XINJIANG

Xinjiang XINJIANG is China's westernmost region and largest political entity. Larger than Alaska and occupying roughly one sixth of China's total area, it is covered mostly by vast, inhospitable desert punctuated here and there by bazaar towns, ancient ruins, oil camps, and Chinese cities with discos and shopping malls, with massive snow-capped mountains in the west and south. Xinjiang (pronounced SHEEN-jee-hang) means "new frontier." The two Chinese characters that form the word are pictograms that represent "bow," "land," "field" and "border."

Like Tibet and Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang is an autonomous region, not a province. Officially known as Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region, it was set up as an autonomous region for Uyghurs, the same way Tibet was set up as an autonomous regions for Tibetans. Like Tibetans, Ughyurs feel their region is autonomous in name only. Their religion and culture are suppressed and their homeland is being overrun with Han Chinese. Many Uygurs would like Xinjiang to become an independent country, or even join Kyrgyzstan, a former Soviet Republic that lies along its western border.

Despite its generally inhospitable landscapes, Xinjiang also contains some of the most incredible sites in China: 26,000-foot-high mountains with glaciers, evergreen forests and Alpine meadows, Silk Road oases with bazaars and folk fairs, and ruined cities inhabited by lost Christian tribes and people with Caucasian features. Even the Chinese regard Xinjiang as a mysterious place. The lifestyle of many of its people has changed little since the 13th century when Marco Polo visited the region and nomads lived in the mountains and settled people lived around the oases, where the Silk Road caravans stopped.

Xinjiang ( pinyin: Xīnjiāng; Wade–Giles: Hsin-chiang; postal map spelling: Sinkiang) has abundant oil reserves and is China's largest natural gas-producing region. It is home to 13 major ethnic groups and borders eight countries, more than any other Chinese region or province. Xinjiang has been called China's Wild West. Many Han Chinese have gone there in hopes of striking it rich in the region's oil field or trade centers, with local Muslim minorities being pushed aside like American Indians. Xinjiang is rich in minerals and has large oil deposits and the largest natural gas reserves in China. It is the home of China’s main nuclear testing site. It has traditionally served as a defensive buffer against possible attacks from the West, which is one reason why the Chinese don't want to lose control over it.

Han Chinese now account for at least 40 percent of Xinjiang’s 25 million people. Many experts feel there are far more Han Chinese than are reflected din the statistics. Northern Xinjiang cities like Urumqi and Turpan can be reached by train. The Silk Road city of Kashgar in the south can be reached from Pakistan via the Karakorum Highway or by a new train that began service in 2004.

See Separate Articles: Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com; UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG EARLY HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China

Websites and Sources: Xinjiang Wikipedia Article Wikipedia Xinjiang Photos Synaptic Synaptic ; Maps of Xinjiang: chinamaps.org Uyghur Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Uyghur Photo site uyghur.50megs.com ; Uyghur News uyghurnews.com ; Uyghur Photos smugmug.com ;Islam.net Islam.net ; Uyghur Human Rights Groups ; World Uyghur Congress uyghurcongress.org ; Uyghur American Association uyghuramerican.org ; Uyghur Human Rights Project uhrp.org ; Uyghur Language Uyghur Written Language omniglot.com ; Xinjiang Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Claude Pickens Collection harvard.edu/libraries ; Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Uyghur and Xinjiang Experts: Dru Gladney of Pomona College; Nicolas Bequelin of Human Rights Watch; and James Miflor, a professor at Georgetown University. Henryk Szadziewski is the manager of the Uyghur Human Rights Project (www.uhrp.org). He lived in the People's Republic of China for five years, including a three-year period in Uyghur-populated regions. Henryk Szadziewski studied modern Chinese and Mongolian at the University of Leeds, and completed a master's degree at the University of Wales, where he specialized in Uyghur economic, social and cultural rights. Tourist Office: Xinjiang Tourism Administration, 16 South Hetan Rd, 830002 Urumqi, Xinjiang China, tel. (0)- 991-282-7912, fax: (0)- 991-282-4449

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Xinjiang: China's Central Asia” by Jeremy Tredinnick Amazon.com; “Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang” by Christian Tyler Amazon.com; “Xinjiang and the Modern Chinese State” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com “The Backstreets: A Novel from Xinjiang” by Perhat Tursun and Darren Byler Amazon.com; “Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland” by S. Frederick Starr Amazon.com; Travel: “Xinjiang: A Traveler’s Guide to Far West China” by Josh Summers Amazon.com; “The Road to Miran: Travels in the Forbidden Zone of Xinjiang” by Christa Paula Amazon.com; History: “Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang” by James Millward Amazon.com; “The Cultures of Ancient Xinjiang, Western China: Crossroads of the Silk Roads” by Alison Betts, Marika Vicziany, et al. Amazon.com; “The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West” by Victor H. Mair and J. P. Mallory Amazon.com; “The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia” by Peter Hopkirk Amazon.com; “Securing China's Northwest Frontier” by David Tobin” Amazon.com

Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region

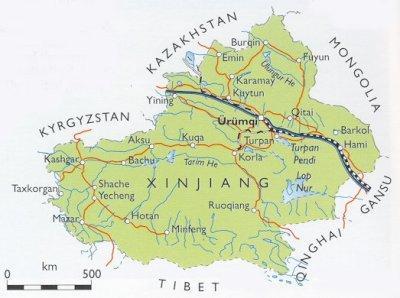

Xinjiang map Xinjiang is officially known as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). It is not province but is an autonomous region presumptively set up of the Uyghur people. XUAR is the largest province-level division in China but one of the least densely populated. It is larger than Tibet and is roughly the same size as Alaska.

Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region covers 1,664,897 square kilometers (642,820 square miles)and has a population density of only 16 people per square kilometer. According to the 2020 Chinese census the population was around 25.8 million. About 49 percent of the population lives in rural areas. Urumqi is the capital and largest city, with about 3.5 million people. Ethnic: composition Uyghur: 45.84 percent; Han Chinese: 40.48 percent; Kazakh: 6.50 percent; Hui: 4.51 percent; Other: 2.67 percent. Languages and dialects: Uyghur (official); Mandarin (official); Kazakh: Kyrgyz: Oirat; Mongolian; 43 other languages. Religion in Xinjiang: Muslim 58 percent; Chinese religions, Buddhism or not religious: 41 percent; Christianity; one percent.

Like Chinese provinces, an autonomous region has its own local government, but an autonomous region — theoretically at least — has more legislative rights. An autonomous region is the highest level of minority autonomous entity in China. They have a comparably higher population — but not necessarily a majority — of the minority ethnic group in their name. Some of them have more Han Chinese than the named ethnic group. There are five province-level autonomous regions in China: 1) Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region for the Zhuang people, who make up 32 percent of the population; 2) Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Nei Mongol Autonomous Region) for Mongols, who make up only about 17 percent of the population; 3) Tibet Autonomous Region Autonomous Region (Xizang Autonomous Region) for Tibetans, who make up 90 percent of the population; 4) Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, for Uyghurs, who make up 45.6 percent of the population; and 5) Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, for the Hui, who make up 36 percent of the population. [Source: Wikipedia]

Geography of Xinjiang

Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region(XUAR) covers 1,664,897 square kilometers (642,820 square miles) and is by far the biggest of China’s regions and provinces. Accounting for more than one sixth of China's total territory and a quarter of its boundary length, it is more than twice the size of Texas and nearly as big as Alaska. Its mountains and deserts contain huge deposits of oil, natural gas, coal, gold and other minerals, but the province has just 25 million people.

Xinjiang occupies much of the sparsely-populated northwest part of China. It embraces two large basins: the Junggar (Dzungarian, Zhungarian Jungarian) Basin and Tarim basins. The latter is the largest inland basin in the world. Junggar basin lies in a region surrounded by tree-covered snow-capped mountains that are reminiscent of the Alps. Many Kazakhs and Torgut Mongols live there. Deserts include: Dzoosotoyn Elisen Desert, Kumtag Desert. Taklamakan Desert; Major cities are: Urumqi, Turpan, Kashgar, Karamay, Yining, Shihezi, Hotan, Atux, Aksu, Korla

XUAR is bounded by the Altay (Altai) Mountains in the north, the Pamirs in the southwest, and the Karakoram Mountains, Altun Mountains and Kunlun Mountains in the south. The Tian Shan Mountains divide Xinjiang into northern and southern parts — the Junggar Basin in the north, and the Tarim Basin in the south — with very different climates and landscapes. Much of the Tarim Basin is dominated by the Taklamakan Desert. Wheat, maize and paddy rice are the region's main grain crops, and cotton is a major cash crop. Since the 1950s, cotton has been grown in the Manas River valley north of 40 degrees latitude. The Tian Shan Mountains are rich in coal and iron, the Altay in gold, and the Kunlun in jade. The region also has big deposits of non-ferrous and rare metals and oil, and rich reserves of forests and land open to reclamation.

Xinjiang's vast expanse is mostly desert and grassland. Southern Xinjiang includes the Tarim Basin and the Taklamakan Desert, China's largest, while northern Xinjiang contains the Junggar Basin, where the Karamay Oilfields and the fertile Ili River valley are situated. The Turpan Basin, the hottest and lowest point in China, lies at the eastern end of the Tian Shan Mountains. The Tarim, Yarkant, Yurunkax and Qarran rivers irrigate land around the Tarim Basin, while the Ili, Irtish, Ulungur and Manas rivers flow through arable and pastoral areas in northern Xinjiang. Many of the rivers spill into lakes. The Lop Nur, Bosten (Bagrax), Uliungur and Ebinur lakes teem with fish.

