UYGHURS

Uyghur women Uyghurs are a Turkic-speaking Muslim people who live primarily in the autonomous region of Xinjiang. Described by some as Muslim Mongolians who look like Italian peasants, they are generally larger and darker and have more Mediterranean features than Han Chinese. Blue eyes and light skin are not uncommon among them. Uyghurs mostly follow moderate traditions of Sunni Islam, and culturally have more in common with similar people across Central Asia than with Han Chinese.

The Uyghur (pronounced WEE-gur) are also known as the Uygur, Uighur, Uigur, Weigur,Aksulik, Kashgarlik, and Turfanlik. They are one of the largest ethnic groups in China and the largest ethnic group in Xinjiang. They have traditionally occupied oasis cities in western China that were once major caravansaries on the Silk Road trade route. In those days it was said that Uyghur merchants could count in 50 languages. The story of Xinjiang is primarily the story of the Uyghurs. (See Xinjiang).

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: “The Uyghurs are Central Asian people who are ethnically, culturally, linguistically and religiously distinct from Han Chinese. They are distantly related to the people of modern Turkey, where thousands of Chinese Uyghurs live in exile. There about 10 million Uyghurs in China, mostly in Xinjiang, but also scattered throughout the country, where they work in factories and restaurants that are known for their distinctive cuisine based around lamb kebabs and flat bread known as nan. They are generally poorer and less educated than Han Chinese, a result, Uyghur activists say, of linguistic bias and economic marginalization. [Source:Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, May 22, 2014]

Uyghurs are descendants of wolves according to the Uyghur creation myth. Chinese are descendants of dragons according to their creation myth. For the most part Uyghurs didn’t convert to Islam until the 15th century. For five centuries before that the name “Uyghurs” was used to describe Buddhist and Nestorian oasis dwellers in Xinjiang. In official Chinese government propaganda Uyghurs are described as “colorful, quaint folks.”

The Uyghur are the main nationality in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Nanjiang, which is to the south of the Tianshan Mountain, is their main settlement region. "Uyghur" is the name that they call themselves. It means "union", "alliance" and "providing help". Many Uyghurs live in villages and concentrated communities of areas such as Karsh, Hetian, Akesu and Ku'erle, south of Tianshan Mountain in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Others, are scattered throughout Ili north of Tianshan Mountain, Taoyuan, and, Changde of Hunan Province.

Uyghurs are the third largest ethnic group and second largest minority in China. They numbered 11,774,538 in 2020 and made up 0.84 percent of the total population of China in 2020 according to the 2020 Chinese census. Uyghur population in China in the past: 0.7555 percent of the total population; 10,069,346 in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census; 8,405,416 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 7,214,431 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

See Separate Articles: UYGHUR LIFE, MARRIAGE, HOMES AND FOOD factsanddetails.com ; UYGHUR CULTURE. LITERATURE, KNIVES AND HIP HOP factsanddetails.com ; UYGHURS, CHINESE AND ECONOMICS factsanddetails.com ; UYGHUR SOCIAL PROBLEMS AND STREET CHILDREN factsanddetails.com ; XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG EARLY HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG AND CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG SEPARATISM AND HUMAN RIGHTS Factsanddetails.com/China ; TERRORISM IN XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG RIOTS IN 2009 Factsanddetails.com/China ;XINJIANG, URUMQI Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG. KASHGAR Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG KARAKORUM HIGHWAY Factsanddetails.com/China

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Uyghur Photo site uyghur.50megs.com ; Uyghur News uyghurnews.com ; Uyghur Photos smugmug.com ;Islam.net Islam.net ; Uyghur Human Rights Groups ; World Uyghur Congress uyghurcongress.org ; Uyghur American Association uyghuramerican.org ; Uyghur Human Rights Project uhrp.org ; Uyghur Language Uyghur Written Language omniglot.com ; Xinjiang Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Claude Pickens Collection harvard.edu/libraries ; Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Uyghur and Xinjiang Experts: Dru Gladney of Pomona College; Nicolas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch; and James Miflor, a professor at Georgetown University. Henryk Szadziewski is the manager of the Uyghur Human Rights Project (www.uhrp.org). He lived in the People's Republic of China for five years, including a three-year period in Uyghur-populated regions. Henryk Szadziewski studied modern Chinese and Mongolian at the University of Leeds, and completed a master's degree at the University of Wales, where he specialized in Uyghur economic, social and cultural rights

