TIBETAN NOMADS

Tibetan herder with a yak Nomadic herders in Tibet are known as drokpa. They make up about 25 percent of Tibetans in Tibet. In some Tibetan counties they make up 90 percent of the population. Herding families tend to be very poor, with a family typically getting by on an income of between $100 and $300 a year. Money is earned by trading animals for grain or selling them or their meat for money. Some traders and pilgrims are regarded as nomads. [Primary Source: "At Home with Tibetan Nomads" by Melvyn Goldstein, National Geographic, June 1989 ♠]

Generally, Tibet can be divided into farming areas and pastoral areas. Those living in pastoral areas are called nomads or pastoralists. These people sometimes build houses as home bases, for their old folks and for storage. Otherwise, they live the nomad life and in traditional nomadic tents. Nomads are people who graze animals within particular places. Those in Tibet are specially adapted towards high altitudes. Their primary aim is to feed their animals with the best available grass and foods. They have traditionally worn thick clothes, lived in tents and moved from place to place in order to feed the animals. Their income is derived from their animals: namely from selling their meat and skins, which they have traditionally had to do in towns and cities. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org]

Stephen McDonell of the BBC wrote: There was a time here when tribal Tibetans roamed across a vast dramatic landscape with no specific place to call home. For generation after generation they had lived as nomads, sleeping where they made camp. They kept their livestock moving, chasing the fresh pastures that became available as the seasons changed. The limits of their territory were identified by mountains and rivers, and their nomadic existence permeated all aspects of their culture. [Source: Stephen McDonell, BBC, August 18 2016]

Tibetan nomads have a lot in common with Mongolian nomads. Tibetan nomad culture is quickly disappearing as more Tibetans each year are being relocated off of the grasslands.

See Separate Article RESETTLED TIBETAN HERDERS factsanddetails.com ; many articles TIBETAN LIFE factsanddetails.com TIBETAN PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Center for Research on Tibet case.edu ; BBC pictures news.bbc.co.uk ; Nomad portraits asianart.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Nomads of Western Tibet: The Survival of a Way of Life” by Melvyn C. Goldstein and Cynthia M. Beall Amazon.com; “Agro-Animal Resources of Higher Himalayas” by Deepa H. Dwivedi & SAnjai K. Dwivedi & Sandhya Gupta Amazon.com ; “In the Circle of White Stones: Moving through Seasons with Nomads of Eastern Tibet” by Gillian G. Tan and Stevan Harrell Amazon.com; “Nomads in Eastern Tibet: Social Organization and Economy of a Pastoral Estate in the Kingdom of Dege” by Rinzin Thargyal, Toni Huber Amazon.com; “Tibetan Nomads” by Daniel Miller Amazon.com; “Tibetan Nomad: Memoir of a Tangled Hair Woman” by Norzom Lala Amazon.com; “Tibetan Nomads: Environment, Pastoral Economy, and Material Culture” by Schuyler Jones and Ida Nicolaisen Amazon.com; “Exile from the Grasslands: Tibetan Herders and Chinese Development Projects” by Jarmila Ptáčková Amazon.com; “Tibetan Pastoralists and Development: Negotiating the Future of Grassland Livelihoods” by Andreas Gruschke and Ingo Breuer Amazon.com;

Places Where Tibetan Nomads Live

There are an estimated 2 million Tibetans in the Tibet Autonomous Region and other Tibetan areas that practice some form of nomadism. For centuries these nomads have ranged across the grasslands of the Tibetan plateau with their grazing herds of sheep, cattle, goats and yaks.

Many of the inhabitants of the highland plateau are nomadic shepherds and yak and horse breeders. Southern Tibet — where the climate is less hostile and where there are a number of valleys where barley and other crops are raised — is main agricultural area and where most Tibetans in Tibet live. Most of the Tibetans that live there are farmers. Farmers and herders have traditionally exchanged products at annual and biennial markets, fairs and horse festivals. Herders in remote areas usually make grain-getting expeditions in the fall.

