HOHHOT

Hohhot (500 kilometers west of Beijing) is the capital of Inner Mongolia. It looks like a typical Chinese city with wide roads, cycle lanes and squares. In old city you can find ancient mosques, white-bearded Muslims and markets filled with sheep heads and carcasses.

Hohhot is the capital if Inner Mongolia and home to about 2 million people in the cityof which about 87 percent are Han Chinese and 10 percent are Mongol. The city can be reached in less than three hours on the fast trains or 12 hours by regular train. The Hohhot Metro began operation in 2019 and consists of Line 1 which runs from Yili Health Valley (Tumed Left Banner) to Bayan (Airport) in Saihan District and has 21.7 kilometers of track and 20 stations. Line 2 is slated to open in 2020.

On the city in the 1980s, the travel writer Paul Theroux wrote: it was "not really a city — it was a garrison that had been plunked down in the Mongolian prairie, and every building in it looked like a factory. It had been planned and much of it built by the Russians, but even its newer structures looked horrible." The main landmark is a "Chinese-style" mosque with a curved-tile roofs, red painted eaves and painted clock face permanently showing the time of 12:45.

Sights in Hohhot: 1) Dazhao Temple, a Lamaist temple built in 1580, is known for three things: a statue of Buddha made from silver, elaborate carvings of dragons, and murals. 2) Xiaozhao Temple, also known as Chongfu temple, is a Lamaist temple built in 1697 and favoured by the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). 3) Xilituzhao Temple is the largest Lamaist temple in the Höhhot area, and once the center of power of Lamaism in the region. 4) Five-pagoda Temple is located in the capital of Inner Mongolia Hohhot. It is also called Jingangzuo Dagoba, used to be one building of the Cideng Temple.

Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Maps of Hohhot: chinamaps.org ;China Highlights China Highlights ;

Budget Accommodation: Check Lonely Planet books; Getting There: Hohhot is accessible by air and bus and lies on the main east-west train line between Beijing and Urumqi. Travel China Guide (click transportation) Travel China Guide Hohhot Subway Map: Urban Rail urbanrail.net

See Separate Articles: INNER MONGOLIA: ITS HISTORY, STEPPES, ETHNIC GROUPS AND NEOLITHIC CULTURES factsanddetails.com ; GOBI DESERT SIGHTS IN INNER MONGOLIA AND GANSU IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Tomb of Zhaojun

Tomb of Zhaojun (seven kilometers south of Hohhot) is the tomb of Wang Zhaojun, a Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) palace lady-in-waiting who became the consort of a Xiongnu ruler. She is one of the Four Beauties of China. Even though she was a concubine of a Chinese emperor she went Mongolian to marry the horseman chieftain to make peace between the Han Chinese and the Xiongnu.

Wang Zhaojun, also known as Wang Qiang, was born in Baoping Village, Zigui County (in current Hubei Province) in 52 B.C. in the the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC–8 AD). She was a gorgeous lady and great at painting, Chinese calligraphy, playing chess and Zheng (a kind of musical instrument in ancient China). In 36 B.C., Wang Zhaojun was selected as royal maid to serve the royal members. At that time, the Han Empire was having conflicts with Xiongnu, a nomadic people from Central Asia based in present-day Mongolia. Before her life took a dramatic turn, she was a neglected palace lady-in-waiting, never visited by the emperor.

In 33 B.C., Hu Hanye, leader of the Xiongnu paid a respectful visit to the Han emperor, asking permission to marry a Han princess, as proof of the Xiongnu people's sincerity to live in peace with the Han people. Instead of giving him a princess, which was the custom, the emperor offered him five women from his harem, including Wang Zhaojun. No princess or maids wanted to marry a Xiongnu leader and live a distant place so Wang Zhaojun stood out when she agreed to go to Xiongnu.

