KYRGYZ IN CHINA

Kyrgyz (Kirgiz) mainly live in the southwestern of Xinjiang especially in Kezhilesu Kyrgyz autonomous state. They also live in Yili, Tachen, Akesu and Kashi in Xinjiang. and Fuyu in Heilongjiang province. The Kyrgyz are regarded as the main ethnic group of the Pamirs, a mountain range in Russia, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan and China known for its 7,500-meter-high peaks and snowy plateaus. Kyrgyz are found in all of the Pamir countries.

Kyrgyz (Kirgiz) mainly live in the southwestern of Xinjiang especially in Kezhilesu Kyrgyz autonomous state. They also live in Yili, Tachen, Akesu and Kashi in Xinjiang. and Fuyu in Heilongjiang province. The Kyrgyz are regarded as the main ethnic group of the Pamirs, a mountain range in Russia, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan and China known for its 7,500-meter-high peaks and snowy plateaus. Kyrgyz are found in all of the Pamir countries.

Kyrgyz speak an Altaic language. Those in China have traditionally been organized into two major tribes, corresponding with different dialects spoken in the north and south. Most belong to the Ismaili sect of Shiite Islam. They practice ground burials and celebrate Muslim holidays. A few never became Muslims and practice shamanism or Tibetan Buddhism. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Kyrgyz have a long history and have been known in China by many names. In the Han dynasty they were called "Gekun"or "Jiankun". Later they were called "Qigu"in the Jin dynasty; "Jiankun", "Jikasi"or "Qiliqisi"in the Tang and Song dynasty; and "Jirjisi" or "Qirjisi" in the Yuan and Ming periods. All these names were based on "Kyrgyz", which has had different Chinese translation at different times. Kyrgyz people call themselves "Kyrgyz", which means "40 tribes", "40 girls" or "people on the prairie". In the Qing dynasty, they were called "Bulute", which means "Mountain residence". [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences~]

Kyrgyz people have traditionally made their living by raising and breeding horses, sheep and other stock animals. A few engage in agriculture. Herdsmen have traditionally lived in tent-like yurts. In the winter, they live in adobe bungalows. Their staple foods are meat, dairy products, rice and flour. Their traditional festivals include the "Nuolaozhi Festival", Gurbang Festival” and the “Rouzhi Festival.” During these festivals, events such as catching sheep, horse racing and wrestling are held. The Kyrgyz are regarded as excellent singers, dancers and storytellers.Their heroic epic Manasi (Manas) is 200,000 lines long. It is not only a literary treasure, but also a encyclopedia to study the history and culture of the Kyrgyz. The painting, embroidery and sculpture of the Kyrgyz also has a distinct character.~

See Separate Articles KYRGYZ NOMADIC LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com ; NOMADIC HERDERS IN CHINA AND EFFORTS THEM factsanddetails.com ;Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com and Small Minorities in Xinjiang and Western China factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Xinjiang Wikipedia Article Wikipedia Xinjiang Photos Synaptic Synaptic ; Maps of Xinjiang: chinamaps.org; Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; People’s Daily (government source) peopledaily.com.cn

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Meaning of Kyrgyz: a Book That Delves into the Identity of the Kyrgyz People” by Iskender Sharsheev Amazon.com; “Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China”by Jonathan N. Lipman Amazon.com; “Securing China's Northwest Frontier” by David Tobin” Amazon.com; Muslims: “Islam in China” by James Frankel Amazon.com; “China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law (Cambridge Studies in Law and Society) by Matthew S. Erie Amazon.com ; “Ethnic Identity in China: The Making of a Muslim Minority Nationality” by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “Ethnographies of Islam in China” by Rachel Harris, Guangtian Ha, et al. Amazon.com; “Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; Xinjiang: “Xinjiang: China's Central Asia” by Jeremy Tredinnick Amazon.com; “Xinjiang and the Modern Chinese State” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com “Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland” by S. Frederick Starr Amazon.com; Herders: “China's Last Nomads: History and Culture of China's Kazaks” by Linda Benson and Ingvar Svanberg Amazon.com; “Winter Pasture: One Woman's Journey with China's Kazakh Herders” by Li Juan, Nancy Wu, et al. Amazon.com

