INNER MONGOLIA

Inner-Mongolia INNER MONGOLIA is a Chinese province-like entity that shares the vast Gobi desert and an immense area of dusty grassland with the country of Outer Mongolia to the north. Traditionally inhabited by nomadic Mongolian tribesmen who lived in gers (circular tents also known as yurts), Inner Mongolia is a desolate place with burning hot summers, frigid winters and huge, springtime sand storms that send gravel flying and sandblast cars. The grasslands were home to wild camels and herd of horses, but these are largely gone. These days the Han Chinese outnumber the ethnic Mongolians 6 to 1 and most people live in settlements in houses with tile roofs and mud-walls. There is a lot of mining and many rare earths, minerals vital for many industries, are mined and produced in Inner Mongolia. Maps of Inner Mongolia: chinamaps.org

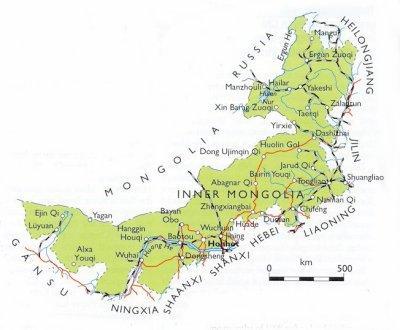

Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Nei Mongol Autonomous Region) is the third largest province-like area in China after Xinjiang and Tibet. It covers 1,183,000 square kilometers (457,000 square miles), more than a tenth of China's land mass and twice the size of California. The region is a sprawling area of pasturelands that sits atop northern China bordering the independent nation of Mongolia with an average elevation between 900 to 1,300 meters above sea level. There are vast tracts of excellent natural pastureland with numerous herds of cattle, sheep, horses and camels. The Yellow River Bend and Tumochuan plains, known as a "Granary North of the Great Wall," are crisscrossed with streams and irrigation canals. The Yellow River flows in southwestern Inner Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also has several hundred salt and alkali lakes and many large freshwater lakes, including Hulun Nur, Buir Nur, Ulansu Nur, Dai Hai and Huangqi Hai. Hohhot is the regional capital of Inner Mongolia. It is home to 2.6 million people , more than 87 percent of who are Han, the predominant ethnic group in China. Banner is a traditional term for county. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region was founded on May 1, 1947, as the earliest such establishment in China. It is not province but an autonomous region like Tibet theoretically set up to give the Mongolians some autonomy. Over time parts of Northeast China have been added to Inner Mongolia. Gansu province contains areas that have traditionally been part of Inner Mongolia. Like Chinese provinces, an autonomous region has its own local government, but an autonomous region — theoretically at least — has more legislative rights. An autonomous region is the highest level of minority autonomous entity in China. They have a comparably higher population — but not necessarily a majority — of the minority ethnic group in their name. Some of them have more Han Chinese than the named ethnic group. There are five province-level autonomous regions in China: 1) Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region for the Zhuang people, who make up 32 percent of the population; 2) Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Nei Mongol Autonomous Region) for Mongols, who make up only about 17 percent of the population; 3) Tibet Autonomous Region Autonomous Region (Xizang Autonomous Region) for Tibetans, who make up 90 percent of the population; 4) Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, for Uyghurs, who make up 45.6 percent of the population; and 5) Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, for the Hui, who make up 36 percent of the population. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Articles: CENTRAL ASIA, MONGOLIA Click Mongolia factsanddetails.com INNER MONGOLIA: ITS STEPPES, ETHNIC GROUPS AND NEOLITHIC CULTURES factsanddetails.com HOHHOT AND BAOTOU AREA OF INNER MONGOLIA factsanddetails.com ; GOBI DESERT SIGHTS IN INNER MONGOLIA AND GANSU IN CHINA factsanddetails.com MONGOLIANS, LANGUAGE, SHAMANISM AND CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com ; MONGOLIAN NOMADIC LIFE factsanddetails.com ; MONGOL CULTURE, MEDICINE AND SPORTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL MONGOLIAN MUSIC factsanddetails.com ; KHOOMI SINGERING: SINGING TWO TONES SIMULTANIOUSLY factsanddetails.com ; MONGOLIAN POP MUSIC AND DANCE factsanddetails.com ; MONGOL ANGER, ACTIVISM AND PROTESTS IN MAY 2011 factsanddetails.com

Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Center, an advocacy group in New York.

