SALAR MINORITY

Salar

The Salar are a small dark people who wear embroidered jackets and round felt hats. Closely related to Uighurs and Uzbeks, the live mostly in Xunhua Salar Autonomous County in Qinghai Province and elsewhere in Qinghai and Gansu Provinces. The Salar call themselves "Salar", or "Sala" for short. They are the product of the long-term merging of people that moved east to the Xunhua region from Samarkand in Central Asia in the 13th century with the surrounding Han, Hui, Mongolian and other ethnic groups. In the past they were known by various names, including "Sala", "Salar" and "Shala". After the founding of new China, they was formally named the "Sala nationality".

The Salar are Sunni Muslims. Their beliefs are divided into the "old religion" and "new religion". Most Salar are Hafanai Muslims who converted to Islam in 17th and early 18th centuries and have been involved in several Muslim revolts. The national government removed the clergy (mullahs) in 1958 and religious activity was forbidden during the Cultural Revolution but has revived since 1980.The dead are buried without coffins in a Muslim funeral. Money, tea leaves, salt and other goods is thrown into the grave. There is a funeral feast three days after the burial. The deceased are buried in cemeteries without coffins. Relatives toss money, tea leaves, salt, and other goods into the grave. There is a funeral feast three days after burial.

The Salar language belongs to Turkic language group in the Altai language family as is similar to the language of the Uyghurs and Uzbeks. It is divided into two local dialects— Jiezi and Mengda—and has incorporated many Chinese and Tibetan loan words. Nowadays, most young and middle-aged Salars know how to speak Chinese. Written Chinese is also accepted as the written language of the Salar.

Most Salar are farmers, with lumbering, salt-producing, wool-weaving and animal husbandry serving as subsidiary industries. They mainly grow wheat, Tibetan barley, buckwheat and potatoes. The Salar manage many orchards and are famous for growing pears, apricots, grapes, Chinese dates, walnuts, melons and other fruits. The Xunhua region where they hail from is known as "the land of melons and fruits". The region’s egg shell walnuts are particularly famous.

See Separate Articles Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com and Small Minorities in Xinjiang and Western China factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Xinjiang Wikipedia Article Wikipedia Xinjiang Photos Synaptic Synaptic ; Maps of Xinjiang: chinamaps.org;Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; People’s Daily (government source) peopledaily.com.cn ; Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Folklore of China's Islamic Salar Nationality” by Wei Ma , Ma Jianzhong, et al. Amazon.com; “Salar Zhi Ling” (Music) by Zhanxiang Han Amazon.com; “Ethnic Minorities of China” by Xu Ying & Wang Baoqin Amazon.com; “Handbook on Ethnic Minorities in China” by Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “China's Ethnic Minorities” by Xiao Xiaoming Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Vol. 6, Russia and Eurasia/China” (1994) by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond Amazon.com; “The 56 Colorful Ethnic Groups of China: China's Exotic Costume Culture in Color” by Xiebing Cauthen Amazon.com ; “The Music of China's Ethnic Minorities” by Li Yongxiang Amazon.com; Northwest China: “Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China”by Jonathan N. Lipman Amazon.com; “Securing China's Northwest Frontier” by David Tobin” Amazon.com; Muslims: “Islam in China” by James Frankel Amazon.com; “China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law (Cambridge Studies in Law and Society) by Matthew S. Erie Amazon.com ; “Ethnic Identity in China: The Making of a Muslim Minority Nationality” by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “Ethnographies of Islam in China” by Rachel Harris, Guangtian Ha, et al. Amazon.com; “Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; Xinjiang: “Xinjiang: China's Central Asia” by Jeremy Tredinnick Amazon.com; “Xinjiang and the Modern Chinese State” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com “Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland” by S. Frederick Starr Amazon.com

Salar Population and Where Salar Live

Where the Salar live

Salar are the 36th largest ethnic group and the 35th largest minority out of 56 in China. They numbered 130,607 and made up 0.01 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Salar population in China in the past: 104,521 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 87,697 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 30,658 were counted in 1953; 69,135 were counted in 1964; and 68,030 were, in 1982. People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

