UYGHUR CULTURE

The Uyghurs have produced sophisticated literature, with short stories, love poetry, oral narratives, historical-narrative songs, and epic folk legends called dastans. Wolves pop up frequently in Uyghur folk stories. Some consider Uyghurs to be the originators of movable type printing. Archeologist have found Buddhist sutras printed in the Uyghur language that date back to the 10th century.

Ancient Uyghur cave paintings featured images of Buddha and bodhisattvas. After converting to Islam, Uyghur craftsmen became well-known for producing plaster carvings and embroidery with geometric forms, arabesques and plant motifs.

Classical Uyghur music is a Turkic style and are influenced by Persian and Arabic traditions. There are specific folk music for specific occasions. Uyghur musical instruments include the long-necked, stringed rawap. The twelve Mukam and Thirteen Melodies for String Instruments is regarded as classic of Chinese folk music.

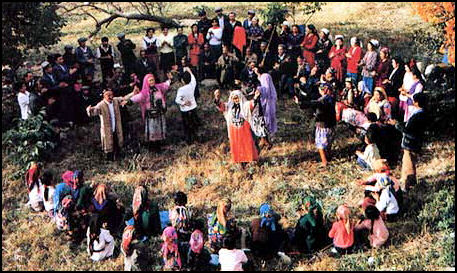

Uyghurs are excellent horsemen. Uyghur festivals feature horse races. tightrope walking acts, field hockey like game, and two-story-high swings big enough for two people too stand and swing into the trees. Most participants in traditional Uyghur dances and singing sessions are women. Uyghur women perform the Picking Grapes dance dressed in dorhas and red dresses. Western pop music is popular among the young. Dog fighting is a popular sport. Pit bulls are used.

People of Xinjiang have the right to use their native languages in broadcasting. There are Uyghur-language broadcast on Radio Free Asia. The content often has an anti-Chinese slant. The Chinese government often jams the signal. The film Patton was popular among Uyghur intellectuals. They were particularly moved by the anti-Communist speeches.

In cities such as Hotan, young Uyghur couples dance at discos. James Miflor, a professor at Georgetown and expert on Uyghurs, told National Geographic, “In the cities they are modern and worldly.”

See Separate Articles: UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com ; UYGHUR LIFE, MARRIAGE, HOMES AND FOOD factsanddetails.com ; UYGHURS, CHINESE AND ECONOMICS factsanddetails.com ; UYGHUR SOCIAL PROBLEMS AND STREET CHILDREN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Uyghur Identity and Culture: A Global Diaspora in a Time of Crisis” by Rebecca Clothey and Dilmurat Mahmut Amazon.com; “Uighur Folklore and Legends - 59 Tales and Children's Stories Collected from the Expanses of Central Asia” by Various Authors Amazon.com; “Uyghur Poems” by Aziz Isa Elkun Amazon.com; “Living Shrines of Uyghur China: Photographs by Lisa Ross” by by Lisa Ross and Alexandre Papas Amazon.com; Music: “Even in the Rain: Uyghur Music in Modern China” by Chuen-Fung Wong and Frederick Lau Amazon.com; “Uyghur Music/ Various” by Musiciens Traditionnels 2014 Amazon.com; “Female Voice of Uyghur Muqams & Folk Songs / Various by Traditional Amazon.com; About the Uyghurs and Their History: “The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land” by Gardner Bovingdon Amazon.com; “Soundscapes of Uyghur Islam” by Rachel Harris Amazon.com; “Language, Education and Uyghur Identity in Urban Xinjiang” by Joanne Smith Finley and Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “The Uyghur Language” by Gulis Aynur Derya Amazon.com; “A Brief Narrative of the Historical and Geographic Attributes of the Uyghur Identity: And Its Substantial Difference from the Turkic Identity and the Turkish Identity” by Mark Chuanhang Shan Amazon.com; “Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia” by Ildiko Beller-Hann, M. Cristina Cesàro, et al. Amazon.com; “The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History” by Rian Thum Amazon.com; “China and the Uyghurs” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com;