Good Websites and Sources on Minorities in Northern China: Nationalities in Northeast China kepu.net.cn ; Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Claude Pickens Collection harvard.edu/libraries ; Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Asia Times atimes.com

People of Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia mapInner Mongolia is one of China's largest and least densely-populated areas. Accounting for 12 percent of China's total land area but less than two percent of its population, it is an autonomous region like Tibet theoretically set up to give the Mongolians some autonomy. Inner Mongolia is inhabited by about 25 million people (2011), with Mongolians making up about 18 percent of the population and Han Chinese 80 percent. There are also some Huis, Manchus, Daurs, Ewenkis, Oroqens and Koreans. The population density of Inner Mongolia is around 20 people per kilometers. There are vast areas where no one lives.

According to the 2020 Chinese census the population of Inner Mongolia was around 24 million. There are about 3.5 million Mongolians living in Inner Mongolia (twice as many as in 1949) and 21.5 million Chinese (35 times as many as in 1949). About half of the Mongolians that live in China live in Inner Mongolia. The other half are scattered throughout northwest China. The population density of Inner Mongolia is 20 people per square kilometer. About 62 percent of the population lives in urban areas. Hothot is the capital with about 2 million people. Baotou is another large city with about the same population. Ethnic make up: Han: 79 percent; Mongol: 17 percent; Manchu: 2 percent; Hui: 0.9 percent; Daur: 0.3 percent. The official languages are Chinese and Mongolian, the latter written in the Mongolian script, as opposed to the Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet used in the state of Mongolia.

The population of Inner Mongolia was 24,049,155 in 2020; 24,706,321 in 2010; 23,323,347 in 2000; 21,456,798 in 1990; 19,274,279 in 1982; 12,348,638 in 1964; 6,100,104 in 1954. [Source: Wikipedia, China Census]

Following the founding of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, autonomous prefectures and counties were established in other provinces where Mongolians live in large communities. These include the two Mongolian autonomous prefectures of Boertala and Bayinguoleng in Xinjiang, the Mongolian and Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai, and the seven autonomous counties in Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu, Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning. Enjoying the same rights as all other nationalities in China, the Mongolians are joining them in running the country as its true masters.

Mongols (Mongolians) in China

Mongols (Mongolians) are a legendary ethnic group with a long history. For thousands of years, they roamed as nomads and conquerors across the vast steppes of Central Asia and Mongolia. In present-day China they have traditionally occupied the lands that stretches from the Great Wall in the south to the Gobi Desert in the north and from Xingan Mountains in the east to Henan Mountain in the west. On the places they live, an ancient Mongolian ballad goes: "The sky is gray, the open country is vast, grasses bend in the rustle of wind and flocks and herds come into the sight." Otherwise the land of the Mongols is known for its boundless pasture with the blue sky, white clouds, green fields, red flowers, flocks of sheep and tent camps heavy with the aroma of meat and milk. From here "the nationality on horseback" rode forth and shook heaven and earth and swept over Europe and Asia, fighting valiantly with clever tactics and tenacity. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~]

There are about 4.2 million Mongolians living in Inner Mongolia (about three times as many as in 1949) and 20 million Chinese (35 times as many as in 1949). About two thirds of the Mongolians that live in China live in Inner Mongolia. The other half are scattered throughout northwest China. Average disposable income of Inner Mongolia is around $7,000, one of the highest in China and on par with Beijing. Among the Chinese, Mongols have a reputation for being heavy drinkers. Some, Chinese say, drink heavily while they are working. Chinese police say that many prostitutes in China are from Inner Mongolia.

