XINJIANG AND CHINA

Mao statue in Kashgar Beijing regards Xinjiang as an integral part of China and an important strategic area for defense. It also very interested in the large deposits of oil and natural gas in the area.

Some people refer to western China and Turkish-speaking countries in Central Asia as Turkestan ("Land of the Turks"). It is a term laden with Islamic and separatist connotations. Using it in China can land someone in a labor camp.

An often heard phrase in western China is "The mountains are high and the emperor is far away." This refers to the geographical distance and cultural differences between Xinjiang and Beijing. It is also often said that China ends and Turkestan begins where the Great Wall ends in Gansu Corridor of north-central Gansu Province.

According to AFP: “Beijing's propaganda portrays the vast and remote western region of Xinjiang as a harmonious land of colourful, mostly Muslim Uyghur natives and hard-working migrants prospering under Communist Party rule.” Associated Press says: “While the dream of a new Silk Road speaks of open borders and the free movement of people and goods, China’s response to that discontent and violence has been a tightening of its already strangling controls over Xinjiang: mass surveillance and closed borders, ever-stricter controls on religious practice and a “strike hard” campaign against extremism that has resulted in hundreds of arrests and more than 20 executions since May, all on terrorism-related charges.

See Separate Articles under Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Xinjiang: China's Central Asia” by Jeremy Tredinnick Amazon.com; “Xinjiang and the Modern Chinese State” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com “Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland” by S. Frederick Starr Amazon.com; “Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang” by James Millward Amazon.com; “The Cultures of Ancient Xinjiang, Western China: Crossroads of the Silk Roads” by Alison Betts, Marika Vicziany, et al. Amazon.com; “Land of Strangers: The Civilizing Project in Qing Central Asia” by Eric Schluessel Amazon.com; “The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia” by Peter Hopkirk Amazon.com; “Securing China's Northwest Frontier” by David Tobin” Amazon.com; Repression, Xinjiang and the Uyghurs: “The War on the Uyghurs: China's Campaign Against Xinjiang's Muslims” by Sean R. Roberts, Christopher Ragland, et al. Amazon.com; “Waiting to Be Arrested at Night: A Uyghur Poet's Memoir of China's Genocide” by Tahir Hamut Izgil, Joshua L. Freeman Amazon.com; “Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City” by Darren Byler | Amazon.com; “We Uyghurs Have No Say: An Imprisoned Writer Speaks” by Ilham Tohti, Yaxue Cao Amazon.com; “Middle Country: An American Student Visits China's Uyghur Prison-State” by Grayson Slover Amazon.com; Camps: “The Xinjiang emergency: Exploring the causes and consequences of China’s mass detention of Uyghurs” by Michael Clarke Amazon.com; “How I Survived A Chinese 'Re-education' Camp: A Uyghur Woman's Story” by Gulbahar Haitiwaji and Rozenn Morgat Amazon.com; “The Chief Witness: Escape from China's Modern-Day Concentration Camps” by Sayragul Sauytbay, Alexandra Cavelius, et al. Amazon.com; Genocide: “No Escape: The True Story of China's Genocide of the Uyghurs” by Nury Turkel Amazon.com; Menace: China’s Colonization of the Islamic World & Uyghur Genocide by Abdulhakim Idris Amazon.com; “Worse than Death” by Mamtimin Ala Amazon.com; “100 Camp Testimonies: Arbitrary Incarceration, Forced Labor, Forced Abortion/Sterilization, and Forced Family Separation” by Erkin Kâinat Amazon.com

Time Difference in Xinjiang

People in Xinjiang are supposed to Beijing time even though Beijing is four time zones away. If one were to follow Beijing time exactly in Xinjiang one would wake up hours before sunrise and go to bed at sunset. According to Beijing time, the sun rises in Kashgar in midwinters at 10:00am and sets is the summer at 11:00pm.

Most Uighurs ignore Beijing time but many Han Chinese use it, albeit with a few alterations. A Han student in Kashgar told the Los Angeles Times, “Most people are using Beijing time; only local Uighurs use Xinjiang time. But our class starts two hours later than usual time. It is quite easy to adapt to it, just as when you are in Rome, do as the Romans do.”