The historical classic, "Hou Han Shu", reveals that Wang Zhaojun volunteered to marry Hu Hanye. When the Han emperor finally met her, he was astonished by her beauty, but it was too late for regrets. She married Hu Hangye and had children by him. Her life became the foundation and unfailing story of "Zhaojun Chu Sai", or "Zhaojun Departs for the Frontier". Peace ensued for over 60 years thanks to her marriage. [Source: Peng Ran, CRIENGLISH.com, July 17, 2007]

In the most prevalent version of the "Four Beauties" legend, it is said that Wang Zhaojun left her hometown on horseback on a bright autumn morning and began a journey northward. Along the way, the horse neighed, making Zhaojun extremely sad and unable to control her emotions. As she sat on the saddle, she began to play sorrowful melodies on a stringed instrument. A flock of geese flying southward heard the music, saw the beautiful young woman riding the horse, immediately forgot to flap their wings, and fell to the ground. From then on, Zhaojun acquired the nickname "fells geese" or "drops birds." [Source: Wikipedia +]

Statistics show that there are about 700 poems and songs and 40 kinds of stories and folktales about Wang Zhaojun from more than 500 famous writers, both ancient (Shi Chong, Li Bai, Du Fu, Bai Juyi, Li Shangyin, Zhang Zhongsu, Cai Yong, Wang Anshi, Yelü Chucai) and modern (Guo Moruo, Cao Yu, Tian Han, Jian Bozan, Fei Xiaotong, Lao She, Chen Zhisui). +

See Separate Article FOUR BEAUTIES OF ANCIENT CHINA: XI SHI, WANG ZHAOJUN, DIAOCHAN, YANG GUIFEI factsanddetails.com

Steppes Near Hohhot

Xilamuren Steppe (80 kilometers north of Hohhot) located on a 5000-foot-high grassy plateau and is one of the first steppe areas to be set up for tourists, who stay in "yurt-hotels" and enjoy activities such as horse and camel riding and visiting nomad homes. Tourists are also often entertained with traditional Mongolian wrestling matches and camel races and taste Mongolian cuisine which features mutton prepared in a number of ways. At some yurt hotels the yurts are organized around a small central dining hall with a set or portable disco lights, a karaoke machine and sound system.

Gegendala Steppe (160 kilometers north of Hohhot) is another tourist steppe. The yurt-hotels here are cement buildings shaped like yurts. In additions to activities listed above, tourists can ride in donkey and camel carts and participate in a Mongolian version of a wagon train. They also can learn Mongolian archery and attend a nomad bonfire party.

Xanadu: UNESCO World Heritage Site and Home of Kublai Khan’s Pleasure Palace

Kublai Khan

Xanadu (320 kilometers northwest of Beijing, 150 kilometers east-northeast of Hohhot) was the home of Kublai Khan's summer pleasure palace, immortalized in a poem by Samuel Cooleridge Taylor. All that remains of it are a few acres of mud walls as high as four meters and a few marble blocks. The Mongol name for Xanadu means "City of 108." Xanadu (Shangdu) was established by Kublai Khan before he established Daidu (Beijing). Xanadu was destroyed in 1368 and would likely have been forgotten were in not for Marco Polo's accounts of the palace and Samuel Tayler Coleridge's poem Kublai Khan.

Site of Xanadu was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2012. According to UNESCO: “North of the Great Wall, the Site of Xanadu encompasses the remains of Kublai Khan’s legendary capital city, designed by the Mongol ruler’s Chinese advisor Liu Bingzhdong in 1256. Over a surface area of 25,000 hectares, the site was a unique attempt to assimilate the nomadic Mongolian and Han Chinese cultures. From this base, Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368) that ruled China over a century, extending its boundaries across Asia. The religious debate that took place here resulted in the dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism over northeast Asia, a cultural and religious tradition still practised in many areas today. The site was planned according to traditional Chinese feng shui in relation to the nearby mountains and river. It features the remains of the city, including temples, palaces, tombs, nomadic encampments and the Tiefan’gang Canal, along with other waterworks. [Source: UNESCO]

“From Xanadu, the mounted warriors of Kublai Khan unified the agrarian civilisations of China, and partly assimilated to the latter’s culture, while extending the Yuan empire right across North Asia. The plan of Xanadu, with Palace and Imperial cities enclosed partly by the Outer City containing evidence of the nomadic encampments and royal hunting enclosure, comprises a unique example of this cultural fusion. Evidence of large water control works instigated to protect the city exists in the form of remains of the Tiefan’gan Canal. As the place where Kublai Khan rose to power, hosted religious debates and entertained foreign travellers whose writings gave inspiration down the centuries, it has achieved legendary status in the rest of the world and is the place from where Tibetan Buddhism expanded.