The Salar live mainly in Xunhua Salar Autonomous County and Hualong Hui Autonomous County in Qinghai province and Jishishan Baoan, Dongxiang and Salar Autonomous County in Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture, Gansu Province and other places. In the 1990s about 70 percent of them lived in Xunhua Salar Autonomous County, Qinghai Province. Most of the remainder live in Hualong County, Qinghai Province, and in Linxia County, Gansu Province. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Xunhua County, which has the largest group of the Salars live, is a mountainous area situated along the banks of the Yellow River in southeastern Qinghai Province. Although it has a mild climate and fertile land crisscrossed by canals, it is handicapped by insufficient rainfall. Before China’s national liberation in 1949, farmers here did not have the capability of harnessing the Yellow River, and the county was often referred to as "arid Xunhua." [Source: China.org |]

Salar History

There have been different theories put forward on the origin of the Salars. The most prevalent one is that the ancestors of the Salars came from the region of Samarkand in Central Asia during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and lived for many centuries under Mongol rule. They began migrating to Qinhao around 700 years ago, mixed with Tibetan, Hui and Han people and were crushed by the Qing dynasty after they revolted in 1781. [Source: China.org |]

Salar people call themselves “Salar”, or “Sala” for short. Some people think that Salar people are descendants of the Salur tribe which belonged to the Oghuz Turks tribe of the Western Turkic Khaganate. Legend has it that Salur is the grandson of Uyghus Khan. The word “Salur” means “people who wave swords, hammers and spears everywhere”. They lived within China’s border during the Tang Dynasty and then moved west towards Central Asia. During the Yuan Dynasty, they moved through Samarkand and went back to China and settled down near Xining. According to their legends, their ancestor Karaman had opposite opinions with the King, so he left Samarkand with some of the tribe members, bringing white camels carrying water, soil and the Koran. They moved towards the east and came to Xunhua. They saw that Xunhua is vast and abounds with fertile grasslands and dense forests, so they decided to settle there. After that, these people intermarried with the local people of Hui, Tibetan, Han and some other minorities, and eventually formed the Salar people. Salar ethnic minority has a history of around 700 years. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

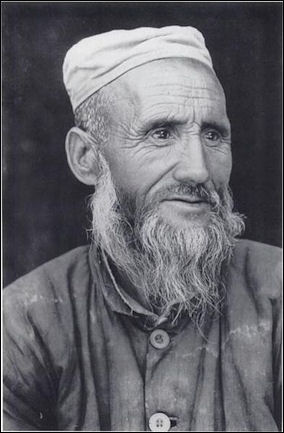

Salar man in the 1930s

During the Yuan Dynasty, a Salar headman bearing the surname of Han was made hereditary chief of this ethnic minority. With the rise of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), he submitted to the new rulers and continued to hold his position. He had under him a basic bureaucracy which looked after such things as military affairs, punishments, revenue and provisions. Following the development of the economy and the expansion of the population, the region inhabited by the Salars was divided into two administrative areas, i.e. the "inner eight gongs" of Xunhua and the "outer five gongs" of Hualong, during the early period of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). A "gong" included a number of villages, equivalent to the later administrative unit of "xiang" (township). During both the Ming and Qing periods Salar men were constantly subjected to conscription, which was an extremely heavy burden on the Salar people. |

According to the Chinese government Marxist view of history: As the Salars were devout Muslims, the villages were dominated by the mosques and the Muslim clergy. Along with the development of the feudal economy, land became concentrated in the hands of the ruling minority — the headman, community chiefs and imams. Prior to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the landlord economy was dominant. Relying on their political power, and feudal and religious privileges, the Salar landlords maintained ownership over most of the land and farm animals, as well as water sources and oil mills. Most of the Salar farmers, on the other hand, were either landless or owned only a very insignificant portion of barren land. They were subjected to crippling land rents and usury, in addition to all kinds of heavy unpaid labor services including building houses, felling trees and doing transportation work for the landlords. As a result, at times there were large-scale exoduses of Salars from their villages, leaving the farmlands lying waste and production at a standstill. |

