UYGHUR SOCIETY

Uyghur society has traditionally been divided into three classes: 1) the intellectuals; 2) the traders; and 3) the peasants. Each has its own relationship with the Chinese. The traders have tended to be pragmatic because the are reliant on Chinese good will. The peasants have tended to be passive because they cherish government hand outs. The intellectuals have traditionally been rebels who were most vehement and outspoken in their opposition to Chinese control.

Society had traditionally been organized along patrilineal lines with deference and respect paid in accordance with age and rank. Certain relatives are addressed with particular terms of respect and endearment. Old siblings are distinguished from younger ones with special words. Inheritances has traditionally been divided among sons.

Tribal and clan association have traditionally not been as important in Uyghur society as they have been in other Central Asian and Islamic societies. Justice has traditionally been meted out through Islamic law (sharia) and adat (customary practice). Uyghurs prefer to have legal matters settled in their justice system rather than in Chinese courts.

The Uyghurs employed a naming system in which father's and son's names are linked. This system has traditionally appeared at the transition period from matrilineal clan system to patrilineal clan system.

See Separate Articles: UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com ; UYGHUR CULTURE. LITERATURE, KNIVES AND HIP HOP factsanddetails.com ; UYGHURS, CHINESE AND ECONOMICS factsanddetails.com ; UYGHUR SOCIAL PROBLEMS AND STREET CHILDREN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Kashgar: Oasis City on China's Old Silk Road” by George Michell, Marika Vicziany, et al. Amazon.com ; “The Uyghurs: Kashgar before the Catastrophe (English and Uighur Edition) by Kevin Bubriski, Tahir Hamut Izgil, et al. Amazon.com; “Under the Mulberry Tree: A Contemporary Uyghur Anthology” by Munawwar Abdulla, Sonya Imin, Maidina Kadeer, Emily Zinkin Amazon.com; “Uyghur Stories - Real-life scenes from Xinjiang” by Ingrid Widiarto, Ann Dechesne-Huntley, et al. Amazon.com; “Down a Narrow Road: Identity and Masculinity in a Uyghur Community in Xinjiang China” (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Jay Dautcher Amazon.com; Food: “Silk Road Recipes: Parida's Uyghur Cookbook” by Gulmira Propper , Welles Propper, et al. Amazon.com; About the Uyghurs and Their History: “The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land” by Gardner Bovingdon Amazon.com; “Soundscapes of Uyghur Islam” by Rachel Harris Amazon.com; “Language, Education and Uyghur Identity in Urban Xinjiang” by Joanne Smith Finley and Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “The Uyghur Language” by Gulis Aynur Derya Amazon.com; “A Brief Narrative of the Historical and Geographic Attributes of the Uyghur Identity: And Its Substantial Difference from the Turkic Identity and the Turkish Identity” by Mark Chuanhang Shan Amazon.com; “Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia” by Ildiko Beller-Hann, M. Cristina Cesàro, et al. Amazon.com; “The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History” by Rian Thum Amazon.com; “China and the Uyghurs” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com

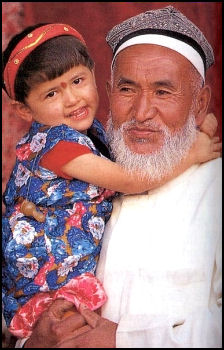

Uyghur Life, Character and Appearance

Uyghur people depend upon agriculture. They plant various crops such as cotton, grain, corn, and rice. Many are also good at gardening. The largest grape production area in China is situated in the Turpan Basin, located 184 kilometers from Urumqi, the capital city of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

Uyghur men sit around and drink tea. It is not unusual for a old man to pull out a long-necked, stringed rawap and strike up a tune. Especially in rural areas men and women tend to socialize separately. A “mashrap” is a traditional all-male gathering where participants play music, recite poetry and socialize. Uyghur men have traditionally been kind of macho in a Middle Eastern way. Many carry knives. Connected eye brows is regarded as a mark of beauty among Uyghur women.

The appearance of individual Uyghur varies widely. Some are dark and Middle Eastern looking. Other look like Europeans. Some look so much like Europeans in fact they have played Europeans in Chinese-made movies.