Kyrgyz Population

Where most Kyrgyz live China

Kyrgyz are the 32nd largest ethnic group and the 31st largest minority in China. They numbered 186,708 and made up 0.01 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Kyrgyz populations in China in the past: 160,875 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 141,549 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census, up from 66,000 in 1962. A total of 70,944 were counted in 1953; 70,151 were counted in 1964; and 108,790 were, in 1982. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

The Kyrgyz population in China represents about 7 percent of the world population of Kyrgyz. There are about 3.5 million Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan. They make about two thirds of the population there. Most of the Kyrgyz in China live in the Kizilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Region in the southwestern part of Xinjiang near Kyrgyzstan. Other are scattered in southern and northern Xinjiang and in Fuyu County in Heolongjiang Province.

About 80 per cent of the Kyrgyz in China live in the Kizilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture in the southwestern part of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The rest live in the neighboring Wushi (Uqturpan), Aksu, Shache (Yarkant), Yingisar, Taxkorgan and Pishan (Guma), and in Tekes, Zhaosu (Monggolkure), Emin (Dorbiljin), Bole (Bortala), Jinghe (Jing) and Gonliu in northern Xinjiang. Several hundred Kirgiz whose forefathers emigrated to Northeast China more than 200 years ago now live in Wujiazi Village in Fuyu County, Heilongjiang Province.

Origins of the Kyrgyz

The forefathers of the Kyrgyz lived on the upper reaches of the Yenisey River in present-day Siberia. The origin of the Kyrgyz is still a matter of some debate. Based on common burial customs, animist traditions and herding practices, it is believed that the Kyrgyz originated in Siberia. Kyrgyz is one of the oldest ethnic names in Asia. It was first recorded in the 2nd century B.C. in the "40 girls" legend of 40 original clan mothers.

The Kyrgyz are believed to have descended from nomadic tribes, the "Yenisey Kyrgyz," from the Yenisey River area in central Siberia. Their homeland is an Ireland-size chunk of land, covered by steppe and mountains, in the upper Yenisey River Basin near present-day Krasnoyarsk, They occupied this region between the 6th and 12th centuries, and are believed to have begun speaking a Turkic language around the 9th century.

The "Yenisey Kyrgyz” created an empire that stretched across Trans-Siberian and Central Asia from Kazakhstan to Lake Baikal from the 6th to the 13th century. They established ties with the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618-907) in China and were in the 8th century Orkhan inscription. In 840, the Kyrgyz defeated the Uighar tribes and occupied their lands in what is now northwestern Mongolia. The Kyrgyz in turn were driven off these lands by the Khitan the 10th century.

EARLY HISTORY OF THE KYRGYZ AND KYRGYZSTANSee Separate Article factsanddetails.com

History of the Kyrgyz in China

During the Liao and Song dynasties (916-1279), the Kyrgyz were recorded as "Xiajias" or "Xiajiaz". The Liao government established an office in the Xiajias area. In the late 12th century when Genghis Khan rose, Xiajias was recorded in Han books of history as "Qirjis" or "Jilijis," still living in the Yenisey River valley. From the Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368) to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the Jilijis, though still mainly living by nomadic animal husbandry, had emigrated from the upper Yenisey to the Tianshan Mountains and become one of the most populous Turkic-speaking tribal groups. After the 15th century, though there were still tribal distinctions, the Jilijis tribes in the Tianshan Mountains had become a unified entity. [Source: China.org |]

In the early Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the Kyrgyz, who had remained in the upper Yenisey River reaches, emigrated to the Tianshan Mountains to live together with their kinfolk. Many then moved to the Hindukush and Karakorum Mountains. At this time, some Kyrgyz left their homeland and emigrated to Northeast China. In 1758 and 1759, the Sayak and Sarbagex tribes of Eastern Blut and the Edegena tribe of Western Blut, and 13 other tribes — a total of 200,000 — entered the Issyk Kul pastoral area and asked to be subjected to the Qing. |