Salar’s Journey from Samarkand

On the source of the Salar, historical records are extremely brief. But there is no shortage of oral legends on the subject. According to the most common and representative legend: Long, long ago, in Samarkand in present-day Uzbekistan, Asia, there was a nomadic tribe named Salur. Two brothers— Galemang and Ahemang—belonged to this tribe. They were industrious, kind-hearted, and brave and resourceful, and were greatly supported and deeply loved by the tribe. However, a narrow-minded king envied them very much, saw them as thorns in his flesh, and wholeheartedly wanted to eliminate them. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

Volumes of the Salar Quran in Kehtsikung Qinghai brought in 1371 from Samarkand

To prevent persecution of the tribe, the brothers led 18 clansmen, and a white camel, carrying the water and soil of their hometown and a Koran, left Samarkand and set off to the east in search of a new homeland. Then another 45 people followed them. They scaled mountains, forded streams, crossed deserts and entered Qinghai from Xinjiang, finally reaching and settling in Xunhua. They shared the region with local Tibetans, Hui and other ethnic groups. The Salar lived in harmony with these groups, intermarried with them, multiplied and gradually formed the Salar nationality. ~

Although this story has been embellished and dramatized the basic facts have been borne out by research by scholars of the Salar’s language, DNA, customs and habits, folk legends, historical records and family names. Historical records describe the Wugusi tribe—the ancestors of the Salar—as a Turkic tribe that immigrated to the east from Central Asia to Xunhua after the Mongol invasions of the area around Samarkand 800 years ago. ~

The Salar people have not forgotten their place of origin and the immigration history of their ancestors. Their migration story is relived in "Duiwei aoyina" (camel drama). See Below

Salar Food, Villages and Houses

The Salar have traditionally lived in villages with their own mosque and cemetery and resided in mud brick courtyard houses not unlike those of the Uzbeks in Uzbekistan. Within the courtyards they raise fruit trees. Around their villages they grow wheat, barely, buckwheat, potatoes, walnuts, vegetables, melons, apples, grapes, apricots and other fruits. The also raise sheep for mutton and wool.

Their houses are mainly built of wood and mud with flat roof, and they are surrounded by adobe walls on four sides to form a yard. Inside the house, there are usually Arabic calligraphies in Kufi script pasted on the wall. They place white stones on the top of the corner of the yard walls, which is similar to what the local Tibetans do. Salar men are known as skilled woodcarvers. They embellish doors widows, rafter and colonnades with their designs.

The Salar mainly live on wheat, highland barley, buckwheat, potatoes and various kinds of vegetables. The staples of their diet have traditionally been noodles, steamed buns and vegetable soup. According to Chinatravel.com: “During festivals or the occasions of receiving a visitor, they cook fried pastries, boiled mutton, steamed sugar buns and many other food to celebrate the festival or serve the guests. Milk tea and barley tea are the favored drinks loved by all the Salar people. Every household has tea wares such as pots, bowls and covered bowls. They like eating beef, mutton and chicken. They are forbidden to eat pork, donkey meat, mule meat, horse meat, blood and animals that die naturally. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

Salar Marriage, Customs and Taboos

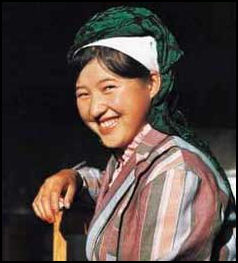

Newlywed Salar girl

Deeply influenced by Islam, the customs and habits as practiced among the Salars are roughly the same as those of the Huis that live nearby. Women like to wear kerchiefs on their heads and black sleeveless jackets over clothes in striking red colors. They are good at embroidery and often stitch flowers in five different colors onto their pillowcases, shoes and socks. Men wear flat-topped brimless hats of either black or white colors, and wear sheepskin coats without linings and woolen clothing in winter. Young men living along the banks of the Yellow River love to swim. [Source: China.org |]

