muslims should return to the pious behavior of the Prophet Muhammad. This can mean a variety of things, from daily prayer to rejecting chopsticks in favor of eating with one’s hands. These people interact with the Hui trying to find themselves. That’s where the rekindling occurs.

Some of this seems to parallel Christianity’s rise in China. “but Islam is different in that you have this global discourse on terrorism, which is oppressive and limits the capacity of Muslims inside China to interact with Muslims outside of China. Islam is so politicized that it’s quite different.

“There are converts, for sure. The motivations are interesting. I met a Han laborer who worked on the railway. He had injured his arm and did not receive benefits. He became disaffected and found solace in Islam. He was also looking for a wife. Poor Han men sometimes convert if they’re looking for a wife, because there are Hui networks that will help out. Hui will help you convert and marry. But changing one’s ethnic identity, officially, is very difficult. It can happen, but it’s hard.

Chinese Islamic Beliefs

Many Islamic branches in China have traditionally had links to Sufism. These branches had strong links to their founders and the philosophies and ideas embraced by the founders. Sometimes regarded as saints, these founders were not only spiritual leader, but also political leaders of the followers of the official branches. Followers not only revered these founders while were alive, they were worshiped at grand tombs and shrines built after their death.

Minaret in Turpan Ali Osman Ozkan wrote in Fountain magazine, “Muslims in China believed that Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, the maternal uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, along with the three companions of the Prophet, were the first Muslims in China. In accordance with this claim, He Qiaoyuan, a seventeenth century Chinese scholar, also stated that "the prophet's four apostles arrived in China to preach during the middle of the reign of Emperor Wude in the Tang Dynasty" (Sen, 2009). At the same time, many Chinese Muslims pay visit to a tomb which is associated with Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas in Canton (Guangzhou). Today there are even some Chinese Muslims who trace back their ancestry to Abi Waqqas. However, contemporary scholars regarded that this chronicle was a legend due to the lack of evidence. Instead, they argued the beginning of Islam in China started with the envoy sent by Caliph Usthman, in the Tang Dynasty, in 651 (Sen, 2009).

“The Han Kitab is a collection of treatises, translations and books constructed by different Chinese Muslim scholars between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries. Wang Daiyu, Ma Zhu, and Liu Zhi are the most well-known authors of the Han Kitab. The authors of the Han Kitab took an unprecedented position in the history of Islam in China by using predominantly Neo-Confucian terms in the introduction and description of fundamental Islamic concepts such as prophethood, God, and ritual. The Han Kitab is the very example of the adaptation of Muslims into Chinese culture. For example, the concept of prophethood in Islam, is explained with the Neo-Confucian concept "shengren" which means "a link in the long chain of sages sent by Heaven to communicate the Way through their worldly teaching" (Frankel, 2011, p.88). In short, the authors of the Han Kitab are mainly concerned about making abstract Islamic terms more understandable by using the existing religious terminology in China.”

Chinese Muslim Funerals and Burials

Most Chinese Being Muslims, strictly abide by the basic Islamic funeral principles of "burial in the ground", "thrifty and simple burial" and "quick burial". Muslims believes that the a human being is created by the "soil" of the land and thus he should be returned back to the soil when he dies. Burial in the ground after death is to return to one’s birthplace. Chinese Muslim often say "burial in the ground after death is safe" and "burial in soil is like that in gold". They avoid cremation, and do not use inner or outer coffins when burying the dead people in the ground.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Hui Prayers Dongguan mosque The custom of burial in the ground is very simple: 1) select a place at the cemetery, 2) then dig a pit that is about one meter in width, two meters in length and two to three meters in depth in a south to north direction, 3) and then dig a wing-hole on the western pit wall. 4) When the dead person is buried, the head of the corpse is placed in the north direction. The face is placed in the wing-hole so that it faces west towards Mecca. 5) The entrance of the hole is sealed by adobe bricks and mud, 6) then the pit is filled with soil until a grave mound forms on the surface of the ground. Wood boards, stone boards and iron boards and other non-soil items, baked porcelain articles or other grave goods are strictly forbidden in accordance with Muslim burial rules. Most Muslims also frown on the construction of grand, large-scale tombs, although sometimes exceptions are made for revered Muslim saints, and forbid the building of houses on tombs. ~