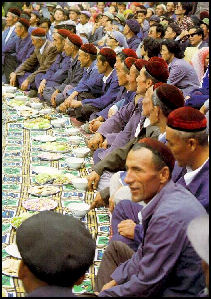

Meshrep and Dastans

In 2012, Bruce Hume of Ethnic ChinaLit wrote: ‘some 40 Uyghur singers of long rhymed tales that extol heroes in the Turkic tradition — known as "dastan" in Uyghur and Persian, "destans" in Turkish and "dasitan" in Chinese gathered recently in Hami, Xinjiang for an event that featured seminars and actual performances. According to the report re-published on the "China Ethnic Literature Network", some forty "dasitanqi" took part, with younger ones learning from masters who performed in the Hami tradition. [Source: Bruce Hume, Ethnic ChinaLit.com]

“Billed as a “training session,” this event is part of recent efforts by the authorities to document and preserve art forms of non-Han peoples in the PRC that have been categorized by UNESCO as an “intangible cultural heritage.” Considered a dying art, traditional dasitan are largely restricted to cities such as Hotan, Kashgar and Kezhou, as well as small towns in the Hami region of Xinjiang. But they are still frequently performed there in tea houses, bazaars and at "maja" — the burial sites of revered Muslims — and during the traditional Uyghur "Meshrep,"

Uyghur folk performance Meshrep has been proposed for UNESCO intangible cultural heritage status. According to a UNESCO description: A complete "Meshrep" event includes a rich collection of traditions and performance arts, such as music, dance, drama, folk arts, acrobatics, oral literature, foodways and games. Uygur "muqam" is the most comprehensive art form included in the event, integrating song, dance and entertainment. "Meshrep" functions both as a “court”, where the host mediates conflicts and ensures the preservation of moral standards, and as a “classroom”, where people can learn about their traditional customs. "Meshrep" is mainly transmitted and inherited by hosts who understand its customs and cultural connotations, by the virtuoso performers who participate, and by all the Uygur people who attend. [Ibid]

Uyghur Literature

The Uyghurs have a long history and their culture is very rich, unique and distinctive. Their oral literature and written literature are both very developed; their music, dance and crafts art are more famous throughout China. The culture and art of Uyghur people is unique and distinctive. The Story of Afantee, a music dance epic called The Twelve Mukam and local Uyghur dancing are very well known. Dances of the Uyghur people have a lot of categories; the traditional dances include Dingwan (dancing with several bowls on one's head), Dagu (dancing to the big drum beat), Tiehuan (dancing with iron rings), and Puta. Uyghur folk dances are further characterized as Sainaimu and Xiadiyana. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

Uyghur literature is very rich in style and subject matter. Many folk tales, parables, comedies, poems and proverbs praise the courage, wisdom and kindness of the ordinary people, while satirizing the greed, cruelty and foolishness of the exploiting classes. For instance, "The Tales of Afandi" contain stinging satire about the Bayis and Imams who bully the people.[Source: China.org china.org |]

Much of the written Uyghur literature has been passed down from the 11th century, such as the epic "Kutadolu Biliq" (Blessings and Wisdom) by Yusuf Hass Hajib, and The Turkic Dictionary by Mohamu Kashgar, which are important works for students of ancient Uyghur history, culture and language. More modern works include Maulabilalibin Maulayusuf's Wars on the Chinese Land, an epic describing the 1864 struggle of the Uyghurs in Ili against the Qing government. Mutalifu, the patriotic and revolutionary poet, composed poems such as "Chinese Guerrillas," "Militant Girls" and "Love and Hatred" during the Anti-Japanese War. After 19949, much work has been done to collect, compile and publish classic and folk Uyghur literature. |