According to the Chinese government:“The Kyrgyz tribe was under the rule of the Turkic Khanate in the A.D. mid-sixth century. After the Tang Dynasty (618-907) defeated the Eastern Turkic Khanate, the Kyrgyz came into contact with the dynasty and in the 7th century the Kyrgyz land was officially included in China's territory. From the 7th to the 10th century, the Kyrgyz had very frequent communications with the Han Chinese. Their musical instruments — the drum, sheng (a reed pipe), bili (a bamboo instrument with a reed mouthpiece) and panling (a group of bells attached to a tambourine) — showed that the Kyrgyz had attained quite a high level of culture. According to ancient Yenisey inscriptions on stone tablets, after the Kyrgyz developed a class society, there was a sharp polarization and class antagonism. Garments, food and housing showed marked differences in wealth and there were already words for "property," "occupant," "owner" and "slave." [Source: China.org |]

The Kyrgyz played a major role with their courage, bravery and patriotism in the defense of modern China against foreign aggression. The Kyrgyz and Kazaks assisted the Qing government in its efforts to crush the rebellion by the nobility of Dzungaria and the Senior and Junior Khawaja. They resisted assaults by the rebellious Yukub Beg in 1864, and when the Qing troops came to southern Xinjiang to fight Yukub Beg's army, they gave them assistance. |

“Under the pretext of "border security," the Kuomintang regime in 1944 ordered the closing of many pasturelands, depriving the Kyrgyz herdsmen of their livelihood. As a result, the Puli Revolution broke out in what is now Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County and part of the Akto area, and formed a revolutionary government. This revolution, together with uprisings in Ili, Tacheng and Altay, shook the Kuomintang rule in Xinjiang. More than 7,000 people took part in the Puli Revolution, the majority being Kyrgyz, Tajiks and Uygurs. |

Chinese View of Kyrgyz Development

According to the Chinese government: “Before the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Kyrgyz derived their main revenue from livestock breeding, which was entirely at the mercy of nature. About 15 per cent of the population engaged in farming, which was done in a very primitive way: a slash-and-burn method, without deep ploughing and fertilizer application. The handicraft industry was undeveloped and remained but a household undertaking. There were workshops making horse gear, carpets, felt cloth, fur hats and knitting wool. Cooking utensils, knives, tea, tobacco and needles had to be bought with animals or animal by-products. Hunting was another important sideline occupation. [Source: China.org |]

Kyrgyz tents

“The long-standing feudal patriarchal system left a deep impact upon Kyrgyz economic life. Before 1949, 10 per cent of the population owned 70 per cent of the livestock. The masses of herdsmen owned very few or none of the domestic animals and had to work for the herd owners and farm landlords. Once a man was hired, his whole family had to graze domestic animals, milk cows, shear wool, weave and cook for the herd owner in return for only two or three sheep a year plus food and clothing. In the farming area, the landlord class plundered the poor peasants through labor hiring, land and water rent, and usury. Exploitation by religious leaders was also severe. The land owned by the Islamic clergy had to be tilled by peasants without pay and the taxes exacted by them accounted for 20 per cent of an average peasant's annual income. |

“The Kyrgyz tribal organization at that time was as follows: a major tribe had a number of sub-tribes, not necessarily herding in the same locality; each sub-tribe was composed of a number of "Ayinle," or clans; an "Ayinle" of five to ten families was a production unit as well as a traditional social organization; within the "Ayinle" there were customary relations of exploitation under the cover of "mutual clan assistance." The ties between tribes were very loose, and there were generally no relations of dependence. The tribal chiefs, mostly big herd owners, wielded a certain degree of political power. The rulers of the Chinese dynasties throughout history invariably tried to accelerate and worsen the contradictions among the tribes so that they could "divide and rule." “ |

Kyrgyz Language

The Kyrgyz language belongs to the Northwestern (Kipchak) division of the Turkic Branch of the an Altaic language family. It is closely related to Kazakh, Nogay, Tatar, Kipchak-Uzbek and Karakalpak and should not be confused with Yenisei Kyrgyz. Kyrgyz had no written form until the late 19th century. Before that time, “Turki,” a written form of Uzbek, was used. At the turn of the 20th century, after the Kyrgyz had become more Islamic, Kyrgyz was written using the Arabic alphabet. In 1924 the Arabic alphabet was modified to write Kyrgyz. In China, most Kyrgyz can speak Uyghur, Kazakh or Chinese. There are many borrowed words from the Chinese language. In the 1950s, a new alphabet was then devised, discarding the old Arabic script and adopting a Roman alphabet-based script but it was never widely embraced.