Mongols are the tenth largest ethnic group and the ninth largest minority in China. They numbered 6,290,204 and made up 0.45 percent of the total population of China in 2020 according to the 2020 Chinese census.

See Separate Article MONGOLS IN CHINA: THEIR LANGUAGE, BUDDHISM, SHAMANISM AND CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com

Geography of Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region is located in the central-to-east northern part of China. It shares an international border with Mongolia (Outer Mongolia) and a relatively small part of Russia to the north. Officially Inner Mongolia is classified as a the provincial-level division of North China, but it stretches great distances to the east and west and has parts in Northeast China and Northwest China. Inner Mongolia borders eight provincial-level divisions: Heilongjiang and Jilin to the east; Liaoning to the southeast; Hebei, Shanxi and Shaanxi to the south and Ningxia and Gansu to the southwest — tying with Shaanxi for bordering the largest number of provincial-level divisions. The Yellow River cuts through northwestern Inner Mongolia. The largest cities in Inner Mongolia are Baotou (2.7 million in 2020), Hohhot (Huhhot) (2.9 million in 2012), Chifeng (1.2 million in 2020) and Ordos (2 million in 2014). The 2001 population figures were Baotou — 1,146,500; Hohhot — 817,500; Chifeng — 479,300; Wuhai — 343,800; and Tongliao — 324,300.

Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region is located in the central-to-east northern part of China. It shares an international border with Mongolia (Outer Mongolia) and a relatively small part of Russia to the north. Officially Inner Mongolia is classified as a the provincial-level division of North China, but it stretches great distances to the east and west and has parts in Northeast China and Northwest China. Inner Mongolia borders eight provincial-level divisions: Heilongjiang and Jilin to the east; Liaoning to the southeast; Hebei, Shanxi and Shaanxi to the south and Ningxia and Gansu to the southwest — tying with Shaanxi for bordering the largest number of provincial-level divisions. The Yellow River cuts through northwestern Inner Mongolia. The largest cities in Inner Mongolia are Baotou (2.7 million in 2020), Hohhot (Huhhot) (2.9 million in 2012), Chifeng (1.2 million in 2020) and Ordos (2 million in 2014). The 2001 population figures were Baotou — 1,146,500; Hohhot — 817,500; Chifeng — 479,300; Wuhai — 343,800; and Tongliao — 324,300.

Most of Inner Mongolia is a plateau averaging around 1,200 meters (3,940 feet) in altitude and covered by extensive loess and sand deposits. The Inner Mongolian plateau is the second largest plateau in China after the Tibetan plateau. The northern part consists of the Mesozoic era Khingan Mountains, and has more forests, made up mostly of Manchurian elm, ash, birch, Mongolian oak and a number of pine and spruce species. North of Hailar District, where some permafrost is present, forests are almost exclusively coniferous. In the south the natural vegetation is grassland in the east, with the landscape becoming increasingly arid and sparse as one move westward. Grazing is the dominant economic activity; desertification is problem..

A large part of Inner Mongolia is occupied by the northern side of the North China Craton, a tilted and sedimented Precambrian block. In the extreme southwest is the edge of the Tibetan Plateau where the autonomous region’s highest peak, 3,556-meter (11,670 foot) Main Peak in the Helan Mountains is located. Due to the large expanses of ancient, weathered rocks lying under a deep sedimentary cover, Inner Mongolia is a major mining district, with large reserves of coal, iron ore and rare earth minerals, which have spurred its industrial development.

Climate of Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia for the most part has a continental climate, with an annual precipitation of 50 to 450 millimeters. Great temperature extremes on an annual basis and a daily basis are characterized of the weather in Inner Mongolia. The climate is generally characterized by warm summers and very cold, long, dry winters with sharp temperature changes in spring and fall. In Alxa (Alshaa) county in southwestern the average temperatures can range from 37.7° C for July to below 0° C for January.