Xinjiang’s highest point is K2 (8611 meters, 28,251 feet), the world's second highest mountain, on the border with Pakistan. Xinjiang has within its borders the point of land farthest from the sea, the so-called Eurasian pole of inaccessibility (46°16.8 N 86°40.2 E) in the Dzoosotoyn Elisen Desert, 1,645 miles (2,647 kilometers) from the nearest coastline (straight-line distance). The Tian Shan mountain range marks the Xinjiang-Kyrgyzstan border at the Torugart Pass (3752 meters). The Karakorum highway (KKH) links Islamabad, Pakistan with Kashgar over the Khunjerab Pass.

Xinjiang borders: 1) Gansu province to the east; 2) Qinghai Province to the southeast; 3) Tibet Autonomous Region to the south; 4) Jammu and Kashmir (India) Disputed and Gilgit-Baltistan (Pakistan) to the southwest; 5) Badakhshan Province, Afghanistan, Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province, Tajikistan, Osh, Naryn, and Issyk Kul Provinces, Kyrgyzstan and Almaty, East Kazakhstan Provinces, Kazakhstan to the west; 6) Altai Republic, Russia, to the north; and 7) Bayan-Ölgii, Khovd, Govi-Altai Provinces, Mongolia to the northeast.

Weather, Geology and Time in Xinjiang

Generally, Xinjiang has a semi-arid or desert climate The entire region is marked by great seasonal differences in temperature and cold winters. During the summer, the Turpan Depression usually records the hottest temperatures in China, with temperatures often exceeding 40 °C (104 °F). In the far north and the highest mountain elevations, and even the capital of Urumqi, temperatures regularly drop below −20 °C (−4 °F) in the winter.

Xinjiang's climate is dry and warm in the south, and cold in the north with plenty rainfall and snow. The Uyghurs farm areas around the Tarim Basin and the Gobi Desert. Xinjiang sometimes experiences fierce dust and sand storms. A boran is a fierce sandstorm wind. A bad one may halt bus and train transport, kill several people, thousand of farm animal and destroy tens of thousands of acres of farmland.

Geology: Most of Xinjiang is young geologically, having been formed from the collision of the Indian plate with the Eurasian plate, forming the Tian Shan, Kunlun Shan, and Pamir mountain ranges. Consequently, Xinjiang is a major earthquake zone. Older geological formations occur principally in the far north where the Junggar Block is geologically part of Kazakhstan, and in the east which is part of the North China Craton. Earthquakes : See Nature, Natural Disasters, Earthquakes

Time and Life in Xinjiang

Officially, Xinjiang is on the same time zone as the rest of China, Beijing Time (UTC+8). However, it is roughly two time zones west of the capital, some residents follow their own unofficial Xinjiang Time (UTC+6).The division follows ethnic lines, with Han tending to use Beijing Time and Uyghurs tending to use Xinjiang Time. This is seen by Beijing as a form of resistance to the central government. Regardless of the ethnicity of their proprietors, most businesses and schools open and close according to Xinjiang time, two hours later than elsewhere in of China.

Officially Xinjiang sets its clock to Beijing time which means that the sun rises at noon in Kasghar and foreigners who wake up at 8:00am find that everyone is asleep. Trains run on Beijing time but many buses schedules are set to Xinjiang time which is one hour behind Beijing time (2 hours in the summer because there is no daylight saving time in Xinjiang). Kashgar time is one hour behind Xinjiang time.

Not restricted by the "one couple, one child" birth control laws. Rural minority couples in western China are allowed to have three children and urban couples two. To have even more children some pastorialists in Xinjiang "parcel" out some of their children to relatives.

Entertainment in Xinjiang is provided by karaoke bars, street performing monkeys and mobile pool tables which are rolled from neighborhood to neighborhood for 20 cent games. There have traditionally been few refrigerators in Western China, one of the hottest regions in the world during the summer. Some household ice boxes are supplied by pond ice which has been chipped away during the winter and stored in felt- lined caves and pits and delivered door to door by donkey cart during the summer.

Xinjiang is a semi-autonomous territory and the Uyghurs have there own parliament in Urumchi. According to Xinjiang law the governor of the autonomous region of Xinjiang must be Uyghur. Some important Communist Party members are from minority groups but all of them have Han Chinese superiors. Minorities in Xinjiang are allowed to print newspapers and have radio and television broadcasts in their languages.

