XINJIANG SEPARATISM AND HUMAN RIGHTS

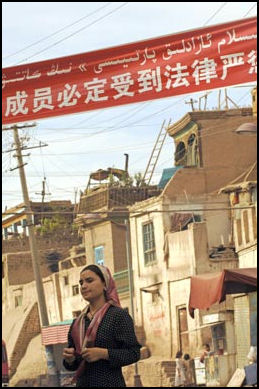

Signs warns of punishment

for being a member of

Muslim separtist group Many of the Muslims in western China want their own independent state similar to what Muslims in the former Soviet Republics now have. Some activists want Xinjiang to become an independent state called East Turkestan. According to some surveys 60 percent of Uighurs favor independence.

Muslims in Xinjiang don’t like the name Xinjiang (meaning “new territories” or “newly conquered territories”) because of the tacit connection to China. They prefer East Turkestan. On the that term Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist and blogger, said, "This phrase “East Turkestan” is something invented by Europeans and not something that Uyghurs themselves came up with. However, it has been built up by the Turks and forcibly thrust upon us. We Uyghurs have no concept of “East Turkestan.” From historic times to the presnt, Uyghurs have called Xinjiang “Land of the Uyghurs.” No one has ever called it “Land of the Turks,” much less “Eastern Land of the Turks.''

In many ways the Muslims seem less likely to go along with Beijing than Tibetans. Kashgar and Khotan — Uighur dominated towns — are regarded as the hotheads of East Turkestan nationalism. In Khotan and nearby towns there increasing signs of Islamism. Many Uighur women wear head scarves and when they get married they wear veils that leave only their eyes visible.

Many see the Xinjiang situation as more complicated and potentially dangerous than Tibet because Xinjiang and the Uighurs don’t have a strong leader like the Dalai Lama that can speak for a unified group and calm things down if they get out of hand. Instead resistance is fragmented.

See Separate Articles: Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com; UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG EARLY HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China

Websites and Sources: Xinjiang Wikipedia Article Wikipedia Xinjiang Photos Synaptic Synaptic ; Maps of Xinjiang: chinamaps.org Uyghur Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Uyghur Photo site uyghur.50megs.com ; Uyghur News uyghurnews.com ; Uyghur Photos smugmug.com ;Islam.net Islam.net ; Uyghur Human Rights Groups ; World Uyghur Congress uyghurcongress.org ; Uyghur American Association uyghuramerican.org ; Uyghur Human Rights Project uhrp.org ; Uyghur Language Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Claude Pickens Collection harvard.edu/libraries ; Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Xinjiang History Book on the Great Game: “The Dust of Empire: The Race for Mastery in the Asian Heartland” by Karl E. Meyer (Century Foundation/Public Affairs, 2003). Uyghur and Xinjiang Experts: Dru Gladney of Pomona College; Nicolas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch; and James Miflor, a professor at Georgetown University. Henryk Szadziewski is the manager of the Uyghur Human Rights Project (www.uhrp.org). He lived in the People's Republic of China for five years, including a three-year period in Uyghur-populated regions. Henryk Szadziewski studied modern Chinese and Mongolian at the University of Leeds, and completed a master's degree at the University of Wales, where he specialized in Uyghur economic, social and cultural rights. Tourist Office: Xinjiang Tourism Administration, 16 South Hetan Rd, 830002 Urumqi, Xinjiang China, tel. (0)- 991-282-7912, fax: (0)- 991-282-4449

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Xinjiang: China's Central Asia” by Jeremy Tredinnick Amazon.com; “Xinjiang and the Modern Chinese State” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com “Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland” by S. Frederick Starr Amazon.com; “Securing China's Northwest Frontier” by David Tobin” Amazon.com

Separatist Groups in Xinjiang

Isa Yusuf Alptekin, the exiled head of the Islamic Republic of East Turkestan, who died in 1995 at the of 94.

The East Turkestan Islamic Movement was founded in the 1930s and became radicalized in the 1990s. It has been blamed for bus bombings and assassinations.

The United National Revolutionary Front (UNRF) is an Uighur separatist group with exiled leaders based in Kazakstan. The Eastern Turkestan National Freedom Center was founded by Anwar Ysuf, in Washington in 1995.