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Uyghurs: Strangers in Their Own Land” by Gardner Bovingdon Amazon.com; “The Uyghur Community: Diaspora, Identity and Geopolitics” by Güljanat Kurmangaliyeva Ercilasun and Konuralp Ercilasun Amazon.com; “Soundscapes of Uyghur Islam” by Rachel Harris Amazon.com; Language: “Language, Education and Uyghur Identity in Urban Xinjiang” by Joanne Smith Finley and Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “The Uyghur Language” by Gulis Aynur Derya Amazon.com; “Uyghur Language: The Uyghur Phrasebook” by Hala Khan Amazon.com; “Uyghur: An Elementary Textbook” by Gulnisa Nazarova and Kurban Niyaz Amazon.com; History: “A Brief Narrative of the Historical and Geographic Attributes of the Uyghur Identity: And Its Substantial Difference from the Turkic Identity and the Turkish Identity” by Mark Chuanhang Shan Amazon.com; “The Turkic Peoples in World History” by Joo-Yup Lee Amazon.com; “Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia” by Ildiko Beller-Hann, M. Cristina Cesàro, et al. Amazon.com; “The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History” by Rian Thum Amazon.com; “A History of Uyghur Buddhism” by Johan Elverskog Amazon.com; “The Tarikh-i Hamidi: A Late-Qing Uyghur History” by Musa Sayrami and Eric Schluessel Amazon.com; “The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia” by Peter Hopkirk Amazon.com; “Uyghur Nation: Reform and Revolution on the Russia-China Frontier” by David Brophy Amazon.com; “Community Matters in Xinjiang 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur” by Ildiko Beller-Hann Amazon.com; Uyghurs and China: “China and the Uyghurs” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com; “Governing China's Multiethnic Frontiers” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com “Uyghurs and China Internal Colonialism” by Christina J Ray Amazon.com; “Autonomy in Xinjiang: Han Nationalist Imperatives and Uyghur Discontent” by Gardner Bovingdon Amazon.com;

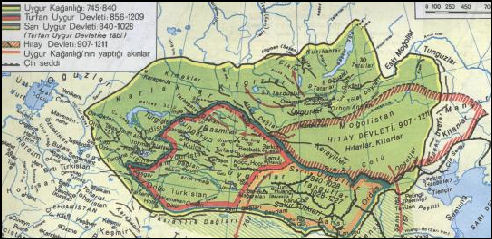

Early Uyghur History

Minaret in Turpan

The Uyghur have a long history, its ancestors can be traced back to the "Dingling" that lived a nomadic life in the wide regions from the Lake Baikal in the east to the Balkashi Lake in the west in the 3rd century B.C. Over the centuries they have been referred to by different translated Chinese names such as Tiele, Yuanhe, Weihe, Huihe, Huihu, Uygu, Uyghur and Weiwur.

In the ancient times, the Uyghurs were mostly nomads that herded animals. After the middle period of the 9th century, they gradually started to become settled farmers, engaging in oasis farming and raising domestic animals. From that time on they were also known main as skilled craftsmen and traders. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

The Uyghurs are descendants of nomads who trace their origin back to the Uyghur knanates, which ruled an area stretching from the Lake Baikal in southern Siberia to the Karakoram more than 1,000 years ago. According to legend the Uyghurs descended from Wugsi, a heroic figure who consumed wine and raw meat as an infant and could walk at the age of 40 days. His grandsons founded 24 clans.

The Uyghurs are regarded as the first Turkic people to settle down, perhaps as early as the A.D. 5th century. In the A.D. 8th century they were under the control of the East Turkic Steppe Confederation. When that fell part they and the Karluks took control of an area in present day western Outer Mongolia and helped the Tang defeat a rebellious general.

In A.D. 840 they were driven from Mongolia by the Kyrzyg and dispersed in many directions. Many settled where the live now in the oasis towns in the Taklamakan Desert, where the Chinese occasionally had a military presence. Near Turfan and Kucha the Uyghurs established a kingdom based on agriculture and trade.

The Uyghurs of this period embraced shamanism, Manichaenism. Nestorian Christianity, and Buddhism. Early Uyghur branches included the Buddhist "Yellow Uyghurs” of Gansu, the Buddhist Karakhoja Uyghurs of Gaochang (present-day Turpan), and the great Muslim Qarakhan dynasty that ruled over much of modern-day Kyrgyzstan, eastern Kazakhstan and western China.

Many Uyghurs were Manichaens, followers of the Persian saint Mani, the “ambassador of light,” who merged Zoroastrian with Christianity. An inscription from one of their ancient cities describes how Manichaenism transformed “this country of barbarous customs, full of the fumes of blood, into a land where people live on vegetables; from a land of killing to a land where good deeds are fostered.”