Uyghurs come across as being rougher and tougher than Chinese. Peter Hessler wrote in the New Yorker: “Their body language was eloquent...they swaggered. They had a reputation for carrying knives.” They “had a hard gaze, and they carried themselves with an intensity that made the Chinese nervous.” Hessler once observed a group of drunk Uyghurs amuse themselves by burning holes in their forearms with cigarettes.

Uyghurs treat their women with respect and exhibit behaviors that seem more Westernized than Chinese. Hessler wrote: “They were great hand shakers — a rarity in China. If a woman came to Uyghur table, the men stood up.” However, many find that Uyghurs are worse than Chinese about waiting in line.

A meshrep is a traditional Uyghur gathering.

Uyghur Marriage and Wedding Customs

Before Communism, polygamy was allowed but rarely practiced. Monogamy was the norm. Unlike some Turkic groups which discourage marriages to close kin, Uyghur have traditionally married partners in their village or neighborhood who are often closely related. Matchmakers have traditionally worked out of local bazaars.Traditional weddings feature singing, dancing and feasting. After the wedding women take home gifts of flatbread. After marriage, the couple has traditionally moved in with the groom’s parents, with the couple living a separate unit in the family courtyard house.

According to Chinatravel.com: “Uyghurs are monogamists. The tiqin, marriage interview, and marriage contract ceremonies are held before marriage as a show of respect and prudence towards marriage. A marriage interview is a necessary step that must be taken if a young man falls in love with and wishes to be married, or a family wants to arrange a marriage for its son. Before a marriage-interview, the prospective bridegroom must make sure that he knows his love's background, including her age, appearance, character and family members. He will propose the marriage when he feels it is appropriate. In many cases the man and the lady might have previously been in courtship. They would first agree to marry with each other and then ask the family members of the male to conduct a marriage-interview so as to publicize and make their relationship legitimate.” [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

The bride is expected to be virgin. In the past girls married before 16 years of age. After this age they were considered old maid. Now they marry usually after 18 in the rural areas and later in the cities. Polygamy was practiced at one time but no longer is as Chinese marriage law only recognizes one husband one wife families. After the wedding the bride has traditionally lived with the bridegroom family.[Source: Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *]

Marriages have traditionally been arranged by parents, though especially in the cities the desires of young men and women are respected. Usually the groom’s family asks a go between to arrange the marriage of their son. The go between visits the bride’s family, bringing some gifts. If they accept the gifts, it means the wedding is likely to go forward. After this visit the bride’s family tries to learn as much as possible about the groom and his family, asking friends and relatives about him. If they think they can accept him there is a second meeting when they try to agree about the conditions of their future life such as where they will live and how often they will visit her parents. They also discuss also the economic conditions of the marriage, and detail the gifts they will provide. In the third meeting they fix the date of the ceremony.

On day of the wedding, the groom goes with a music group to fetch the bride. She waits veiled and dressed a traditional red color dress, though in some places white is now favored As part of the wedding day activities, the bride’s party blocks the way to her house. The groom party must open the door giving gifts and singing. Once they get their hands on the bride they carry her to the groom's house. There, the oldest woman in the family blesses the newlyweds and lifts the veil of the bride, allowing the groom to see and kiss the bride. Then there is a party, where young people party with their friends, often drinking and dancing until late in the night. In days that follow week there will be many banquets offered by the two parties to the friends and relatives.

Uyghur Towns and Homes

Uyghurs have traditionally lived in towns set up around oases. At the center of a typical Uyghur town is bazaar and mosque. Around it are tightly backed houses, and narrow alleys. Water flows through canals along the main streets and nourishes trees and garden plots with melons and vegetables.

Traditionally, Uyghurs have lived in mud brick houses. Some were built around a Uzbek-style courtyard houses. Families gather in the courtyards, where grapes are often grown and special airing houses for grapes are set up. Today many Uyghurs live in concrete houses and apartments.