Kutadgu Bilig

Kutadgu Bilig is a Karakhanid work from the 11th century written by the Turkic author Yusuf Khass Hajib of Balasagun. The title is variously translated as "The Wisdom which Brings Happiness", or "The Wisdom that Is Conducive to Royal Glory or Fortune", or "Wisdom Which Brings Good Fortune". The text reflects the author's and his society's beliefs, feelings, and practices with regard to quite a few topics, and depicts interesting facets of various aspects of life in the Karakhanid empire. The Kutadgu Bilig is widely read throughout Central Asia and the Islamic world. Uyghurs regard it as a great work of literature. Yusuf Khass Hajib is depicted on Kyrgyz currency. [Source: Ethnic China Lit, Bruce Humes, January 23, 2015, Wikipedia +]

Yusuf Khass Hajib is from the city of Balasaghun, the capital of the Karakhanid Empire in modern-day Kyrgyzstan. He died in Kashgar in 1085 and a mausoleum now stands on his gravesite. The Kutadgu Bilig was written in Uyghur-Karluk language (Middle Turkic), and employed the Arabic mutaqarib meter (couplets of two rhyming 11-syllable lines). +

The poem is “structured around the relations between four main characters, each representing an abstract principle” (Justice, Forture, Intellect and Man’s Last end). The author presented it to the Prince of Kashgar, and it does “appear to include instruction for how to be a good leader. In addition, the author of the Kutadgu Bilig states in the text that he was trying to make a Turkic version of something like the Shah-nameh.” The latter, also known as The Book of Kings, is considered the “national” epic poem of Greater Iran. +

Kutadgu Bilig Recited at Great Hall of the People

In January 2015, a new Chinese rendition of the Kutadgu Bilig was launched and an excerpt recited at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Former Minister of Culture Wang Meng — a Han who spent part of the Cultural Revolution in laboring among Uyghurs — and central government and Xinjiang dignitaries. The scholar Bruce Humes wrote: “The symbolism of this recital should not be underestimated. It took place on Tiananmen Square, the heart of political China, at a time when Xinjiang society is the object of a harsh crackdown that at times appears more “anti-Uyghur” than “anti-terrorist”. [Source: Ethnic China Lit, Bruce Humes, January 23, 2015]

In this context, the re-publication — it was first published in 2003, and nothing in the news item explains if there is any major difference between the two editions — of the Chinese-language Kutadgu Bilig is intriguing. Thus the questions: What is the nature of the work, and why the high-profile relaunch?

The highly publicized relaunch of this translation of Kutadgu Bilig appears to be aimed at: 1) Confirming and celebrating the historically heterogeneous nature of Chinese society; 2) Positioning ancient Uyghur classics as part and parcel of the “multi-ethnic Chinese” — or Zhonghuá — tradition; 3) Drawing parallels between the political philosophies of great thinkers such as Confucius and Yusuf Khass Hajib; 4) Highlighting trends in translation of the arts, i.e., that traditional uni-directional (Han-to-minority language) translation is now being replaced by a trend to pro-actively translatebetween the various languages of the People’s Republic of China; and 5) Reminding critics of the anti-terrorist crackdown that their target is separatists and terrorists, not Uyghur culture per se.

Uyghur dance

Traditional Uyghur Copper Ware

Reporting from Kashgar, Takahiro Suzuki wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “As I was walking along a road in a craftmaking area, I heard rhythmic sounds coming from a copperware store. I spotted a Uyghur craftsman with a serious look on his face hammering away as he formed a copper utensil.Copperware is a traditional Uyghur craftwork and its production center is Kashgar. The 40-year-old owner of the shop I entered said all of the products on display were made from scratch by hammering flat copper plates into shape. [Source: Takahiro Suzuki, Yomiuri Shimbun, August 5, 2014 ==]

“Various daily necessities such as pitchers, pots, plates and spoons were available in the shop. These products are made of three kinds of metal—brass, copper and cupronickel. Floral and other designs were etched on some of the items. A copper teacup I liked had a double-layered structure. As it was hollow between the layers, the cup could be held comfortably even when it contained hot water. The cup cost 60 yuan (about $9). The craftsman said he could make only four cups a day.” ==