The Chinese military has conducted fairly sophisticated wars games and large military exercises in Xinjiang. Residents of Xinjiang launched China's first anti-nuclear protests. Lop Nor in Xinjiang is the nuclear testing site where China detonated its first nuclear weapons. Near Lop Nur there have been reports livestock and people suffering from radiation sickness. Many trees in the region have lost their leaves and bark. Residents complain of losing their hair and suffering from skin diseases. There have been increases in rates leukemia, throat cancer, premature births and deformed babies. Malan, a secret nuclear base, is only 10 kilometers from villages with ethnic Uyghurs and Mongols.

Organized crime is a problem in Xinjiang. In July 2008, five gang members were shot dead after one of them stabbed a police officer while resisting arrest. The gangsters reportedly entered a beauty parlor with knives.

Education in Xinjiang

People of Xinjiang have the right to use their native languages in schools. But in many cases this means the instruction is in Uyghur but the lessons are Chinese propaganda. Under portraits of Mao and Marx, children are encouraged to abandon Islam and are encouraged to eat during the Muslim fast of Ramadan.

Young people have a hard time getting into university because their Chinese language skills are not good enough. Special Mandarin-only schools have been set up for the best and brightest. A student at one such school in Urumqi told the Los Angeles Times, “Chinese is very difficult, but it's the language of the marketplace. I’ve studied for two years. Sometimes I forget some of my Uyghur.”

Many Uyghurs have welcomed programs to teach Mandarin side by side with Uyghur in their schools — with the understanding that Mandarin is useful in business and generally getting ahead — but have been hostile to the idea of Uyghur being phased out and replaced by Mandarin-only instruction.

Since 2000, most public schools have made Mandarins the primary language of instruction. The first to bear the brunt of the bilingual education policy were teachers who had previously taught in ethnic languages. Tens of thousands of teachers faced being laid off because their Chinese was not up to standard, and this led to unstable popular feelings among grassroots educators.

In Kashgar, a bilingual education program begun in local schools several years ago, for example, had been welcomed by Uyghurs who agreed that learning Mandarin Chinese would be good for business. But recently, some schools have started teaching just Mandarin, angering parents who want their children to also use their own language. [Source: Maureen Fan, Washington Post, March 24, 2009]

The Uyghur language has been phased out of higher education. Mobile primary schools are taken to the grassland in Xinjiang.

People of Xinjiang

Xinjiang has a population of roughly 25 million people and is inhabited by 13 of China's 55 official minorities. The population density is only 15 people per square kilometer and about 49 percent of the population lives in rural areas. Ethnic: composition Uyghur: 45.84 percent; Han Chinese: 40.48 percent; Kazakh: 6.50 percent; Hui: 4.51 percent; Other: 2.67 percent. Languages and dialects: Uyghur (official); Mandarin (official); Kazakh: Kyrgyz: Oirat; Mongolian; 43 other languages.Religion in Xinjiang: Muslim 58 percent; Chinese religions, Buddhism or not religious: 41 percent; Christianity; one percent. Only about 4.3 percent of Xinjiang's land area is fit for human habitation.

Xinjiang has a population of roughly 25 million people and is inhabited by 13 of China's 55 official minorities. The population density is only 15 people per square kilometer and about 49 percent of the population lives in rural areas. Ethnic: composition Uyghur: 45.84 percent; Han Chinese: 40.48 percent; Kazakh: 6.50 percent; Hui: 4.51 percent; Other: 2.67 percent. Languages and dialects: Uyghur (official); Mandarin (official); Kazakh: Kyrgyz: Oirat; Mongolian; 43 other languages.Religion in Xinjiang: Muslim 58 percent; Chinese religions, Buddhism or not religious: 41 percent; Christianity; one percent. Only about 4.3 percent of Xinjiang's land area is fit for human habitation.

The population of Xinjiang was 25,852,345 in 2020; 21,813,334 in 2010; 18,459,511 in 2000; 15,155,778 in 1990; 13,081,681 in 1982; 7,270,067 in 1964; 4,873,608 in 1954; 4,047,000 in 1947; 4,360,000 in 196-37; 2,552,000 in 1928; 2,098,000 in 1912. [Source: Wikipedia, China Census]

Most of ethnic groups in Xinjiang are of Turkic descent and around 14.5 million are Muslims. Turkic century groups include the Uyghurs Kyrgyz, Tajiks, Uzbeks and Kazakhs. Older English-language reference works often refer to the area as Chinese Turkestan. The Hui are Chinese Muslims. Some Tatars live in the Ili Valley west of Urumqi. Non-Muslims include Xibe, Manchu, Daur, and Russians. A large number of Mongolians live in the central region of Xinjiang. They have traditionally been Tibetan Buddhists. There are more than a dozen autonomous prefectures and counties for minorities are in Xinjiang.