About half a million Tibetan nomads live on the Chang Tang, a huge, remote, 15,000-foot plateau rimmed by mountains. Tens of thousands of other Tibetan nomads can be found in other remote regions of Tibet. The nomads in the Phala region of the Chang Tang live in small camps consisting of two to eight tents. They herd yaks, sheep and horses, and reside throughout the year at sites ranging from 16,000 to 17,500 feet, which makes them the highest known resident native population in the world.♠

Most herders and nomads live in Nagqu prefecture — a 4,500-meter-high, 446,000 square kilometer region on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau that accounts for 37 percent of Tibet Autonomous Region. Nagqu has the largest pastoral area and the highest productivity in the region. Breeding livestock accounts for 70 percent of the prefecture’s income and more than 90 percent of Nagqu residents make their living from it. Nagqu accounts for one third of the Tibet Autonomous Region’s animal husbandry.

History of Tibetan Nomads

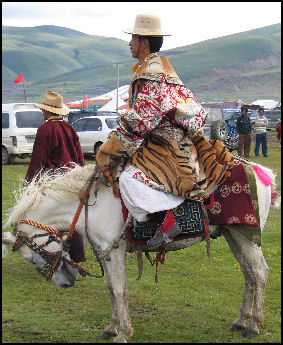

Tibetan horseman in full regalia

Tibetan nomads have traditionally lived beyond the reach of the government. After the Chinese came to power in China in 1949 Tibetan nomads continued to live pretty much as they had for hundreds of years. After the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1959, the Communist government began imposing restrictions on the nomad's "primitive" lifestyle.

In the 1960s and 70s, many nomads had their possessions confiscated and were put in communes. The nomads who weren't forced into communes often had their animals confiscated and were not given a place to live. Many however managed to tough it out on the plateau with a few goats. Some families survived for years on nothing but goat milk and a little money they earned doing odd jobs for the communes.♠

During the Cultural Revolution, the Communists not only confiscated animals from Tibetan nomads but also took their jewelry (ripping earrings right out of their ears in some cases), their robes and blankets they used to keep warm, and the yak tents that were their homes. One family with nearly 1,400 animals, had nearly everything they owned confiscated. "They left us only one pot, some barley grain, and a little tsampa," one family member said, "We were stunned. Our whole life's wealth was eliminated in minutes. We didn't know how were going to survive."♠

Tibetan nomads on the plateau tried to hold off the Red Guard and the People's Liberation Army, but the nomad's matchlock weapons were no match for the automatic weapons of the Chinese. Today, nomads live under a system almost the same the one that existed during feudal times, except that the taxes go to Chinese government instead of lamas. ♠

Tibetan Nomad Tents and Possessions

Many nomads live in four-sided or eight-sided tents made from black yak hair or wool and held up with wooden poles. There is a slit to let out smoke. In the old days some had a bearskin front. Sometimes Tibetans live in yurts.

Every nomadic family has several yak hair tents that can be easily dismantled and moved. In hot weather, the loose wool weaves let wind blow through, keeping the air fresh and cool inside. On cold weather, the tent weaves become tight, keeping wind, cold and rain out. [Source: Chloe Xin, Tibetravel.org ]

There are two kinds of tents: black yak wool tents and white cloth tents. People in pastoral areas are used to living in yak wool tents. In agricultural areas some people still use Tibetan cloth tents. The black yak tents generally have no adornment, but whenever people raise a tent, they hang prayer flags to bless the grassland and their animals and other living creatures with enough food. The black yak tent is viewed as a huge sky mastiff (sky spider) resting in the vast plain. At the top of the tent is a smoke escape symbolizing the highest mountain’s tallest gate.

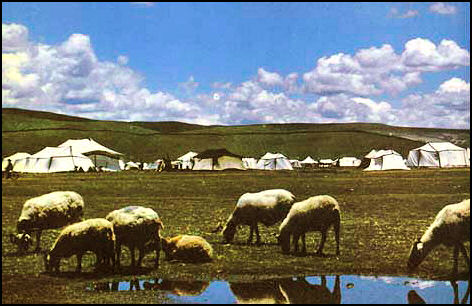

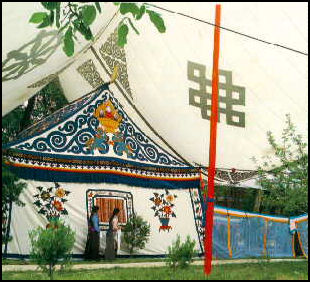

The smaller and elegant white tents have traditionally been used by Tibetan girls. Pastoral people generally have a couple of these lighter white cloth tents. They are good for traveling and multitudes of them are set up at religious or racing gathering. Elders, teens, and guests usually stay in these kind of tents. The fireplace is usually outside the tent. There are big hexagonal tents, well decorated with religious signs, set up around monasteries or for the use of religious occasions.