In 1968, Long Shujin, the hardline Communist Party secretary of Xinjiang, issued a decree ordering Uighurs to stop using their own time. But the Chinese government could not enforce the law. In 1986, a small notices was quietly published that gave tacit approval to the use of local time. In Xinjiang today, local time remains officially unofficial. Many Uyghurs set their watches two hours earlier than the official time, making the sun in winter rise sensibly at around 7.30 am rather 9.30 am as the Communist Party prescribes. In some hotel lobbies there are still clocks with the local times in New York, Moscow, London, Tokyo and Beijing but not Xinjiang. When asked why there was no clock for Xinjiang at his hotel, one hotel employee told the Los Angeles Times, “there’s no need; they know what time it is.” An Uighur watchmaker, who tried to sell a watch that displayed both times but withdrew it because nobody bought it, said, “People use one time or the other, not both. The Chinese use Beijing time, the Uighurs use their time. But if somebody buys a watch from me, I’ll set it however they like.”

Chinese Policy in Xinjiang

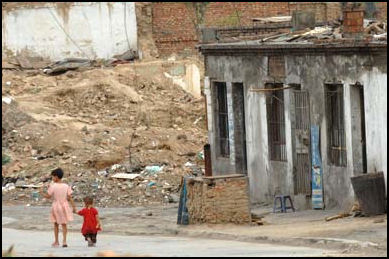

Muslim slums in Urumqi

The Chinese use carrot and stick approach to Xinjiang, providing development and jobs while cracking down hard on dissent. Their goal is to create a generation of Mandarin speakers with stronger ties to China and less strong ties to Islam. There are programs, for example, in which the best and brightest Uighurs are sent to Mandarin-only schools in other provinces.

China reacted to the 2009 riots by pumping money into less-developed southern Xinjiang, in an implicit recognition of the economic causes of the unrest. But it has taken a much harsher line of late, especially towards dissenters.

Ilham Tohti wrote: No good political intentions or political desires can be divorced from the meticulous and thorough technical designs that support them. In China especially, the government is accustomed to large-scale government-directed organization and mobilization of social resources without regard for the costs, rather than long-term and patient technical arrangements. Looking at the examples of multiethnic diversity in Malaysia and Singapore, a technically meticulous, evenhanded management of ethnic interests produces ethnic tolerance and harmonious relations. That’s why I have always believed in the importance of my own endeavors. Furthermore, from a geostrategic perspective, China must research how to effectively exert influence in the political, economic and cultural spheres of Central Asia, not only so that it can benefit from an enhanced regional security environment, but also so that both China and Central Asia can build stronger, mutually beneficial relations. This is another aspect of my interests in the region. [Source: Ilham Tohti, January 17, 2011, published in China Change, April 6, 2014 ~]

See Religion Under Xinjaing

Softer Chinese Policy in Xinjiang in the Past

Kelly Olsen of AFP wrote: “Relations between the central government and peripheral regions were once more fluid, but since the Communist Party gained power in 1949 rigidity has become the rule, and all Chinese must carry identity cards that prominently state their ethnicity. Some leading communist officials in the past have pushed for a softer line on ethnic issues, University of Hong Kong scholar Willy Lam said, including former party general secretary Hu Yaobang and Xi Zhongxun, the late father of current President Xi Jinping. But there is no support now for that approach, he said. [Source: Kelly Olsen, AFP, July 3, 2013]

Ilham Tohti wrote: “People in Xinjiang today generally look back nostalgically at ethnic relations during the planned economy era [1949-1976] as well as Hu Yaobang and Song Hanliang era [1976-1989]. During the planned economy era, the government distributed resources equally and fairly, creating a positive sense of equality among ethnic groups. In addition, at that time the population was restricted in mobility and there were few opportunities for group comparisons that could result in a sense of inequality. During the Hu Yaobang and Song Hanliang era, the political climate was relaxed. On the surface more people seemed to be voicing discontent publicly, but people trusted each other and felt least suppressed, and social synergy was the strongest. [Source: Ilham Tohti, January 17, 2011, published in China Change, April 6, 2014 ~]

Beijing’s Effort to Win Hearts and Minds in Xinjiang

Beijing also hopes to win hearts and minds in Xinjiang by raising incomes, improving infrastructure and creating more opportunities. Dru Gladney, a professor of Asian Studies at the University of Hawaii, told the Washington Post, "There is a feeling that the Chinese government has given and given to Xinjiang and all they get is criticism. "

For decades the Chinese government has given Uighurs benefits not available to Han Chinese The non-Han-Chinese people in Xinjiang are allowed to ignore the one-child policy and have three children if they live in rural areas and two if they live in urban areas. They pay virtually no taxes; farmer receive tax-free leases on land; and low-interest loans are available. The people of Xinjiang are afforded the same affirmative action policies — preferences for university admission and government promotions — given other minorities. Students are given extra points on university entrance exams. The radiators and thick carpets in Kashgar’s Id Kah mosque, the largest mosque in China, were paid for by the Chinese government.