Islam advocates a thrifty and simple burial, and holds that the funeral should conform to the principle of simplicity, eliminating unnecessary and overly-elaborate formalities. It is particularly critical of anything that hints of ostentation or extravagance. Behind this is the belief that when a human being is born, he is bare and has nothing, so after death, he should also be buried under the same terms. After the death of a person, only an imam is invited to chant scriptures, while family members or funeral specialists wash the corpse with clean water, dress it in a "kafan" (a white cloth and twine used for wrapping the corpse, for women corpses, a cloth to cover the head is added). A corpse needs no any other clothing. Then the corpse is moved into the "tabu" (a rudimentary coffin-like wooden box for carrying corpse in the mosques), and a simple and short funeral is held. Then the corpse is carried to the graveyard and buried in a prepared tomb. During the time of waiting for and holding a funeral, people are forbidden from crying loudly, making an uproar, sending wreaths and funeral couplets, setting off firecrackers, hammering gongs and beating drums, or using any other musical instruments. It is forbidden to create spirit or ancestor tablets as is the custom of Chinese and put up portrait of the deceased. Making sacrifices or presenting offerings is also not allowed. ~

On the topic of quick burials, the prophet Mohammed said: "you should bury the dead people quickly, if they are happy, they should gain the happiness as early as possible; if they are not lucky, you should let them evade the fire and prison as quickly as possible." Therefore, Islam provides that all Muslims "must be buried within three days after their death" preferably within 24 hours. Islam opposes the custom of waiting for an auspicious lucky day as extravagant and wasteful. Most Muslims try to hold the funeral on the day of the death, not waiting for the next day. Only when the time of death is very late, or some other special situation happens, or close kin of the dead person are far away and cannot return home quickly for the funeral, can the rule be broken to wait for a day. For guiding principal for a quick burial is "the soil in any place can bury people". The dead can be buried anywhere they die. It is not necessary to transport the corpse a long distance to a hometown for a burial. Additionally, it is not necessary to bury the dead together with their ancestors in the hometown as is the custom among Chinese. ~

Simple funeral Muslim practices are observed by the Baoan, Hui, Dongxiang, Salar and other Islamic minorities in China. They believe that a thrifty, simple and quick burial, not only save times and manpower, it also avoids wasting of wealth, and helps prevent the spread of diseases and environmental pollution. ~

Muslim Festivals in China

Ma Jia Jun Army

Corban is a Muslim festival celebrated in western China 70 Days after Ramadan by Islamic ethnic groups like the Uygurs and Kyrgyz. Also known as the "Livestock Sacrificing Festival," it commemorates the day that Abraham had a dream in which God told him to kill his son as an offering. Just as Abraham was about ready to do this, God intervened and told him to sacrifice a sheep instead.

Muslims begin Corban by washing themselves and visiting their local mosque. Later a sheep is sacrificed by slitting its throat. The animal is then skinned and carved up and eaten. Whatever is left over is given to the poor. The Tajik, Kyrgyz, Uzbek and Keerkezi people like to celebrate this holiday with horse racing, sheep snatching and wrestling.

The Kyrgyz enjoy the "girl chasing game," in which a boy and a girl, both on horseback, enter a designated area, where the girl whips her horse and takes off with the boy in pursuit. Whatever jokes the boy makes and however mercilessly he teases her the girl must put up with it. On the way back, however, it is the girl's turn to chase the boy. If she catches him she is allowed to hit him with her whip and he can't hit back. If the girl likes the boy she will just pretend to hit the boy. But if she doesn't like him she can hit the boy as hard as she wants. Many Kyrgyz marriages begin this way.