Mongolian, Kazakh, Manchu, Uygur, Turkish and other Altaic, Tungusic and Turkic languages are Altaic languages in the Ural-Altaic family of languages. Some linguists believe they are related. Other believe they share similarities because of the borrowing of words by traditionally nomadic peoples. Ural-Altaic languages include Finnish, Korean and Hungarian.

The languages of the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Mongols and Uyghurs are so similar that they can easily communicate with each other and often eat and party together when they live near one another. These languages are difficult to learn and speak. Travel writer Tim Severin wrote they sound “like two cats coughing and spitting at each other until one finally throws up..” Some of the more guttural sounds sound like someone is having difficulty breathing.

In the early 13th century, under Genghis Khan, the Mongols created a vertical script based on the Uyghur script, which was also adopted by many Turkic-speaking peoples and is related to the alphabets of Western Asia. It looks like Arabic written at a slant. The source of the Uyghur alphabets was the alphabet of the Sogdians, a Persian people centered around Samarkand in the A.D. 6th century.

Kyrgyz Religion and Festivals

The Kyrgyz are a Muslim people yet shamanism remains alive. People often pray to the mountains, sun and rivers more often than they bow towards Mecca and finger talisman under their clothes as much as they visit mosques. Most shaman have traditionally been women. They still play an important role in funerals, memorial, and other ceremonies and rituals.

In the first half of the 18th century, most of the Kyrgyz in Xinjiang believed in Islam. Those in Emin (Dorbiljin) County in Xinjiang and Fuyu County in Heilongjiang, influenced by the Mongols, followed Tibetan Buddhism, while retaining some Shamanistic legacies: Shamanistic "gods" were invited on occasions of sacrificial ceremonies or illnesses and the Shamanistic Snake God was worshipped. [Source: China.org |]

Most Kyrgyz are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school of law. They are regarded as only lukewarm Muslims. Islam has never been that important with the nomadic people and still isn't. You don’t see that many mosques nor hear the muezzin in Kyrgyz areas. This is due to their nomadic lifestyle, animist traditions, distance from the Muslim world, close contacts with Russians and Chinese and the suppression of Islam under Stalin and the Chinese Communists. Scholars have said the lack of strong Islamic sentiments is because of the Kazakh code of honor and law—the adat— which was most practical for the steppe than Islamic sharia law.

In the Kyrgyz calendar, similar to that of the Han people, the years are designated as years of the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, fish, snake, horse, sheep, fox, chicken, dog and pig. The appearance of the new moon marks the beginning of a month, 12 months form a year and 12 years is a cycle. At the beginning of the first month of the year, the Kyrgyz celebrate a festival similar to the Spring Festival. There are also Islamic festivals. On major festivals and summer nights, old and young, men and women, gather on the pasturelands for celebrations: singing, dancing, ballad-singing, story-telling and games which include competing to snatch up a headless sheep from horseback, wrestling, horse racing, wrestling on horseback, catching objects from racing horses, horseback shooting, tug-of-war and swinging. |

Kyrgyz Life in China

The Muslim Kyrgyz have traditionally been more settled than the Kazahks. They were skilled horsemen but they usually lived in permanent settlements — where they raise sheep, horses, cattle and sometimes yaks and camels — for nine months of the year and then moved to higher pastures for the summer. Their favorite drink is goat milk. The only crops they grew were potatoes, onions and cabbage. Other goods such as wheat flour, rice, tea, salt and sugar have traditionally been bought or traded for. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Nomadic Kyrgyz in China traditionally lived in yurts or square felt tens whereas the settled ones lived in mud brick houses. The men herded the animals, cut grass and hunted. Women, who traditionally dressed in flowery skirts and white head scarves, grazed the animals, milked and sheared them and did household chores.

Marriages have traditionally been arranged, often early in life. A man courts his bide with a roasted sheep. Before the wedding the couple are tied to post and are not set free until the groom’s family asks for “mercy” and offers gifts to the bride’s family. After a Muslim wedding the couple lives with the groom’s parents.