According to Reuters: “While Beijing insists there are no flaws in its ethnic policies, the top leadership has made some adjustments. It has agreed to provide free high-school education in southern Xinjiang, which has the highest concentration of Uyghurs, and promised employment for at least one member of each household.” [Source: Reuters, May 14, 2014]

Tom Phillips and Malcolm Moore wrote in The Telegraph, “In an implicit recognition that the social chasm between Han Chinese and Uyghurs has played a role in Xinjiang’s troubles, Beijing unveiled a raft of measures aimed at combating poverty among Xinjiang natives. They include a job creation scheme ensuring "that at least one person from zero-employment families is offered a job," Xinhua reported. A massive heart-and-minds campaign, by which tens of thousands of officials are being sent to rural areas to provide aid, is also underway. "We want all villagers to enjoy the achievements of China's fast economic growth," Sun Hua, a Communist Party official who has been dispatched to a village near the city of Kashgar, told the China Daily. [Source: Tom Phillips and Malcolm Moore, The Telegraph, May 27, 2014]

Terrorism, the Military and China’s Policy in Xinjiang

Bordering on Pakistan, Afghanistan and several unstable Central Asian states, Xinjiang is prone to unrest and violence blamed on radicals among the Uyghur population who have been waging a low-intensity insurgency against the Chinese government for decades. Uyghur activists say economic marginalization and cultural and religious restrictions are fueling the violence, while Beijing blames overseas-based instigators. [Source: Associated Press, November 4, 2013]

According to Associated Press: While counter-terrorism is mainly the responsibility of the police and paramilitary People's Armed Police, the military plays an especially influential role in Xinjiang. Military units there operate as de facto governments over certain cities and vast amounts of farmland and mining operations, maintaining their own police and courts.

Alim Setoff of the of the Uighur American Association told the Los Angeles Times: “China has been very successful at portraying Uighurs as terrorists and themselves as victims of terrorism, while they manipulated Islam through their control over mosques. It’s really not easy trying to stand up to such a powerful country and emerging superpower.”

Sean Roberts, a George Washington University professor specializing on Chinese and Central Asian affairs, told Al-Jazeera that it appears that Beijing's current methods are less than effective. “Putting myself in the position of Chinese bureaucrats, their strategy is not working, so they are pushing it harder and harder. And their strategy is only exacerbating the problem.” Tohti offered his own suggestions for a new strategy. “If China really believes Uyghurs are part of the country, then meet your responsibility to them. Uyghurs are impoverished and have no rights. China needs to improve their living standards,” Tohti said. [Source: Massoud Hayoun, Al Jazeera America, September 18, 2013 \^/]

China’s Heavy Handed Policy in Xinjiang After 2013-2014 Terrorist Attacks

After a series of terrorist attacks in late 2013 and 2014, Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “Alarmed by increasingly violent resistance to its policies, the Chinese government has embraced an even more heavy-handed approach: ramped-up Han migration to the region, restrictions on Islamic religious practice, a Stalinist-style police state and educational policies that seek to make Mandarin the lingua franca. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, May 12, 2014 |=|]

Nicholas Bequelin, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch in Hong Kong, said the Chinese leadership has come to view the promotion of Uyghur culture and identity as a covert effort to foment disloyalty to Beijing and subvert the drive for assimilation. “The Chinese state appears to place no value on the Uyghur way of life and traditions beyond the Disneyfied version it offers to tourists,” he said. “Every other aspect of Uyghur life must be either destroyed, remodeled or neutered so as to prevent it from becoming a potential vehicle for Uyghur ethno-national aspirations.” |=|

“Exile groups and rights advocates said they feared the recent bloodshed would lead to even tighter security measures in Xinjiang and shrink the already narrow space for discourse about Beijing’s policies in the region. Uyghur intellectuals have long bemoaned the Communist Party’s stranglehold on free expression, especially that which strays from the official narrative portraying Uyghurs as an exotic people, fond of dancing and singing, who are deeply appreciative of the party’s benevolent embrace. |=|