These groups say they are fighting for basic human rights for the Muslim peoples of Xinjiang. In some cases they call for an independent East Turkestan state. Most denounce terrorism and have no connections with Al-Qaeda or Osama bin Laden. They view themselves as nationalist movements rather than Islamic ones. Uighurs and other Muslim groups in China have traditionally not been very religious.

Global fears about Islamic radicalism have prevented Uighurs from attracted the same kind of international support enjoyed by Tibetans. Uighurs also lack of a charismatic figurehead like the Dalai Lama to make their case and lead their movement. Human rights groups have accused Beijing of overstating the threat in Xinjiang, and using it as an excuse t crack down on Uighurs,

Radical groups don’t have a lot of support among ordinary Uighurs. A reporter for a newspaper in Hotan told the Yomiuri Shimbun, “The radical independence movement hasn’t been able to win the support of local residents. The only thing they can do is cause a bit of trouble in local areas. But authorities are now alerted to trouble that may occur." A 50-year-old Uighur man said, “I think our situation has improved. I’m not happy with the rule of the Han, but I don’t think the situation is that bad that we need independence.”

See Terrorism and Xinjiang

History of the Uighur Separatist Movement

Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist and blogger, told Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan: “In the 1950s, even though Mao Zedong criticized “great Han chauvinism” in Xinjiang, contemporary ethnic policies in Xinjiang never led to a rupture. Ethnic relations in Xinjiang really became more tense over the past 20 years or so. After taking office, Party Secretary Wang Lequan adopted a high-handed posture that would not allow for any ethnic sentiment among minority populations. For example, if a ethnic cadre were to express the slightest complaint during a meeting, he would definitely not be promoted and might even be sacked. [Wang] overemphasized and exacerbated the anti-separatist issue. In fact, border provinces in any country that have cultural, linguistic, or ethnic ties with foreign countries are bound to have such tendencies. The current anti-separatist struggle in Xinjiang is not simply something [being carried out] by law enforcement agencies but has become something [carried out] in the whole society.” [Source: Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan interview of Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist, blogger, and AIDS activist , siweiluozi.blogspot.com ]

“In fact, looking historically, the Uyghur people transformed early on from a desert-based [nomadic] people to an agricultural society and developed an extremely exquisite civilization. The nature of this people has become such that we don't spread or seek conflict. Even during its strongest point, this society was never expansionary. When the Khitan came, Uyghurs quickly surrendered. When the Mongols came, the Uyghurs basically surrendered without a fight. Historically speaking, Uyghurs don't like to fight and have no foundation for independence.

“At the time of the Silk Road, Uyghurs had opportunities to travel about in neighboring countries and their thinking was more open. Later, when maritime navigation became dominant, Uyghurs found themselves isolated and closed-off. In such a backwards circumstance, it's easy to think that “monks from outside can really chant the scripture” [i.e., outsiders have the answers]. It's just as when China first opened up, all sorts of ideas flowed in, both good and bad, and it wasn't clear which were good and which were bad. Moreover, over the past several decades local Uyghur elites suffered under the repression of the Communist Party's leftist policies and there were no opportunities to develop thought. The moment a few people shout “East Turkestan,” many among our people have no idea what to think.”

Interest in the Uighur Separatist Movement

Even the most optimistic Uyghur nationalists admit that their movement lacks two fundamental things - clear leadership, and international sympathy.

Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist and blogger, told Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan: “I don't think the main problem for Xinjiang is ethnic separatism. The key problem for Xinjiang is still economic development. Actually, so-called ethnic conflict is really conflict over interests. Last year during the “two meetings,” I watched video of President Hu Jintao's meeting with the Xinjiang delegation many times. President Hu said that Xinjiang should emphasize development and only at the end did he say anything about stability. Subsequently, I decided to write a series of articles clarifying my views on this.