See Xinjiang History factsanddetails.com .

Later Uyghur History

They Uyghurs had a reputation for fighting among themselves when the Chinese are not around and were regarded as Silk Road middle men, acting as intermediaries between the Chinese and the Central Asian powers. The Uyghurs made a smart decision by choosing to be absorbed by the Mongols rather than fighting against them. In the court of Genghis Khan they acted as diplomats between the Mongols and the great powers of Central Asia. Marco Polo described them as a friendly, fun-loving people.

In the imperial Chinese era, some Uyghur were oasis farmers who developed sophisticated irrigation systems. Some were herders. Many were merchants and traders who worked along the Silk Road.

Some Uyghurs embraced Islam when it arrived in the region in the 9th century but many didn’t convert until after the Mongols did, much later. Some didn’t embrace the religion until the 1450s, long after they adopted Arabic script for writing the Uyghur language. Apa Hoja, a 17th century Uyghur ruler, has become a "symbol of Muslim identity tolerated by the Chinese.”

Uyghur history has been a series of conquests by and rebellions against the Chinese. Many of the Uyghurs in Central Asia moved their during a period of Chinese persecution in he 19th century. They were not unified one leadership until 1884 when the Qing government took control of Xinjiang.

See Xinjiang History factsanddetails.com .

Uyghur Empires

Chinese Take on Uyghur History

The origin of the ethnic group can be traced back to the Dingling nomads in northern and northwestern China and in areas south of Lake Baikal and between the Irtish River and Lake Balkhash in the third century B.C. Some people maintain that the forefathers of the Uyghurs were related to the Hans. The Dingling were later called the Tiele, Tieli, Chile or Gaoche (high wheel). The Yuanhe tribe reigned supreme among the Gaoche tribes during the fifth century A.D., and the Weihe among the Tiele during the seventh century. Several tribes rallied behind the Weihe to resist Turkic oppression. [Source: China.org china.org |]

“These ancient Uyghur people were finally conquered by Turkic Kirghiz in the mid-ninth century. The majority of the Uyghurs, who were scattered over many areas, moved to the Western Region under the Anxi Governor's Office, and areas west of Yutian. Some went to the Tufan principality in western Gansu Province. The Uyghurs who settled in the Western Region lived commingled with Turkic nomads in areas north of the Tianshan Mountains and western pasturelands as well as with Hans, who had emigrated there after the Western and Eastern Han dynasties. They intermarried with people in southern Xinjiang and Tibetan, Qidan (Khitan) and Mongol tribes, and evolved into the group now known as the Uyghurs. |

“The Uyghurs made rapid socio-economic and cultural progress between the ninth and the 12th centuries. Nomadism gave way to settled farming. Commercial and trade ties with central China began to thrive better than ever before. Through markets, they exchanged horses, jade, frankincense and medicines for iron implements, tea, silk and money. With the feudal system further established, a land and animal owners' class came into being, comprising Uyghur khans and Bokes (officials) at all levels. After Islam was introduced to Kaxgar in the late 10th century, it gradually extended its influence to Shache (Yarkant) and Yutian, and later in the 12th century to Kuya and Yanqi, where it replaced Shamanism, Manichae, Jingism (Nestorianism, introduced to China during the Tang Dynasty), Ao'ism (Mazdaism) and Buddhism, which had been popular for hundreds of years. Western Region culture developed quickly, with Uyghur, Han, Sanskrit, Cuili and Poluomi languages, calendars and painting styles being used. Two major centers of Uyghur culture and literature — Turpan in the north and Kaxgar in the south — came into being. The large number of government documents, religious books and folk stories of this period are important works for students of the Uyghur history, language and culture. |

“In the early 12th century, part of the Qidan tribe moved westward from north-east China under the command of Yeludashi. They toppled the Hala Khanate established by the Uyghurs, Geluolu and other Turkic tribes in the 10th century, and founded the Hala Khanate of Qidan (Black Qidan), or Western Liao as it is now referred to by historians. The state of Gao Chang became its vassal state. After the rise of the Mongols, most of Xinjiang became the territory of the Jagatai Khanate. In the meantime, when many Hans were sent to areas either south or north of the Tianshan Mountains to open up waste land, many Uyghurs moved to central China. The forefathers of the Uyghurs and Huis in Changde and Taoyuan counties in Hunan Province today moved in that exodus. The Uyghurs exercised important influence over politics, economy, culture and military affairs. Many were appointed officials by the Yuan court and, under the impacts of the Han culture, some became outstanding politicians, military strategists, writers, historians and translators. [Source: China.org china.org |]