Uyghur Knives

Reporting from the southern Xinjiang town of Yengisar, the center of traditional Uyghur knife-making, Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Here on the fertile edge of the Taklimakan Desert, people have long believed that placing a knife on their bedside keeps away bad dreams. On a baby's seventh day of life, it's tradition for parents to briefly slip a blade under the sleeping infant's head to guarantee a long and healthy life. By dusty roadsides, farmers with long white beards unsheathe their blades to slice open juicy green melons, selling sweet wedges for 15 cents. In open-air markets, butchers slaughter sheep, cattle and even camels in accordance with Muslim practice, skinning the hides and then swinging cleavers to parcel the carcasses into cuts of meat. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, September 17, 2014 ^=^]

“Over the centuries, Uyghur craftsmen have elevated knife-making to a high art, fashioning small folding qelemturachs and larger pichaqs one by one in scores of small factories and workshops across Xinjiang province. The most expensive and ornate boast silver blades and handles crisscrossed with intricate inlays of iridescent shell, stone, bone and other materials, often in geometric patterns with diamond, circle or even heart motifs. The craftsman's name and hometown are typically inscribed on the blade, in flowing Uyghur script and sometimes Chinese characters as well. ^=^

“One proprietor got lucky when a group of Russian motorcyclists and a busload of tourists who had driven all the way from Shanghai on China's eastern coast rolled up. Transporting knives back home would be no problem for them. "I didn't know anything about these knives until our guide told us," said Gennady Kopylov, 37, of Moscow, who bought a large kitchen knife for about $50. "I guess some Chinese might be scared now, you know, the Muslim thing, but these knives are great. And it's no problem to take them back on the bike." ^=^

“The Uyghur craft of knife-making is often passed from father to son. Down the road from Yengisar, at a dusty rest stop baking in the sun, one small knife stand was open, and outside, the owner's wife watched their toddler run around, naked except for a T-shirt. A drill, grinding equipment and other tools sat in a heap at the front door of the shop. No customers were browsing the exquisite wares, everything from plain $10 cleavers to a $500 silver blade with a decorative inlaid handle that takes one craftsman 15 days to produce. Asked whether he planned to pass the trade on to his boy, the young owner just sighed and said, "I have no idea." ^=^

Uyghur Knife Sector Hurt by Xinjiang Violence

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In the wake of a string of deadly clashes and terrorist attacks, including a mass slashing, that Chinese authorities have blamed on Uyghur separatists and religious extremists, the handcrafted knives have taken on a deadly cast. The violence has set back the once-thriving tourist trade to the south of Xinjiang province, and remaining visitors may think twice about the symbolism of giving anyone a Uyghur knife as a gift these days. For the few sightseers who still want them, confusion over restrictions on mailing knives or even taking them in check-in airline baggage has further damped the trade. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, September 17, 2014 ^=^]

“On a recent weekday, Yengisar, resembled nothing so much as a ghost town. Blade-shaped signs 30 feet tall stood forlornly above ample parking lots designed for tour buses, and colorful flags flapped in the wind, beckoning customers. Not only were there no shoppers, but no shops were open. The local workshops were shuttered as well. Finally, a policeman happened by and told the neighborhood mini-mart clerk he wanted to buy an animal-bone comb from the knife shop next door. The clerk called the owner, who hustled over to throw up his metal security door and make whatever sale he could.^=^

"Business is bad this year; there are no tourists," the salesman said as the officer picked out his comb and a few other shoppers wandered in, browsing the display cases stuffed with knives for every budget, from $5 pocket knives less than 2 inches long to kitchen cleavers and decorative silver blades with deer horn handles. Exactly why the entire strip of dozens of shops and small factories was shut down was unclear. One local said the craftsmen had simply gone off for 10 days to pick cotton in fields nearby; September is peak harvest season. ^=^

“But people here are skittish, and no one wants to share their name with a journalist. Another shop owner said proprietors had been ordered to close for a week — by exactly whom he didn't specify — because the provincial capital, Urumqi, a full 700 miles to the northeast, was hosting a high-profile international trade expo that week. Though the notion that authorities might extend security precautions such a distance may sound far-fetched, China has strict rules on weaponry. Firearms are tightly controlled and hard to obtain; all but the smallest knives are supposed to be registered with police upon purchase. ^=^