Nomad tents and other possessions are carried by horses or yaks or by truck. Inside the tents is an altar dedicated to various Buddhist deities and protector gods. Next to the altar is a box for jewelry and other valuables. Other possessions include a cooking stove, sheepskin sleeping mats and yak-hair blankets. Because there is so little rain they often sleep outside. A nasty dog is kept around to keep away predators.

Summer camp

Making and Erecting Tibetan Nomad Tents

To make a black yak wool tent, people use yak wool to make big ropes first, and then tie the ropes together. A good size tent, which covers about 28 square meters, requires about 90 kilograms of wool. The tent is square at the base with a window at the top that let smoke out and sunlight in. On snowy and rainy days, the window can be shut. The front part of the tent is split into two pieces to make a door. There are generally no beds, chairs or furniture inside the tent. People sit on carpets and cushions. In the middle of the tent, a stive is set up. Behind is yak dung fuel.

Nomads traditionally have spun the yak hair into threads and weave it into striped cloth, then they sewed the cloth into a square tent of 2 pieces, which are joined by 10 ouches or so to form a completed tent. This kind of tent is usually square-shaped supported by 8 upright pillars. On one end, more than 10 strings of yak hair are tied to the pillars at the top of the tent, while the other end is tied to the poles about 3 meters away, making the tent flat and firm. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

To pitch a tent, people first use sticks to make a frame as high as 2 meters, and then they cover it with black yak felt, leaving a chink in the middle with a 15 centimeter width and 1.5 meter length. This split lets smoke out and sunlight in. As well, the 4 sides of the tent are secured to the ground with yak wool ropes.

Inside a Tibetan Nomad Tents

A Tibetan tent is about 20 square meters in area and 1.7 meters high with a ventilating slit at the top to let out smoke and heat when opened and to keep the tent warm and protected from wind and rainwater if covered. In the front of the tent there is a string tied to the door curtain which can be drawn to control the opening. On hot days, the door curtain can be propped up to let air in making the inside cool and comfortable. The yak hair material is instrumental to the success of the tent, making it wearable, thick, and durable enough against strong winds and snowstorms. Meanwhile, it is also convenient to be dismantled, put up, and removed, fitting for nomadic life. [Source: Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/]

Inside, people build a 50 centimeter high wall made of grass-earth blocks, earth blocks, or stones, on which barley, butter bags, or yak dung (used as fuel) are usually placed. The tent is typically poorly furnished, without many household items. In the middle (near the door) of the tent, an earthy fireplace is set up, and behind is a worshipping place equipped with Buddha statues. People often spread a sheepskin rug on the floor for rest or sleep.

The tent is divided into two quarters. Males occupy the left half, and females the right half. The inner part of the left side is the worshiping place equipped with Buddha statues, scripts, and lamps. The right side is for utensils and food storage. Outside the tent, sometimes people build a wall of sod or dung to guard the animals or protect them against cold wind.

Adults and children share the space inside the tent. They usually each have their own area and gather around a fire made of yak dung and juniper branches in an open hearth the middle of the tent. Yak cheese hangs from the walls above piles of heavy blankets.

Tibetan Nomad Life

Nomads live a hard life. They often eat little more than old hard cheese, dried raw meat, butter, yoghurt, sour milk and black tea. Normally they don't like taking showers. Sometimes their boots and straps are made of wild asses skin tied together with thread from the tendons of wild animals. Family members take of tame yaks, sheep and goats. They endure frigid cold, storms and blizzards. They erect votive cairns to honor mountain gods and venerate strange spirits that dwell in the lakes, rivers and mountains. Often when they die their bodies are taken to a mountain, and left to the wolves and vultures.

Most nomads are only nomads in the summer. In the winter they live in valleys in houses with wooden beams and earthen floors and pens or shelters for their animals. An increasing number have access to electricity. Some get electricity from small generators or solar panels. A typical three-generation nomad family with nine members has 70 yaks and 200 sheep and makes about $6,000 from selling animals.