Due to its elongated shape, Inner Mongolia has a wide variety of regional climates. Throughout the region the climate is based off a four-season, monsoon climate. The winters in Inner Mongolia are very long, cold, and dry with frequent blizzards, though snowfall is generally minimal. The spring is short, mild, arid and windy, with large, dangerous dust storms and sandstorms. The summer is very warm to hot and relatively humid except in the west where it remains dry. Autumn is brief and sees a steady cooling, with temperatures below 0 °C (32 °F) reached in October in the north and November in the south.

Officially, most of Inner Mongolia is classified as either a cold arid or steppe. Small ares have been classified as humid continental in the northeast, and subarctic in the far north near Hulunbuir. Desertification is a major environmental problem in Inner Mongolia.

Marco Polo in Inner Mongolia

After a three-and-a-half year journey, Marco Polo (1254-1324), his father and uncle arrived in Shangdu (Xanadu), Kublai Khan's summer capital, not so far from Beijing, in what is now Inner Mongolia. It was1275 and Marco was 21. Word of the Polos journey had been relayed to Kublai Khan by Pony-Express-style messengers. Envoys of the Great Khan reached the Polos in central China. They escorted the Polos for the last 40 days of their trip to Shangdu.

Marco Polo met Kublai Khan soon after arriving in Shangdu. He called the great Khan a "Lord of Lords" and "the most powerful man in people and in lands and in treasure that ever was in the world" — and this was probably no exaggeration.

Marco Polo described great parties hosted by Kublai Khan with as many as 40,000 guests. He reported that the Khan once received "a gift of more than 100,000 whites horses very beautiful and fine" and employed 10,000 falconers, carrying gyrfalcons, peregrines, sake falcons and goshawks, and 20,000 dog handlers. He also had an unstated number of lions, leopards and lynxes to go after wild boars and other big animals and 5,000 elephants “all covered with beautiful clothes." He wrote that Kublai Khan's palace contained a dining area that could seat 6,000 and was surrounded by a four mile wall. These numbers are thought to be exaggerations.

History of Inner Mongolia

monk in Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, with its grasslands and deserts, runs across northern China, separating it from the independent country of Mongolia. For centuries, Chinese rulers have long cast a wary eye north, fearing the nomadic tribes that periodically swept south and toppled dynasties. Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “The Mongol nomads who have ranged across these blustery grasslands for millenniums have long had a tempestuous relationship with their Han Chinese neighbors to the south. Genghis Khan’s horseback conquerors overran Beijing in 1215, and Qing dynasty armies returned the favor four centuries later. By the time Mao’s Communist rebels declared victory in 1949, the Mongolians who occupied what became the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China had been by and large pacified through Han immigration, intermarriage and old-fashioned repression."