“China has periodically clamped down on knife sales around major national events. Ahead of the November 2012 ceremony at which Xi Jinping was elevated to the Communist Party's top post, for example, supermarkets across Beijing were ordered to stop sales of even small paring knives. Since then, a series of deadly attacks has set the nation on edge and given Uyghur knives an ominous taint, though it's unclear in many cases whether the assailants used Uyghur knives or mass-produced ones. ^=^

“Near the village of Kezile, a huge blue-and-yellow knife-shaped sign greeted motorists pulling in to refuel their vehicles and stuff themselves with lamb kebabs and noodles at the Brothers Fast Food halal restaurant. The knife shop next to the eatery was tightly locked up. Blue signs affixed to the front of the building warned: "Religious Activity in Public Spaces Is Strictly Prohibited." Another, smaller green sign detailed rewards up to $8,500 for tipsters who inform police about "terrorist activities." No one in the area seemed to know when the shop had shut, or when it might reopen. Six policemen sat under a canopy, keeping tabs.^=^

Uyghur Music and Dance

The Uyghurs are excellent at dancing. The "12 Mukams" (opera) is an epic comprising more than 340 classic songs and folk dances. After liberation, this musical treasure, which was on the verge of being lost, was collected, studied and recorded. The "Daolang Mukams," popular in Korla, Bachu (Maralwexi), Markit and Ruoqiang (Qarkilik), is another suite with distinct Uyghur flavor. [Source: China.org china.org |]

There is a wide variety of plucked, wind and percussion Uyghur musical instruments, including the dutar, strummed rawap and dap. The first two are instruments with a clear and crisp tone for solo and orchestral performances. The dap is a sheep skin tambourine with many small iron rings attached to the rim. It is used to accompany dancing. |

The Uyghur dances, such as the "Bowls-on-Head Dance," "Drum Dance," "Iron Ring Dance" and "Puta Dance," feature light, graceful and quick-swinging choreography movements. The "Sainaim Dance" is the most popular, while the "Duolang Dance," sometimes referred to as a flower of Uyghur folk culture, brims over with vitality. It depicts the hunting activities of the ancient people of Markit. The movements portray strength, wildness and enthusiasm. The "Nazilkum," popular in Turpan, Shanshan and Hami, fully reflects the Uyghurs' optimism and gift for humor. |

Twelve Mu Ka Mu

The Twelve Mu Ka Mu (Twelve Great Melodies) is the most famous Uyghur classical music. At harvest time, during great festivals or at Maixilaifu (the musical parties on wedding day), you will see people happily singing and dancing along with the melodies of Mu Ka Mu played by Dutaer, Rewapu, Tanboer, Aijieke, Kalong, tambourine and other musical instruments played by the Uyghurs. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

The Twelve Mu Ka Mu has a long history. Its early forms were was spread orally. In the 16th century, Twelve Mu Ka Mu in their present form began to take shape as music, poetry and literature, incorporating not only classical melodies, but also folk-dance music and narration songs. The whole Twelve Mu Ka Mu includes more than 170 qu names and 72 melodies, and varies to some degree from region to region in Xinjiang. According to different regions, the Mu Ka Mu (great melody) is also divided into five types: "Kashi Mu Ka Mu", "Daolang Mu Ka Mu", "Turfan Mu Ka Mu", "Hami Mu Ka Mu" and "Yili Mu Ka Mu". Among them, the "Kashi Mukamu" is in the longest. In its complete form, with its abundant melodies, it takes more than 20 hours to sing from the beginning to the end. ~