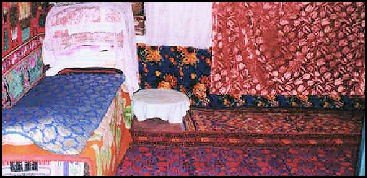

Residential buildings of the Uyghur people are characterized by courtyard clusters. Their entrance doors usually face the west. The Architecture is square with deep, front corridors The layout of a hall is modest; the walls are white and blue decorated with hanging tapestries; the bed is placed close to the wall and the beddings are under a carpet with a pair of pillows on it. Normally in the middle of a room there is a long or round table; the furniture is usually adorned with an embroidered; folk pictures are placed on the ground. Uyghur people like to grow various plants, flowers, fruit trees, and grapes. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

Uyghurs sleep on beds which are essentially 10-by-12 foot earthen slabs or brightly draped wooden platforms. Near the kitchen mutton hangs from hooks in the house. In Xinjiang, where many people still can not afford refrigerators, ice boxes are still used. The ice for the ice boxes is stored during the summer in caves behind thick wooden doors insulated with felt and transported to customers on a carts lined with felt.

Uyghur Urban Housing

In Kashgar and other urban areas many Uyghurs live in mud-brick courtyard homes on narrow winding streets in old towns. Ecologically efficient, the homes are cool in the summer and warm in the winter. Many mud-brick homes were originally bought with gold coins and have been passed down through the generations. In the Old City of Kashgar, homes are adjacent and interconnected. Most have two stories high and arranged around central courtyards. They look drab and crude on the outside. On the inside they often have white-washed plaster walls and painted ceilings, further enhanced with colors by carpets and paintings.

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, “In Uyghur style, the home has few furnishings. Tapestries hang from the walls, and carpets cover the floors and raised areas used for sleeping and entertaining. The winter room has a pot-bellied coal stove; the garage has been converted into a shop from which the family sells sweets and trinkets. Nine rooms downstairs, and seven up, the home has sprawled over the centuries into a mansion by Kashgar standards.” The owner of the house said, “My family built this house 500 years ago...It was made of mud. It’s been improved over the years, but there has been no change to the rooms. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, May 28, 2009]

Large-scale, raw-earth building complexes, like those in Kashgar’s Old Town, are rare, according to Wu Dianting, a professor of regional planning at Beijing Normal University's School of Geography, who did field research in Kashgar in 2008, told the Washington Post. “The buildings are very scientific. They are warm in winter and cold in summer. The technology used saves material and is environmentally protective,” Wu said. [Source: Maureen Fan, Washington Post, March 24, 2009]

The old town is also one of the few authentic representations of Uyghur culture left, he said. “The old town also reflects the Muslim culture of the Uyghurs very well — it has the original taste and flavor without any changes. Here, Uyghur culture is attached to those raw earth buildings. If they are torn down, the affiliated culture will be destroyed.”

The Old City in Kashgar is being torn down under orders of the Chinese government and Uyghurs are being forced to move into cinder block apartments on the outskirts of the city. See Separate Artilce on the Tearing Down of Kashgar.

Uyghur Urban Life

Inside an Uyghur house Henryk Szadziewski wrote on Opendemocracy.net, “In the heart of Kashgar's old city, the bustle of central Asian life has not changed in centuries. In bright sunlight, the mud-brick buildings seemingly blend in with labyrinth-like streets powdered by the sands of the Taklamakan desert. Coppersmiths hammer away making shapely bowls, pans and jugs, which will sit on the shelves of cool courtyard-fronted homes. A seller of shirniliq meghiz (hand-made Uyghur candy) pushes his cart in the heat of the day, stops, and wipes the sweat from his brow. Women, their heads covered with brown-colored gauzed blankets, move from market-stall to market-stall discussing the cost of spices (sold in huge sacks) and cuts of mutton (hanging on shaded meat-hooks). Vendors selling hand-sewn doppas (Uyghur skull-caps) and brightly decorated knives from Yengisar, (the best in the region) watch donkey-cart drivers shouting the warning posh! posh! as they navigate the streets and the people. Minarets subtly overlook over the scene, reminding Kashgaris that in addition to trade, Islam is also an influence on their daily routines. Then, a muezzin's call breaks the activity and stirs the pious to hurry along the narrow streets to attend prayers.” [Source:Henryk Szadziewski, Opendemocracy.net, April 03, 2009]