The staples of the nomad diet are tsampa (roasted barley flour), and yak butter tea. Peasants sometimes ground the barley by pouring it into a funnel and crushing it into flour with a small millstone turned by water in a stream. Barley is often cooked on sand to keep it from scorching.Tibetan nomads who live above 15,000 foot can not grow barley. To obtain the grain they generally trade salt taken from around lakes with sheep and yak caravans that carry barley up from elevations. The water in the lakes of the Tibetan plateau is usually too salty too drink, therefore nomads always camp near a spring.♠

Anthropologist Melvyn Goldstein was impressed by the efficiency of Tibet's nomads. "They perform their tasks with very little wasted motion," he said. "When goats are milked, for example, a group of 30 or so animals is tied together and when the milking is done the animals are released with a simple pull on the rope. The milk itself is made into yoghurt, butter and cheese."

Nomads have to deal with cold weather and lots of walking. One Tibetan woman recalled that when she was a child her brothers would wrap her in their coats when she got cold and on long treks her father would carry her when her legs became weary.

On the life of young woman from a herding family, Annie Gowen wrote in the Washington Post, “When she was growing up, the local school taught classes in Mandarin, not Tibetan, so she received only rudimentary schooling at home. Her family, nomadic herders, could not travel from village to village without permission. They dared not speak the Dalai Lama’s name — even when they were alone in their tent of yak hide. They assumed their cellphone calls were monitored. [Source: Annie Gowen, Washington Post, October 19, 2014]

Tibetan Nomad Society

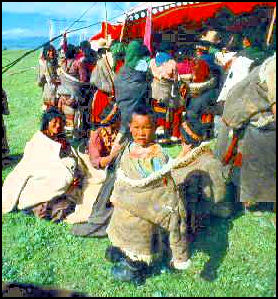

Nomads typically live in groups of 10 to 25 families, with each family living in a four-sided yak hair tent. Sometimes newlyweds live in small subsidiary tents. The tents are usually set up a considerable distance from one another so that each family has enough land to graze their animals. The descions to move on is made by all the families in the group.

Women usually stay close to camp doing various chores like weaving blankets and making butter while the men graze the animals. In the autumn when the animals are fattened up, the nomads head to markets, cities or trading areas to sell or trade their animals for supplies to keep them going through the winter and the entire year.

Nomad marriages are often worked out with the help of matchmakers who arrange meetings for young men and women from different groups. If a couple likes each other they meet with each other when they can over a long period of time and exchange gifts. The actual marriage ritual is a feigned kidnap attack, with the friends and family of the groom trying to help the groom abduct the bride and the friends and family of the bride reigning resistence, sometimes for several days before inviting the groom’s group for a feast and the allowing the bride to be taken away.

Nomads, Hunting and Livestock

Nomads typically raise yaks, goats and sheep and migrate between their winter homes in the valleys and highland pastures in the summer. They typically spend two thirds of the year in the valleys. Often the summer pastures are no more than 40 miles away from the their valley homes. Most nomads tend their flocks from horseback or on foot. Some do it by bicycle or motorcycle. The tents and other supplies are transported on the backs of yaks or on trucks.

Animals can survive in the Chang Tang during the summer even if the rainfall is poor but they need to build up a layer of fat if they are to survive the winter without supplemental fodder. As is true with other nomadic people like the Masai in Africa and the Sami (Lapps) in Scandinavia, animals are a sign of wealth for nomadic Tibetans.♠

A typical nomad has 50 yaks, 300 sheep and six horses. Some herds of sheep extend for more than a mile. Nomads say their way of life is much easier than farming. "The animals reproduce themselves," one woman said, "they give milk and meat without or doing anything. So how can you say our life is hard?" To keep the Chang Tang from being overgrazed a "pasture book" is kept collectively by the nomads to determine how many animals can graze a specific pasture.

Yaks are the most valuable animals. Seven goats or six sheep usually equal one yak. Nomads used to be required to sell certain numbers of animal to government agencies at a certain price. By the late 1980s they were selling their animals at market prices.

According to the Chinese government: Animal husbandry is the main occupation in Tibet where there are vast expanses of grasslands and rich sources of water. The Tibetan sheep, goat, yak and pien cattle are native to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. The yak is a big and long-haired animal, capable of with-standing harsh weather and carrying heavy loads. Known as the "Boat on the Plateau," the yak is a major means of transport as well as a source of meat. The pien cattle, a crossbreed of bull and yak, is the best draught animal and milk producer. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Tibetan nomads have traditionally hunted animals such as antelopes, blue sheep and gazelles. To hunt these animals nomadic hunters use dogs and matchlock rifles, 18th-century weapons that are so heavy and have so much kick they need a brace to keep them in place. The firing mechanism on a matchlock is a wick with a flint striker, which ignites the powder in the gun. "It is only accurate up to a hundred feet," a hunter said, "and it takes very long to fire...By the time I have done everything, the sheep would be long gone. That is why we use our dogs; they tilt the odds in our favor."♠