Human rights activist and lawyer Teng Biao, a co-signer of the "Charter 08" movement calling for better rights guarantees, criticized Beijing's "barbaric minority policy," calling it a catalyst for conflicts in which the innocent suffer the most. At the center of the struggle for the hearts and minds of Xinjiang may be historical factors, but Teng has argued that those in charge should be held accountable for exacerbating problems. He has singled out "those who want to totally destroy southern Xinjiang," the center of the Uyghur population, as well as those who belittle the Uyghurs — and even the general public, which has shown little concern for what is happening in China's westernmost expanses. [Source: CNA, Want China Times, March 5, 2014 /*/]

Communist Leadership in Xinjiang

Willy Lam wrote in China Brief: "Xinjiang Party Secretary Wang Lequan once opined that the Turkic-like Uighur language was out of step with the 21st century. Since being posted to Xinjiang in 1991, Wang has relentlessly promoted a Sinicization policy aimed at making Uighurs more like ordinary Chinese. Wang’s performance so impressed the CCP leadership that this former head of the Shandong Branch of the CYL was awarded Politburo status in 2002. That Wang has stayed in Xinjiang for 18 years, however, goes against the time-honored CCP personnel policy of not allowing a local chieftain to remain in the same jurisdiction for more than five to six years." [Source: Willy Lam, China Brief, July 23 2009]

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “The long-serving party chief of Xinjiang, Wang Lequan, was replaced in 2010, following a surge in violence in the region. Some Uighurs held out hope that the new party leader, Zhang Chunxian, the top official in Hunan Province, would adopt a softer line and try to examine the discriminatory policies that have led to the rise in ethnic tensions. But cycles of crackdown and violence have continued. Last July, clashes erupted in the towns of Hotan and Kashgar, which lie on either side of Yecheng County. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, February 29, 2012]

“Zhang Chunxian brought a new style, but the policies haven’t changed,” Nicholas Bequelin, a senior Asia researcher for Human Rights Watch, told the New York Times. “They were laid out at the Xinjiang work conference in 2010. These policies promised a rapid boost to the local economy — which has happened — but absent from this blueprint were the issues that top the list of the Uighur discontent: discrimination, Han in-migration and the ever-more invasive curbs on language, culture, religious expression.”

Mr. Bequelin added that the one notable change since Mr. Zhang took office is that there is a greater recognition that socio-economic discrimination against Uighurs needs to be addressed. “But not much has been done in this respect, and the polarization between Uighurs and Chinese continues to grow,” he said.

Xi Jinping’ Hardline on Xinjiang

On the beginning of the harder line against Uygur moderates, Teng Biao, a good friend of Ilham Tohti and a lawyer who teaches at the University of Law and Politics in Beijing and has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University, told the New York Review of Books: March of 2013. This was when Xi Jinping formally took over [as president of China, after assuming control of the party the previous autumn]. On March 31 they arrested the Four Gentlemen of Xidan [four activists who met in the Xidan area of Beijing: Yuan Dong, Zhang Baocheng, Li Wei, and Hou Xin]. Since then hundreds of human rights defenders, such as the New Citizens Movement, or Pu Zhiqiang or Ilham. Before that their purpose was to control civil society—to arrest those who are active, or who cross the red line. I mean people like Pu Zhiqiang or Hu Jia or Chen Guangcheng—those who are active or influential and those the government cannot tolerate. But now it seems that their purpose is to destroy the ability of civil society to exist. So many human rights activists have been arrested, including those who have not been so active, but who are potential leaders. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, September 22, 2014]

During a highly publicized tour of Xinjiang in April 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping pushed forward the message of integration and stability, urged Uyghur students to devote themselves to Mandarin and praised security forces involved in policing and crackdowns in Uyghur areas. “The battle to combat violence and terrorism will not allow even a moment of slackness, and decisive actions must be taken to resolutely suppress the terrorists’ rampant momentum,” Xinhua quoted him as saying. After Mr. Xi’s appearance, a train station in Urumqi, the regional capital, was attacked, perhaps in response to him being in the region. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, May 12, 2014 |=|]

During his April 2014 tour of Xinjiang, Xi was quoted as saying that the long-term stability of Xinjiang was vital to the entire country’s “unity, harmony and national security, as well as to the great revival of the Chinese nation.” In a major speech on Xinjiang on month later, Xi vowed to promote ethnic unity and provide more jobs for local people. But at the same time, an intensified crackdown on conservative Islam has sparked resentment among many Muslim Uyghurs. [Source: Simon Denyer, Washington Post, September 10, 2014 /=/]