‘such a portrait of timeless Uyghur traditions and livelihoods - so familiar from the work of travel-writers and journalists - is compelling. But there is another Kashgar, one firmly rooted in the 21st century. This Kashgar contains high-rise apartment blocks, cellphones, cars, western fashions, Dove chocolate bars and mass-produced consumer goods. Kashgaris are not only coppersmiths and traders; the Uyghur men and women of this city are also bank-tellers, university professors and auto-mechanics.”

Tearing Down the Old City of Kashar, See Separate Article

Uyghur Food and Drink

Uyghurs eat three meals a day. They like to eat pancakes, melon or guard jam, sweet jam, milk tea, and oil tea for breakfast, various staple foods for lunch, and pancakes, steamed dumplings, and noodles for dinner. Uyghur people enjoy strong tea and milk tea. In summer different fruit and melons are consumed. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

Uyghurs eat mutton, circular Central Asian bread and Uyghur goat-head soup. A meal must have meat — usually mutton to be considered a proper meal. Many Uyghur drink heavily put they don’t touch pork. Before the Chinese began arriving in Xinjiang large numbers and most of the dinning cars on the trains to the region were mostly empty because many of the dishes they served contained pork.

In the past, many Uyghur farmers lived on a diet of narrow-leaved oleaster and dried apricot and peach, mulberry and grain porridge. Now, wheat flour, rice and maize are the staple foods. Uyghurs in some areas like milk tea with baked maize or wheat cakes. Some are made by mixing flour with sugar, eggs, butter or meat and are delicious. Paluo (sweet rice or grabbed rice, see below)—cooked with mutton, sheep fat, carrots, raisins, onions and rice, is an important festival— food for guests. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Roasted meats and kebabs are popular local delicacies in Xinjiang. There are a great variety of roast meats and kebabs made from things like chopped entrails, whole lamb, and meat baked in a tonnir (see below). If you do not taste roast mutton while you are in Xinjiang, it would be a great pity. Kashgar mutton is unique in that sheep are fed with grass grow on land rich in alkaline. So mutton here is more delicious. [Source: Uyghur Freedom Foundation]

Uyghur eat tasty but high-fat Uyghur lamb and 20 different varieties of raisin roasted mutton, drink snow lilly tea from the Tian Shin mountains and consider horsemeat sausages a winter food because they heat up the body they say.

Common dishes eaten in Xinjiang include jiaozi (stuffed pancakes), lamb kebabs, nang (flat loaves of bread), spicy Xinjiang chicken, lamb, cucumbers with red peppers, mushrooms and white fungus, zhang cha yazi (excellent chili duck smoked in jasmine tea, rubbed with rice wine, and air dried), mutton, eggplant, mixed vegetables, steamed bread and rice, lamb and beef dishes, pilaf and stew made with sheep organs and intestines casings stuffed with rice. Sheep lung soup and shirniliq meghiz (hand-made Uyghur candy) are popular.

A feast offered by villagers includes mutton soup, delicious cold chicken, fresh apricots, water melon and flat round Uyghur bread. Uyghur meals have traditionally eaten on the floor or a raised platform off a dasturkhan, a tablecloth covered with fruits, sweets, nuts and bread. Describing an Uyghur restaurant near Kashgar Allen wrote: "There were no tables and chairs. We sat cross legged on the broad-covered spring of an old brass bedstead., and imitation of the kang. We dined on strong tea and hand-pulled noodles mixed with bits of lamb and vegetables."