Xanadu Archaeological Site

According to UNESCO: “The Site of Xanadu is the site of a grassland capital characteristic of cultural fusion, witnessing clashes and mutual assimilation between the nomadic and agrarian civilisations in northern Asia. Located on the southeast edge of the Mongolian plateau, it was the first capital (1263-1273) of Kublai Khan and later the summer capital (1274-1364) of the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368). The city site and associated tombs are located on the grassland steppe with a north south axis determined by traditional Chinese feng shui principles, backed by mountains to the north and a river to the south. [Source: UNESCO]

“The Site of Xanadu was abandoned in 1430. The large archaeological site now generally covered by grassland preserves the overall urban plan and city site of Xanadu as built and used in the 13th and 14th centuries. Wall lines of the Palace City, Imperial City and Outer City which together display the traditional urban planning of central China and arrangements for Mongolian tribal meetings and hunting can be clearly perceived, as can mounds indicating palace and temple buildings, some of which have been excavated, recorded and reburied. The remains of the neighbourhoods outside the gates, Tiefan’gan canal and the tomb areas, all within their natural and cultural environment. The latter preserves the natural elements crucial for the siting of the city — mountains to the north and water to the south, together with the four existing types of grassland landscape, especially the Xar Tala Globeflower plain associated with the river wetlands. The Site of Xanadu can be clearly read in the landscape.

“Archaeological excavation and historical records bear witness to the authenticity of the property as representing the interchange between Mongolian and Han people in terms of capital design, historical layout and building materials. The Tombs authenticate the historical claims concerning the life of both Mongolian and Han people in Xanadu. Apart from repairs to the Mingde Gate and the east wall of the Imperial City, there has been minimal intervention in the structure. The geographical environment and grassland landscape are intact and still convey the environmental setting and spatial feeling of the grassland capital.”

The site is important because: 1) “The location and environment of the Site of Xanadu exhibits influence from both Mongolian and Han Chinese values and lifestyles. The city site exhibits an urban planning pattern indicative of integration of the two ethnicities. From the combination of Mongolian and Han ideas and institutions the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368) was able to extend its control over an extremely large part of the known world at that time. The Site of Xanadu is a unique example of an integrated city plan involving different ethnic communities. 2) The Site of Xanadu is exceptional testimony to the supreme rule of the Yuan conqueror Kublai Khan, the assimilation and conversion to the culture and political system of the conquered, and the determination and effort of the conqueror in adhering to and maintaining the original cultural traditions. 3) The site location and environment of the Site of Xanadu together with its urban pattern demonstrates a coexistence and fusion of nomadic and farming cultures. The combination of a Han city plan with the gardens and landscape necessary to the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368)’s Mongolian lifestyle at Xanadu resulted in an outstanding example of urban layout that illustrates a significant stage in human history. 4) The city of Xanadu hosted the great debate between Buddhism and Taoism in the 13th century, an event that resulted in dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism over Northeast Asia.

Marco Polo Arrives at Xanadu

After a three-and-a-half year journey from Venice, Marco Polo (1254-1324), his father and uncle arrived in Shangdu (Xanadu), Kublai Khan's summer capital, not so far from Beijing, in 1275, when Marco was 21. Word of the Polos journey had been relayed to Kublai Khan by Pony-Express-style messengers. Envoys of the Great Khan reached the Polos in central China. They escorted the Polos for the last 40 days of their trip to Shangdu. [Sources: Mike Edwards, National Geographic, May 2001, June 2001, July 2001]

According to the Silk Road Foundation: “ Finally the long journey was nearly over and the Great Khan had been told of their approach. He sent out a royal escort to bring the travellers to his presense. In May 1275 the Polos arrived to the original capital of Kublai Khan at Shang-tu (then the summer residence), subsequently his winter palace at his capital, Cambaluc (Beijing). By then it had been 3 and half years since they left Venice and they had traveled total of 5600 miles on the journey. [Source: Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com/artl/marcopolo]