The whole body of music is divided into 12 great sets, the Mu Ka Mu. Each Mu Ka Mu has different tone characteristics, and is divided into three parts: Qiongnai'eman, Dasitan and Maixilaifu. 1) "Qiongnai'eman", meaning "great melody", begins with a scattered array orderly songs with deep emotion. "Taizi" closely follows it. Progressing through the "Nusihe", "Saileke" and "Kala" segments, it reaches a climax with the exciting and warm "Sainaimu" and "Dasanleke", and comes to the end with the lively "Taikate". 2) The "Dasitan" is made up of three to five narration songs with different meters and speed, with folk music parts inserted among it. At the beginning it is a little slow, but gradually picks up speed as it goes, ending with an exciting and joyful climax. 3) The "Maixilaipu" is made up of three to seven singing and dancing parts with different meters. It is vigorous and powerful, with no intermezzo, and keeps a warm mood from the beginning to the end. ~

As the Twelve Mu Ka Mu were passed down from generation to generation orally, knowledge about the music declines as the world modernized as Uyghurs became interested in other things. By the 1950s only two to three elderly performers could sing it completely. After the takeover of China by the Communists, the central government organized manpower and resources to save the art form. Famous performers in the southern and northern parts of Xinjiang were invited to share their knowledge and expertise. Tu'rdi Ahung, Rouzi Tanboer and others collected, recorded and organized the Twelve Mu Ka Mu and formally published it in 1960. After that parts of the Twelve Mu Ka Mu were broadcast on radio and television and performances of Mu Ka Mu were organized for the stage. ~

Uyghur Hip-hop

Chris Walker and Morgan Hartley wrote in The Atlantic, “Many Uyghurs feel they have become strangers in their own land; for instance, in Urumqi, the region’s sprawling capital, Uyghurs now represent just 12 percent of the city’s population. But in the city’s poorest districts, some Uyghur youth have turned to a non-traditional outlet for maintaining cultural pride: hip-hop. Since 2006, this home-grown rap and dance scene has drawn together thousands of Uyghur fans across Xinjiang, and has even managed a feat the founders didn’t expect to achieve: attracting Han Chinese fans. [Source: Chris Walker and Morgan Hartley, The Atlantic, October 29, 2013]

“Ekrem, aka Zanjir, was the first Uyghur rapper and a co-founder of Six City, Urumqi’s most popular rap collective, for which he now serves as producer and business manager. It’s a part-time gig. In his spare time, he moonlights as a software developer, while other members of the collective drive hospital shuttles or work in traditional Uyghur dance shows to make ends meet.

“It’s easy to see why Six City’s young rappers feel marginalized. They hail from Tianshan, a neighborhood on Urumqi’s southern edge, away from the elevated freeways and skyscrapers that have transformed the city over the last 15 years. The buildings in Tianshan are squat and gray, and feature the Uyghur language’s Arabic script on storefronts. One resident, an interpreter, described the neighborhood as “Urumqi’s Harlem.”

“In a simple basement studio wedged between tire stores in a Tianshan strip mall, Ekrem and three other Six City MCs crammed around a computer and a single microphone. On a shelf was a stack of records from their idols—American hip-hop stars like Snoop, Eminem, Ice Cube, and 50 Cent. The men would have fit comfortably in urban America: Ekrem wore a black Dodgers cap, while Behtiyar, a fellow member, had slick-backed hair and wings tattooed on his forearms. Eager to show off, one rapper called “MC-5" started to freestyle.

“He was good. Rap in Uyghur is fluid and quick, and the vowels come in rapid succession, from the back of the mouth, producing a smooth sound. “Uyghur is much better for rap than Mandarin,” Behtiyar explained. “Uyghur is phonetic, like English, so it’s easy to make dope rhymes.” By contrast, he said, it is more difficult to sing in Mandarin. Six City has other reasons to rap in Uyghur—it’s part of their heritage. Because it’s difficult to get a job with a degree from a Uyghur school, more Uyghurs are studying in Chinese. “It’s important to protect our language. Sometimes I see these Uyghur kids out in the street speaking Chinese to each other,” Ekram said, shaking his head. He added that there are only ten really good Uyghur rappers. “Most Uyghurs rap in Chinese. They go study Chinese in school, and they just can’t find the right words in Uyghur.”

