MONGOL NOMADIC LIFE

Mongols have traditionally grown up on horseback and horses played an important part in their life. Mongols used to prove their worth by showing good horsemanship, archery and wrestling skills. A red or green waistband a with flint steel, snuffbox and knife in an ornate sheath for cutting meat were accessories common to all men and women. [Source: China.org |]

In pastoral areas, beef, mutton and dairy products are the staple food, while in the farming areas, people like to eat grain. Tea is indispensable. Dried cow dung is a common cooking fuel.Mongol herdsmen used to live primarily in felt yurts (See Below). After the mid-20th century, as more and more herdsmen ended their nomadic life and settled down, they began to build yurt-like houses of mud and wood and one-storied houses, each with two or three rooms like those in other parts of the country. Today, most Mongols live in modern apartment blocks in urban development centers. |

In China, collectivization was first introduced in the late 1950s. In the early 1980s it was rejected in favor of the responsibility system, which extended to both farmer and herder long-term contracts to use the land. Under the "job responsibility system," the earnings of the herdsmen and peasants are linked with the amount of work they put in, has been implemented in the region. According to the Chinese government: This has further fired the enthusiasm of the Mongol people and this has brought tremendous changes to the life of the Mongol people. In the old days, the majority of them lived in hunger, being deprived of the essential means of life such as an old yurt. Today they have well-furnished yurts with clean beds and new quilts. Sewing machines, radios, TV sets, telescopes and cream separators are no longer novelties to the ordinary Mongol herdsmen. Many new houses with paned windows have been built in the Mongol settlements. |

See Separate Article GER LIFE factsanddetails.com NOMAD LIFE factsanddetails.com NOMAD MIGRATIONS factsanddetails.com HORSEMAN TENTS, FOOD AND DRINK factsanddetails.com INNER MONGOLIA: ITS HISTORY, PEOPLE, RESOURCES AND ECONOMY factsanddetails.com MONGOL NOMADIC LIFE factsanddetails.com ; MONGOL ANGER, ACTIVISM AND PROTESTS IN MAY 2011 factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Mongols: A History” by Jeremiah Curtin Amazon.com; “Plateau Women in Transition: The Mongolians” by Deng Qiyao Amazon.com; “The Land of the Camel: Tents and Temples of Inner Mongolia” by Schuyler Cammann (1951) Amazon.com; “Wolf Totem” by Jiang Rong (Novel) Amazon.com; “Wolf Totem” (Film) Amazon.com; “China's Last Nomads: History and Culture of China's Kazaks” by Linda Benson and Ingvar Svanberg Amazon.com; “Winter Pasture: One Woman's Journey with China's Kazakh Herders” by Li Juan, Nancy Wu, et al. Amazon.com; “Exile from the Grasslands: Tibetan Herders and Chinese Development Projects” by Jarmila Ptáčková Amazon.com; “Ecological Migrants: The Relocation of China's Ewenki Reindeer Herders” by Yuanyuan Xie Amazon.com; “In the Circle of White Stones: Moving through Seasons with Nomads of Eastern Tibet” by Gillian G. Tan and Stevan Harrell Amazon.com; “Nomads of Western Tibet: the Survival of a Way of Life” by Cynthia M. Goldstein, Melvyn C. & Beall Amazon.com

Animal Herding in Inner Mongolia

William Jankowiak, Ian Skoggard, and John Beierle wrote: Pastoralism is a household enterprise: everyone in a household, including adult men, women, children, and elderly engage in some kind of production activity. Large families also have wider social contacts that can and do provide economic support. Access to markets, social and health benefits, water resources, emergency pasture and veterinary services have transformed patterns of mobility and residence. Inner Mongolia herders move less distances and there is less effective management of the common grazing land. The environmental risks remain. There are acute natural hazards such as animals disease, fire, fluctuations in rainfall, and quality of forage impact the herders well being. In the past, this risk was spread across the collective, today each household is responsible for its own survival. Herders, therefore, are more vulnerable to social and biophysical shifts in the environment. [Source: William Jankowiak, Ian Skoggard, and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

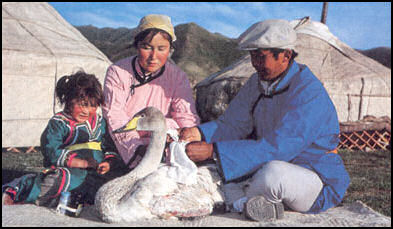

Mongol nomads

The traditional grazing system protected the principle of an open range. Though land was formally under the control of feudal lords, customary law gave common herders unlimited rights to graze their herds wherever they pleased within the boundaries of the banner. Recent research on indigenous forms of land utilization finds that they do not lead to range degradation. Privatization has transformed pastoral and farming way of life. Pastures are allocated to individual households, which has led to a decreased mobility and an increase in pasture degradation.