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Marco Polo arrived in the East with his father and uncle at a crucial turning point in history: The 300-year-old Song Dynasty was on the verge of collapse and Kublai was about to become the first non-Chinese emperor of China. But even as the khan was trying to take China, his own people were turning on him in a civil war, upset over what they saw as his increasing softness and excessive Sinification."Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, September 19, 2014 ^|^]

Marco Polo Meets Kublai Khan at Xanadu

Marco Polo met Kublai Khan soon after arriving in Shangdu. He called the great Khan a "Lord of Lords" and "the most powerful man in people and in lands and in treasure that ever was in the world" – -and this was probably no exaggeration. [Sources: Mike Edwards, National Geographic, May 2001, June 2001, July 2001]

Marco recalled it in detail on the greatest moment when he first met the Great Khan:" They knelt before him and made obeisance with the utmost humility. The Great Khan bade them rise and received them honorably and entertained them with good cheer. He asked many questions about their condition and how they fared after their departure. The brothers assured him that they had indeed fared well, since they found him well and flourishing. [Source: Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com/artl/marcopolo]

“Then they presented the privileges and letters which the Pope had sent, with which he was greatly pleased, and handed over the holy oil, which he received with joy and prized very hightly. When the Great Khan saw Marco, who was then a young stripling, he asked who he was. 'Sir' said Messer Niccolo, 'he is my son and your liege man.' 'He is heartly welcome,' said the Khan. What need to make a long story of it? Great indeed were the mirth and merry-making with which the Great khan and all his Court welcomed the arrival of these emissaries. And they were well served and attended to in all their needs. They stayed at Court and had a place of honor above the other barons."

Marco Polo and Samuel Taylor Coleridge on Xanadu

Marco Polo estimated the length of Shangdu's pleasure palace walls to be 16 miles around (Chinese archaeologists have estimated that the true figure is 5.5 miles) and described monasteries of Buddhist "idolaters" who supplied Kublai Khan's court with sorcerers and astrologers.

On Kublai Khan's pleasure palace at Xanadu, Marco Polo wrote: "There is at this place a very fine marble palace, the rooms of which are all gilt and painted with figures of men and beasts and birds, and with a variety of trees and flowers, all executed with such exquisite art that you regard them with delight and astonishment...Round this palace is a wall...and inside the Park there are fountains and rivers and brooks, and beautiful meadows, with all kinds of wild animals (excluding such as are of a ferocious nature), which the Emperor has procured and placed there to supply food for his gyrfalcons and hawks...The gyrfalcons alone amount to more than 200.

"At a spot in the park where there is a charming wood he has another Palace built of cane. It is gilt all over, most elaborately finished inside and decorated with beasts and birds of very skillful workmanship. It is reared on gilt and varnished pillars, on each of which stands a dragon entwining the pillar with tail and supporting the roof on outstretched limbs. The roof is also made of canes, so varnished that it is quite waterproof."

“Once a week he comes in person to inspect [falcons and animals] in the mew. Often, too, he enters the park with a leopard on the crupper of his horse; when he feels inclined, he lets it go and thus catches a hare or stag or roebuck to give to the gyrfalcons that he keeps in the mew. And this he does for recreation and sport. The lord abides at this Park of his, dwelling sometimes in the Marble Palace and sometimes in the Cane Palace for three months, to wit, June, July and August, preferring this residence because it is by no means hot; in fact it is a very hot place. When the 28th day of August arrives, he takes his departure, and the Cane Palace is taken to pieces...the Great Khan had it so designed that it can be moved whenever he fancies... It is held in place by more than 200 chains of silk.

The British poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) wrote a weird, largely nonsensical poem about Kublai Khan and Xanadu called is Kubla Khan; or a Vision in a Dream, which he conceived after falling asleep while reading and taking opium. Colerdige later wrote, "During three hours of profound sleep, he composes 300 lines of poetry. After he woke up he wrote down the 54 lines of Kubla Khan when he was interrupted by a visitor. When he returned to his desk he could no longer remember his dream poem."

