RESETTLED TIBETAN HERDERS

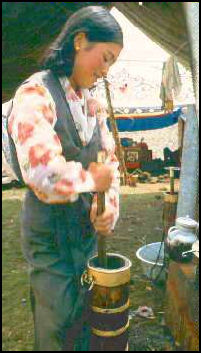

Making butter tea

At great expense the Chinese government has resettled hundreds of thousands of Tibetan nomads and herders in what is billed an effort to improve the lives of the nomads and protect rivers and save grassland from overgrazing. More than two million Tibetans, most of them pastoralists, were relocated between 2006 and 2013, according to Human Rights Watch, as well as hundreds of thousands of nomadic herders in the eastern part of the Tibetan plateau such as in Qinghai province. The human rights group said in a report the aim of the resettlements is in part to help economically, but also to combat separatist sentiment “and is designed to strengthen political control over the Tibetan rural population”. [Source: Reuters, June 27, 2013; Maureen Fan Washington Post, September 28, 2008]

Che government says it has moved more than 500,000 nomads and a million animals off ecologically fragile pastureland in Qinghai Province. As of the late 2000s, more than 100,000 families in Qinghai Province — almost half the Tibetan population there — had been resettled. In 2007 officials said they would spend $80 million to settle most of the nomads by the end of 2009. In 2008, the Gansu Province government said it would spend $189 million to relocated 74,000 nomads there, most of them in Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Region

Nomads have been resettled on farming communities while their land has “literally been taken from under their feet.” The impact of programs on nomads varies. In some cases the nomads are encouraged to give up their animals completely and take jobs or work as farmers and do things like sell horseback rides to tourists for $4 a an hour. In other cases they keep their animals behind fences in areas near the settlements and move between winter and summer locations. In yet other cases some family members live in settlements while other family members move with their animals and return home every 10 days or so.

See Separate Article TIBETAN HERDERS AND NOMADS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Exile from the Grasslands: Tibetan Herders and Chinese Development Projects” by Jarmila Ptáčková Amazon.com; “Tibetan Nomads: Environment, Pastoral Economy, and Material Culture” by Schuyler Jones and Ida Nicolaisen Amazon.com; “Agro-Animal Resources of Higher Himalayas” by Deepa H. Dwivedi & SAnjai K. Dwivedi & Sandhya Gupta Amazon.com ; “Tibetan Pastoralists and Development: Negotiating the Future of Grassland Livelihoods” by Andreas Gruschke and Ingo Breuer Amazon.com; “Nomads of Western Tibet: The Survival of a Way of Life” by Melvyn C. Goldstein and Cynthia M. Beall Amazon.com; “In the Circle of White Stones: Moving through Seasons with Nomads of Eastern Tibet” by Gillian G. Tan and Stevan Harrell Amazon.com; “Nomads in Eastern Tibet: Social Organization and Economy of a Pastoral Estate in the Kingdom of Dege” by Rinzin Thargyal, Toni Huber Amazon.com; “Tibetan Nomads” by Daniel Miller Amazon.com; “Tibetan Nomad: Memoir of a Tangled Hair Woman” by Norzom Lala Amazon.com

Resettled Tibetan Herders in Qinghai and Gansu

Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “Along the road near the town of Madoi are two rows of newly built houses. This is a resettlement village for Tibetan nomads, part of a massive and controversial program to relieve pressure on the grasslands near the sources of China's three major rivers — the Yangtze, Yellow, and Mekong — where nearly half of Qinghai Province's 530,000 nomads have traditionally lived. Tens of thousands of nomads here have had to give up their way of life, and many more may follow. The subsidized housing is solid, and residents receive a small annual stipend. Even so, Jixi Lamu, a 33-year-old woman in a traditional embroidered dress, says her family is stuck in limbo, dependent on government handouts. "We've spent the $400 we had left from selling off our animals," she says. "There was no future with our herds, but there's no future here either." Her husband is away looking for menial work. Inside the one-room house, her mother sits on the bed, fingering her prayer beads. A Buddhist shrine stands on the other side of the room, but the candles have burned out.” [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