Xinjiang is home to about 3.5 percent of China's population. In 1949, when the Communist Party swept to power in China, Han Chinese made up less than 10 percent of Xinjiang's population. At that time, roughly 80 percent of the people in Xinjiang were Uyghurs and 10 percent were other groups. By the late 1990s, 38 percent of Xinjiang's people were Han Chinese, 44 percent were Uyghurs and 18 percent were other. Today, Han Chinese comprise 40.5 percent and 46 percent are Uyghurs, with other, mainly Muslim ethnic groups, making up the remaining 15 percent of the province's population. Kazakhs made up about 9 percent of the population the 1940s and around 6.5 percent today.

The Uyghurs are the largest ethnic group in Xinjiang but they are now outnumbered by Han in the cities. Although Uyghur numbers have been diluted in northern Xinjiang by Han Chinese settlers and are now outnumbered there, the Uyghurs are still the majority in southern Xinjiang. Between 250,000 and 300,000 Han Chinese enter Xinjiang each year. One Urumqi resident told National Geographic, "Every day the trains are packed with easterners. All come looking for work." An Uyghur said, "Our biggest fear is that we will be wiped out by their numbers." Many experts feel there are far more Han Chinese in Xinjiang than are reflected in the statistics.

Even today, the Chinese regard Xinjiang as a mysterious place. The lifestyle of some of its people has changed little since the 13th century when Marco Polo visited the region and nomads lived in the mountains and settled people lived around the oases, where the Silk Road caravans stopped. Some of the people in western China who live outside the cities are shepherds and herders who live in felt tents known as yurts. Among them are Kazakhs, Kyrgyz and Tajiks, minorities that occupy the former Soviet republics of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan on the Chinese border, and Mongolians.

The people in Xinjiang are very different from those found in the rest of the country. Describing a market in Turfan, the writer Paul Theroux wrote: "half the women...had the features of fortune-tellers, and the others looked like Mediterranean peasants— dramatically different from anyone else in China. These brown-harried, gray-eyed, gypsy-featured women in velvet dresses—and very buxom, some of the them—were quit attractive in a way hat was the opposite of the Oriental. You wouldn't be surprised to learn they were Italians or Armenians."

Uyghurs

Uyghurs are a Turkic-speaking Muslim people who live primarily in the autonomous region of Xinjiang. Described by some as Muslim Mongolians who look like Italian peasants, they are generally larger and darker and have more Mediterranean features than Han Chinese. Blue eyes and light skin are not uncommon among them. Uyghurs mostly follow moderate traditions of Sunni Islam, and culturally have more in common with similar people across Central Asia than with Han Chinese.

The Uyghur (pronounced WEE-gur) are also known as the Uygur, Uighur, Uigur, Weigur,Aksulik, Kashgarlik, and Turfanlik. They are one of the largest ethnic groups in China and the largest ethnic group in Xinjiang. They have traditionally occupied oasis cities in western China that were once major caravansaries on the Silk Road trade route. In those days it was said that Uyghur merchants could count in 50 languages. The story of Xinjiang is primarily the story of the Uyghurs. (See Xinjiang).

Christopher Bodeen of Associated Press wrote: “The Uyghurs are Central Asian people who are ethnically, culturally, linguistically and religiously distinct from Han Chinese. They are distantly related to the people of modern Turkey, where thousands of Chinese Uyghurs live in exile. There about 10 million Uyghurs in China, mostly in Xinjiang, but also scattered throughout the country, where they work in factories and restaurants that are known for their distinctive cuisine based around lamb kebabs and flat bread known as nan. They are generally poorer and less educated than Han Chinese, a result, Uyghur activists say, of linguistic bias and economic marginalization. [Source:Christopher Bodeen, Associated Press, May 22, 2014]

Uyghurs are descendants of wolves according to the Uyghur creation myth. Chinese are descendants of dragons according to their creation myth. For the most part Uyghurs didn't convert to Islam until the 15th century. For five centuries before that the name “Uyghurs” was used to describe Buddhist and Nestorian oasis dwellers in Xinjiang. In official Chinese government propaganda Uyghurs are described as “colorful, quaint folks."

The Uyghur are the main nationality in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Nanjiang, which is to the south of the Tianshan Mountain, is their main settlement region. "Uyghur" is the name that they call themselves. It means "union", "alliance" and "providing help". Many Uyghurs live in villages and concentrated communities of areas such as Karsh, Hetian, Akesu and Ku'erle, south of Tianshan Mountain in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Others, are scattered throughout Ili north of Tianshan Mountain, Taoyuan, and, Changde of Hunan Province.