Kubla Khan; or a Vision in a Dream begins:

In Xanadu die Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure'dome decree

Where Alph, the sacred river ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea

And ends with:

And all should cry Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread,

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise

Baotou

Baotou (150 kilometers west of Hohhot) contains one of the largest steel mills in China and is major center of rare earth production. At one time, 170,000 of the city's people work in steel production. In the 1950s a 900,000-pound blast furnace was built to make it a major steel producing center utilizing local iron and coal.

By some measures Baotou is the largest city in Inner Mongolia. It is home to 2.5 million people, and according to a 2009 Lonely Planet guidebook “sprawls across more than 20 kilometers of dusty landscape, much of it industrialised and polluted. Unless you have a particular interest in steel production, there is little reason to stop.” Touristy sites in area include grasslands and desert, and the mausoleum for Genghis Khan, which don’t contain his remains. Lonely Planet says that city of Dongsheng was a better option for an overnight than “hideous Baotou” and the thing really worth seeing was a Tibetan monastery. A YouTube video posted by an English teacher in the city says that Baotou is “run by gangsters” and is so dangerous that most men carry knives. The Daily Mail ran an article about a secret lake of toxic chemicals patrolled by security guards.

Web Sites: Travel China Guide (click Baotou) Travel China Guide Budget Accommodation: Check Lonely Planet books; Getting There: Baotou is accessible by air and bus and lies on the main east-west train line between Beijing and Urumqi. Travel China Guide (click Baotou and then transportation) Travel China Guide

Baotou, "Middle East" of Rare Earths

Inner Mongolia Baotou Steel Rare-Earth Hi-Tech Co. is China's biggest rare earth producer. The rare earth reserves at the Bayan Obi mine in Inner Mongolia are thought to be the largest in any single location in the world.

“Baotou, a city of 1.8 million people in Inner Mongolia (an autonomous region of China), is regarded as the world's “capital of rare earths." Located about 650 kilometers (404 miles) west of Beijing, Baotou's mines hold about 80 percent of China's rare earths, Chen Zhanheng, director of the academic department of the Chinese Society of Rare Earths in Beijing told National Geographic. But Baotou has paid a steep price for its supremacy. Some of the most environmentally benign and high-tech products turn out to have very dirty origins indeed. [Source: Tim Folger, National Geographic, June 2011 ]

Chris Buckley of Reuters wrote, “Baotou wants to remake itself as a crucible of China's ambitions to turn its rare earths into green-tinged gold. The city has a rare earths high-tech zone, a shiny Rare Earths Tower for officials and investors, and Rare Earths Street. The city's Rare Earths Park features carvings of scientists and leaders who pushed China to turn its reserves into an engine for economic growth, including Deng Xiaoping, the revolutionary veteran who guided the nation to market economic reforms. "The Middle East has oil, and China has rare earths," a carving records Deng as saying." [Source: Chris Buckley, Reuters, November 4, 2010]

“The Baotou Steel Rare-Earth Group is at the heart of China's ambitions to turn rare earths into a lucrative ingredient of growth. It dominates rare earths production in Inner Mongolia, where most of the ores come out of the ground mixed with iron ore, which is the parent company Baotou Steel's main business. China wants enough rare earths for its expansion into clean technology, especially advanced wind turbines, hybrid and electric vehicles and other innovations. Minutes from the mines of Bayan Obo north of Baotou city, hundreds of wind turbines just above the grasslands, their three blades and parts using rare earths in compounds that give them strength and lightness."

Mining and Production of Rare Earths in Baotou

The mining of rare earths is difficult, time-consuming and expensive and produces highly toxic by-products. The elements are usually found scattered in small fragments among rocks and must be separated and then processed. The procedure is rarely eco-friendly, creating hundreds of gallons of salty wastewater per minute, consuming huge amounts of electricity, requiring toxic materials for the refining process and occasionally unearthing dirt that is radioactive.