Reporting from Madoi Town, Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: “If modern material comforts are the measure of success, then Gere, a 59-year-old former yak-and-sheep herder in China’s western Qinghai Province, should be a happy man. In the two years since the Chinese government forced him to sell his livestock and move into a squat concrete house here on the windswept Tibetan plateau, Gere and his family have acquired a washing machine, a refrigerator and a color television that beams Mandarin-language historical dramas into their whitewashed living room. But Gere, who like many Tibetans uses a single name, is filled with regret. Like hundreds of thousands of pastoralists across China who have been relocated into bleak townships over the past decade, he is jobless, deeply indebted and dependent on shrinking government subsidies to buy the milk, meat and wool he once obtained from his flocks. “We don’t go hungry, but we have lost the life that our ancestors practiced for thousands of years,” he said. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 11, 2015]

“New Madoi Town, where Gere’s family lives, was among the first so-called Socialist Villages constructed in the Amdo region of Qinghai Province, an overwhelmingly Tibetan area more than 13,000 feet above sea level. As resettlement gained momentum a decade ago, the government said that overgrazing was imperiling the vast watershed that nourishes the Yellow, Yangtze and the Mekong rivers, China’s most important waterways.

Relocation of Herders and Nomads in China’s Frontiers

In what the New York Times described as one of the most ambitious attempts made at social engineering, the Chinese government spent 15 years resettling millions of pastoralists who once roamed China’s vast borderlands. Between the early 2000s and mid 2010s, Beijing said it had moved these herders, some of them nomads, into towns that provide access to schools, electricity and modern health care. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 11, 2015]

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: Official news accounts of the relocation rapturously depict former nomads as grateful for salvation from primitive lives. “In merely five years, herders in Qinghai who for generations roved in search of water and grass, have transcended a millennium’s distance and taken enormous strides toward modernity,” said a front-page article in the state-run Farmers’ Daily. “The Communist Party’s preferential policies for herders are like the warm spring breeze that brightens the grassland in green and reaches into the herders’ hearts.”

“Although policies vary from place to place, displaced herders on average pay about 30 percent of the cost of their new government-built homes, according to official figures. Most are given living subsidies, with a condition that recipients quit their nomadic ways. One herder told the China the family’s $965 annual stipend — good for five years — was $300 less than promised. “Once the subsidies stop, I’m not sure what we will do,” he said.

“For the Han Chinese majority, the people of the grasslands are a source of fascination and fear. China’s most significant periods of foreign subjugation came at the hands of nomadic invaders, including Kublai Khan, whose Mongolian horseback warriors ruled China for almost a century beginning in 1271. “These areas have always been hard to know and hard to govern by outsiders, seen as places of banditry or guerrilla warfare and home to peoples who long resisted integration,” said Charlene E. Makley, an anthropologist at Reed College, in Oregon, who studies Tibetan communities in China. “But now the government feels it has the will and the resources to bring these people into the fold.”

“Although efforts to tame the borderlands began soon after Mao Zedong took power in 1949, they accelerated in 2000 with a modernization campaign, “Go West,” that sought to rapidly transform Xinjiang and Tibetan-populated areas through enormous infrastructure investment, nomad relocations and Han Chinese migration. The more recent “Ecological Relocation” program, started in 2003, has focused on reclaiming the region’s fraying grasslands by decreasing animal grazing.

Chinese Take on the Relocation of Tibetan Herders

In July 2011, the China Daily: After living in mud-brick huts for generations, people in Bangoin county, in the north pasturing area of the Tibet autonomous region, moved into new concrete houses with the help of the government's Comfortable Housing Project. Local resident Dondrup told China Daily that poor Tibetan herdsmen had to live in black tents made from yak hair. "The nomadic life sounds exotic and even romantic to travelers, but Tibetans in our county are drifting in a harsh environment where the average altitude is 4,900 meters and the temperature is merely zero degrees," she said. "Everybody wants to live in safe buildings with heating, running water and electric lights." [Source: Dachong and Peng Yining, China Daily, July 21, 2011]

So far, 80 percent of the 2,314 residents in Dondrup's village have moved into their new homes, and by the end of 2015, all residents in Bangoin county will be living in safe and comfortable houses. According to the local authority, each household has been provided with a subsidy of more than 20,000 yuan ($3,090) to build a new house. People can choose the location of their houses to watch their cattle and meadow.