When visiting Salar people’s home, the guest should hold the tea bowl when the host serves tea. When eating steamed bread, they should split it into pieces firstly and then begin to eat, instead of eating the whole. When Salar people are attending religious ceremonies, it is forbidden to walk in front of them. It is not allowed to wash clothes near wells and ponds. When talking with others, it is not polite to cough or blow the nose. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Traditionally, Salar parents picked their children's mates, using a matchmaker in negotiations. A bride-price of between one and four horses, along with cloth and sugar, was usual. The wedding took place in the bride’s home, with the bride herself listening to the ceremony from inside the house, and was conducted by the village ahung (Muslim priest). The wife lived with the husbands family. Divorce was solely based on the wishes of the husband, who simply had o say “I don't want you any longer," to send his wife from the house. No woman could divorce her husband; if she left him without his consent, she could not remarry. The Chinese government has prohibited polygyny.

According to the Chinese government: “Some of the customs and habits of the Salars have changed over the years as a result of social and economic development. Polygamy, for instance, has been abolished, and cases of child marriage have been greatly reduced. The extravagant practice of slaughtering cattle in large numbers for weddings, funerals and festivals has been changed. Women of the Salar ethnic minority in the past suffered tremendously under religious strictures and feudal ethics. Unmarried girls were not allowed to appear in public, while married women had to hide their faces in front of strange men. They had to turn their faces sideways when answering an inquiry and make a detour should they meet a strange man coming their way. But, in recent decades, Salar women have broken away from such practices and the traditional concept of men being superior to women is slowly disappearing. Salar women are now taking an active part in all local production endeavors. |

Salar Clothes

The clothes of the Salar are influenced somewhat by their Islamic and animal herding traditions and Central Asian origins. In the old days, clothing for men included a cross-collar gown, trousers with a big crotch, cloth belt or silk scarf around the waist, sheepskin rolled brim hat and ankle boots. Salar women wore silk scarves and a dresses. Over the centuries the styles of the Han Chinese, Hui, Tibetans and other ethnic groups have their impact on the Salar. Salar clothes are generally either short and loose, or long and fitting. Older people wear long robes, which is called “Dong” in Salar language. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums ~]

These days a traditionally-dressed Salar man wears a little white or black skullcap-like round hat or hexagonal hats with no brim, a white "undershirt" (shirt), a black or sleeveless jacket, a red cloth or red silk belt around the waist, and black or blue trousers. When the old people pray at a mosque, they sometimes bind a white "dasida'r" (scarf) around their head and and wear a gown called a "zhongbai". [Source: Chinatravel.com ~]

These days a traditionally-dressed Salar man wears a little white or black skullcap-like round hat or hexagonal hats with no brim, a white "undershirt" (shirt), a black or sleeveless jacket, a red cloth or red silk belt around the waist, and black or blue trousers. When the old people pray at a mosque, they sometimes bind a white "dasida'r" (scarf) around their head and and wear a gown called a "zhongbai". [Source: Chinatravel.com ~]

Salar women like wearing bright colored clothes with big images of flowers in the front and a black waistcoat. They like wearing accessories like long-string earrings, rings, bracelets and beads. A traditionally-dressed Salar women wear a colored coat with the buttons of the front on the right, a black or purple sleeveless jacket, trousers, embroidered shoes and a headscarf . Women usually wear hats with long veils influenced by Islamic culture. The colors of headscarf differ according the ages, with young girls and newly wedded women wearing green headscarf, middle-aged women wearing black ones and the old women wearing white headscarves. In Hualong area, some of their costumes have the characteristics of Tibetan style.\=/ ~

Huarer Singing Festival

The Huaer Festival lasts for five days and is celebrated between the 4th and 6th lunar months in May, June or July by the Han, Hui, Tu, Sal, Dongxiang and Baoan peoples in the northwest provinces of Ningxia, Gansu and Qinghai. A huaer is a kind of folk song that is popular among these people. Most huaer songs are improvisations, sung by one or two people, with long and prolonged sonorous tones which have both a lyrical and a narrative content.

The festival is usually celebrated in a big square decorated with hanging red lanterns and colorful streamers. The festivities open with gongs, drums and fireworks. At night bonfires are built and sometimes the singing and dancing goes until dawn. In some places older singers put ropes around the festival site and people can't enter until after they have sung a song.