Production costs in China for rare earth are about $5.59 per kilogram. High mining costs and damaging techniques pushed most rare earth mines outside of China out of business in the early 1990s. Only China kept its mines going, positioning itself for the ensuing high-tech boom and the resulting rare earth-hungry products. [Source: Tiffany Hsu, Los Angeles Times, February 20, 2011]

Rare earth production and processing is dirty and primitive. Separating out the minerals is usually done by dousing the rare earths in acids and other chemicals. Separating rare earths is not easy to do because they're chemically so similar. Reporting from the Huamei plant in Baotou, Chris Buckley of Reuters wrote, “China's quest for a green future built on rare earths metals seems a world away from Ren Limin as he casts lumps of one of the metals in a chemical-spattered shed thick with acrid fumes. Ren tends cauldrons of sputtering acid, additives and ore in a shed in north China's Inner Mongolia region, smelting lanthanum, one of the 17 rare earths that Beijing hopes will power the nation up the clean technology ladder." [Source: Chris Buckley, Reuters, November 4, 2010]

“Yet Ren and a workmate use few safety protections as they stir and poke the red-hot cauldrons. Holes in the roof and windows act as main ventilation. "This place doesn't have anything but it's got mines. We live off the rare earth mines," Ren, who gave his age as 32 but looked years older, told Reuters journalists who visited Baotou. "It's not that dangerous. You get used to the smells, but there's also the heat," he said. "We sell it on. That's all I know. I'm not sure who buys it or what it's for," he said of a pile of lanthanum bricks lying on the floor, among discarded cotton gloves and scrap." [Ibid]

“Ren worked without a mask but wrapped a towel around his face and donned a visor when pouring the molten compound into molds. He said they made 1,100 yuan ($165) a metric ton, working 12-hour days, with a few days off every two weeks. The plant he works in lies in a northern corner of Baotou, a city and surrounding expanse of Inner Mongolia that produces more than half of the world's rare earths, especially the lighter ones, from the fenced-off Bayan Obo mines. [Ibid]

“The government says it wants to end unfettered exploitation of rare earths, and has been shutting unlicensed mines and smelters. But China's biggest producers still pollute at levels far beyond what would be allowed in the United States, Australia and other countries now looking to ramp up production as Beijing curbs exports.

Pollution from the Production of Rare Earths

Tim Folger wrote in National Geographic, “Villagers near Baotou reportedly have been relocated because their water and crops have been contaminated with mining wastes. Every year the mines near Baotou produce about ten million tons of wastewater, much of it either highly acidic or radioactive, and nearly all of it untreated. [Source: Tim Folger, National Geographic, June 2011 ]

Near Baotou city, where Baotou Steel Rare-Earth Group processes the metals on a vast scale, villagers said the resulting toxins were poisoning them, their water and air, crops and children. At least one official has backed that claim. "If we take into account the resource and environmental costs, the progress of the rare earths industry has come at a massive price to society," Su Wenqing, a Baotou rare earths industry official wrote in a study published last year. [Source: Chris Buckley, Reuters, November 4, 2010]

Chris Buckley of Reuters wrote, “At the heart of Baotou's rare earths smelting, those environmental aspirations are blighted by pollution that can cut visibility around the main plants to a few dozen meters. The outer walls of the Huamei plant proclaim its ambitions to become the "mother ship" of Chinese rare earths production. But villagers near the rare earths plant live in a blanket of fumes, a constant reminder of how much China still allows near-unfettered industrial growth." [Ibid]

The tailings from Huamei and other nearby metals plants — that includes acids and other chemicals used to separate out the minerals — end up at a 10 square kilometer dam.The reservoir can hold 230 million cubic meters of the dark, acrid waste. That, according to a sign on its banks, is equal to 92,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

“The residents of Xinguang village said the chemicals from the dam have been seeping into the underground waters that feed their wells, crops and livestock, including fluoride. They complained of nausea, dizzy spells, arthritis, migraines, wobbly joints and slow-healing injuries." "The pollution is too much for even our crops to grow, and a lot is from the rare earths plants," Wu Leiji, a ruddy-faced farmer, told Reuters. "It's not getting any better. In fact, it's worse...Look at the kids. They're the worst off. What will all this pollution do them?" [Ibid]