Uyghur population in China: 0.7555 percent of the total population; 10,069,346 in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census; 8,405,416 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 7,214,431 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. [Sources: People's Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

See Separate Articles UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com ; UYGHUR LIFE, MARRIAGE, HOMES AND FOOD factsanddetails.com UYGHUR CULTURE. LITERATURE, KNIVES AND HIP HOP factsanddetails.com See Separate Articles on UYGHURS AND XINJIANG factsanddetails.com

Xinjiang Religion

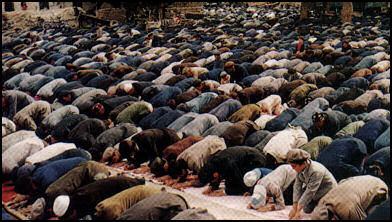

About 8.5 million of China’s 25 million Muslims live in Xinjiang. About 23,000 of China’s 30,000 mosques are in Xinjiang.

Many Xinjiang Muslims practice the mystical and relatively liberal Sufi form of Sunni Islam. Some women wear veils but some also wear miniskirts. Some veiled women wear high heels and knee-length skirts. There are more veiled women in the Kashgar area than in northern Xinjiang. Even conservative women routinely lift up thick brown veils in the markets to examine products.

Islam is important to the Uyghur’s identity but is not very deep rooted as a religion. Most Uyghur are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school. Some are followers of Sufi sects. The worship of Islamic saints (mazar) is widely practiced. Many Uyghurs visit the tombs of popular holy men. Uyghur Sufis chant sacred words. Whirling-dervish-type rituals are performed in front of mosques in Kashgar.

Shamanist and animist traditions endure. In some places shaman chant Koranic passages to heal the sick and people wear amulets with Arabic script to ward off evil spirits. In the old days there were descriptions of shaman dancing around ropes hung from ceilings, chanting Koranic verses and beating patients with dead chickens to exorcize evil spirits.

Transportation in Xinjiang

Although Xinjiang has fabulous landscapes, its tourism development has long been hampered by poor transportation. Attractions are scattered throughout the region, and it can a long time to travel from one place to another and to do so sometimes is expensive. To visit all the main sights in the region can two weeks or more but to main main ones can be done fairly easily on trains that connect Urumqi with Kashgar and Turpan and Chinese cities to the east.

Northern Xinjiang cities like Urumqi and Turpan can be reached by train. The Silk Road city of Kashgar in the south can be reached from Pakistan via the Karakorum Highway or by a new train that began service in 2004. The Iron Rooster was the name of train that carried people on the longest railway journey in China (4½ days) between Beijing to Urumqi. It was also the name of a book on China by Paul Theroux. The name, Theroux was told, implies stinginess because "a stingy person does not give away even a feather — nor does an iron rooster."

Roads are built through dune areas in the Taklamakan Desert near Khotan. Global positioning system are used for survey work. To prevent the development of quicksand, reed grasses are planted along the road. New highways and trains move workers, oil men, prospectors and engineers from place to place and allow consumer good to be shipped in and wool and agriculture products shipped out. Still in many places, donkeys and carts are are the prevalent forms of transportation.

Trains in Xinjiang

Lanzhou - Xinjiang High Speed Train cover the 1,776 kilometers (958 mile) distance between the two cities in 11 hours Four pairs of fast trains run between Lanzhou and Urumqi each way, each day. A second class seat ticket costs CNY551. The service began in 2014. Trains reach speed of 200 km/h (124 mph). Stops include Lanzhou West Station, Xining, Zhangye West, Jiayuguan South, Kumul (Hami), Turpan North, Urumqi. [Source: Travel China Guide]

Two trains operate between Beijing and Urumqi each way, each day. The trip takes 30.5 to 40 hours. For a long distance trip like this, passengers are highly recommended to get a hard sleeper or soft sleeper so they get enough sleep. Two fast trains and seven normal ones operate between the Beijing and Lanzhou each way each day. The fast ones take 8.5 to 9.5 hours and the slower ones take 16 to 28.5 hours. Traveling by air is the quickest way to get there and not that much more expensive.

There are seven of normal trains a day, each way, between Urumqi and Kashgar. The 1,475 kilometer (917 mile) trip takes 17.5 to 25 hours. The hard sleeper ticket is around CNY349.5 per person and the soft sleeper bed is about CNY521.5 per person.

Urumqi is served by several conventional rail lines. Ürümqi is the western terminus of the Lanzhou–Xinjiang (Lanxin) and Ürümqi–Dzungaria (Wuzhun) Railway, and the eastern terminus of the Northern Xinjiang (Beijiang) and the Second Ürümqi–Jinghe railway. The Beijiang and the Lanxin Lines form part of the Trans-Eurasian Continental Railway, which runs from Rotterdam through the Alataw Pass on the Kazakhstan border to Ürümqi and on to Lanzhou and Lianyungang.