Uyghur Grabbed Rice

Grabbed rice—known in the Uyghur language as "poluo"—is one of the favorite foods of the Uyghur people. Rice is mixed and fried with mutton, onions, carrots, raisins and vegetable oil. At the festivals, during special occasions days and on wedding days or funeral days, Uyghur people entertain relatives, guests and friends by cooking up great pots of grabbed rice. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

According to the tradition, when having meal, the host spreads a clean tablecloth on the kang, table or carpet, and people sit around the tablecloth. Then, the host carries in a basin with one hand, and a pot with the other hand. The guests wash their hands one by one, after which the host gives them a clean towel to dry their hands. Then, the host or hostess places a tray with grabbed rice on it in the middle of the tablecloth, and asks the guests to directly grab the rice from the tray and eat it. Guests who are not accustomed to grabbing with hands can use small spoons to eat.

There is a great variety of Uyghur grabbed rice based on its ingredients. First there is the oil it is cooked in: vegetable oil (huma oil, rapeseed oil, melon seed oil and cottonseed oil), butter, mutton oil, marrow oil or safflower oil. It is said that grabbed rice cooked in marrow oil is most nutritious. Instead of mutton, some people use chicken, duck meat, goose meat, beef or the meat of a snow cock or pheasant, with grabbed rice made with snow cock meat, a kind of rare delicacy. Instead of raisins or in addition to them some people use sun-dried apricots, preserved peaches, bean noodles, cabbage, tomato or hot pepper, in what is called sweet grabbed rice or vegetable grabbed rice. ~

Some people also pour some sour milk on the grabbed rice. This, it is said, improves appetite and digestion, and relieves summer heat. There is also a egg grabbed rice. To make this the chef digs a small nest the size of an egg in the rice, and then beat an egg inside it. When the grabbed rice becomes is ready, the egg is fully glued with rice, and the sweet oil smell reaches the nostrils when people eat the rice. "Aximantu" is a steamed stuffed bun with a thin skin made of grabbed rice. Thin-skin steamed mutton buns are also tasty. They are often served to honored guests. ~

Nang: Roasted Uyghur Flat Bread

When you come to the Kashgar area, whether it is in the city, countryside, a street or an alley; during a jubilation-filled wedding banquet, or in a camel team, you can find and taste nang: a kind of round roasted bread,, the traditional Uyghur staple food. Nang is everyday food for Uyghurs, important as steamed dumplings and buns to the northern Chinese and rice to the southern Chinese. The word Nang comes from Persian. Uyghurs originally called it “Aimaik”. After Islam was spread to Xinjiang the name was changed for “nang”. Generally, nang is made with wheat flour but it can also be made with maize flour. [Source: Uyghur Freedom Foundation]

Nangs are baked in a stove called tonnir that has a big stomach and a little mouth and is made from sun-dried earth bricks. To make nang first heat the tonnir with firewood or charcoal. When the flame is extinguished, slightly-leavened nang dough is placed on the inside walls of the tonnir. About 20 minutes later the nang is ready to eat. Small amounts of salty water and leavening are added to flour to make the dough, which is kneaded evenly and rolled. Hot Nang is crisp and tasty. Uyghur often eat it with tea and mutton kebabs or roast mutton. In autumn, when grapes are ripe, they eat it with grapes, which are said to be more tasty and nutritious. Nang is made with only a little water in it so it doesn’t get go moldy easily and is easy to preserve. In the harvest seasons, farmers usually carry several dozen nangs with them. The same is true with people traveling or working in the Gobi desert. A few minutes after nang is buried under the hot sand, it becomes crisp and delicious.

Generally, the tonnir is constructed of sheep hair and clay. It is about one meter high. The stomach is big and the mouth is small. The shape is like an inverted water vat. Near the tonnir is a square stand is built by of sun-dried mud brick. Before making nang, coal is burned under the tonnir. When the bright flame disappears, the wall of tonnir is hot enough to make nang. Nang contains relatively small amounts of water, so it can be stored for a long time and carried when traveling. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

Nang is believed to have a history of more than 2,000 years in Xinjiang. In the Chinese historical records it was called "Hu nang" and "stove nang". A 1,000-year-old nang evacuated by archeologist did not have any mold on it. It is said that when the Chinese monk and Silk Road explorer Xuanzang went through Gobi desert he had nangs with him to fend off hunger. According to historical records, as early as Han and Wei Dynasties, nangs were sold in the markets of Chang’an (ancient Xian). It is also said that, after “the revolt of An Lushan of Shi Siming”, the Tang Dynasty ruler Xuanzong ate nang bought by the brother of Yang Guifei.