My father took part in the “Revolution of the Three Districts” [in which ethnic partisans revolted against Chinese rule in 1944 and established the second East Turkestan Republic] as a soldier. Logically, he should be a classic example of someone with thoughts of independence, but as far as I know not even someone like him is pro-independence — much less so someone like me. [Source: Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan interview of Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist, blogger, and AIDS activist , siweiluozi.blogspot.com ]

China and Separatist Movements in Xinjiang

Beijing refers to Muslim and Tibetan separatists as "splitists." In 1996, Beijing ordered police to crack down hard on activists who oppose Communist rule. They cracked particularly hard on Xinjiang and Tibet because they were sources of the “three evils” of separatism, terrorism and religious extremism

Human rights groups say that in many ways Xinjiang is more tightly controlled than Tibet. One Communist official in Xinjiang told Reuters: ‘some people have used the cloak of religion to trick people. If you see through their acts you can see they want to split the motherland.”

The Chinese authorities do not make a distinction between separatist and terrorists. They lump Uighur activists engaged in rather mild political activity together with bonafide terrorists. According to Amnesty International, ‘separatism in fact covers a broad range of activities, most of which amount to no more than peaceful opposition or dissent. Preaching or teaching Islam outside government controls is also considered subversive.”

Nicholas Bequelin, a Hong Kong-bases researcher for Human Rights Watch, told Reuters, “the policies are actually widening the gap between Uighurs and the rest of the population. People build up barriers to protect their ethnic identity from the attempt by the state to remodel it.”

Political Violence in Xinjiang

There has been rioting, bombings and several assassination of pro-Chinese figures in Xinjiang. Local Islamic leaders have been assassinated for supporting Beijing's policies. Uighur Muslim radicals have been blamed for carrying out bomb attacks.

It is difficult for Western journalist to get accurate information about what is going on in Xinjiang. Information leaking from the trouble areas is minimal and the Chinese government does grant foreign reporters access to these areas.

In the 1980s students protested their treatment by police. Muslim uprisings — which the Communists called "racial incidents" — in and around the city of Kasghar in the 1980s left maybe a hundred dead.

Political Violence in Xinjiang in the 1990s

In 1990 a disturbance over birth limits south of Kashgar ended with around 50 dead Uighurs and Kyrgyz. The Chinese government described teh incident as a "counter-revolutionary rebellion." The Chinese government sealed off Kashgar and closed the border between Pakistan and China. Bombs reportedly set off by Muslim separatists exploded in Urumqi in 1992 and Kashgar in 1993.

In the summer of 1995, Muslims rioted in Hotan, where a popular imam was arrested for "fomenting dissent" A dozen of people were injured. In March, 1996, a pro-Chinese religious leader was assassinated. Around the same time there were attacks on Chinese officials and their relatives.

In the mid 1990s, 500 Uighurs demonstrated in Urumqi after the death of a Uighur student in a Chinese-run clinic. The student reportedly entered the clinic and was told that even though she had health insurance she wouldn't be treated until she coughed up a bribe of $120. She died when her pneumonia turned into meningitis.

Muslim separatist have reportedly bombed military vehicles in Urumqi, set off more than 50 explosions on the Xinjiang railroad network and stole important copies of the Koran from the Xinjiang Islamic Studies Center. Exiles also claim that 450 Chinese troops have been were killed by Muslim "freedom fighters" around Urumqi and 20 troops have been killed in Karamay and Turfan.

In 1999, according to the Taipei Times, separatist attacked a PLA missile base, killing 21 soldiers and destroying 18 vehicles.

Riot in Xinjiang in 1997

In the spring of 1997 rioting broke out in western Xinjiang in the town of Gulja (known as Yining in Chinese, about 250 miles west of Urumqi near the border of Kazakstan). About 1,000 Muslim separatists and their sympathizers battled police, destroyed shops and burned cars. More than 10 people were killed, 100 were injured and 50 were arrested. The bodies of many of those who died were burned. According to some estimates as many as 80 people were killed.

The riot reportedly began when police burst into a private home that was holding a prayer meeting to mark the end of Ramadan, the Muslim holy month of fasting, and tried to arrest an Uighur criminal who resisted arrest and attracted a large crowd that began rioting. The arresting policeman was reportedly stabbed to death and hundreds of paramilitary police had to be called in to restore order. One eyewitness said, "Police opened fire on a crowd. A hundred were killed. The same day 30 people were shot in another place without a trial, without an investigation.”

In 2000, Uighur militants and police clashed in the Xinjiang city of Aksu.