Kyrgyz Marriage and Family Customs

Marriages have traditionally been arranged by parents and extended family members .Some courting took place and the wishes of the potential bride and groom were often taken into consideration. A bride price was paid by the groom’s family and the marriage was sanctified in a betrothal ceremony, called a nikka, presided over by a mullah.

Couples were married young and girls were expected to remain virgins until they were married. Wealthy men sometimes had several wives. Generally Kyrgyz only married other Kyrgyz or Kazakhs. Kyrgyz that married Russians, non-Kyrgyz or non-Muslims were sometimes looked down upon so much they were forced to leave their home towns and villages. Marriages to the much hated Uzbeks, Tajiks and Uighurs were particularly frowned upon. Offspring from such unions were given low status positions in the clan.

In the old days, marriages were sometimes arranged before birth. This was called "marriage arrangement at pregnancy." Traditional courtship starts when the bridegroom calls on the bride's family with a roasted sheep. The relatives of the bride then tie the couple to posts in front of the tent. They will be released only after the father and brothers of the bridegroom ask for "mercy" and present gifts. The wedding is presided over by an imam who cuts a baked cake into two, dips the pieces in salt water and puts them into the mouths of the newly-weds as a wish for the couple to share weal and woe and be together for ever. The bridegroom then takes the bride and her betrothal gifts back to his home. [Source: China.org |]

At a traditional wedding party guests feast on pilaf, roasted mutton and other foods. Guests dance and sing and listen to storytellers recite parts the of the epic poem the Manas. After a Muslim wedding the couple lives with the groom’s parents.

The Kyrgyz family is generally composed of three generations, with married sons living with their parents. There is distinct division of labor at home: the men herd horses and cattle, cut grass and wood and do other heavy household chores, while the women graze, milk and shear the sheep, deliver lambs, process animal by-products and do household chores. Before liberation, the male was predominant and decided all matters of inheritance and property distribution. When the son got married, he was entitled to a portion of the family property which was usually inherited by the youngest son. Women did not have the right to inherit. The property of a childless male was inherited by his close relatives. When there is a funeral, all relatives and friends attend, wearing black clothing and black kerchiefs. |

Kyrgyz Food and Drink: Koumiss and Boiled Mutton

Kyrgyz people engage in livestock breeding as their main activity, so their foods are closely related to their economic life; meat and diary product are their staple food. Kyrgyz are Muslims so they don’t eat pork and other food restricted by that religion. Their main meat foods are mutton and beef. Sometimes they ear the meat of horses, camels and fish but they never eat the meat of dogs, cats, mice, donkeys, mules or raptors. Boiled mutton and the whole roasted sheep are the main dishes that they treat guests. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

To make boiled mutton is very simple: 1) the head, skin and innards of the killed sheep are removed; 2) then the sheep is chopped into pieces along the body; 3) it is boiled in clean water; 4) blood and grease in the soup are discarded when the water boils; 5) Lastly salt is added and the cooked mutton is served. The boiled mutton is held in wood dishes and put on a table. People eat the mutton with their hand only or knife. That is why the dish is called mutton served by hands of onself. Although boiled mutton is easy to cook, it is said to be so delicious it doesn’t need any accouterments (some Westerners might debate this). According to Kyrgyz tradition, the sheep tail is given to honored guests and the eldest man to show respect. When eating mutton, people are expected to take the piece in front of them and and not pick around for a particular piece. ~

Generally made in the summer, koumiss is the traditional beverage the Kyrgyz. To make it: 1) fresh horse milk or camel milk is stored in leather churns; 2) yeast is added; 3) then the mixture is stirred continuously, heated and fermented fore three or four days until it is ready to drink. Koumiss contains a little alcohol and it is very hard to get drunk off it. The Kyrgyz regard it as a healthy drink: full of protein, minerals, vitamins and sugar. Kyrgyz people have been fond of it since ancient times. ~

See Separate Articles FOOD IN KYRGYZSTAN factsanddetails.com ; KYRGYZ DISHES, RESTAURANTS AND SHEEP factsanddetails.com ; DRINKS IN KYRGYZSTAN factsanddetails.com