The Uyghur areas from Hami in the east to Hotan in the south were unified into a greater feudal separatist Kaxgar Khanate after more than two centuries of separatism and feuding from the late 14th century. As the capital was moved to Yarkant, it was also known as the Yarkant Khanate. Its rulers were still the offspring of Jagatai. During the early Qing period, the Khanate was a tributary of the imperial court and had commercial ties with central China. After periods of unsteady relations with the Ming Dynasty, the links between the Uyghurs and ethnic groups in central China became stronger. Gerdan, chief of Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang, toppled the Yarkant Khanate in 1678 and ruled the Uyghur area. The Qing army repelled in 1757 (the 22nd year of the reign of Emperor Qian Long) the separatist rebellion by the Dzungarian nobles instigated by the Russian Tsar, and in 1759 smashed the "Batu Khanate" founded by Poluonidu and Huojishan, the Senior and Junior Khawaja, in a separatist attempt. |

“Harsh feudal rule and exploitation gave rise to the six-month-long Wushi (Uqturpan) uprising in 1765, the first armed rebellion by the Uyghur people against feudalism. With the aim of preserving their rule and getting rid of Qing control, Uyghur feudal owners made use of struggles between religious factions to whip up nationalism and cover up the worsening class contradictions. Zhangger, grandson of the Senior Khawaja, a representative of those owners, under the banner of religion and armed with British-supplied weapons, harassed southern Xinjiang many times from 1820 to 1828, but failed to win military victory.” |

Wang Meng in Xinjiang

Silk Road caravan Wang Meng is one of China's best known writers. “In the fall of 1963, Wang applied for a transfer to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, an area in the far west populated mostly by Chinese Muslims,” Jianying Zha wrote in The New Yorker. “He was answering the Party’s call for writers to “delve deep into the grass roots,” but the transfer would also remove him from the turbulent political center. That winter, the Wang family packed their few belongings and boarded a westbound train for the ninety-hour ride. “How long do you think we’ll be there?” Cui asked as the train pulled out of Beijing. “A few years,” Wang replied. “At the most, five years.” Their stay on the western frontier lasted sixteen years. [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

“Xinjiang suited Wang. He marvelled at the region’s beauty: magnificent snow-capped mountains, rocky deserts, towering poplars, lakes that seemed as blue as the sky. He was charmed by the Uyghurs’ approach to life — by the way peasant families grew roses even when they didn’t have enough to eat. He relished the flatbread and lamb that dominated local cuisine, was moved by the melancholy Uyghur songs, and was enchanted by the “symphonic music” of their language. When he discovered that he was the subject of a fengsha — an official ban on a person and his work (the term literally means “seal off to kill”) — he put his energies into learning Uyghur, which was rare for a Han, and won him great affection among the villagers. A daughter was born; Cui and Wang named her for Yining, the Uyghur town where they lived.”

“Wang’s stories about Uyghur life, a series of Chekhov-like tales written in simple, realist language, are among the most moving of his fictional works. Without narrative indulgence, they show an attentiveness to the details of ordinary life, the moody beauty of nature; the tone is of gentle comedy and black humor amid disaster. Reading them, you could feel Wang’s genuine respect for a culture and a people.”

“In 1966, Mao launched the Cultural Revolution. In Beijing and other big cities, the Red Guards ransacked homes, burned books, and beat up teachers, sometimes torturing and killing them. In Yining, Wang burned all his personal correspondence. But geography did help insulate him; the campaign had lost much of its severity by the time it reached the remote border town, and Wang was protected by his Uyghur friends. An elderly peasant who sheltered him said, “Don’t worry, Old Wang, any country needs three kinds of men: the king, the courtesan, and the poet. Sooner or later, you will return to your post as a poet.”

Uyghur Population

Uyghur population in China: 0.7555 percent of the total population; 10,069,346 in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census; 8,405,416 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 7,214,431 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. Uyghurs can have more than one child, and most couples usually have two or three. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

About 8.5 million of the 10 million Uyghurs live in Xinjiang. Those that live outside Xinjiang are mostly male traders that live in Chinese cities. Around 400,000 Uyghur are living outside of China, mostly in Central Asian states bordering Xinjiang. There are about 300,000 in Kazakhstan, 50,000 in Kyrgyzstan. There are also some on Pakistan, Afghanistan, Turkey and the West. Many of the Uyghur in the United States are in the Washington D.C. area and Oklahoma.