High-Speed Trains Tighten China’s Grip on Xinjiang

Simon Denyer wrote in the Washington Post, “The brand-new bullet train slices past the edge of the Gobi desert, through gale-swept grasslands and past snowy peaks, a high-altitude, high-speed and high-tech manifestation of China’s newly re-imagined Silk Road meant to draw the country’s restive west ever tighter into Beijing’s embrace. The $23 billion, high-speed train link, which is still being tested in winds that can sometimes reach up to 135 mph, is just one symbol of that broader determination: to cement China’s control over its Muslim-majority Xinjiang region through investment and economic growth, secure important sources of energy and escape any risk of encirclement by U.S. allies to the east.[Source: Simon Denyer, Washington Post, September 10, 2014 ^*^]

“The train will run from Lanzhou to Xinjiang’s capital, Urumqi; for the longer term, China is even talking about trying to extend the high-speed network through Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Turkey to Bulgaria. “The high-speed railway will build the foundation for the Silk Road economic belt,” Erkin Tuniyaz, vice chairman of the regional government, told reporters after a recent news media trip on the train. “Xinjiang will be the biggest beneficiary of the Silk Road. It will help it open up further, increase trade, tourism and other exchanges with neighboring countries. It’s a historical opportunity for Xinjiang.” ^*^

The first high-speed railway in Xinjiang started commercial operation in late 2014. The high-speed train, which will cut traveling time from Lanzhou to Urumqi to eight hours from 20, is both a symbol of that investment and a useful tool if the government wants to encourage even more Han migration west. ^*^

Tourism Trains in Xinjiang

China Daily reported: “Traveling in the vast Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region by train has become a popular choice for domestic visitors, helping a region that was once restricted by poor transportation embrace a boom in tourism. First launched on July 1, 2013, the so-called "tourism trains" have expanded their routes and offer better services. These routes now cover main attractions such as Kanas, Turpan and Kashgar, and the trains are now equipped with bathrooms, gyms, catering services and entertainment rooms, helping to ensure a good traveling experience. [Source: China Daily, October 4, 2019

“So far, 19 provincial regions in other parts of the country have tourism trains that travel to Xinjiang, according to Lin Wen, deputy director of the tourism department of the Xinjiang Railway Tourism Development Co. He said about 121 domestic tourism trains were in operation so far. That number will climb to 200 by the end of this year.

“Huang Tingfen, the company's deputy general manager, said that they are making efforts to connect tourism trains with attractions in neighboring provinces for example, Dunhuang in Gansu province which is famous for its wall paintings and, in the future, to connect countries and regions in Central Asia.

“Yang Yulan, a 65-year-old from Urumqi, said that she enjoys traveling the region by trains. "I took the tourism train together with my son and husband in July, and it's quite convenient and relaxing," she said. She said that they could take time appreciating every single attraction along the train lines while getting a good rest at night on the train. "We don't need to carry any luggage or worry about missing vehicles like the group tour we used to join. Taking the tourism train is a good choice for us senior travelers," she said.

Xinjiang-Tibet Highway

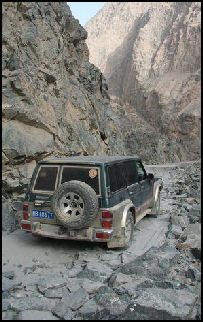

Xinjiang -Tibet Highway, Route No 219 National Trunk Highway, starts from Yecheng county of Xinjiang and ends at Lhaze county of Shigatse Prefecture in Tibet. It runs 1,455 kilometers, winding its way among mountains and rivers. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

Xinjiang -Tibet Highway, Route No 219 National Trunk Highway, starts from Yecheng county of Xinjiang and ends at Lhaze county of Shigatse Prefecture in Tibet. It runs 1,455 kilometers, winding its way among mountains and rivers. [Source: chinaculture.org, Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China]

Construction of the highway began in March 1956 and finished October 6, 1957. It climbs over 10 soaring mountains, including the Kunlun and Gangdisi mountains, with the highest elevation reaching 5,433 meters. Most areas it crosses are 4,000-5,000 meters above the sea level. It then goes southbound along the north slope of the Himalayas and crosses deserted land in the west.

A spectacular view of the holy mountain Kailash and the holy lake Lake Manasarowar (Mampang Yumco) can be viewe from the road. Many famous attractions and historical sites are also seen. Numerous Tibetan antelopes and wild donkeys and occasionally wild yaks and wolves are seen.