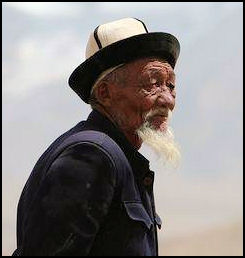

Kyrgyz Clothes and Hats

As the Kyrgyz are an animal herding people, their clothes tend to be made from the wool and leather of livestock animals they raise. Traditionally, men have worn robes; and women have wornskirts. Traditional men’s clothes includes loose trousers made of cotton or leather, high boots, an embroidered white round-collared shirts trimmed with lace and a qiapan (a knee- length robe that has long sleeves) made of sheep wool, camel felt or cotton cloth and has a leather or embroidered cloth waistband. Young lads wear narrow trouser with embroidery patterns on the cuffs, fronts, and borders of their clothes. Most men's clothes are black or white; blue and brown are also worn by young men. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Kyrgyz men in China have traditionally worn red, green, blue, purple or black cap made of corduroy; and on top of that cap they would wear another leather cap or pelt cap when needed. The most popular cap worn by Kyrgyz everywhere is the calpac, a traditional white felt hat with an upturned brim. It resembles a Robin Hood or leprechaun hat and often has designs on it. Many old Kyrgyz men wear it. The tebbetey is a fur-lined hat worn in the winter.

Kyrgyz identity is often expressed with a calpac. Kyrgyz cherish it and call it a "holy cap". When taken off, it is hung up or put on a quilt or pillow. People never casually throw it down, step on it or play with it—actions which are regarded as taboo or near-taboo breaches of etiquette. The calpac has a long history. There is even a sage associated with it. In ancient time, according to one legend, there was a wise, smart and brave Kyrgyz king, who found that various colored caps, horses and clothing affected his army. Before a major campaign, he ordered his ministers to prepare unified caps for his army and civilians in 40 days. In accordance with the king’s criteria the caps had to be bright like a star, beautiful as a flower, white as an iceberg and green as a summer mountain, plus repel rain, snow, wind and sand at the same time. After 39 days, 39 ministers were killed because they could not produce a hat that pleased the king. At last, the wise daughter of the 40th minister devised the calpac and the king was satisfied. And the cap was passed to now. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

See Separate Article KYRGYZ CLOTHES factsanddetails.com

Kyrgyz Culture

The Kyrgyz are renowned singers and dancers. The songs with rich content include lyrics, epics and folk songs. Kyrgyz paintings and carvings feature animal horn patterns for decoration on yurts, horse gear, gravestones and buildings. The Kyrgyz like bright red, white and blue colors. So their decorative art is always brightly colored and eye-pleasing, and full of freshness and vitality. [Source: China.org |]

Kyrgyz folk songs and ballads to are richly lyrical, expressing joy, sorrow, injustice and loss. The song types range from traditional folk songs to lullabies to wedding songs. They even have short ditties that they sing to departing guests and to their animal flocks. Kyrgyz musicians use many kinds of unusual instruments. For example, the three-stringed lute-like instrument popular in Kyrgyz music, the komuz, is uniquely Kyrgyz in origin. Every Kizilsu Kyrgyz learns to play the komuz from early childhood.

Many poems, legends, proverbs and fables have been handed down among the Kyrgyz for centuries. The epic, "Manas," is virtually an encyclopedia for the study of the ancient Kyrgyz. It has 200,000 verses describing, through the deeds of several generations of the Manas family, the bravery and courage of the Kyrgyz in resisting plunder by the nobles of Dzungaria and their aspirations for freedom. It is also a mirror of the habits, customs and ideas of the Kyrgyz of the time. |