Up to 1940 land tenure was feudal and livestock managed by family groups. The livestock industry was collectivized in the early 50s — families kept their own subsistence stock (about 25 percent of total livestock units). In the early 1980s, the collective system was rejected in favor of an individual centered responsibility system, which extended to both farmer and herder long-term contracts to use the land. In 2000, livestock and land use polices were under different administrative units.

Mongol Herders and Their Horses

Zhang Zixuan wrote in the China Daily: “Buyandalai, 48,a herder of Hexigten Banner, Inner Mongolia autonomous region, says he owes his life to his horse. But for its furious kicking to alert him to two wolves closing in on him on a full moon night in the open in 1985, he would never have been able to flee the scene in time. Buyandalai points out that Mongols have been identified as "an ethnic group on horseback" since the time of Genghis Khan (1162-1227). [Source: Zhang Zixuan, China Daily, December 6, 2010]

"The horse is a totem of the Mongol people," Buyandalai told the China Daily but laments that they are fast losing their iconic status. The sight of thousands of galloping horses, a common one at the time of Buyandalai's father is fast becoming the stuff of fairytales. Living on the undulating Gungger steppe, Buyandalai still uses his horse as his means of transport, which he says is faster especially in winter.

But what he cares about much more is the cultural significance of the horse to his ethnic group. "Mongol culture is not just about singing songs and eating meat; it has got spirit," he says. "The Mongol horse defines who we are." The herder continues to own some 20 horses despite being fined more than 20,000 yuan ($3,000) between 2005 and 2009 by the local administration.

Decline of Pastoralism in Inner Mongolia

According to eHRAF: By the early 1990's the standard of living of the pastoralist had declined. Local herders believe they have been bypassed in Inner Mongolia's development that favors farmers and urbanites over herders. Herders were assessed with new kinds of taxes, experienced less profitable exchanges, and had to deal with an increase in animal thefts that cut into their income. By the late 1990s herding families preferred that their children move to the towns and cities to find better employment opportunities.[Source: William Jankowiak, Ian Skoggard, and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Constructing a yurt

The reform government has invested much less in animal husbandry than it has in crop cultivation and forestry. The expansion of peasant farming into the grasslands represents the final phase in the long history of the central government's efforts to sedentarize, control, and monitor the mobile herding populations on its periphery. One consequence of this trend has been an increase in the difference between poor and rich herders with the wealthier one-fifth of rural households now controlling five times the wealth owned by the bottom one-fifth. The reappearance of the patron-client relationship among herders in Inner Mongolia suggests the reappearance of a nascent class structure.

Mounting demographic pressures have impacted the availability of viable grassland. The vegetative yield of China's grasslands has shrunk by half, while the number of livestock has quadrupled. Since the 1960's, the rate of desert expansion in the Ordos region exceeds the natural rate of expansion over the previous 2,000 years. The process of land degradation has eliminated large tracts of usable pasture and has contributed to uncomfortable spring dust storms.

Horsemen in Western and Northern China

The Mongols, Turks, Huns, Tartars and Scythians are the best known of horsemen groups that have roamed the steppes of Central Asia and the ones that were most successful in expanding beyond their native realm and impacted the worlds they touched. The Mongols created the largest empire the world has ever known.

Horseman groups originated about 2,500 years ago and continue in various forms today. Throughout their long run they have maintained many of the customs, characteristics, martial arts and methods of organization that evolved millennia ago such spending living in yurt-style tents, drinking fermented mare’s milk, fighting from horseback and creating art forms that celebrate horses and animals of the steppe.The home range of the early horsemen, the Eurasia steppe, is vast area of land that extends from the Carpathian mountains in Hungary to eastern Mongolia.