According to a report by the Tibet autonomous region, since the government launched the Comfortable Housing Project in 2006, a total of 1.4 million farmers and herdsmen in 274,800 families have moved to safe and comfortable housing with per-capita living space of 24 square meters. "Many Tibetans, especially farmers and herdsmen in remote areas, used to live in poor conditions, and the Comfortable Housing Project greatly improved their livelihood," said Qiangba Puncog, head of the standing committee of the autonomous region's people's congress. He said efforts have also been made to promote construction of water, power and gas supplies, roads, telecommunications, radio and TV stations and post offices in agricultural and pasturing areas.

Paldrond, a 46-year-old Tibetan in Gongbo'gyamda county, along with 136 people from her village, moved to a new site in 2006. They used to live in mud-brick houses on a high cliff and it would take them more than one hour to climb down to the road leading to the nearest town. All of the villagers were suffering from Kashin-Beck disease, a painful joint disease probably caused by the doubtful water source in the village. Paldrond's finger joints are swollen. She said the pain prevented her from doing heavy farm work. "I'm glad that my children are living in a safe concrete house with a clean water supply," she said. The county government covered most of the construction expense and provided running water and electricity, according to Zhao Wei, the county official.

“Now Paldrond and her four children live beside a highway where she can sell herb-medicine and farm products. Her family's income increased to 70,000 yuan in 2010 from 20,000 yuan in 2005. The new house can be constructed and designed by local Tibetans, said Zhao, in order to keep the Tibetan lifestyle. Most locals choose to decorate their new houses with Buddhist wall paintings and traditional iron shard stoves. "Black tents and a nomadic lifestyle were a part of Tibetan culture, but they are fading as more people settle in concrete houses," said Shilok Rigzin, a Tibetan from Nagqu prefecture. "The government should improve people's livelihood and respect tradition as well."

Problems with the Relocation of Herders in China

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: The policies to relocate herders, “ based partly on the official view that grazing harms grasslands, are increasingly contentious. Ecologists in China and abroad say the scientific foundations of nomad resettlement are dubious. Anthropologists who have studied government-built relocation centers have documented chronic unemployment, alcoholism and the fraying of millenniums-old traditions. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 11, 2015]

“Chinese economists, citing a yawning income gap between the booming eastern provinces and impoverished far west, say government planners have yet to achieve their stated goal of boosting incomes among former pastoralists. The government has spent $3.45 billion” on the relocation of 1.2 million herders in the mid 2010s” but most of the newly settled nomads have not fared well. Residents of cities like Beijing and Shanghai on average earn twice as much as counterparts in Tibet and Xinjiang, the western expanse that abuts Central Asia. Government figures show that the disparities have widened in recent years.

“Nicholas Bequelin, the director of the East Asia division of Amnesty International, said the struggle between farmers and pastoralists is not new, but that the Chinese government had taken it to a new level. “These relocation campaigns are almost Stalinist in their range and ambition, without any regard for what the people in these communities want,” he said. “In a matter of years, the government is wiping out entire indigenous cultures.” A map shows why the Communist Party has long sought to tame the pastoralists. Rangelands cover more than 40 percent of China, from Xinjiang in the far west to the expansive steppe of Inner Mongolia in the north. The lands have been the traditional home to Uighurs, Kazakhs, Manchus and an array of other ethnic minorities who have bristled at Beijing’s heavy-handed rule.[Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 11, 2015]

“Chinese scientists whose research once provided the official rationale for relocation have become increasingly critical of the government. Some, like Li Wenjun, a professor of environmental management at Peking University, have found that resettling large numbers of pastoralists into towns exacerbates poverty and worsens water scarcity. In published studies, she has said that traditional grazing practices benefit the land. “We argue that a system of food production such as the nomadic pastoralism that was sustainable for centuries using very little water is the best choice,” according to a recent article she wrote in the journal Land Use Policy.