Xinjiang-Tibet Highway is the principal thoroughfare for Ngari Prefecture's and also an important defense trunk highway. It plays a major part in the economic development of Ngari, maintaining social stability, improving people's life and consolidating the southwest frontier defense. On a section of the highway in Xinjiang in 2011, David Hamilton of highadventure.org wrote: “The road passed through some dramatic mountain scenery crossing two high passes, the first at 3,150m and the second at over 5,000m. For several hundred kilometers we drove through a huge construction site employing hundreds of large earth moving machines, and thousands of Chinese labourers. Even after we left the main road there was still a lot of building work on the 'side' road from Mazar to Yilik.”

Developing the Southern Silk Road in Xinjiang

Simon Denyer wrote in the Washington Post, The Chinese “government is also hoping to promote a “southern Silk Road” that would pass through southern Xinjiang and revitalize ancient trading posts such as Kashgar and Hotan. Plans to establish textile factories hold out the promise of jobs, while the eventual extension of the high-speed train on a new route to the south is supposed to promote what the Communist Party calls a more “modern” way of thinking. [Source: Simon Denyer, Washington Post, September 10, 2014 ^*^]

“The building of the Silk Road, the south route, will help the ethnic groups become more open and modern,” said Lai Xin, a senior official at Xinjiang’s Development and Reform Commission, a key policymaking body. “As long as modern things enter Xinjiang, it will affect people’s way of living and production, and will change their way of thinking. We have to do something. We can’t leave them alone just because their way of thinking is backwards.” ^*^

“Yet, as two Uyghur scholars in Urumqi studied a map showing a new line for a high-speed passenger train, and the old railway line soon to be largely devoted to freight traffic, they could not escape a wry conclusion. “The resources from Xinjiang are going one way, and people from the mainland are coming the other way,” one said to the other. ^*^

“Restrictions on the ability of Uyghurs even to get passports, as well as the way the Han Chinese have so far monopolized the fruits of development in Xinjiang, do not bode well. “If done well, the Silk Road could have a huge impact on Xinjiang and bring real development momentum,” said one of those scholars, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to comment to journalists and was fearful of inviting punishment. “But it is doubtful how much benefit the Uyghur people will get,” he said. “We need good policies, otherwise it will cause the divide between ethnic groups to widen even further — and that would be a disaster.”

Xinjiang and Central Asia

Xinjiang borders Pakistan, Afghanistan, Mongolia and the former Soviet Central Asian states of Tajikistan,Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Many of the Muslims in Xinjiang feel a greater affinity to the people in these countries. In some places Chinese Kazahks, Uyghurs and Kyrgyz can cross the border easily. Some people routinely cross the borders on horseback without passing through immigration to see relatives.

Beijing has extracted promises from the Kazakstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan not to support separatist movements in Xinjiang in exchange for favorable trade terms. Many Uyghurs feel betrayed by their Central Asian neighbors for making a deal Beijing and not doing more to help them.

Today many of the people that cross the border between western China and the former Soviet republic are traders. In 1984, a year after the pass between western China and Soviet Kazakstan reopened, 25,000 tons of good crossed the border. In 1993, the trade had expanded to 422,000 tons. Most of the buyers come to China from Kazakstan to load up on candy, beer, clothing, toys, sewing machines, irons, tools, shoes, Chinese stereos, Korean televisions and Japanese cameras and even Chinese vodka to sell back home. The trade is lucrative that a Hong Kong entrepreneur is building a huge shopping mall and hotel near the border.

Simon Denyer wrote in the Washington Post, “As the United States enacts a strategic rebalance or “pivot” toward East Asia and withdraws troops from Afghanistan, China is responding with its own “pirouette” in the opposite direction, turning its face toward Central Asia and the West, said James Leibold, a regional specialist from La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia. Long-term stability. [Source: Simon Denyer, Washington Post, September 10, 2014]

Ilham Tohti told Al-Jazeera religious restrictions are part of Beijing’s attempts to secure its business inroads in Central Asia, which analysts say is set to become a leading source of China’s natural energy imports. “China is opening up its foreign affairs to the West. They hope not to have any problems as they expand their influence, especially not in Xinjiang. They are worried about this danger,” Tohti said. “In (his visit to) Central Asian states, President Xi was really pointing out a Uyghur terrorist threat,” said Sean Roberts, a George Washington University professor specializing on Chinese and Central Asian affairs.“In context of U.S. military pull-out of Afghanistan, China is concerned about ruffling feathers of Muslim populations to the West, as they have large plans of expansion of influence into Pakistan and Central Asian Muslim majority countries,” he said. [Source: Massoud Hayoun, Al Jazeera America, September 18, 2013]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Mongabey; CNTO; Louis Perrochon ; University of Washington

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2021