Journey to a Nomad Camp

“Today Nagqu sits on modern Highway 317, the northern branch of the Tea Horse Road,” Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic. “All signs of the former trade route have vanished, but just a day's drive southeast, temptingly close, are the Nyainqentanglha Mountains, where the original trail once passed. I am captivated by the possibility that back in the deep valleys Tibetans might still ride their indefatigable horses along the original trail. Perhaps, hidden in the vast hinterland, there is even still trade along the road. Then again, maybe the trail has vanished as it did in Sichuan, wiped out by howling wind and tumbling snow.” [Source: Mark Jenkins, National Geographic, May 2010]

“One rainy black morning halfway through the festival, while the police are looking the other way, Sue and I slip off in a Land Cruiser to find out what has happened to Tibet's Tea Horse Road. We race all day on dirt roads, grinding over passes, almost rolling on steep slopes. We don't stop at checkpoints, and we creep right past village police stations. By nightfall we reach Lharigo, a village between two enormous passes that once served as a sanctuary along the Gyalam. Surreptitiously, we go door-to-door looking for horses to take us up to 17,756-foot Nubgang Pass. There are none to be found, and we're directed to a saloon on the edge of town. Inside, Tibetan cowboys are drinking beer, shooting pool, and placing bets on a dice game called sho. They laugh when we ask for horses. No one rides horses anymore.”

“Outside the saloon, instead of steeds of muscle standing in the mud, there are steeds of steel: tough little Chinese motorcycles decorated like their bone-and-blood predecessors — red-and-blue Tibetan wool rugs cover the saddles, tassels dangle from the handlebars. For a price, two cowboys offer to take us to the base of the pass; from there we must walk.”

“We set off in the dark the next morning, backpacks strapped to the bikes like saddlebags. The cowboys are as adept on motorbikes as their ancestors were on horseback. We bounce through black bogs where the mud is two feet deep, splash through blue braided streams where our mufflers burble in the water. Up the valley we pass the black tents of Tibetan nomads. Parked in front of many of the yak hair tents are big Chinese trucks or Land Cruisers. Where did nomads get the money to buy such vehicles? Certainly not from the traditional yak meat-and-butter economy.”

“It takes five hours to cover the 18 miles to Tsachuka, a nomad camp at the base of the Nubgang Pass. The ride thoroughly jars our spines. The cowboys build a small sagebrush campfire and, after a lunch of yak jerky and yak butter tea, Sue and I set off on foot for the legendary pass. To our delight, the ancient path is quite visible, like a rocky trail in the Alps, winding up meadows speckled with black, long-horned yaks. After two hours of hard uphill hiking, we pass two shimmering sapphire tarns. Beyond these lakes, all green disappears and everything turns to stone and sky. Mule trains of tea stopped crossing this pass over a half century ago, but the trail had been maintained for a thousand years, boulders moved and stone steps built, and it's all still here. Sue and I zigzag through the talus, along the walled path, right up to the pass.”

“The saddle-shaped Nubgang Pass has clearly been abandoned. The few prayer flags still flapping are worn thin, the bones atop the cairns bleached white. There is a silence that only absence can create...In my imagination I see a mule train of a hundred animals plodding up toward us, dust swirling around their hooves, loads of tea rocking side to side, the cowboys alert for bandits waiting in ambush on the Nubgang Pass. Our motocowboys are waiting for us the next morning when we return from the pass. We saddle up and begin the long ride out, bumping and bashing down glacial valleys.”

Visit to a Tibetan Nomad Tent

Mark Jenkins wrote in National Geographic, “At midday we stop at two black nomad tents, surrounded by neat stacks of yak dung. A large solar panel hangs on each tent, and parked in the grass are a truck, a Land Cruiser, and two motorcycles. The nomads invite us in and offer cups of scalding yak butter tea.” [Source: Mark Jenkins, National Geographic, May 2010]

“Inside the tent, an old woman is twirling a prayer wheel and mumbling mantras, a young man is cooking in a shaft of light, and a few middle-aged men are sitting on thick Tibetan rugs. Through sign language and a pocket dictionary, I ask the men how they can afford their vehicles. They grin wildly, but the conversation strays.