In the singing competitions, which are held on a stage, singers are given a subject and they quickly have to compose a song about it. There are individual, duet and team competitions and participants are judged on their singing, their improvisations and their words. Sometime the singing is gentle and soft. Other times it is more forceful.

Hua’er was inscribed in 2009 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. According to UNESCO: In Gansu and Qinghai Provinces and throughout north-central China, people of nine different ethnic groups share a music tradition known as Hua’er. The music is drawn from an extensive traditional repertoire named after ethnicities, towns or flowers (‘Tu People’s ''ling’,'' ‘White Peony ''ling’''), and lyrics are improvised in keeping with certain rules – for example, verses have three, four, five or six lines, each made up of seven syllables. [Source: UNESCO]

See Huaer songs Under TU LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com and Festivals Under TU MINORITY factsanddetails.com

Salar Songs

Salar Turkmen in Xian

The Salar people have a rich and colorful tradition of folklore. Many of the legends, stories and fairy tales sing the praises of the courage and wisdom of the laboring people, and lament the hard lives of the Salar women in the past. The typical folk tune genre is the "Hua'er (flower)," a kind of folksong sung sonorously and unrestrainedly in the Chinese language. However, in most cases it is presented with a sweet, trilling tone due to the influence of Tibetan folk songs. The singers are all able to fill in impromptu words according to whatever happens to strike a chord in their hearts. Amateur theatrical troupes, and song and dance groups exist among the Salar people. [Source: China.org]

The Salar qu is a lengthy narrative song sung by the Salar in their language. Each Salar qu is made up of some short songs that focus on a theme, narrates a story, or expresses some kind of feeling, or conjures up image that can extended or improvised on from many angles and levels. The melody of Salar qu is beautiful, the rhythm is lively, and the words of song are vivid, and often humorous. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums]

Most Salar qu are "love songs" that express the love between male and female youths. Traditional songs date back to a time when marriages were mostly arranged and singers sang both of their love for the one they are betrothed to and the desire to break free from the marriage and be with their truly beloved. Feelings were often expressed through analogies. The structure of each qu complies with certain rules but otherwise is comparatively free. The number of sentences in each song phrase or short poem is fixed at four, six or eight sentences. Generally there are five words in each sentence, with certain words inserted to enhance the rhythm and melody. The last word of each sentence was pronounced rising and falling, melodiously. The songs aim to easily express the passionate and profound feelings of singers.

Among the Folk songs loved by the Salar are "Yu'r" (love song), Salar "Hua'r", banquet songs, folk rhymes, work songs, children's songs and cradle-songs. "Yu'r" is one of the main forms of Salar qu. These love songs have traditionally been sung by young people in fields, open country and other out-of-the-way places. Singing them in the villages and houses is strictly forbidden. "Yu'r" have traditionally been sung by young women and men who wanted to choose their partners. Famous Yu’r songs include Baxi Guliuliu, Salar Saixibuga, King Awuni and Beautiful Girl Jugumao.

Salar Camel Drama

"Duiwei aoyina" (camel dramas) are often performed at Salar weddings and festivals. In these dramas, there are four performers. The two who wear fur-lined jackets turned inside out are the the camels. The one who leads the camels with one hand— and wears a gown and has a "dasida'r" (white long tower) wrapped around his head—is the ancestor of Salar—Galemang, The forth performer is a local person (Mongolian). Through antiphonal singing (alternate singing by two choirs or singers) and dialogue, the story of the Salar’s arduous journey from Samarkand to Qinghai is told. ~

In the beginning part of the drama, two people engage in a dialogue. One asks and the other answers as they narrate the story of the long and arduous journey of the ancestors of the Salar. In the latter part, a person who acts as an Islamic teacher reads and sings verses in the Salar language, narrating how the ancestors of the Salar ended up into Xunhua. Generally, the performances are held under moonlight and the audience sits around in a relaxed manner participating in the dialogue.