Unrest in Xinjiang in 2008

In March 2008, Chinese authorities said they had uncovered evidence that the group that was raided the previous January was planning a terrorist strike during the Olympics. A high-level official said, “Obviously the gang had planned an attack targeting the Olympics” but gave no specific evidence. In April, Chinese authorities said they detained 45 East Turkestan “terrorists” and closed down a ring in Xinjiang that was planning to carry out suicide bombings and abduct Olympics athletes. Uighur activists said the charges were fabricated.

In March 2008, a plane bound for Beijing from Urumqi was diverted to Lanzhou after suspicious liquids were found aboard the plane. Two people were reportedly involved in what was called a hijacking, terrorist and sabotage. attempt. A 19-year-old Uighur woman, according to government sources, confessed to attempting to hijack the plane. Officials said she was part of terrorist group that wants to establish an independent state of East Turkestan. The woman is said to have smuggled three containers with gasoline onto the plane and took them into a bathroom where she was apprehended by the crew.

In late March 2008, about a week after the Tibetan riots in Lhasa, protests occurred in Xinjiang in Hotan, about 625 miles southwest of Urumqi, after a prominent jade trader died in police custody. Hundreds marched through a weekly market. According to Free Asia, the protesters demanded an end to a ban of head scarves,, more autonomy for Uighur-populated regions and the release of political prisoners. There seemed to be no connection between these protests and those in Tibet. Some think that Hizb ut-Tahrir was responsible for organizing the protests in Khotan.

According to some accounts more than 1,000 women, demanding the lifting of the ban on wearing head scarves, were involved in the protest in Khotan. Other reports said there were about 500 demonstrators demanding Uighur independence. According to the Hoton local government website: “A small number of elements tried to incite splittism, create disturbances in the marketplace and even trick the masses into an uprising.”

The protest was peaceful and isolated but touched off fears that unrest that began in Tibet was spreading beyond Tibet. The Chinese government blamed the protests on ethic separatists. There were reports that a group of people dressed in black hijab began handing out leaflets calling for the independence of the region. These people were quickly rounded up. More than 500 people in total were detained.

Hotan (Khotan) is regarded as a hot bed of Muslim fundamentalism and Uighur separatism. After the protest, security was beefed up in Hotan out of concern that a uprising like the one in Tibet could break out there. Under near martial-law-like conditions, security personnel did house-to-house searched and asked people on the streets for their identity cards

Chinese Crackdowns and Discrimination in Xinjiang

A Chinese official told the Los Angeles Times, “In Xinjiang, the separatists, religious extremists and violent terrorists are all around us, In China, endangering national security is the No. 1 crime. We have to crackdown on it severely.” September 11th gave Beijing more leverage as the accused Xinjiang separatist groups of having ties with Al-Qaida.

Security cameras are becoming a common sights in Uighur housing projects in Kashgar and Urumqi. “Mashrap”, traditional all-male gathering, are closely regulated by the government. Uighurs are often barred from hotels and Internet cafes because they are assumed to be terrorists or criminals. They are watched suspiciously by Han security guards when they enter shops.

See Repression of Islam

Beijing’s grip on Xinjiang has been described as Soviet-like. The Chinese government has restricted religious freedom, closed local publishing houses and given special powers to the special "rapid-deployment force." Soldiers and police have increased their presence. Paramilitary guards with semi-automatic weapons stand at entrances to government buildings in Urumqi. Authorities have raided street stalls and whole markets that sold Osama bin Laden merchandise.

The Chinese government has used terrorism as an excuse to crack down on any kind of activity they view as a threat or don’t like. Uighurs have been arrested for showing signs of dissent, meeting with foreigners, and fasting in Ramadan. Among those that have been arrested are travel agency workers that met with foreign tourists after work. As a carrot, Beijing has offered job opportunities as a way blunting separatist activities.

Strike Hard — an anti-crime campaign intended to fight organized crime, drugs and pornography — has become a cover to crackdown on Uighurs. Yu Jianrong of the Institute of Rural Development told the Washington Post: “If you want a peaceful life, you must have strong and forceful measures. If the government wants to keep Xinjiang inside Chinese territory. They must take measures to crack down on separatists without any softness.”

Few Uighurs are willing to identify themselves by name when they talk to foreign reporters out of fear of drawing the attention of police and authorities to themselves. Those that do talk are very careful about what they say. One told the New York Times, “There are some words we feel in our hearts, but we cannot say.”