About 40,000 ethic Kazakh, Mongol and Kyrgyz nomads still roaming the grasslands. Authorities want them to settle down in permanent houses and are attempting to do this by fencing off grazing grounds and establishing permanent settlements. The Chinese see nomadism as inferior to farming and conventional livestock rearing.

In places where overgrazing is a problem fences have been put up and herders have been given plots of land to encourage to take good care of it. To reduce the number of animals the government is encouraging herders to cut the size of their flocks by 40 percent, relocate and stall-feed their animals. But herders are not so keen on these ideas. Animals have traditionally been a source of wealth and a kind of insurance for hard times.

Horses in Yiling region of Xinjiang

Some nomads like the idea. They want a high standard of living. Those that participate in the Chinese program are given 13 hectares of land, a four-room concrete house. One former nomad rents out three fourths of his land to a farmer who grows wheat and vegetables and cotton. With the rest of the land he grows food for his 200 sheep, 100 cows and 70 horses. Detractors argue the program will spoil ethnic identity and destroy the grasslands through overgrazing.

Kazahks, Kyrgyz, Mongols and Uighurs can easily communicate because their languages are so similar and often eat and party together. During social gatherings, women usually serve the meals but don't join the men while they are eating. They do join in for the after dinner sing and dancing. Permanent Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Mongol and Uighur homes are made of mud bricks covered with smooth mud "plaster." Red and black carpets with geometric designs cover the walls and floors. Most homes have kangs, a raised platform with yet more rugs where family eats, relaxes and sleeps under a heap of quilts. Kangs are heated in the winter. Meals are usually cooked over an open fire on a mud brick stove formed in the corner of the house.

Handful of Mongol Herders Live on in China

Few Mongols live as traditional horsemen and herders. Most made the move from yurts to brick homes decades ago and wear traditional robes only on special occasions. “Most of our people have moved away from the old way of life,” the Mongol punk-folk-singer Ilchi said, “After moving to the cities, many of us have gradually been subjected to a very strong cultural invasion by an oppressive culture...Everyone surrounding you speaks Chinese,” Ilchi says. “No one speaks Mongol. If you don't speak Chinese, you can't survive. It's unavoidable. The Beijing government claims they are happier than they were before.

The Torgut Mongols remain nomadic. They herd sheep, some horses, cattle and camels in rich pastures of the Junggar basin, a region surround by tree-covered snow-capped mountains that are reminiscent of the Alps.

Elsewhere, Mongol culture lives among a dwindling number of people. Buyandalai, a herder of Hexigten Banner, Inner Mongolia, insists on living in a Mongol yurt with his wife when other herders are replacing their traditional dwellings with brick houses. He says there are less than 20 families in his banner who still live in yurts all year long like him. [Source: Zhang Zixuan, China Daily, December 6, 2010]

Altandelger lives in downtown Hexigten and spends most of his time making horse saddles, a craft declared a provincial-level intangible cultural heritage in Inner Mongolia. "A traditional Mongol saddle set takes more than one month to make," Altandelger told the China Daily. "It begins with a wood base, which is then covered with sharkskin or leather. Other accessories such as stirrups and silver decorations are added later." Although the horse is no longer the primary means of transport in the grasslands, making the saddle is an art that Altandelger wants to pass on.

Mongolian Herders and the Chinese Government

According to the e Human Relations Area Files:“In China, the weakened local government has largely rescinded responsibility for pastoral management to individual households, which makes it difficult to implement coordinated practices. In 1990, Shilingo league instituted a formal group called the HOT that was used to allocate grazing land. These changes have made kinship relations more economically vital than they were in the past, when members of the collective (negdel ) functioned as wage laborers. Today, pastoral households rely upon developed exchange networks (e.g., friends and kin) to supply goods and services.[Source: William Jankowiak and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Throughout much of the early twentieth century, the migration of Chinese peasants pushed the herders onto inferior pastureland. This led to periodic conflict. Today, many Han Chinese believe the state's affirmative-action policy provides Mongols with many benefits. The Mongols argue that the state has not provided enough benefits. Mongols tend to associate within their own community. Han-Mongolian friendships, as opposed to work related relationships, are the exception. Inner Mongolians also identify strongly with the Chinese state. For their part, they consider themselves to be members of an ethnic group as well as being Chinese citizens.