Uyghurs make up 45 percent of the population of Xinjiang compared to 75 percent in 1945. Although their numbers have been diluted in northern Xinjiang by Han Chinese settlers and are now outnumbered there the Uyghurs are still the majority in southern Xinjiang. Han Chinese have grown from 9 percent of the population of Xinjiang in 1945 to 40 percent today.

Uyghurs live mostly to the south of the Tien Sien mountains in the districts of Hotan, Kashgar, Turfan, Aksu and Korla, where they occupy oasis land on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert and Tarim Basin. In 1949, Uyghur made up 93 percent of the population of Urumqi. Now they make up about 50 percent. Forty percent are Han Chinese.

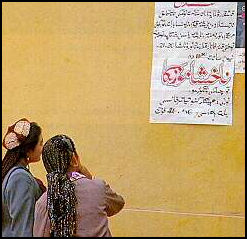

Uyghur Language

Reading a sign in Uyghur

Uyghurs speak an Altaic language similar to Uzbek and Turkish. Some words are the same in Uyghur and in Turkish. “Bir, Iki, Uech, Doert, Besh”, for instance, are one, two, three, four and five in both Uyghur and Turkish. Most speak Chinese. Some speak it very well. Some are just minimally conversant. Some speak Arabic and Turkish fluently yet speak only a little Chinese. Many elderly Uyghurs can’t speak Chinese at all. Many Uyghur traders can speak a half dozen languages, including Uyghur, Chinese, Russian, Uzbek, Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Turkish.

Uyghurs speak an Altaic language. Mongolian, Kazakh, Manchu, Kyrgyz, Turkish and other Altaic, Tungusic and Turkic languages are Altaic languages in the Ural-Altaic family of languages. Some linguists believe they are related. Other believe they share similarities because of the borrowing of words by traditionally nomadic peoples. Ural-Altaic languages include Finnish, Korean and Hungarian.

The languages of the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Mongols and Uyghurs are so similar that they can easily communicate with each other and often eat and party together when they live near one another. These languages are difficult to learn and speak. Travel writer Tim Severin wrote they sound “like two cats coughing and spitting at each other until one finally throws up..” Some of the more guttural sounds sound like someone is having difficulty breathing.

Flight attendants on flights to Xinjiang speak English but not Uyghur. On trains in Xinjiang only Chinese is spoken. To get gain entrance into a Chinese university and get a good job, the Muslim minorities in Xinjiang have to pass Chinese-language examinations. The people of Xinjiang also resent having Mandarin names attached to their ancient ruins. When Uyghurs do speak Mandarin they are often mocked for their accents by Han Chinese.

Uyghur Written Language and Names

Uyghurs has traditionally written with Arabic script that appeared in the 13th century and has been adapted to accommodate Uyghur sounds not found in Arabic. Ancient Uyghur writing, abandoned long ago, was based on the alphabet of the Sogdians, a Persian people centered around Samarkand in the A.D. 6th century. This language provided the basis for Mongol script used from era of Genghis Khan until it was replaced by Russian in the 1940s.

In the early 13th century, under Genghis Khan, the Mongols created a vertical script based on the Uyghur script, which was also adopted by many Turkic-speaking peoples and is related to the alphabets of Western Asia. It looks like Arabic written at a slant.

The Uyghur script is related to the alphabets of Western Asia and has been adopted by many Turkic-speaking peoples. Zhuang, Tibetan, Uyghur and Mongolian are official minority languages that appear on Chinese banknotes. Many Uyghur can use the Arabic alphabet. Some Uyghur children learn Arabic script in primary school. Others learn Arabic written in Roman letters. Most secondary school classes are taught exclusively in Chinese.

The Uyghur language in Pinyin is based upon Arab. After the founding of Communist China, a new form of characters based on the Latin alphabet was devised but it never really caught on.

Many Uyghurs have only one name. On the name Ilham Tohti, a persecuted Uyghur scholar, Chinese activist and scholar Wang Lixiong told the New York Review of Books: “ His real name is just Ilham. For Uyghurs, the second name isn’t their family name; it’s their father’s name. So if you call him Tohti or Mr. Tohti, you’re addressing his father! The meaning of the name Ilham Tohti is “Tohti’s son, Ilham.” But if Ilham had a son say named Mehmet, his name would be Mehmet Ilham, not Mehmet Tohti. [Source: Ian Johnson,New York Review of Books, September 22, 2014]

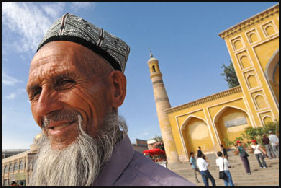

Uyghur Religion

Uighur Muslim outside

a mosque in Kashgar

Nearly all Uyghurs are Muslims. Some are devout; others are Muslims in name only. Uyghurs embracing Buddhism are called Yughur, one of the China’s officially recognized nationalities. Muslim Uyghurs have far more affinity for their Central Asian brethren in neighboring Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan than for the Han majority to the east.