After the 1997 riot, Chinese troops quickly sealed off the town, closing roads and the airport. Prominent Uighurs were arrested Tear gas and water canons were used to break up demonstrations. A curfew was imposed and 1,000 Muslims were taken away in buses commandeered from local bus companies.

After the Kuqa shootout in 2001, sweeps of Uighur neighborhoods were conducted. A government spokesman said, “A lot of people were involved. We caught most of them, executed some of the them.” It is widely believed that many innocent people were arrested, and even executed.

Tearing Down the Old City of Kashar

Tearing Down the Old City of Kashar, See Separate Article

Arrests and Executions in Xinjiang

By some estimates 1,000 people have been killed and 10,000 have arrested in crackdowns on suspected separatists and terrorists. According to exiled separatists in Kazakstan, 57,000 suspected pro-independence supporters, including academics and clerics, were arrest in 1996.

Accused terrorists are often executed. In 1997, 16 people were executed in Xinjiang for Muslim unrest. An additional 20 people wee executed in 1996 for the rolls in Yining riots and Urumqi bombings. According to Amnesty International, Xinjiang is only place where executions are carried out for political crimes. One Amnesty International listed 210 death sentences and 190 executions between 1997 and 2000. Most were Uighurs

In June 2005, 10 Uighur activists were arrested and charged with plotting independence and separatism

Beijing’s crackdown it seems have largely been successful. The bombings, protests and unrest that occurred in the 1990s now seem like events in the distant past. But some say resentment has only been driven underground. Dru Gladney, an expert of western China at Pomona Collage, told the Los Angeles Times, “They put out the fire. But the embers are smoldering. And unless they address hearts and minds, it will flare again.” One Uighur man in Khotan told Reuters, “Even for small things you hear about people being taken away. So any kind of bigger incident I don’t think could happen here.”

In November 2007, six Uighurs tied to Hizb ut-Tahrir were given prison sentences from death to life in prison on charges of ‘splittism and organizing and leading terrorist groups.” One of the men that was found guilty of “carrying out extremist religious activities and promoting “jihad,” was accused of establishing a terrorist training base and preparing to set up an Islamic caliphate.

Xinjiang and Human Rights

Uighur activist Rebiya Kadeer said, “Uighur men, women and children in East Turkestan continue to live under an extremely brutal form of repression. They live in constant fear that they will become victims of state violence.”

Human Rights Watch has accused the Chinese government of waging a “whole assault” against the Uighurs, using tactics such as vetting imam, closing mosques, detaining thousands of people and executions. There have been reports of Uighur women between the ages of 16 and 25 being forcibly “transferred” to coastal cities ro work as cheap labor.

Amnesty International has reported "gross violations" of human rights, including arbitrary detention and arrests, torture, deaths during detention, and executions for vague political crimes such as "disrupting social order." By some accounts several hundred

Tohti Tuniyaz, an Uighur doctorate student at Tokyo University, was arrested in 1997 for copying a list of historical documents at a public records office for a book he was publishing and was sentenced to 11 years in prison. He maintained his innocence and was still in jail as of 2009.

Uighur dissidents are often given long sentences. Local people say more than 300 Uighur civil servants have been jailed for their beliefs and some have been beaten to death in prison.

Minorities in Xinjiang are reluctant to talk about their problems or speak openly out of reprisals from the Chinese government. A taxi driver in Aksu told the Washington Post, “The police are everywhere, and they pay Uighurs to spy in every neighborhoods and every mosque. Sometimes, people just disappear.”

In May 2007, Beijing banned Uighur people from traveling to foreign countries. A number of Uighurs who fled to Central Asian countries such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have been extradited to China and imprisoned.

German-based World Uighur Congress.

China, Central Asia and Separatist Movements in Xinjiang

Beijing is worried about support given to these separatist groups given by China's central Asian neighbors, particularly Afghanistan and Kazakstan.

Beijing has forged closer ties with Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Kazakstan partly to gain their support against Uighur separatists. These countries now regularly extradite alleged separatists, some of whom have are believed to have been executed. In return Chins has given these countries military aid and invested in their economies.