In the "sheep snatching game" a sheep is placed in a designated area. Men on horseback ride to the area and try to grab the sheep, fighting off one another, and carry the sheep to another specified place. After its over the sheep is cooked into "Eating Happiness Mutton" and consumed.

Islamic Clothing in China

The Hui, Dongxiang, Salar, Baoan and other Islamic ethnic groups in China often wear clothing that distinguishes their Islamic beliefs and ethnic identity. It is said that Mohammed was fond of white clothes. Some say he told his followers: "You should often wear white clothes, because white clothes are the purest and most beautiful." Many Hui, Dongxiang and other Muslims wear white hats, headscarves, shirts and even trousers. When people die, their corpses are wrapped in white cloth, showing "coming purely and leaving purely". It is a taboo for corpses to be wrapped in colored cloth or silk.

Chinese Muslims believe their headgear is related with Islam. Because the Islamic praying— one of the "five pillars” of Islam— demands the worshipers not expose their heads, they must cover them, and touch their foreheads and tips of noses to the ground when they bow towards Mecca. If they wear hats with brims, the forehead and tip of nose cannot touch the ground. Only small white hats with no brims and skullcaps allow worshippers to do this.

Female headscarves conform with the Koranic provision: "You tell the female followers to lower their line of vision, cover the lower part of the bodies, not to show the jewels, unless the natural. Tell them to use the veil to cover their chest, not to show the jewels, unless to their husband, father or sons." Though few Muslim women in China wear veil, many wear headscarves that cover their hair, ears and neck. These not are not only in accordance with Islamic doctrines, they also have become unique clothing of the ethnic groups that wear them. Decorations and patterns found on the clothing of the Hui, Dongxiang and other Islamic minorities rarely has figures or animals, but rather has flowers, geometric patterns and Arabic calligraphy because Islam forbids the worshiping idols and displaying images of people and animals is seen as trying to do the work of god.

Shariah in China

Matthew S. Erie, a trained lawyer and ethnographer who teaches at Oxford University, lived for two years in Linxia, a small city in the northwestern Chinese province of Gansu. Known as China’s Mecca, it is a center of religious life for the Hui. Erie’s book, “China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law,” is a look at how Shariah — Islamic law and ethics — is implemented among the Hui. [Source: Ian Johnson New York Times, September 6, 2016]

Muslim schoolboys

In the West, people often think of Shariah as a rigid Muslim legal system from the Middle Ages, with stoning and amputations. But in reality it is something alive and very flexible. Erie said: “The parameters are wide, from dietary considerations to interpersonal relations. Some of it is deciding what is halal food. But it’s also what we would call torts in the U.S. — when someone driving a vehicle strikes a pedestrian. A lot of time the authorities will ask the mosques to aid in evidence-gathering. We have a localized sense of Hui morality, that may be inflected with Shariah and that might affect the outcomes — the amount of the settlement, for example. The ahongs [Hui term for cleric] will help determine an amount.

It’s not used in criminal law, where the state has the monopoly on using its own legitimated force. But in social relations, the Hui are part of this local dynamic — the clerical authority and the authority of the local state...The state realizes it needs the local clerics. If the state were to consciously exclude the local religious authorities, it would lose legitimacy in the eyes of the believers.

“There is a spectrum of opinions” on how the Hur and other Muslim groups in China feel about this. “They push for more autonomy and decision-making ability but are not always allowed to. In this, I think their struggles parallel those of Muslim minorities elsewhere — in France, Germany or the U.S. — but in China they do not have recourse to formal law, political institutions or even civil society. Rather, they rely on their ties to the government and increasingly transnational networks to protect their personal and collective interests.