On his visit Brook Larmer wrote in National Geographic, “The nomads' tent is a pinprick of white against a canvas of green and brown. There is no other sign of human existence on the 14,000-foot-high prairie that seems to extend to the end of the world. As a vehicle rattles toward the tent, two young men emerge, their long black hair horizontal in the wind. Ba O and his brother Tsering are part of an unbroken line of Tibetan nomads who for at least a thousand years have led their herds to summer grazing grounds near the headwaters of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers.” [Source: Brook Larmer, National Geographic, April 2010]

“Inside the tent, Ba O's wife tosses patties of dried yak dung onto the fire while her four-year-old son plays with a spool of sheep's wool. The family matriarch, Lu Ji, churns yak milk into cheese, rocking back and forth in a hypnotic rhythm. Behind her are two weathered Tibetan chests topped with a small Buddhist shrine: a red prayer wheel, a couple of smudged Tibetan texts, and several yak butter candles whose flames are never allowed to go out. "This is the way we've always done things," Ba O says. "And we don't want that to change."

Tibetan Nomad Hardships

Weather, namely rain, determines whether nomads have a good year or a bad one. When the rainy season brings enough rain pastures are green and full of edible grass for the animals. In dry years and droughts there isn’t enough food for the animals. Winter storms can also be damaging. Freezing temperatures can kill sheep and a thick layer of hard snow or ice can make it difficult for the animals to forage. Ideally herders try to collect enough grass and hay for the animals to eat in the winter and keep them indoors in stalls

A long rainy season can cause trouble by making it difficult to dry yak dung, Many years a wet spring and summer portends snowstorms in the winter.

Deep snows and long periods of cold can kill large numbers of animals and force nomads into poverty. The winter of 1997-98 killed an estimated three million yaks, sheep and goats. In some areas herders lost as many as 40 percent of their animals.

The worst winter snows in 50 years occurred in 1996. An estimated 1.2 million yaks, sheep and goats’some 40 percent of the regions domesticated animals — were killed. About 80,000 Tibetan herders were affected. Piles of animals could be seen on the side of the roads and hungry, desperate people broke into cars of foreign tourist looking for food.

The herders often fed their own food to their animals to keep them alive when the weather is bad. After a terrible winter storm in the 1930s, an entire clan committed suicide at the base of Qilian Mountain.

Sleeping in the damp ground can make people sick. Many old people suffer from arthritis.

In open grazing areas livestock can be easily stolen.

Tibetan Nomads and the Modern World

Large tent

The Chinese government is urging nomads to settle in communities were they have access to housing, health care and other services — and are under government control. Some nomads have moved from yak skin tents into brick houses and sell "yak cashmere" sweaters, yak meat, bones (used for glue) and fur for a steady income. In some places, Nomads have been taught how to make the most of money earned from their resources and animals by, for example, not letting their animals go free to earn merit in their next life. One Chinese official told Reuters, "Many of these people have assets but they are still poor because they don't know how to use them. So we send people to teach them how to open their minds to a market economy."

In some parts of Tibet, nomads are encouraged to fence off their pastures to prevent overgrazing and erosion, switch from subsistence herding to industrial livestock production and use the latest animal husbandry technology. Nomad families that go along with the government’s wishes sign long-term contracts for state-owned land. The size of the plot is determined by the family’s size and the number of animals they have. They are given money for fencing and access to yak sperm banks. Nomads who don’t go along with the government’s wishes face fines. Many nomads and environmentalists object to the policy of using fences and industrial livestock methods, arguing the policy breaks down the centuries-old way of life of the nomads, cuts off their access to drinking water, blocks migration routes of wild animals, and may cause more environmental damage than just letting the animals roam.

Nomadic ways are blamed for overgrazing. Tanzen Lhundup of the Beijing-based China Tibetology Research Center, “Nomads are human beings — they also want to maximize their interest. It is impossible for them to protect the environment voluntarily. So they need guidance and control. In my opinion, the first step is control...If we don’t do this, the grasslands will disappear and the nomads will suffer. So in the end, as the Chinese saying goes, short-term suffering is better than long-term suffering.”