One Western diplomat told AFP, "Beijing will never give up its strategic link to Central Asia and Pakistan, but certain elements of the ethnic Uighurs population will attack their Chinese rulers whenever they have a chance."

Kazakhstan has cooperated with China by repatriating Uighur that Beijing has accused of being terrorists.

In April 2007, China jailed Uighur-Canadian Huseyib Celil to life in prison for “terrorist activities and plotting to split the country” and warned Canada not to get involved in the case. Celil was described as prominent member of pro-East Turkestan “terrorist organization.” Celil fled China in the mid-1990s and was granted refugee status in Canada where he became a citizen in 2005. In March 2006, he was detained in Uzbekistan while visiting relatives and sent to China in June of that year

Lack of Support for the Uighurs in Central Asia and the Muslim World

In contrast, most Muslim countries have not seen much benefit in riling China over an issue that arouses little international attention compared with human-rights abuses in neighboring Tibet or the situation in Israel and Palestine. . [Source: The Economist, July 16, 2009]

“The reaction to Xinjiang’s unrest among Central Asian countries which are home to Turkic peoples has also been muted. The immediate concern for the Kazakh and Kyrgyz governments has been the safe return from Xinjiang of their citizens, many of them shuttle traders. Both countries have sizeable Uighur populations — 50,000 in Kyrgyzstan; 300,000 in Kazakhstan (including the prime minister, Karim Massimov). There are also an estimated 1m ethnic Kazakhs in Xinjiang, who complain that they face the same sort of pressure on their culture and traditions as the Uighur.”

“Mindful of China’s proximity, and of the dangers of being sucked into further unrest, the stans have taken a dim view of Uighur separatism. Kazakhstan, for example, has sent a few separatists wanted by China back to Xinjiang. The rewards of Central Asia’s co-operation are obvious. In April China agreed to lend Kazakhstan $10 billion in a loan-for-oil deal. In June it offered another $10 billion in credit to members of the Shanghai Co-operation Organization — which links four Central Asian states with Russia and China — to shore up their struggling economies. As Turkey will find, there may be little to be gained by supporting the hapless Uighurs, except, perhaps, secret sympathy for its stance beyond China.”

Turkish Support of the Uighurs

The Economist reported: “Turkish prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, suggested that the recent violence in Xinjiang’s capital Urumqi involved genocide. Turkey’s trade minister Nihat Ergun hinted strongly that Turkish consumers should boycott Chinese goods (though his ministry quickly said that this was a personal view). Mr Erdogan proposed a discussion of the rioting in the UN Security Council. This is a non-starter given China’s power of veto, but the very idea infuriated China.” [Source: The Economist, July 16, 2009]

“The plight of Turkey’s Kurdish minority has never been of compelling interest to ordinary Chinese people. But Erdogan expressed his views internet forums in China have been clamoring their support for Kurdish separatists.”

Turkey’s cultural, religious and ethnic links with Xinjiang make it difficult for leaders there to keep quiet. Turkey has long been a haven for disaffected Uighurs, including Isa Yusuf Alptekin, the pre-eminent leader of Uighur nationalism until his death in 1995. To China’s fury, Mr Erdogan, when mayor of Istanbul, named part of a central park after Alptekin in the 1990s. As prime minister he has offered a visa to Rebiya Kadeer, a Uighur exile accused by China of fomenting Xinjiang’s violence.

In recent years Turkey’s support for the Uighur cause had been dampened by China’s rapid economic rise and its growing international clout. In 2003 Mr Erdogan visited China with a large delegation to mend relations. A few days before rioting erupted in Urumqi, Turkey’s President Abdullah Gul also paid a visit, saying afterwards that relations had turned a new page.

U.S. College Professors Blacklisted in China for Views on Xinjiang

Daniel Golden and Oliver Staley wrote in Bloomberg, “They call themselves the “Xinjiang 13.” They have been denied permission to enter China, prohibited from flying on a Chinese airline and pressured to adopt China- friendly views. To return to China, two wrote statements disavowing support for the independence movement in Xinjiang province. They aren’t exiled Chinese dissidents. They are American scholars from universities, such as Georgetown and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who have suffered a backlash from China unprecedented in academia since diplomatic relations resumed in 1979. Their offense was co-writing “Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland,” a 484-page paperback published in 2004. [Source: Daniel Golden and Oliver Staley, Bloomberg August 10, 2011]

“I wound up doing the stupidest thing, bringing all of the experts in the field into one room and having the Chinese take us all out,” Justin Rudelson, former senior lecturer at Dartmouth College, who helped enlist contributors to the book and co-wrote one chapter, told Bloomberg. The sanctions, which the scholars say were imposed by China’s security services, have hampered careers, personal relationships and American understanding of Xinjiang.