Islamic Education in China

Because the Hui mainly live together with Han Chinese, they generally attend Han Chinese schools where they receive the same education as ordinary Chinese. Those that want religious training or an Islamic education is supposed to pursue it through Beijing-sanctioned mosques, referred to by the Chinese government as “scripture auditoriums.” [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

“Scripture auditorium education” is also called "temple education" and "the Huis College". "Scripture" refers to the scripture of Islam, "auditorium" refers to "mosque" (in the Tang dynasty, people called mosques "auditoriums"). In the old days, an Islamic teacher recruited some students and taught them Arabic letters, phonetic letters and basic knowledge of Islam, then the students were transferred into a madrassah ("college"), where Arabic grammar, rhetoric, the Koran, and Islamic doctrines were systematically taught and studied. Generally, the students studied there for three to five years; during the time, Muslims near the mosque supplied the student’s clothes, food, shelter and transportation. After completing the courses, they would "wear the clothes and hang the curtain" and were qualified as Islamic teachers.

However, if Muslims wanted to become officials in the imperial Chinese system they needed to get to learn Chinese and Confucianism and the Classic and do well on the civil service exam. Under these terms upper-level Huis and other Muslim figures and their children attended private Chinese schools, or entered the "academies" and "the Imperial College" to study the classic Han curriculum. In the Yuan dynasty, many Huis began their official career by imperial examinations, or became famous intellectuals, officials poets and artists. In the Ming dynasty, general education became more universal. During this time, more and more Hui and Muslim scholars, officials and writers emerged, such as the statesmen Ma Wenrui and Hai Rui, the thinker Li Zhi, the poets Ding Henian, Jin Dache and Jin Dayu.

Fourteen Killed in China Mosque Stampede

In January 2014, Associated Press reported: “A stampede broke out during an event at a mosque in northern China, killing 14 people and injuring 10 others. Worshippers at the Beida Mosque in Guyuan, a city in the Ningxia region, were handing out traditional cakes during an event to commemorate a religious figure afternoon when a rush for food triggered the stampede, Xinhua said. It quoted a witness as saying people trampled over each other.[Source: Associated Press, January 6, 2014]

“This year's event had a record number of participants as it fell over the weekend, Tan Zongzhi, the head of Xiji county's religious affairs bureau, was quoted as saying. A meeting of the Ningxia Communist Party committee blamed poor organization and insufficient management for the stampede, according to Xinhua. Four of the 10 people hospitalized were in critical condition, Xinhua said. Ningxia is the home of China's Muslim Hui ethnic minority.

Women-Only Mosques in China

Cui Jia wrote in the China Daily, “It was still dark at 6:25 am on a late October morning in Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu province. Carefully gripping the handrail, Ma Guifang, 80, slowly climbed the stairs to the prayer hall on the second floor of Lulan women's mosque for morning prayers, her aching knees protesting at the ascent. or the past 20 years, the elderly lady from the Hui ethnic group has been attending this women-only mosque, a phenomenon unique to China. "I feel so blessed to have a mosque I can visit. Not many female Muslims enjoy such a privilege," she said. [Source: Cui Jia, China Daily, November 20, 2012 /~/]

“Lulan women's mosque was built in 1956 by a group of female Muslims who had relocated to Lanzhou from Henan province in central China. Muslim schools for women enjoy a long history in China, having first been established during the latter half of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). They developed into women-only mosques, presided over by female imams, during the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The practice of female imams quickly spread within China's Muslim groups, according to Shui Jingjun, a researcher at the Henan Academy of Social Sciences, who published a book on the history of women's mosques in China in 2002. /~/

“Women's mosques soon began to proliferate in China's central plains, mainly in the provinces of Henan, Hebei, Shandong and Anhui. In the northwestern provinces of Qinghai and Gansu and the Ningxia Hui and Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous regions, the public participation of women in ritual and leadership is much more restricted, so there are fewer examples of mosques such as this in those areas, added Shui. For example, Lulan is the only women's mosque in Lanzhou, but there are 19 in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province. /~/

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see chinadaily.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, CNTO, Nolls

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022