Salar Goatskin Rafts

Animal skin raft called "leather boat" in ancient times have served as traditional sources of water transportation and ways to cross rivers for the Salar, Hui, Dongxiang, Baoan, Tu and other ethnic groups. The Salar have used to cross the Yellow River in Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia and other regions. They consist of a raft made from a lattice of wood sticks with leather bags bound under it. When it is placed in the water theleather bags face the water. Such a craft can not only carry people but also cargos. The carrying capacity of a small raft is about two to three tons, and that of a big raft, over 10 tons. The dead weight is light and the waterline is low so there are few worries about it running aground or being damaged by rocks. There rafts are flexible, able to absorb the pounding of rapids and rocks, and relatively maneuverable and easy to control. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums ~]

Most of the rafts are made from goatskins. Some are made with cowhide. To make one: 1) kill a goat, cut off its head, and remove the meat, bones and internal organs through the neck, leaving a complete goatskin. 2) Put the goatskin into water and soak it for several days. 3) Take it out and dry it in the sun for one day and scrape off all the hair. 4) Apply appropriate quantities of salt, water and vegetable oil, and expose it to the sun again until the outer skin goes red brown. 5) When assembling the raft, blow air into the skin and bind up the neck. The manufacturing methods for cowhide crafts are similar with that of goatskin rafts. ~

Skin rafts are strong and durable, and light enough that they can be shouldered, carried and moved by only one person. The Salar people in the region of Dahejia, Gansu province often use cowhide rafts when crossing the Yellow River. There are two kinds of cowhide rafts: big and small. The big cowhide rafts are bound with six to eight cowhide bags arranged in parallel rows, while the small rafts only have four cowhide bags, connected in a square shape, with sticks bound up horizontally over them. The big rafts can carrry more than 20 people, and the small rafts can carry seven or eight people. When crossing the river, the passengers sit on the middle part of the raft. Three to four sailors stand on the bow and stern of the raft, using oars and poles to guide and steer the craft, shout out work songs in unison. Generally, the raft drifts a considerable distance downstream before it reaches the opposite bank.

Pinching Fingers: Fixing Prices the Salar Way

The Salar are known for their business skills. Although it is rarely used anymore, they have a unique custom for negotiating prices and bargaining: Rather than speaking they “pinch fingers in sleeves.” The method works like this: when the index finger is pinched, it indicates 1, 10, 100, 1,000 or 10,000; when the index and middle fingers are pinched, it indicates 2, 20, 200, 2,000, or 20,000; when the ring finger is added, it indicates 3, 30, 300, 3,000, or 30,000; when the little finger is also added, it indicates 4, 40, 400, 4,000 or 40,000; when the five fingers are pinched together, it indicates 5, 50, 500, 5,000 or 50,000; when the thumb and little finger are pinched together, it indicates 6, 60, 600, 6,000 or 60,000; when the thumb, index finger and middle finger are pinched, it indicates 7, 70, 700, 7,000 or 70,000; when the thumb and index finger are extended, it indicates 8, 80, 800, 8,000 or 80,000; and when the index finger is pinched in a circle, it indicates 9, 90, 900, 9,000 or 90,000. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums ~]

When the parties are bargaining, generally the fingers are moved in long sleeves so no one can see them. After one of the bargainers says "How about this price?", the fingers do not stop moving until a reasonable price is agreed. If there is a great gap between the numbers, the two parties give up and try to find new trade partners. One example of how the bargaining process works is as follows: the first party first pinches the thumb and index finger of the second party, and then pinches the thumb, index finger and middle finger, and says: "just this price". Then the second party knows that the offering price is 87 yuan, 870 yuan or 8,700 yuan (which it is known through common sense based on the quality of commodities and going prices at the time of the bargaining session). ~

In the past, people bargained with fingers in their sleeves. Because the sleeves of the fur-lined jackets they wore in winter and the clothes they wore in summer are were very long and wide, it was very convenient to bargain in sleeves. These days, the sleeves of both the fur-lined winter jackets winter and summer clothes are very short, small and thin so it is so not convenient to negotiate prices in sleeves. Sometimes the bargaining is done under the front of the clothes or a sheepskin but the mode of pinching fingers has not changed.

Image Sources: Nolls, Wikimedia Commons, map Joshua Project

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022