herder diorama

Resettling Mongol Herders

Since the early 1980s when Inner Mongolia, along with the rest of the nation, introduced the system of farmland quotas, the traditionally nomadic herdsmen have become settlers. In what has been described as one of the most ambitious attempts made at social engineering, the Chinese government spent 15 years resettling millions of pastoralists who once roamed China’s vast borderlands. Between the early 2000s and mid 2010s, Beijing said it had moved these herders, some of them nomads, into towns that provide access to schools, electricity and modern health care. This has also meant the grasslands are no longer grazed seasonally by rotation but intensely all-year round on the allotted lands. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 11, 2015]

Andrew Jacobs wrote in New York Times in 2011, “In Damao, those with money are encouraged to move into new apartment blocks on the outskirts of town. For now, they appear largely vacant, although a billboard near the entrance claims that 20,000 people have already moved into the 31 buildings. Those too poor to buy new homes rent cramped rooms in the town’s Mongol quarter, a grim, densely packed cluster of brick buildings. On a recent afternoon, Suyaltu and Uyung, the husband-and-wife proprietors of a small canteen called Friend of the Grassland, explained how they were forced to sell their pasture and a herd of 300 cows, sheep and horses in 2004. There are perks to the program, they said: subsidized school fees for their college-age daughter, a $2,775 annual subsidy and the advantages of living near medical clinics, shops and schools.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, June 1, 2011]

In 2015, Jacobs wrote: Official news accounts of the relocation rapturously depict former nomads as grateful for salvation from primitive lives. “In merely five years, herders in Qinghai who for generations roved in search of water and grass, have transcended a millennium’s distance and taken enormous strides toward modernity,” said a front-page article in the state-run Farmers’ Daily. “The Communist Party’s preferential policies for herders are like the warm spring breeze that brightens the grassland in green and reaches into the herders’ hearts.”

“Although policies vary from place to place, displaced herders on average pay about 30 percent of the cost of their new government-built homes, according to official figures. Most are given living subsidies, with a condition that recipients quit their nomadic ways. One herder told the China the family’s $965 annual stipend — good for five years — was $300 less than promised. “Once the subsidies stop, I’m not sure what we will do,” he said.

“Rights advocates say the relocations are often accomplished through coercion, leaving former nomads adrift in grim, isolated hamlets. In Inner Mongolia and Tibet, protests by displaced herders occur almost weekly, prompting increasingly harsh crackdowns by security forces. “The idea that herders destroy the grasslands is just an excuse to displace people that the Chinese government thinks have a backward way of life,” said Enghebatu Togochog, the director of the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, based in New York. “They promise good jobs and nice houses, but only later do the herders discover these things are untrue.”

Grievances play a role in social unrest, especially in Inner Mongolia and Tibet. Over the past few years, the authorities in Inner Mongolia have arrested scores of former herders, including 17 last month in Tongliao municipality who were protesting the confiscation of 10,000 acres. This year, dozens of people from Xin Kang village, some carrying banners that read “We want to return home” and “We want survival,” marched on government offices and clashed with riot police, according to the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center.

See Separate Articles RESETTLED TIBETAN HERDERS factsanddetails.com TIBETAN HERDERS AND NOMADS factsanddetails.com

Relocation of Nomads in Inner Mongolia

Andrew Jacobs wrote in New York Times, Uyung, 50, said that even when combined with the income from their restaurant, their soon-to-expire subsidy was not enough to sustain the family. Then there are other, less tangible downsides to the arrangement. “We feel lost without our herds and the grassland,” she said as her husband looked at his feet and dragged on a cigarette. “We discovered we are not suited to the city, but now we are stuck.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, June 1, 2011]

Chen Jiqun, director of Echoing Steppe, an organization that works to protect Inner Mongolia’s grasslands, told the New York Times the benefits of ecological migration were questionable. For one, he said, a healthy pasture depends on the hooves of grazing animals to grind up manure. “Otherwise it just blows away and the land loses its fertility,” he said. In a report issued last December, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Olivier De Schutter, criticized China’s nomad resettlement policies as overly coercive and said they led to “increased poverty, environmental degradation and social breakdown.”