Watching a Uyghur baker in Kashgar, Allen wrote: "He formed dough into round shapes and sprinkled sesame seeds and water on them. Then his upper half disappeared as he dipped into the oven to slap the circles of dough onto the inside wall. In minutes he dipped into the oven again and removed...bagels! At lest that was what they looked and tasted like. Uyghur call them girde nan, round bread.”

Types of Nang

At present there are approximately 50 kinds of nang, including with meat, nang with oil, and nang with sesame. Different nangs are for different occasions. Big nangs such as "Aimaike" and "Shearman" are mainly for holidays and joyous occasions. Small portable nangs such as "Tuachi" and "Katili" are carried by travelers and eaten at work. Most nangs are baked with wheat-flour, corn or rice flour. Their names are derived from their ingredients, shapes and roasting methods. Nang with lamb oil in it is called oil nang. Nangs with ziyadan (seeds of a kind of grass), mutton cubes and spices such as pepper and onion fillings are meat nang. Nangs with sesames and grape are called sesame nang. [Source: Uyghur Freedom Foundation]

All the nangs are round, but the shapes and sizes are different. The middle part of "aimanke" nang—the so-called the king of nangs—is thin, and the edge is thick. The central part is printed with patterns and the diameter is about half a meter. About two or three kilograms of flour is needed to make one. The smallest type of nang, called "zhaluoxi", is several centimeters thick and has a diameter of about 10 centimeters, with dip in the middle part. This kind of nang is associated with the Kashgar (Kashi) region. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

"Xikeman" nang means sweet nang. It is coated with a layer of crystal sugar water. When it is ready, its surface glitters brightly and transparently, and it is sweet and delicious. Meat mutton nang is made by adding crisp mutton, ziran powder, pepper powder and onion dust to the flour. Oil nang is made with unleavened dough rolled in vegetable oil or mutton fat. The skin is very thin. Because of its savory and crisp characteristics, it is often used to entertain guests on the festivals of jubilation. ~

Uyghur Eating Customs and Taboos

According to Chinatravel.com: Uyghur people never eat pork or the meat of other animals which are not killed by people or without blood-shedding. When guests come, the host should invite them to take the senior seats, treat them first with tea or milk, and then bring some pancakes, cookies and candy. Fruits or vegetables should also be provided in summer. When the meal is ready, the host will bring a kettle of water to invite the guests to their wash hands and then treat them with Zhuafan (rice taken by hands).When the meal is finished, the elder people will take the lead to conduct Duwa, a kind of local pray rite. Guests should stay in their seats until the host clear up all the used utensils and dishware. It is not polite for the guest to fiddle with the food on his dish, to go close to the boiler, or leave some food in his bowl. If rice falls out of the bowl the guest must pick it up and put it on their tissue. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

Rice cannot be put back once taken. After the meal, guests should not stand up or behave carelessly when the elder people are holding the Duwa rite. At dinner time, all family members should first wash their hands and sit together with the seniors in front of the salt. It is very discourteous if somebody splashes the water on their hands. Never place the Nang (a local food like pancake) upside down while eating it. It is impolite to wear a small shirt or a cloth with a large collar. Normally the frock should extend to ones knee and the trouser should reach the foot-surface. Pants should never be worn on the outside. \=/

Uyghur people never make their entrance door face west. When they sleep, they usually lie on their back with their head towards the east. When male friends meet with each other, they should shake hands, solute, touch their chest with two hands, and withdraw one step with their right arm on the left side. Females should solute after meeting each other and then say goodbye. Two hands should be used when receiving gifts or treated with tea. \=/

Uyghur Drugs and Smoking

Uyghur areas are famous for hashish. Hashish — often simply called hash — is produced from resin and trichomes taken from of female cannabis sativa and cannabis indica plants, and compressed into bricks. The drug has been smoked for more than a thousand years in the Middle East, where, in some regions, it is still popular among Muslims who are not allowed to drink alcohol. It is more popular in Europe than in the United States and is smoked there mixed with tobacco in hand-rolled cigarettes with a cardboard filter. .