Colleges employing the Xinjiang scholars took no collective action, and most were reluctant to press Chinese authorities about individual cases. Dartmouth almost fired Rudelson because he couldn’t go to China, he and Rieser said. “As a group, most of us have been very disappointed in the colleges and universities lack of sympathy and support,” said Dru Gladney, an anthropology professor at Pomona College in Claremont, California, who described himself and his American co-authors as the “Xinjiang 13.” Colleges are ‘so eager to jump on the China bandwagon, they put financial interests ahead of academic freedom.”

Gladney’s invitation to speak at a conference in Tianjin, China in April was rescinded after a Communist party official vetoed his participation, he said. A professor of Chinese history at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan, Linda Benson contributed the chapter on minority education in Xinjiang. After writing a 2008 book about British women missionaries to China’s Muslim regions, she was invited to a May 2010 Christian-history conference in Gansu Province in northwest China. She was denied a visa. The chapter written by Gardner Bovingdon, an associate professor at Indiana University in Bloomington, compared Uighur and official Chinese histories of Xinjiang. When Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s board met in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital, in 2006, it asked Bovingdon to speak. He couldn’t get a visa.

Disputed Book on Xinjiang

Daniel Golden and Oliver Staley wrote in Bloomberg, Xinjiang had attracted little academic attention until the New York-based Henry Luce Foundation approved a $330,000 grant to the School of Advanced International Studies, or SAIS, at Johns Hopkins in 2000, said former foundation Vice President Terry Lautz. “We expected that the project would fill a gap,” said Lautz, who described the book as “very scholarly, very thorough, very carefully written and researched.” [Source: Daniel Golden and Oliver Staley, Bloomberg August 10, 2011]

S. Frederick Starr, the volume’s editor, chairs the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute at SAIS, which is based in Washington. He recruited the book’s 15 co-authors: 13 Americans, one Israeli, and one Uighur. Contributors were paid $3,000 apiece, Rudelson said. Each tackled a different aspect of Xinjiang history and society, from the province’s economy, ecology, education and public health to Islamic identity and the Chinese military presence.

“I remember people saying at the beginning, “Do you think China will ban us?” Rudelson said. Starr decided against having Chinese co-authors because he didn’t want to cause them trouble with their government. He also informed the Chinese embassy at the outset about the book, giving assurances that the tone would be objective. In response, the embassy ‘sent senior scholars who were obviously on a fact-finding mission,” Starr said. “We sat and had very pleasant conversations.”

Then the Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences prepared a translation of the Johns Hopkins book for Chinese officials and scholars. In an introduction to the Chinese translation, Pan Zhiping, a researcher at the academy, portrayed “Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland” as a U.S. government mouthpiece. Featuring “a hodgepodge of scholars, scholars in preparation, phony scholars, and shameless fabricators of political rumor,” the book by the Xinjiang 13 “provides a theoretical basis for” America “one day taking action to dismember China and separate Xinjiang,” Pan wrote.

Sichuan Airlines, a government-owned regional airline, put six of the authors on a no-fly list in 2006, according to a document provided to Bloomberg News. In the “urgent” communication, the airline’s Beijing management office instructed sales representatives to inspect the scholars’ documents and prevent them from boarding. As the co-authors began applying to return to China, their visas were denied without explanation.

“If I had pulled together a book like this that got an entire generation of scholars on a certain topic banned from the country they research, I’d like to think I would step forward to organize a coordinated response,” said James Millward, a professor in Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service who co-wrote two chapters on Xinjiang’s political history. Starr “just wanted nothing to do with it.” The Luce Foundation’s Lautz said he urged Starr to “at least raise the issuewith China. “That didn’t really happen,” Lautz said.

Image Sources: Mongabey,

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Thomas B. Allen, National Geographic, March 1996

Last Updated November 2011