Uyghurs are known for practicing a moderate form Sunni Islam with a mystical Sufi tradition. Many drink alcohol and have no objections to women working. It is not unusual to see young Uyghur women in the cities dressed in designer jeans and high heels. Ilham Tohti said, ‘Nowadays, more and more Uyghur youngsters are leaving Islam. They drink alcohols, steal things and the traditional morals and customs are being destroyed’.

Islam is important to the Uyghur’s identity but is not very deep rooted as a religion. Most Uyghur are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school. Some are followers of Sufi sects. The worship of Islamic saints (mazar) is widely practiced. Many Uyghurs visit the tombs of popular holy men. Uyghur Sufis chant sacred words. Whirling-dervish-type rituals are performed in front of mosques in Kashgar.

Uyghurs have traditionally followed a moderate form of Islam but many have begun adopting practices more commonly seen in Saudi Arabia or Afghanistan, such as full-face veils for women. Uyghurs have traditionally been wary of Muslim extremist and Islamists. On the Uyghurs, one Afghan fundamentalist told the New Yorker: “They’re the same as Communists.”

Corban, Ramadan and Eid are the biggest Uyghur festivals. Many also celebrate the Spring Festival (Chinese New Year). The traditional festivals of Uyghur people include the Rouzi (Eid), Gu'erbang and Chuxue Festivals (celebrated at the first fall of snow). Rouzi Festival is also called Kaizhai. Gu'erbang Festival (Corban) is a traditional festival held 70 days after Rouzi Festival. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

Shamanist and animist traditions endure. In some places shaman chant Koranic passages to heal the sick and people wear amulets with Arabic script to ward off evil spirits. In the old days there were descriptions of shaman dancing around ropes hung from ceilings, chanting Koranic verses and beating patients with dead chickens to exorcize evil spirits. Some Uyghurs shave the heads of the babies, leaving being hair carved into wild designs, a pre-Islamic shamanistic practice to scare away baby-stealing spirits.

See Xinjiang Religion

Uyghurs celebrate Muslim holidays and practice ground burials. In Kashgar there are unusual beehive-shaped tombs, with little windows.

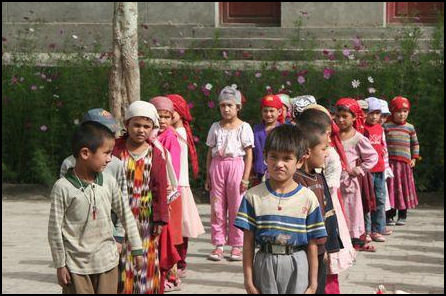

School kids in Kusrap

Chinese Take on Uyghur Religion

According to the Chinese government: “Over the centuries, many mosques, mazas (Uyghur complexes, nobles' tombs), theological seminaries and religious courts were set up in Uyghur areas. Over the past few hundred years, religion has greatly influenced economic, judicial and educational affairs and the Uyghur family and matrimonial system. Some of the rich people made use of religious rules to marry more than one wife, and had the right to divorce them at any time. The marriage of the ordinary Uyghurs was mostly arranged by the parents. Male chauvinism was practiced in the family, and Uyghur women, humiliated and with nobody to turn to, often retreated into prayer. [Source: China.org china.org |]

“After 1949, feudal religious privileges were abolished, and religion was taken out of the control of the reactionary ruling class, and became a matter of individual conscience. As science and knowledge spread, many of the old feudalistic religious habits lost popularity. People can now decide for themselves whether the Sawm should be observed during Ramadan, how many naimazi (services) should be performed in a day and whether women in the street should wear veils. As these matters do not affect normal religious belief, the Uyghurs are beginning to enjoy a more genuine religious freedom. The family, marriage and property are under the protection of the law, and Uyghur women enjoy equality with men. Many are now working alongside men in modern industries.” |

Image Sources: Uyghur image website; All Empires com; Silk Road Foundation; Mongabey; CNTO; Guicida Birmezir

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022