Simon Denyer wrote in the Washington Post, “Xi has effectively doubled down on China’s long-standing policy toward Xinjiang, a strategy that has three fundamental strands: strict control meant to identify and eliminate separatists; massive economic investment meant to win over other people; and a large-scale migration of China’s majority Han people into Xinjiang — an ethnic dilution of the Uyghurs’ hold on what they consider to be their homeland.” /=/

Chinese Propaganda and the Xinjiang Exhibition

Beijing uses heavy does of propaganda and indoctrination in Xinjiang. Banners hung in Kasghar read: “All ethnic groups welcome the party’s religious policies.” Some Uighur civil servants are required to take ideology classes for two hours a day that aim to teach the glories of the Communist Party, the dangers of separatism and the benefits of a unified China. They are also required to sing a song that drives home he latest party slogan: “Eight Virtues and Eight Shames.” One Uighur civil servant told the Los Angeles Times. “At work I have to say, “I love everything Han Chinese — or I get into trouble."

A state-sponsored exhibition of ancient books, documents and seals opened in August 2010 at the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Museum in Urumqi. Organized by the China National Preservation and Conservation Center for Ancient Books in the National Library of China, it was the first comprehensive exhibition of this kind since 1949 and included 106 items that date back to 4,000 years ago and up to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). [Source: Guo Shuhan, China Daily August, 18 2010]

Among the items displayed were Accounts of the Western Regions of the Great Tang Dynasty, written by Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) Buddhist master Xuanzang in and 646, after his pilgrimage to India. A transcript of Xuanzang's work was made soon after the original was completed. Researchers say it was the earliest copy of the work and was offered to Turpan, an important trade center on the Silk Road.

Propaganda Murals of Xinjiang

The target of its crackdown in Xinjiang, the Chinese government says, is “terrorism driven by religious extremism”. Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Uplifting propaganda posters touting President Xi Jinping's "China Dream" catchphrase are plastered across many cities in China these days. But throughout the country's westernmost province, an unrelenting series of billboards, red banners and spray-painted signs suggests menace lurking everywhere. "It is strictly forbidden to transmit violent terrorist videos," warn banners hung from government buildings and draped across traffic lane dividers. "Young men should not grow beards and young women should not cover their faces with veils," some signs read. The messages make it clear whom authorities blame for the explosions, knifings, riots and other violent incidents that have left hundreds dead this year in Xinjiang province: Islamic extremists and separatists with ties to foreign forces.” [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, October 26, 2014]

According to the BBC: “Part of the campaign includes murals painted on the walls in places like mosques in the old town of Kashgar. They show what the Chinese government deems as acceptable and unacceptable behaviour. It is not clear who paints these posters, but their presence implies they have some kind of official approval. Throughout these murals, “bad” Uyghurs are painted in black and grey while “good” law-abiding Uyghurs are painted in bright colours and flanked by doves, a symbol of peace. [Source: BBC News, January 12, 2015 |::|]

One mural shows a Chinese cement roller crushing knife-wielding Uyghurs painted in black, accompanied by the Chinese proverb: “A mountain of knives and a sea of fire”. Many of the recent violent attacks in Xinjiang and beyond have involved knives. Another mural is painted on the walls next sayss terrorists must be chased down like rats in the street. A similar image shows an axe with the National Emblem of the People’s Republic of China crushing terrorists, again appearing in sinister black. Elsewhere in the Kashgar’s Old City propaganda slogans read: “Everyone has the responsibility to create peace and security.” [Source: New York Times, |::|]

One mural shows armed guards flanked by peaceful doves. In front of a Chinese flag, Uyghurs read a Chinese book. Another mural says Uyghur children should attend school and not go to mosque. This will keep them away from evil jihad as represented by the sinister Uyghur in the left of this mural. Another shows an imam marrying a Uyghur couple in secret. This is against Chinese law. An Uyghur man on the right is holding up a book on Chinese marriage law. |::|

The government has started a campaign called “Project Beauty”. Only older Uyghur men are allowed to have beards while Uyghur women are banned from wearing full veils. In one mural Uyghur women are encouraged to show their face – to give their beauty to the world. Another mural depicts the Chinese government’s desire for a harmonious society represented by a woman in traditional Han – the ethnic majority in China – dress dancing happily with a Uyghur woman. |::|