Social Unrest Over the Relocation of Herders

Jarmila Ptackova, an anthropologist at the Academy of Sciences in the Czech Republic who studies Tibetan resettlement communities, told the New York Times the government’s relocation programs had improved access to medical care and education. Some entrepreneurial Tibetans had even become wealthy, she said, but many people resent the speed and coercive aspects of the relocations. “All of these things have been decided without their participation,” she said. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 11, 2015]

“Rights advocates say the relocations are often accomplished through coercion, leaving former nomads adrift in grim, isolated hamlets. In Inner Mongolia and Tibet, protests by displaced herders occur almost weekly, prompting increasingly harsh crackdowns by security forces. “The idea that herders destroy the grasslands is just an excuse to displace people that the Chinese government thinks have a backward way of life,” said Enghebatu Togochog, the director of the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, based in New York. “They promise good jobs and nice houses, but only later do the herders discover these things are untrue.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 11, 2015]

Grievances play a role in social unrest, especially in Inner Mongolia and Tibet. Since 2009, more than 140 Tibetans, two dozen of them nomads, have self-immolated to protest intrusive policies, among them restrictions on religious practices and mining on environmentally delicate land. The most recent one took place on Thursday, in a city not far from Madoi. Over the past few years, the authorities in Inner Mongolia have arrested scores of former herders, including 17 last month in Tongliao municipality who were protesting the confiscation of 10,000 acres. This year, dozens of people from Xin Kang village, some carrying banners that read “We want to return home” and “We want survival,” marched on government offices and clashed with riot police, according to the Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center.

Nomads’ New Village

In a newly-created town called “Nomads’ New Village” former nomads live in brick-and-tile houses that are considerably warmer and more comfortable than nomads tents. Generally children have better access to education, families have better access to health care and people are easier to manage in terms of offering heating in bad weather and informing them of new programs and offering medicines and new technology for themselves and their animals. For those that keep their animals it is easier to keep an eye on them and prevent them from being stolen. [Source: Reuters, June 27, 2013; Maureen Fan Washington Post, September 28, 2008]

A government researcher working there told the Washington Post, ‘some people who are flexible sell their livestock and buy vehicles to do business such as transportation and tourism. Definitely, settling down will affect their nomadic culture, but from the aspect of social development settling down is using an advanced lifestyle to replace a backwards lifestyle.” Many who have settled down keep their tents as a reminder of the old days. Most remain loyal to the Dalai Lama and show no sign of compromising that loyalty. Some aid workers say if the resettled nomads need anything it is more temples to fulfill heir spiritual demands. A typical herder that once had 600 sheep and 150 yaks and ate meat every meal now lives in a concrete house and receives a $1000-year stipend and get by making deliveries with tractor for $1 to $3 a day and get by on noodles and fried dough.

Reporting from a Tibetan area in Sichuan, Hannah Beech wrote in Time: “The Tibetan plateau’s lunar landscape is littered with clusters of houses the Chinese government built for nomads. Yet like some American real estate developments abandoned during the subprime-mortgage crisis, many of these houses in Gardze are empty. Few Tibetan nomads want to live in Chinese houses. The government worker does not understand it. They are nice houses, he says, much warmer in winter than a yak-wool tent. “If we were to give the Tibetans independence,” he says, “they would starve and have no clothes on their back.”

Problems Suffered by Resettled Nomads

Many nomads are illiterate and there are few jobs in the resettlement towns. Some have returned to herding because there is nothing else for them to do but even doing that is hard because they gave up their large herds when they were resettled have to start from scratch with just a handful of animals. In any case, many want their children to go to school and achieve a better life. In places where the nomads have been force to give up their animals rates of alcoholism are high. In other places poor planing has left residents without reliable water add power sources. Those that move to cities are often out hustled by the more aggressive and entrepreneurial-minded Han Chinese for jobs and businesses.

In many cases children stay in the towns and settlements with their grandparents while the parents tend animals in some far off place. One 64-year-old Tibetan woman told the Washington Post that she appreciated the subsidized house she received but she missed the old days because “Life was harder but at least we were together. Now we old people have to take care of ourselves.”