Hashish generally has a THC content of 7 to 20 percent. Some high quality hashish has a THC content of 28 percent. In Europe in recent years it has become common for hashish to be adulterated with various kinds of impurities such as Vaseline, beeswax or tree resin. .

Charas — which is sometimes referred to as hashish — is made by hand rubbing resin directly from the cannabis plant. It is produced primarily in India and Nepal. Hash oil is made by boiling the cannabis plant in alcohol, filtering out the solids and evaporating out the water. Hash oils have a THC content of 20 to 45 percent. Some extremely potent versions are 78 percent THC.

Hashish comes in variety of colors: black, dark green, red or golden color. Most hashish has some plant material and color of the hashish often indicates what this plant material: low-quality green from leaves and trippier gold or red from gold or red flowers and trichomes.

Hashish also varies in hardness and in texture from hard and bricklike, to soft and pliable to gooey High quality hashish is nearly 100 percent resin and is usually black and soft and can be easily molded with the fingers. All hashish can be softened by applying heat. Poor quality stuff is hard and brittle and has to be heated for some length of time to make pliable enough to easily break off.

Hashish is valued at about $4 million per ton. It is more compact than marijuana and ths preferable from a smuggler’s point a view. See Hashish

Uyghur Clothes and Headgear

The Uyghurs' cotton growing and cotton yarn spinning industry has a long history. Working people usually wear cotton cloth garments. Men sport a long cotton coat or gown called a qiapan, which opens on the right and has a slanted collar. It is buttonless and is bound by a long square cloth band around the waist. Women wear broad-sleeved dresses and black waist coats with buttons sewn on the front. Some now like to wear Western-style suits and skirts.

Uyghurs, old and young, men and women, like to wear a small cap with four pointed corners, embroidered with black and white or colored silk threads in traditional Uyghur designs. A qiapan has a stiff collar, no buttons, and a lower hem extending to the knee. There are dozens of embroidery styles. Popular motifs include vines, pomegranates, moons, arabesques and abstract geometric patterns.

Men have traditionally worn long tunic coats with stripes or plain colors, leather boots and a four-sided a pillbox-type hat, called a dorha, or a skullcap. Long trousers are worn with slippers or are tucked into boots. Sometimes a triangular folded scarf is wrapped around the waist. Many old Uyghurs have long beards and wear a tall black cotton hat with fringe of fur at the bottom.

Uyghur extensively use embroidery to decorate their clothes and hats. Silk thread flat embroidery, shizi color embroidery, silk thread knot embroidery, bead-string patch embroidery, grid supported embroidery, gold surrounded silk-thread embroidery, floss embroidery, and combined embroidery made through procedures of puncture, prick, bunch and set. Uyghur females embroider color and various pictures on the four surface parts of a cap, and knit them together. They then put an inner layer into it and set a black floss rim to seal the cap. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

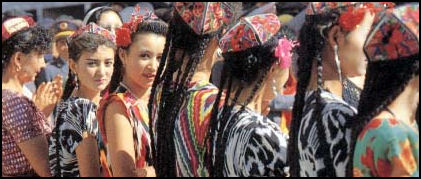

Uyghur Women's Clothes, Hats and Hairstyles

Uyghur women wear a loose-style, long-sleeve tunic dress and a sleeveless waist coat and brightly colored scarves. Many wear tie-dyed silk garments with colorful patterns that date back thousands of years. These satin-weave garments are so valuable that they often make up large part of a Uyghur woman's dowry. Colorful head scarves are popular with women. In Kashgar women not only cover their heads but also veil their faces with brown gauze. Married Uyghurs women in Kashgar often wear a brown paranja veil. Some wear dark burqa-like veils that envelope their entire heads.

Uyghur women often wear long colorful braids and a colorful embroidered, pillbox-type dorha. Dorhas worn by women folk dancers are often black velvet covered with floral patterns made of silver sequins and rimmed by black feathers. These are worn with red long-sleeve dressed with circular skirts worn over tapered silk trousers with embroidery at he ankles and black velvet vests decorated with gold sequins.