Princess Fragrant Cartoon Aims to Ease Ethnic Tensions in Xinjiang

William Wan and Xu Yangjingjing wrote in the Washington Post, “With the encouragement of the authorities, a Chinese animation company is turning to a Disney-like character for help in bringing ethnic Uyghurs and Han Chinese together. “Princess Fragrant” is a 104-episode show based on the historic figure Ipal Khan. Its creators said they think the story of a princess from the Uyghur Muslim minority who married a Chinese emperor in the 18th century could ease the ill will on both sides — or at least begin that process with the next generation. [Source: William Wan and Xu Yangjingjing, Washington Post, August 25, 2014]

“Since August 2013, the animation company Shenzhen Qianheng Cultural Communications has spent more than $3 million producing the 3-D princess cartoon, which will air in 2015 in Mandarin and Uyghur. The company, based far from Xinjiang in the southern city of Shenzhen, is taking part in a government program that pairs 13 inland Chinese cities with cities in far-western Xinjiang in an effort to spur development. Deng Jiangwei, director of the cartoon, said the animators chose to focus on Princess Fragrant — rendered with classic Disney-pixie cuteness and wide-eyed innocence — because of her historic contributions to ethnic unity and stability. She remains highly regarded in both Uyghur and Han Chinese societies.

“In the cartoon, Princess Fragrant and her friends set out on an adventure to find her father, who was abducted by “evil forces” from the West. The villain was after a family heirloom, which turns out to be spiritual rather than monetary. The company approached the Kashgar government in 2013 with the idea. Government officials eagerly welcomed the idea and promised funding, but the company has not yet received state financial support, Deng said. The company set up offices in Kashgar, and one-third of the employees there are Uyghurs. Most members of the design team in Shenzhen are Han Chinese, although for the cartoon they traveled in Xinjiang in an attempt to better understand its culture and history, and local experts were included to correct errors in their work, Deng said.

“Deng said they had to avoid making too many references to Islam in the cartoon, even though Princess Fragrant was a Uyghur. “We cannot promote religion in our work, but we do refer to some aspects of the Islamic culture, such as etiquette, things that are easily acceptable to most people,” Deng said. He described their challenge as finding a balance between authentic Islamic culture and an entertaining story. Despite their overt political aim, the producers said, they tried not to get too preachy in the message. “It’s about family and growing up,” Deng said.

The princess is not the first cartoon character called upon to promote ethnic unity. Last year, Xinjiang children were treated to the TV series “Legend of Loulan,” about an ancient kingdom swallowed by shifting sands. It featured characters of different ethnicities banding together to beat a sand monster and save the kingdom. Huang Zhiyong, who directed the Loulan series, said: “Kids are impressionable, and they like to imitate. Things they see on TV can greatly influence their values.” The show aired last year in Mandarin only — a notable fact in the face of Uyghur accusations that the government is trying to replace their traditions and language with Chinese ones. Huang said it is now in the process of being dubbed in Uyghur.

Chinese Development in Xinjiang

Government-constructed house

The Chinese in many ways have helped the people of Xinjiang progress and modernize at a great expense. Before the arrival of the Chinese, there were few roads, hardly any electricity, no modern medicine and no education outside the mosques in Xinjiang. Many people lived under warlords in feudal arrangements. The Chinese introduced land reform and brought paved roads, electricity and running water. Under the Chinese, life expectancy has increased, a greater variety of food has become available, and the levels of illiteracy have been greatly reduced.

The Chinese have a hard time understanding why the schools, factories and roads they built are not appreciated. What they have failed to realize it seems is that the people of Xinjiang do not want their help and would rather modernize and progress on their own terms.

Massive urban renewal projects have resulted in the demolition of traditional Old-City- neighborhoods and their maze of alleys and have forced Uighurs out of their traditional mud brick houses into Chinese-style apartments in the suburbs.

The people of Xinjiang are increasingly torn between their desire to get rid of the Chinese and their dependence on the jobs, opportunities and development that the Chinese bring. Some are glad to get the roads and railroads but also complain they just allow more Han Chinese to flow in and take the good jobs.