Researchers also worry that by resettling the nomads, valuable, ecological knowledge and animal husbandry skills will be lost. Diseases spread easier among animals and people living more close together. Because they are stuck in one place the animals eat less nutritious grass than they would if they were more free ranging. Researchers say the social fabric of nomadic life has broken down to some extent. Liu Shurun of the Inner Mongolia Normal University told the Washington Post, “Before nomads were quite selfless. It was very important to help each other when they moved around in groups. But now each family settles in one place with their own plots of land, and they don’t rely on each other so much.”

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: Gere, the 59-year-old herder, said he had scoffed at government claims that his 160 yaks and 400 sheep were destructive, but he had no choice other than to sell them. “Only a fool would disobey the government,” he said. “Grazing our animals wasn’t a problem for thousands of years yet suddenly they say it is.” Proceeds from the livestock sale and a lump sum of government compensation did not go far. Most of it went for unpaid grazing and water taxes, he said, and about $3,200 was spent building the family’s new two-bedroom home. Many of the new homes in Madoi lack toilets or running water. Residents complain of cracked walls, leaky roofs and unfinished sidewalks. But the anger also reflects their loss of independence, the demands of a cash economy and a belief that they were displaced with false assurances that they would one day be allowed to return. Gere recently pitched his former home, a black yak-hide tent, on the side of a highway as a pit stop for Chinese tourists. “We’ll serve milk tea and yak jerky,” he said hopefully. Then he turned maudlin as he fiddled with a set of keys tied to his waist. “We used to carry knives,” he said. “Now we have to carry keys.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 11, 2015]

Criticism of the Resettled Nomad Program in Tibet

Critics of the nomad resettlement program see the program is as way for Beijing to control the Tibetan population by keeping an eye on them and countering the influence of the Dalai Lama. Communist Party chief Zhang Qingli wrote in a party journal the “peace and contentment” that nomads derive from their improved housing “is the fundamental condition for us holding the initiative in the struggle against the Dalai clique.” The riots in March 2008 have stepped the relocation of the nomads,

Addressing some of the criticism Tanzen Lhundup of the Beijing-based China Tibetology Research Center, said nomadic culture will not disappear. “First, not all the nomads are being moved, just some of them. Second, nobody is stopping them from carrying on their culture, their religion, their customs. They can still sing and dance.”

In June 2013, New York-based Human Rights Watch appealed to the Chinese government to end what it called forced “mass rehousing and relocation” of ethnic Tibetans. A report by the human rights group said Chinese authorities threw lives of nomads into disarray by denying them rights to forcibly relocating them with insufficient compensation, sub-par housing and lack of help in finding jobs. “The scale and speed at which the Tibetan rural population is being remodelled by mass rehousing and relocation policies are unprecedented in the post-Mao era,” said Human Rights Watch China Director Sophie Richardson. “Tibetans have no say in the design of policies that are radically altering their way of life, and - in an already highly repressive context - no ways to challenge them.” [Source: Reuters, June 27, 2013]

Reports: “‘They Say We Should Be Grateful’: Mass Rehousing and Relocation in Tibetan Areas of China” by Human Rights Watch hrw.org/ ; New York Times article of the Human Rights Watch report: nytimes.com ; for download, 31 photos accompanying the report can be found here ; and a short video here youtube

Woeser on the Resettlement of Tibets Nomads

The Tibetan activist wrote: In August 2012, I drove back to Lhasa in the car of my friends and spent one night in Gormo, a man-made city with a very short history. Five years ago, I also stopped here to visit fellow Tibetans living in the outskirts of the city in the Gobi desert. The word “living” is not really accurate, they were migrants who had “been moved” there, approximately 200 to 300 households; all of them had lived in “the first county of the Yellow River”, in Yushu Prefecture, Chumarlep County and were then moved to this place, arranged to live in a migrant village in barrack-like housing. This many Tibetans who used to be herdsmen, keeping livestock, had been forced to integrate in what is referred to as a modern environment. Their language, food and lifestyles underwent great changes, not to mention that there was no place to practice religion in this new place; it becomes clear that this kind of “integration” was extremely passive and painful. [Source: “The ‘Mani Stones’ in an ‘Environmental Migrants Village’” By Woeser, High Peaks Pure Earth, July 1, 2013, translated by High Peaks Pure Earth from a blogpost by Woeser written on September 27, 2012 for the Tibetan service of Radio Free Asia and published on her blog on January 31, 2013 ]