“In Xilinhot, a coal-rich swath of Inner Mongolia, resettled nomads, many illiterate, say they were deceived into signing contracts they barely understood. Among them is Tsokhochir, 63, whose wife and three daughters were among the first 100 families to move into Xin Kang village, a collection of forlorn brick houses in the shadow of two power plants and a belching steel factory that blankets them in soot. In 2003, he says, officials forced him to sell his 20 horses and 300 sheep, and they provided him with loans to buy two milk cows imported from Australia. The family’s herd has since grown to 13, but Tsokhochir says falling milk prices and costly store-bought feed means they barely break even. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 11, 2015]

“An ethnic Mongolian with a deeply tanned face, Tsokhochir turns emotional as he recites grievances while his wife looks away. Ill-suited for the Mongolian steppe’s punishing winters, the cows frequently catch pneumonia and their teats freeze. Frequent dust storms leave their mouths filled with grit. The government’s promised feed subsidies never came. Barred from grazing lands and lacking skills for employment in the steel mill, many Xin Kang youths have left to find work elsewhere in China. “This is not a place fit for human beings,” Tsokhochir said.

“Not everyone is dissatisfied. Bater, 34, a sheep merchant raised on the grasslands, lives in one of the new high-rises that line downtown Xilinhot’s broad avenues. Every month or so he drives 380 miles to see customers in Beijing, on smooth highways that have replaced pitted roads. “It used to take a day to travel between my hometown and Xilinhot, and you might get stuck in a ditch,” he said. “Now it takes 40 minutes.” Talkative, college-educated and fluent in Mandarin, Bater criticized neighbors who he said want government subsidies but refuse to embrace the new economy, much of it centered on open-pit coal mines. He expressed little nostalgia for the Mongolian nomad’s life — foraging in droughts, sleeping in yurts and cooking on fires of dried dung. “Who needs horses now when there are cars?” he said, driving through the bustle of downtown Xilinhot. “Does America still have cowboys?” Experts say the relocation efforts often have another goal, largely absent from official policy pronouncements: greater Communist Party control over people who have long roamed on the margins of Chinese society.

Herders Forced to Give Up Horses Because of Concerns About Overgrazing

As the authorities step up efforts to save the grasslands from over-grazing they are urging and coercing herders to give up the horse. In 2003, the local steppe administrative bureau began to restrict the number of horses based on the yield of grass in the allotted grasslands. Horses that exceed the number attract a fine of 180 yuan ($27) each. And in 2008, Buyandalai and other herders of Hexigten Banner were given notice that all large herds of horses in the banner would have to be sold within three years. [Source: Zhang Zixuan, China Daily, December 6, 2010]

According to the Statistic Yearbook of Inner Mongolia, in 1975 there were 2.39 million horses in the autonomous region. That figure had fallen to 914,000 in 2002. And in 2010, there are less than 500,000 horses, decreasing constantly at the rate of 5.5 percent every year. "Horses create little economic value and have lost their practical use as tools of transport and production," Hobiskhaltu, deputy director of Hexigten Banner told the China Daily. "It's only a matter of time before they disappear...The steppes can only support so much grazing and we have to consider the balance of the ecosystem. We don't want to take the horses by force so fines offer the best deterrent." But herders vehemently disagree. Oljei, a 62-year-old herder who sold all his 2,000 goats in 2002 in response to the call to protect the steppes says, "Unlike goats, horses don't destroy the grass roots. It's unfair to attribute the deterioration of the grasslands to horses." He points out that much greater damage has been done by human exploitation through mining and tourism. [Source: Zhang Zixuan, China Daily, December 6, 2010]

Altandelger, 60, who grew up on horseback, says horses are intelligent creatures who can warn herders about impending danger and foul weather. "When they stop eating and move their ears, it means something dangerous is nearby," he says. "And if they keep on yawning, it indicates good weather the next day.""Horses only eat the grass tip so they need to move around. Free-range breeding allows grass sufficient time to grow, and this helps sustain the ecology," says Ortnastb, from the Inner Mongolia University in Hohhot, capital of the autonomous region. "When horses are fenced in, they die, and so do the steppes."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, BBC, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022