Manas: the Great Kyrgyz Epic

Manas reader in Kyrgyzstan

The “The “Manas” is heroic Kyrgyz epic with over 200,000 lines long. Regarded by the Kyrgyz as both its Bible and it Iliad, this narrative poem is not only a literary treasure, but also a encyclopedia to study the history and culture of the Kyrgyz. Traditionally, whenever Kyrgyz people had free time or at events weddings and festivals they got together—sometimes a small group, sometimes a crowd of hundreds, even thousands of people—they would recite of sing the “Manas”. In China it is regarded as one of the three great long epics along the Tibetan epic, “King Gesar” and the Mongolian epic Jiangger. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The ”Manasi” is the version of The Manas read in China. It has eight volumes and 200,000 lines. Each volume is named after the central character in it. They are: I) “Manasi”, II) Semaitaiyi, III) Saiyitieke, IV) Kainainimu, V) Saiyite, VI) Asilebaqia—Biekebaqia, 7) VII Sumubilaike and VIII) Qiketaiyi. The whole epic is named after the first character “Manas”. The epic topic describes how eight generations of King “Manas” descendants unified all the Kyrgyz tribes together to defend against invasions from other groups. With help from their friends and comrades, “Manas” and his offspring punished traitors, outwitted demons, assisted the weak and the poor, and above all defended the Kyrgyz people. Similar to other epics, the “Manas” is filled with scenes of wars against different enemies. The epic demonstrates the strong spirit of the Kyrgyz as they forged their identity and strove for for national independence. It also describes the life and society of the Kyrgyz people ancient times and in the Middle Ages. ~

See Separate Article MANAS factsanddetails.com

China Tries the Claim The Manas as Its Own

In China, the “Manasi” (“Manas”) is claimed to be one of the three great long epics along with the Tibetan epic, “King Gesar” and the Mongolian epic “Jiangger.” In 2018, the Poly Theater in Beijing hosted a stage version of “Manas". Some have seen these labels and efforts as an attempt by the Chinese to claim the story as their own. Bruce Humes wrote in Altaic Storytelling: “A large-scale, colourful rendition of the Kyrgyz epic Manas was staged in March 2018 in Beijing’s ultra-modern Poly Theater. This performance came just two days after President Xi Jinping, speaking at the People’s Congress, cited the Manas and two other non-Han-Chinese works, the Tibetan-language King Gesar and the Mongol-language Jiangger .showing their importance in the Party’s current multiethnic-is-good narrative. [Source: Bruce Humes, Altaic Storytelling, April 12, 2018]

“Experts don’t agree on the epic’s history, but it has undoubtedly been around in oral form for at least several centuries. Composed in Kyrgyz, a language spoken by the Kyrgyz people in northwest Xinjiang and neighboring Kyrgyzstan, it was not available in full in Kyrgyz script until the mid-90s, and only then translated into Chinese. The master manaschi, Jusup Mamayrecited his 232,500-line version for prosperity (and was sentenced to a long stint of “reform through labor” during the Cultural Revolution for his efforts).

“For some time now, scholars at the prestigious Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the state media have been busy “re-packaging” these three epics in a way that emphasizes their Chineseness, while playing down their non-Han origins. The trio, which includes the Mongolian epic Jangar, are now frequently referred to as “China’s three great oral epics” , despite the fact that all three were composed in languages other than Chinese by peoples (Kyrgyz, Mongols and Tibetans) in territories that were not then firmly within the Chinese empire.

“Media coverage of the Poly Theater production of Manas arguably takes this repurposing one step further. Entitled Manas Epic Reenacted on the Opera Stage , in the first two-thirds of the widely shared article, there are no mentions whatsoever of the word “Kyrgyz,” or references to the Kyrgyz people or language, or their homelands in Xinjiang or Kyrgyzstan. The opera, it reports, “recreates the magnificent, relentless struggle of the Chinese people for freedom and progress . . .”

Granted, “Kyrgyz” does appear three times in the remaining third of the article, but it appears at the bottom in what is essentially a sidebar that describes the storyline of the opera; far from the eye-catching photos of the opera characters in exotic garb and the opening text that follows those colorful vignettes. Nowhere in the article is it noted that the epic was composed in a Turkic language (Kyrgyz) or that it is still considered by Kyrgyz speakers — on both sides of the border — to be the very incarnation of their identity as a nation.