“I will never forget the sad conversation that I had with these Tibetan migrants. I asked: “When you moved here did your mountain deity move with you?” My Tibetan friends, dressed in cheap western suits, lowered their heads and said: “How is that possible? We abandoned our deities, we abandoned our livestock, and all that for 500 Yuan per month.” But in fact, it was not at all because of this little bit of money that these Tibetans abandoned their ancestors and deities of their homeland. In 2003, the Chinese government persisted in claiming that the grasslands of the Tibetan plateau were degenerating, caused by Tibetan herdsmen’s several thousand years of nomadic lifestyles, so they launched a massive, never seen before project, moving Tibetan herdsmen from the sources of the Yangtze, Yellow and Mekong River to the fringes of towns and cities. To put it positively, they tried to give the Tibetan grasslands some time off to breathe. But the result is probably the elimination of nomadic lifestyles, which is such an important part of Tibetan culture.

“According to reports, this project, which is called “Three Rivers Area National Nature Reserve Environmental Migrants Village Project”, migrated 16,129 families, 89,358 people, affecting over 10 towns and counties and autonomous prefectures. Of course, all those people were Tibetan herdsmen, described as “leaving their horsebacks and flocks of sheep”, these people actually transformed into “‘outsiders’ living at the edge of cities”. When I was in their newly built migrants village back then, what made me feel particularly desolate was that in this place there was not a single Mani Lhakhang or stupa for Tibetans to practice Buddhism; neither were there any resident monks who could have helped these Tibetan migrants overcome the emptiness in their hearts.

“When I entered the migrants village once again last year, I realised immediately that on the once spacious and empty Gobi desert had appeared many tent-shaped sacred flag masts, massive in size and extending seemingly endlessly into the distance, fluttering in the evening wind. Near those flags was a purple-red house, in its centre there was probably a big prayer wheel, existing to comfort those that went to turn it. Opposite to this, there was a building that looked a little bit like a monastery, which was separated from the rows of migrant housing by a road.

“I stopped a man who was passing by and got to know that he had been living here for six years but had still not got used to this place. Every year, each household only got about 5000 Yuan, which was nowhere near enough. He was sometimes able to find a job at a building site, digging holes or removing stones, which would earn him no more than 20 or 30 Yuan per day. “Since the monastery is here, I feel much more at ease”, he said turning his head towards the purple-red building that was disappearing in the dim light of the night. “We raised money ourselves to build it, what we are worried about now is whether the government will approve it, they should agree I think, but I really don’t know, I just don’t know.” After he had explained all the possibilities of what may happen, I felt full of sympathy.

“I also went to visit a family; a woman dressed in Tibetan clothes was raising three children, all of them were going to school, they could speak Mandarin, their clothes also resembled those of Chinese kids from the city, only that they were wearing protection cords given to them by lamas around their necks. The woman said that her husband could drive, but they still didn’t have enough money to buy meat and real butter, so they had to buy artificial butter to make butter tea.

“When I was leaving the migrants village, I once more looked at the field of sacred banners and was surprised to see that underneath them there were large mani stones; but they were not real stones, they were turned-over pool tables on which there had been engraved the six words of truth (Om Mani Padme Hum). I suddenly understood what had been going on. The migrants, facing the difficulty of having endless time but not knowing what to do, spent their time drinking, gambling and playing pool and then the pool table had somehow turned into a mani stone. Maybe this happened because of the enlightenment of lamas who passed on the Buddhist teachings, or maybe it happened more because of the strong belief of these Tibetans who had never wanted to abandon their homelands and deities; and only this is what really matters, it indicates the revival and continuation of vitality and the spirit to not perish.”

Image Sources: Purdue University, University of Washington, Snowland Cuckoo, Mongabay, Tibet Train

Text Sources: Primary Source: "At Home with Tibetan Nomads" by Melvyn Goldstein, National Geographic, June 1989 ♠; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022