During the 1750s, when China was ruled by the Qing (Manchu) Dynasty (1644–1911) the first distinction was made between northern and southern Mongolia as a result of Manchu administrative policies,. The southern provinces — uiyuan, Chahar (or Qahar), and Jehol (or Rehol), known as Inner Mongolia — were virtually absorbed into China. The remainder of the region — the northern provinces, which became known as Outer Mongolia — was considered an "outside subordinate" by the Manchus, and it was largely ignored. After another 100 years, however, China again became alarmed by Russia's expansionist policy and colonial development in the regions north and west of Outer Mongolia. Increased Chinese activity in Outer Mongolia resulted in some economic and social improvements, but it also revealed to the Mongolians the possibilities of playing off the two great empires against each other. Chinese merchants and moneylenders had become ubiquitous, and the extent of Mongol debt had become enormous, by the early nineteenth century. The debt situation, combined with growing resentment over Chinese encroachment, gave impetus to Mongol nationalism by the beginning of the twentieth century. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In the 19th and 20th century, Mongolia became a pawn in a struggle between China and Russia. For most of its history Mongolia and nearby Siberia were vast wildernesses that no one cared much about. In the 19th century the Russian czars set up a "protectorate" in northern Mongolia, while the rest of Mongolia was controlled by the Chinese Qing Dynasty. As Chinese power waned Russian influence in Mongolia grew. The Russians were interested in Mongolia as transit area for a railroad from Siberia across Manchuria to Vladivostok and the Russian concessions in China. The Russian came to control what became Outer Mongolia and the Chinese controlled Inner Mongolia. Russia supported Outer Mongolian declarations of independence in the period immediately after the Chinese Revolution of 1911. Russian interest in the area did not diminish, even after the Russian Revolution of 1917, and the Russian civil war spilled over into Mongolia in the period 1919 to 1921. Chinese efforts to take advantage of internal Russian disorders by trying to reestablish their claims over Outer Mongolia were thwarted in part by China's instability and in part by the vigor of the Russian reaction once the Bolshevik Revolution had succeeded.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937 – 1945) much of Inner Mongolia was occupied by the Japanese. After World War II China regained the parts of Inner Mongolia it lost to Japan; Soviet-Mongolian military units moved into Inner Mongolia and Manchuria; and Stalin and Chiang Kai-shek signed an agreement that recognized Mongolia as an independent country. After Chiang Kai-shek fled to Taiwan, Chiang’s Chinese nationalists denounced the agreement. Maps in Taiwan today show Outer Mongolia as a province of China. During the Communist revolution the Communists had more important things to worry about than the reunification of Mongolia. The Communist Chinese recognized Mongolia in 1946 (formally in 1950) and Mongolia was admitted to the U.N. despite opposition by the U.S. and Taiwan.

See Separate Articles: MONGOLS AFTER THE END OF THE MONGOL EMPIRE factsanddetails.com RUSSIANS VERSUS CHINESE IN MONGOLIA factsanddetails.com MONGOLIA RISES TO NATIONHOOD DURING THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTIONARY PERIOD factsanddetails.com MONGOLIA AS A COMMUNIST STATE factsanddetails.com MONGOLIA IN THE WORLD WAR II ERA factsanddetails.com

History of Inner Mongolia After the Communist Takeover

Members of China's Han majority trickled into Inner Mongolia, often fleeing famine and poverty. But the flow increased after the founding of the communist state in 1949, and has turned into a flood in recent years on the back of boom in mining, especially of coal.

When the Republic of China was established in 1949, the Soviets had firm control over Outer Mongolia and Communist China was not ready to fight the Soviet Union for it. It was not until after the Soviets rejected political unification that the majority of Inner Mongolian leaders agreed to back the Chinese Communist party.

Under the Communists, Chinese overan Inner Mongolia, making Mongolians a minority there. The process of diluting the power of local people with massive migrations of Han Chinese was successfully carried out in Inner Mongolia as it developed and industrialized. Beginning in the 1950s, Inner Mongolia was developed for agriculture. Millions of acres of steppe and desert was plowed under for farm land and water was taken from the Yellow River for irrigation. Many Chinese settlers moved in and it wasn't long before they outnumbered Mongolians. Towns on the Yellow River were turned into industrial centers with plants to process agricultural and livestock products.

People's Congress in Inner Mongolia

Parts of Northeast China were added to Inner Mongolia and area traditionally part of Inner Mongolia were added to ther provinces. Gansu province, for example, contains areas that have traditionally been part of Inner Mongolia. The Autonomous Region of Inner Mongolia was established in 1947 on the area of former Republic of China provinces of Suiyuan, Chahar, Rehe, Liaobei and Xing'an along with the northern parts of Gansu and Ningxia.

Unlike Tibet and Xinjiang, which have exploded in violent anti-government protests in recent years, Inner Mongolia has been generally quiet. That's partly due to the perception among Mongols that they have been better off under Chinese rule than their ethnic brethren in impoverished Mongolia, said Barry Sautman of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. The per capita annual per capita GDP of Inner Mongolia exceeded $7,000 in 2010, more than triple that of Mongolia

Mongols Dominated by Han Chinese in Inner Mongolia

Mongols now make up about 17 percent of Inner Mongolia's population of 25 million people. At one time they presumably made up near 100 percent. Even as an exemption from the nation's one-child policy granted to minorities helped expand their numbers, Mongolians are still outnumbered by Han almost five to one. Inner Mongolia has traditionally been southern half of the homeland of the Mongols. A large number of Mongolians live in the central region of Xinjiang. Inner Mongolia is supposed to have a high degree of autonomy, as are Tibet and Xinjiang in the far west. But Beijing keeps a tight rein on the region, fearing ethnic unrest in strategic border and resource areas.