See Separate Article RESETTLED TIBETAN HERDERS factsanddetails.com

Nomadism in Modern China

Reporting from Aba, a Tibetan area in Sichuan, Stephen McDonell of the BBC wrote: We get up before the sun hits the grassland. There are villages nearby and these days — during the freezing winter months at least — most people here live in fixed dwellings. or much of the year, people have televisions, fridges and electrical lights. But when the summer comes they head for the hills — back to the land of their forebears. “Nomads here are nomads to the bottom of our hearts," Kalsang Gyatso tells us. "We lived like this from ancient times. Actually we don't like being in houses." [Source: Stephen McDonell, BBC, August 18 2016]

“We meet him and other family members rounding up their yaks and pushing them into a pen. Soon they, like all their neighbouring herdsmen, will follow the same route as every year and drive their livestock into the mountains where the grass hasn't been touched for months. “If we don't go to the summer grasslands and just stay in the winter fields there will be no food left for the yaks. When they have new grass to eat, our animals will grow fat and they'll produce enough milk." He also tells us that the summer pastures have medicinal flowers which the yaks need to eat in order to stay healthy.

“The Tibetans are on horseback, calling and whistling to keep their livestock moving. Some of the yaks carry the bedding they'll need upon arrival as well as other bits and pieces for camping. One young man speaks to us as he rides past. He says they must move now in order to make the most of new grass and provide for their families and that the dates for the journey are actually fixed by government regulations. I ask how he feels getting back to the old ways at least for a few months, expecting a description of the rich ancient culture again flowing through his veins. "I'm a little bit tired," he says.

“Next to Kalsang Gyatso's place runs a recently laid tar road and along it the sound of hundreds of hooves can be heard. The migration is on! Cars and trucks must part a sea of animals in order to get through. Most drivers just stop and wait for the beasts to pass. As we follow group after group heading further to the west we reach… a grassland adventure park. It is being built smack in the middle of the main migration route and has already been opened. Eventually this attraction will be able to handle thousands of tourists on any given day. We watch as yaks in their hundreds are pushed through the car park, under the main gate, past the turnstiles and soon they are surrounding the tourist buses carrying ethnic Han Chinese travellers in search of an awe-inspiring Tibetan experience. Eventually he, his family and 400 yaks pass the tourist park and the outer limit of modern existence.

“They arrive at the untainted expanse of the high mountain grasslands. Here there are no shops, no roads, no tourists, but there is the space of their ancestors. “When I make it here my mood is very good, exceptionally good," he tells us. "When city people come here they will also feel happy because of the fresh air and the smell of wildflowers. It's like a fairyland." They will stay here until September. They will walk with bare feet in order to preserve the flowers that their yaks need to eat. They will milk their animals to make butter tea and cheese. And when the weather starts getting cold, they'll head back down the mountain, to return again next year.

Nomad Tourism in China

Reporting from a tourist camp set up in the middle of nomad migration route Stephen McDonell of the BBC wrote: “We board one of the buses and speak to those taking photos of the Tibetans riding along outside. “Up here it's exactly the eating a mouthful of meat, drinking a mouthful of wine plateau feeling that I wanted," says one woman. “It feels like another world. I feel stronger about Tibetan culture because Tibetans are purer and lead a more simple life," says another and her friend nods. They seem to have genuine affection for the people who call this place home and inside the adventure park they will come into contact with the Tibetans who have been employed here. [Source: Stephen McDonell, BBC, August 18 2016]

“The herding communities, however, are divided about whether the explosion in tourist numbers is such a good thing. Even the Tibetans who have opened small guest lodges with areas for camping are worried that their once pristine environment is gradually being overrun. Tshe Bdag Skyabs has been travelling with his animals for two days. “On the one hand, people's incomes have increased and transportation is more convenient," he says. "But the environmental harm from development has been huge."

The Chinese government is teaching Tibetan villagers to speak Mandarin and helping herders and farmers turn their homes into hotels, in an effort to boost tourism and the region's income, AFP reported in June 2021, “The cultural degradation that is involved in this case of hyper-managed mass tourism spectacle is very worrying," Robert Barnett of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London told AFP. “It's hard to identify, though, since of course there is a benefit for Tibetans in that trade; what is harder to quantify is the damage." [Source: Matthew Loh, Business Insider, June 16, 2021]

Image Sources: Purdue University, University of Washington, Snowland Cuckoo, Mongabay, Tibet Train

Text Sources: [Primary Source: "At Home with Tibetan Nomads" by Melvyn Goldstein, National Geographic, June 1989 ♠; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022