Kyrgyz Camel Hide Crafts

The Kyrgyz have a long association with hairy, double-humped Bactrian camels. Camels have not only been important transportation tools for long journeys, migrating and carrying stuff, they also supply meat, milk, wool and fur. Kyrgyz people have developed their own set of crafts to process camel hide. Camel hide is very strong, hard and wear-resistant. Wise and experienced Kyrgyz herdsmen utilize different parts of camel hide to make various beautiful, light, flexible bowls, kettles and pails, which are well-suited to the livestock breeding life. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Camel hide bowls are made of camel knees. To make them: 1) cut out the whole camel knees; 2) shell them into bowl shape, removing outsider hair and inside flesh and fat; 3) sand them to a round shape with sand and put into a dry place; 4) when they are dry, pour out the sound and cut the knees to size of common bowls; 5) two pieces of camel skin are sewn together and cut into a round shape to make bowl props. 6) At this stage the bowls take their shape and the finishing process begins. 7) At first, the bowls are sanded and kneaded continuously until they are smooth; 8) ghee is smeared on them and heated on a fire for days to let the ghee be absorbed into the camel hide. As the knees of living camels are constantly touching sand, they are very hard and friction-proof. Consequently, camel-knee bowls are very hard and easy to clean. They are as beautiful and useful as modern porcelain bowls. ~

Camel hide kettles are made of hump hide. To make them: 1) cut off the two humps and remove the flesh and fat; 2) then cut into the shape of a kettle, which is large at the bottom, small at the top and robe-like in the middle. 2) Two pieces of hide of this shape are sewn together and filled with sand to maintain their kettle-like shape, then they are dried. 3) After a half-dry, the two pieces of hide are separated and some alkali, sour milk and corn flour are added and rolled together in order to let them rise. After 15 days, the remains of flesh and fat are soft and can easily be removed. Then the two hide pieces are sewn together again, carefully with embroidered patterns on the seams, face and mouth. It is said, that kettle like these were originally prepared for soldiers to wash their hands and faces. ~

Camel hide pails are made of camel neck. To make them: 1) a whole camel neck is cut, with the flesh and bone removed to make a hide tube. 2) Outside hair and inside fat are scraped carefully. 3) One end of the tube is sewn together. 4) The sewn tube is filled with sand and smashed, and the whole tube is set in the sun until it is half dry. 5) The sewn end is opened and the tube shape is restored. 6) The sand is poured out, ghee and fat are applied to inside of the pail wall. 7) The pails are put over smoke and fire for some time. 8) A round camel hide is used to make the bottom of the pail. 9) The tube and bottom are sewn together, and holes are made in the pail wall to fasten a rope. The result is a light and durable pail that is well made and can hold five or six liters of water or milk. ~

The history of making Kyrgyz hide containers and utensils is very long. However, many traditional hide crafts have disappeared as cheap modern alternatives have arrived on the scene. Still camel hide bowls, kettles, pails and other items are still sought after as they are unique; they have positive distinguishing features; and often are so beautifully crafted they can be considered works of art. ~

Kyrgyz Horse-Mounted Sports and Buz Kashi

Festivals often feature long distance horse races, acrobatic horse riding by both men and women and horse-mounted sports such as buz kashi and udarysh—horse-mounted wrestling in which the contestants are stripped to the waist and slathered with sheep fat and try wrestle each other to the ground. Other popular horse-mounted sports played by the Kyrgyz include chabysh (a 20 to 30 kilometer horse race), jumby atmai (horse-mounted archery), and tipin enemei (picking up coins on the ground while riding at a full gallop).

Kes kumay (“kiss the maiden”) is a popular sport in Kyrgyz and Kazakh areas. A man on horseback races across a meadow and chases after a girl on horseback and tries to kiss her while both are riding at a full gallop. The girl does everything she can to escape. If the man fails he gets chased and whipped. If he succeeds, he is regarded as a true jigit (master of horsemanship and embodiment of male virtue). It has traditionally been believed that no woman could resist falling in love with such a man. The sport began as an alternative to bride abduction.

Buzkashi (literally "goat dragging" in Persian) or kokpar is a Central Asian sport in which horse-mounted players attempt to drag a goat or calf carcass toward a goal. A competition of power and wits, it has traditionally been the most popular sport among the Kyrgyz.. Buz kashi tests people's boldness and their skill at horse training as well as riding. Generally it is played at festivals, important ceremonies and large weddings. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

See Separate Articles: TRADITIONAL SPORTS IN KYRGYZSTAN factsanddetails.com and BUZ KASHI factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBCand various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022