On Mongol assimilation, Kerry Brown wrote in his book Struggling Giant: China in the 21st Century, “Dressing up in colorful clothes, dancing exaggerated dances, eating mutton and drinking white spirit are all O.K. But musing about just what the historical claims of the current Chinese state on Inner Mongolia are, or writing more trenchant articles in Chinese about the gradual annexation of the region are good ways to be rewarded with unwanted police attention and very probably lengthy prison sentences."

Relations between the Mongols and Han Chinese in Inner Mongolia varies from amiable to mild antagonism to overt hostility. Even so most Mongols regard themselves as citizens of China and do not have a strong desire to reunify with Mongolia. They arguably are not as independence-minded and anti-Beijing — at least on the surface — than Tibetans and Uighurs in Xinjiang. Mongols tend to have issue with the Chinese government more for not providing enough benefits. There are probably feelings of powerlessness and acceptance that there is little they can do to change the situation. Some Han Chinese in Inner Mongolia believe the government's affirmative action policy favors the Mongols too much.

Mongolians own or earn only a fraction of wealth generated in Inner Mongolia. Ethnic tensions exist and occasionally explode. Protests erupted across the region in May 2011, when Han drivers killed two Mongolian herders as they tried to block a caravan of coal trucks. Inner Mongolian authorities deployed riot police and barricaded university campuses. The drivers were hauled before a judge; they confessed, and one was promptly executed. The protests ended as quickly as they began.

Language and Culture of Inner Mongolia

The official languages are Chinese and Mongolian, the latter written in the Mongolian script, as opposed to the Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet used in the state of Mongolia. The Han Chinese of Inner Mongolia come from all over China and speak a variety of dialects, depending on the region they originated from. The Han Chinese In the the eastern parts of Inner Mongolia tend to speak Northeastern Mandarin, which belongs to the Mandarin group of dialects; those in the central parts, such as the Huang He valley, speak varieties of Jin, another subdivision of Chinese, due to its proximity to other Jin-speaking areas in China such as the Shanxi province. Cities such as Hohhot and Baotou both have their unique brand of Jin Chinese such as the Zhangjiakou–Hohhot dialect which are sometimes incomprehensible with dialects spoken in northeastern regions such as Hailar.

Alxa area of Inner Mongolia

Mongols in Inner Mongolia speak Mongolian dialects such as Chakhar, Xilingol, Baarin, Khorchin and Kharchin Mongolian and, depending on definition and analysis, further dialects or closely related independent Central Mongolic languages such as Ordos, Khamnigan, Barghu Buryat and the arguably Oirat dialect Alasha. The standard pronunciation of Mongolian in China is based on the Chakhar dialect of the Plain Blue Banner, located in central Inner Mongolia, while the grammar is based on all Southern Mongolian dialects. This is different from the Mongolian state, where the standard pronunciation is based on the closely related Khalkha dialect. There are a number of independent languages spoken in Hulunbuir such as the somewhat more distant Mongolic language Dagur and the Tungusic language Evenki. Officially, even the Evenki dialect Oroqin is considered a language.

By law, all street signs, commercial outlets, and government documents must be bilingual, written in Mongolian and Chinese. There are three Mongolian TV channels in the Inner Mongolia Satellite TV network. In public transportation, all announcements are to be bilingual. Many ethnic Mongols, especially the young, speak fluent Chinese. Mongolian is receding in urban areas. But rural ethnic Mongols have kept more of their traditions. In terms of written language, Inner Mongolia has retained the classic Mongol written script as opposed to Outer Mongolia's adoption of Cyrillic.