Favourite decorations of Uyghur women includes earrings, bracelets and necklaces. Some paint their eyebrows and fingernails on grand festive occasions. They have traditionally had long plaited hair. Married women wore two plaits. Younger girls wore a number plaits that varies according to their age. Girls in the past regarded long hair as part of female beauty. After marriage, they usually wore two pigtails with loose ends, decorated on the head with a crescent-shaped comb. Some tucked up their pigtails into a bun. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Adlis Silk

Uyghur women in Xinjiang have traditionally liked wearing a dresses with Adlis silk in the spring and summer. Black-and-white or red-and-green patterns of silk are regarded as particularly attractive. Uyghurs call the unique colored silk "yubofu nengkanati guli" which means the “crukoo swing flower.” In the past most Aldis silk was made by hand now it is mostly manufactured in factories. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

"Adlis" means “painted silk.” To make it: first bind the threads together, paint color on them, collate them and weave the silk according to different layers. During the painting process, the edge of patterns is permeated with colored dye, with the depth of color and luster determined by how much dye is used. Common patterns include stripes different in width that look like tree branches or water ripples. Some people these patterns may have a connection to ancient and pre-Islamic Uyghur shamanism and the worship of a tree god and water god. ~

Adlis silk is divided into two styles based on different places. One type is from Hetian and Luofu and the other type is from Kashi and Shache. The main colors of Hetian and Luofu are black and white, with black background and white flowers, or a white background and black flowers, or the red-and-white, blue-and-white and black-and-white bottoms with small slices of gold yellow, sapphire blue, jade green or orange between them. The color is simple and lively, the arrangement is tasteful, and the patterns are unconstrained and bold,. The pattern of each cloth has its own characteristics and few of them are similar. Adlis silk in Kashi and Shache is famous for its bright and beautiful color. The patterns are generally stripes of pink, pinkish yellow, jade green, sapphire blue, pale purple, purplish red, and black and white arranged in parallel rows that are different in width. “The structure is fine and close and is decorated with patterns in picturesque disorder.” The sharp color contrasts are “dazzling, and bring a kind of warm, lively and happy atmosphere to people.

Uyghur Colored Hats

Uyghur are known for their colored hats, known as duopa in the Uyghur language. Both men and women throughout the year wear these four-corned squarish hats, which serve as both everyday wear and as a decorative craft worn on special occasions. At festival celebrations and dancing parties and when they visit the friends and relatives, Uyghurs often select their favorite colored hat to decorate themselves. These hats are not only valued decoration but are also valuable gifts for friends and relatives. as souvenir. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

Uyghur hats come in different styles, depending on the areas, occupations, ages and genders of the wearers. In Kashgar area many people like to wear the Bdaanmudoupa. This is made in the shape of the apricot core from Badan wood and decorated mostly with white flowers on black material. In Turfan, each of the four sides of the hat is decorated with the four styles of cloud shapes. The Yili colored worn by both men and women is flat in shape and features delicate simple patterns and elegant colors, In Hetian area, the most famous colored hat is the colored lattice pattern hat for woman. It is wide on the top and narrow at the bottom, with the four corners, and sewed completely using the colorful silk threads. The sewing patterns are tight, harmonious and beautiful. ~

Huke women always wear a little colored hat decorated with protruding pattens made of threads of pearls. These are especially loved by the young women. In the Yutian, Mingfeng and Qiemo areas on the edge of south of Tialimu Valley, Uyghur women like to wear little teacup-shape colored hat about five or six centimeters high and less than 10 centimeters in radius. The Uyghur people call this 'the Taliyabaike'. The top of the hat is covered with colorful silk and made with lambskin trim on the bottom. The craftsmanship is delicate and special. You cannot just put this hat on. Instead, you have to pin it with a scarf . ~

Image Sources: Uyghur image website; All Empires com; Silk Road Foundation; Mongabey; CNTO; Guicida Birmezir

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2015