Chinese Government Pressure on Uyghur Hip-Hop Artists

Chris Walker and Morgan Hartley wrote in The Atlantic, “The collective has had to adapt to government pressure...“There’s a lot of lyrics we can’t express, so we have to be smart” Behtiyar said. Six City steers clear of politics and discrimination, and instead focuses their songs on Uyghur pride or problems of drug and gambling addictions in Urumqi’s low-income neighborhoods. It’s an important way to raise awareness about the culture, and “show China that we’re not a bunch of primitives” says Ekrem, referring to a frequent Han stereotype of Uyghurs. [Source: Chris Walker and Morgan Hartley, The Atlantic, October 29, 2013]

“Still, Six City struggles when hit with events outside their control, such as the ethnic riots that shook Urumqi in July 2009. Following the turmoil, which pitted the city’s Han and Uyghur populations against each other, Urumqi’s hip-hop scene shut down for a year. Groups like Six City couldn’t hold concerts because of a ban on public gatherings, or spread new music online because of severe Internet restrictions. The collective decided it was too dangerous to hold their famous underground house parties, and didn’t perform together again until 2011.

“Even today, in a calmer Urumqi, Ekrem treads lightly. The producer will not release MC5's upcoming album officially because all the lyrics are in Uyghur. To avoid censorship, Ekrem plans to print the album on blank CDs and sell copies for 5 RMB (about 80 U.S. cents) in the capital’s bars and streets.”

Uyghur Hip-Hop and Its Han Chinese Fans

Chris Walker and Morgan Hartley wrote in The Atlantic, “But even Six City writes half of their lyrics in Chinese. Their reasoning for this is purely pragmatic. According to Ekrem, it makes Six City’s music more accessible to the mass market of Mandarin speakers. “And the Chinese Government censors less when you mix in Chinese lyrics” he said, with a smile. [Source: Chris Walker and Morgan Hartley, The Atlantic, October 29, 2013]

“The two albums Six City have released have helped broaden their exposure and attract attention from Han Chinese fans. In September 2013, Six City was invited to Beijing to perform their second concert in the capital in the past two years. On a packed floor at the Mako Live House, the mostly-Han crowd eyed Six City’s MCs, who were dressed in bright jumpsuits and baseball caps, with curiosity. Though some of the collective’s music videos have achieved popularity on Youku (China’s YouTube), they still remain unfamiliar to most audiences. Some thought that they were from a foreign country.

“Yo Yo Yo” Murkat, the lead rapper, shouted, waving his arm up and down like Eminem. A thick plume of smoke shot up from the front of the stage. Lights flashed. The beat dropped. And the group launched their most popular song, “Cuyla.” “Praise, Praise, Praise your land! Praise your homeland!” they sang in Uyghur. The crowd danced and cheered wildly. The music sounded fresh. Many started waving their arms—mimicking the Uyghur performers.

“Word about Six City seems to be spreading. Later on in the trip, in the southern Chinese metropolis of Guangzhou, Ekrem was surprised to find himself somewhat of a celebrity. As he was walking through the airport to catch a flight back to Urumqi, a Han fan rushed up to him. “Hey! Was that you rapping at the concert in Beijing?” “Yeah.”

Uyghur Boxer and the Olympics

One of China's Olympic boxers, Mehmet Tursun Chong, is an Uyghur grew up on a farm in Yizebah, a village in southwestern Xinjiang with views of the Karakoram Mountains and the Hindu Kush in northern Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Mehmet Tursun's family said he was so keen on boxing when he was a little boy that one day he filled a sack with sand and attached a rope to it. But he could not reach the branches of the apricot trees to hang it up, so his uncle did it for him.

Now is regarded as one of the best boxers in China. His training regime is ferocious. In the past it has included running at altitude in Kazakhstan and climbing a mountain carrying iron weights. His normal diet of mutton and high-fat Uyghur lamb was replaced by his coach with a high protein diet, including a lot of seafood. Before the Olympics he trained in Urumqi in front of a banner that read “Above All Else, the Motherland.” [Source: Hugh Sykes, BBC News, July 29, 2008]

Image Sources: Uyghur image website; All Empires com; Silk Road Foundation; Mongabey; CNTO; Guicida Birmezir

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2015