The vast grasslands have long symbolised Inner Mongolia. Mongolian art often depicts the grassland in an uplifting fashion and emphasizes Mongolian nomadic traditions. The Mongols of Inner Mongolia still practice their traditional arts. The famous actress Siqin Gaowa is an ethnic Mongol from Inner Mongolia. A popular career in Inner Mongolia is circus acrobatics. The famous Inner Mongolia Acrobatic Troupe travels and performs with the renowned Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus. Among the Han Chinese of Inner Mongolia, Jinju or Shanxi Opera is a popular traditional form of entertainment.

Inner Mongolian cuisine has Mongol roots and consists of dairy-related products and hand-held lamb . In recent years, franchises based on Hot pot have appeared Inner Mongolia, the most famous of which is Xiaofeiyang . Famous Inner Mongolian commercial brand names include Mengniu and Yili, both of which began as dairy product and ice cream producers.

Mongolian hot pot is a traditional winter dish consisting of frozen bean curd, bean flour noodles, beef and mutton cooked with other ingredients and spices in a hot pot in boiling oil and broth. In hot pot restaurants, customers often cook the ingredients in their own individual pots or a pot eaten collectively by a group that is heated by a burner under the table. When the ingredients are ready you pluck them out of the pot with your chopsticks and dip them in a tasty sauce and eat them. Hot pot was created by nomads on the steppes of Mongolia. A Mongolian barbecue — an American invention — consists of meat, poultry and vegetables picked by the customer and then cooked on a big grill.

Economy of Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia has been home to one of China’s most rapidly developing economies. Its GDP grew an average of 17 percent annually between 2001 and 2011, faster than any Chinese province. Inner Mongolia specializes in animal husbandry, product processing, metallurgy, forestry, chemical and building materials, and tanning industries. The region's textile industry is a major producer of cotton, wool, and cashmere goods. Specialities of the region known far and wide include mushrooms and day lily flowers. Other products include wheat, millet, kaoling, soybeans, sugar beets, iron, coal, salt, soda, sugar and animal products.

William Jankowiak, Ian Skoggard, and John Beierle wrote: The integration of Inner Mongolia into the global economy has provided economic incentives for herders to no longer concentrate on raising a variety of animals such as horses, cattle, camels, sheep, and goats. Instead there is a preference for sheep and goats, which have a higher market value. The rapid economic differentiation among herders has meant that some are subject to market vagaries and depend largely on subsistence production; while others herders who live near towns are economically advantaged as numerous traders want to buy raw materials from them. Still, from the late 1980's till 2005, the prices of animal products have failed to keep up with inflation and the buying power of the average pastoralist has been reduced. Tourism is another major source of income in Inner Mongolia. Baotou is the region's largest consumer center, followed by Hohhot, and Chifeng. [Source: William Jankowiak, Ian Skoggard, and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Inner Mongolia dominates the world's cashmere industry. There are millions of cashmere goats grazing the region’s grasslands and the infrastructure to process the wool not only for Inner Mongolia but also for Mongolia and the rest of China as well. China began its drive to become a cashmere superpower in the 1990s. Production increased from around 9,000 tons in 1990 to 12,000 tons in 1998. Finishing facilities are capable of producing 20 million cashmere pieces a year. The largest company is called Eerduosi. It produces about a third of the world’s cashmere and controls half the output of China It employs 13,000 people and is 44 percent owned by the Chinese government. In recent years it has decided that cashmere is not enough, It plans to invest almost $100 million to diversify into banking, electricity and property.

Mining and Natural Resources in Inner Mongolia

There is a lot of mining in Inner Mongolia. Many rare earths, minerals vital for many industries, are mined and produced in Inner Mongolia. Other natural resources include copper and especially coal. State-owned mining companies arrived en masse, and changed the region indelibly — quickly. Towns near mining areas such as Xi Wuqi grew from a cluster of one-storey red-brick homes into a city of 70,000 filled with Han-owned stores in a few years.