Tearing Down the Old City of Kashar, See Separate Article

Go West Program in Xinjiang

Xinjiang has been ground zero of the Go West program, launched in 2000 with the aim of developing and modernizing the poor western parts of China and reducing the income gap between western China and the more developed parts of the country and spreading the economic wealth from the coastal provinces and helping the people in impoverished areas in the interior of China. According to the original plan the Communist government allocated $106 billion for 60 major projects, including rail and road expansions, hydroelectric dams, and oil pipelines. Not only workers but highly educated engineers, entrepreneurs, professors and IT personnel left for the relatively poor western provinces, leaving behind larger paychecks and comfortable lifestyles in the east.

The "Go West" program was started in the late 1990s by the administration of former President Jiang Zemin. Highways were built, houses were constructed , nomads were resettle in “model” villages. Million were give access to electricity and clean water. New rail lines were built to Lhasa in Tibet and Kashgar in Xinjiang. As of 2006, thirty-one projects had been completed at a cost of $56 billion. These include the new railway to Kashgar, new highways through the Taklamakan Desert, electricity grids, several factories, a heating plant and a copper smelter.

working at night in Xinjiang in the 1950s

Who Has Benefited from Go West?

Many feel that ultimately the program has helped Han Chinese more than it has the people in Xinjiang. Zhap Baotong of the Shaanxi Academy of Social Sciences in Xian told the Washington Post, “among the key projects of the Go West program, the majority only benefit the east. These projects are transporting electricity, natural gas and other resources from west to east to fuel development there.”

Even though western China has chalked up 12 percent economic growth rate it remains the poorest least-developed, and least-educated part of the country. The government has boasted of promoting pharmaceuticals and handicrafts in the region but the overall impact of these industries has been relatively small.

Keith Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “The massive investments, critics say, has mainly benefited state-owned companies that build the roads and railways and mine the minerals. There is little indigenous industry and scant foreign investment. Hundreds of thousand of people have been displaced from their homes, and nomads have been resettled into villages where they have no livelihood. Locals complain that China is primarily interested in extracting minerals to keep the factories back east running.”

Robert Barnett, a Tibet expert at Columbia, told the Washington Post, “It’s misleading to just ask if there’s been economic progress. Who benefits from it? What is the cost locally, culturally and politically?”

Nicholas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch told the Washington Post, “It’s not a people-centered modernization program, It’s a top down program that has mostly benefitted state enterprises and the party-controlled institutions.

One Uighur farmer told the Washington Post: It’s a little better than years past. We can eat. We have clothes to wear.” Then added “It’s more convenient for the Han to do business with one another.” An Uighur in the oil boom town of Kuche said, “Yes, there’s oil here but the money doesn’t reach ordinary people.”

Government-built yurts

Expanded Xinjiang Development

A central plank of the Hu Jintao’s "scientific theory of development" is specifically shrinking the gap between eastern and western China. In a major speech marking the opening of National People’s Congress in March 2010, Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao promised to expand growth and development in Xinjiang and Tibet. In May 2010, Chinese President Hu Jintao announced a $15-billion-a-year investment package at a special meeting of the Politburo on Xinjiang's economic future, partly to improve livelihoods and living conditions in the region and bolster confidence in the regional government, which was widely criticized by citizens after deadly ethnic rioting in the summer of 2009. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times May 28, 2010]

The announcement by the new Communist Party secretary of Xinjiang, Zhang Chunxian, 57, came on the heels of the national planning session. Zhang said the regional government would focus on developing the relatively poor areas of Uighur-dominated south Xinjiang.

Among the programs that ave been suggested are ones that promote bilingual education in all schools by 2015, especially in southern Xinjiang, so that all students can speak fluent Mandarin by 2020. Another was to move 700,000 urban families to safer and earthquake-resistant houses by 2015 and force 100,000 nomads to settle down.

The economic policies announced by the central government last week include overhauling tax policies in Xinjiang, encouraging foreign and commercial banks to open branches there, releasing more land for construction, and easing market access for some industries. The goal is to create a moderately well-off society in the region by 2020, Chinese leaders say.

The massive economic support package is significant, wrote Alistair Thornton, an analyst with IHS Global Insight, an international economic analysis group. However, Thornton said, whether breakneck economic development can placate Uighur grievances is uncertain.

In August 2011 the China Daily reported that 31 large state-owned enterprises plan to pour 991.6 billion yuan ($155 billion) into Xinjiang from 2011 to 2015. It said the investment will boost the region's infrastructure and transform it into a major production base for petroleum and energy-related industries.

Image Sources: Mongabey; Louis Perrochon

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2015