More than 60 mineral resources such as coal, iron, chromium, manganese, copper, lead, zinc, gold, silver, tin, mica, graphite, rock crystal and asbestos have been found. It is the world’s largest source of rare earths. The region is rich in coal, cement limestone, and siliceous clay. Inner Mongolia has China's largest iron ore mine at Baiyunerbo, which is also the largest rare earth mine in China. The reserves of rare earth minerals in the region account for 90 percent of the nation's total. With an extensive coal deposits, as well as, the iron ore, Inner Mongolia has become an important steel production center. Baotou Iron and Steel Company is one China's major steel producers. The region's reserves of niobium and natural soda also rank it first in the country.

Inner Mongolia is China's largest producer of coal, a commodity that feeds well over half the country's power plants and on which China depends for its breakneck economic growth. Coal production soared threefold between 2005 and 2010, reaching 782 million tons in 2010 according to government statistics. Inner Mongolia's boom in the mining of coal and rare earths in recent decadeshas drawn more workers into the region, further degraded the grasslands where herders grazed their sheep and cattle. See Coal, Rare Earths

Environment and Environmental Problems in Inner Mongolia

The Greater Hinggan Mountain Range in the east part of the region boasts China's largest forests, which are also a fine habitat for a good many rare species of wildlife. This unique natural environment makes the region a famous producer of precious hides, pilose antler, bear gallbladder, musk, Chinese caterpillar fungus (Cordyceps sinensis), as well as 400 varieties of Chinese medicinal herbs, including licorice root, "dangshen" (Codonopsis pilosula), Chinese ephedra (Ephedra sinica), and the root of membranous milk vetch (Astragalus membranaceus).

Inner Mongolia shares the vast Gobi desert and an immense area of dusty grassland with the country of Outer Mongolia to the north. Traditionally inhabited by nomadic Mongolian tribesmen who lived in gers (circular tents also known as yurts), Inner Mongolia is a desolate place with burning hot summers, frigid winters and huge, springtime sand storms that send gravel flying and sandblast cars. The grasslands were home to wild camels and herd of horses, but these are largely gone. According to one old saying, Inner Mongolia is so barren, that if you want to hang yourself you have to walk a 100 miles to find a tree. Desertification caused by overgrazing, cultivation of the region's marginal agricultural land and erosion of soil by wind and rain has made some parts of the province more desolate than it would otherwise be.

Mining and overgrazing has left lasting environmental — and social — damage in Inner Mongolia. Strip mining has devastated large swaths of pasture land, forcing traditional nomadic herders them to move into newly built cities with few economic prospects. A process of diluting the power of local people with massive migrations of Han Chinese was successfully carried out in Inner Mongolia as it developed and industrialized. Beginning in the 1950s, Inner Mongolia was developed for agriculture. Millions of acres of steppe and desert was plowed under for farm land and water was taken from the Yellow River for irrigation. Many Chinese settlers moved in and it wasn’t long before they outnumbered Mongolians. Towns on the Yellow River were turned into industrial centers with plants to process agricultural and livestock products.

Desertification has been a severe problem for some time. According to one old saying, Inner Mongolia is so barren, that if you want to hang yourself you have to walk a 100 miles to find a tree. Desertification caused by overgrazing, cultivation of the region's marginal agricultural land and erosion of soil by wind and rain has made some parts of the region more desolate than it would otherwise be. The region is famous for the yellow sand that is picked up by spring winds and deposited on Beijing and other places to the East.

Reforestation and anti-desertification projects launched after 1949 have had some success. To keep the desert from encroaching on vegetated land, sand dunes have been planted with lattice-like configurations of shrubs to keep them in one place. And, in what has been described as the world's most ambitious reforestation project, land-stabilizing shrubs and trees have been planted in rows across the entire southern part of the province. Stretching from Xinjiang to Heolongjang, this "Great Green Wall" covers a strip of land 4,000 miles in length and protects farmland in northern China from desertification and scouring winds.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2021