A report last month in a Chinese newspaper, the Yangcheng Evening News, cited experts supporting the villagers' complaints of damaged health from rare earths and other smelting pollution. "When we boil the water to drink, this white scum forms on top and it tastes bitter," said Guo Gang, a 58-year-old farmer. "We used to grow vegetables, but now all we can grow is corn, and even the crops for that are far smaller than 10 years ago." [Ibid]

Rare earth mines often also contain radioactive elements, such as uranium and thorium. While rare earths themselves are not radioactive, they are always found in ore containing radioactive thorium and require careful handling and processing to avoid contaminating the environment. Su Wenqing, the Baotou industry official, wrote that companies there had dumped tailings, including mildly radioactive ore scrap, into local water supplies and farmland and the nearby Yellow River, "creating varying levels of radioactive pollution." [Ibid]

Visiting Baotou

Elizabeth Chang wrote in the Washington Post: ““It wasn’t until my husband and I had already shelled out thousands of dollars to visit China that I saw our destination referred to as “hideous.” Our 16-year-old daughter had unexpectedly been invited to participate in an international volleyball tournament in Inner Mongolia, with the opportunity to spend a few days touring Beijing, and we had spontaneously decided to join her... Then I started to look more closely at Baotou... and what I found was discouraging, not to mention disconcerting. Nevertheless, Darryl and I weren’t going to spend thousands of dollars and fly 7,000 miles to while away the hours between volleyball matches in a hotel room. Whatever there was to see, we vowed, we would somehow see it. City noise and singing sands. [Source: Elizabeth Chang, Washington Post, January 16, 2014]

“After a layover in Beijing...we arrived late at night in Baotou to a small crowd outside the airport, wearing bright yellow shirts and waving placards in English and Chinese. “Welcome board,” read one. The girls were dropped off at the school where the tournament would be held, and we were bused past garish neon signs to what one of the guidebooks had called a “stylish” hotel but which proved so smoky and dirty that we moved out the next day to a marginally better one.

“The walk to Baotou Number 1 Middle/High School in the morning was, literally, an assault on our senses. We were in the old part of the city, called Donghe, with worn, squat buildings, cracked sidewalks, crooked electrical poles that held drooping wires and a lot of ugly signage, given that each building needs to be advertised in both Chinese and Mongolian. The streets were full of cacophonous zooming, honking, screeching vehicles — cars, motorcycles, carts of all shapes and sizes and wheel bases — and the traffic seemed to flow according to the pattern of some near-miss dance that we didn’t know the steps to. The sky was more gray than blue, there was a strange chemical smell in the air, and the haze seemed to trap the heat. And everyone was staring at us. Apparently, this part of Baotou doesn’t see many Westerners, despite the city’s status as a leader in rare-earth industries and steel production. On the bright side: We didn’t come across anyone resembling a knife-wielding gangster, and the most dangerous thing we could do seemed to be trying to cross the street. (Actually, we soon learned, drivers routinely used the sidewalks, so we weren’t safe even there.

“On our daily walks, we would see food carts churning out pancakes; men playing checkers; people companionably working on bikes, of which there seemed to be thousands; vendors selling produce and some items we couldn’t recognize; stray dogs; diaperless toddlers; people driving by with loads of eggs or plywood and once, goldfish in bags. Our group of parents and chaperones would shop at the local grocery store for essentials such as salt and pepper and toilet paper; visit a couple of department stores for foam pads for the rock-hard beds; try in vain to find cold beer. Not a single person spoke English, but everyone was friendly and helpful.

“Still, some aspects of Baotou gave us pause. The school was behind an impressive accordion-style metal gate and everyone who entered had to show some ID. Later in the week, metal detectors were put up for tournament ticket holders. The players (even those who had parents along) weren’t allowed to leave the campus unless they were in a group and accompanied by a security guard. And when all eight teams went on a field trip, our line of buses had a police escort that nosed other vehicles out of the way.”

At the end of her stay, Chang wrote: We had “enough time to ride to another Baotou district, Kundulun, full of sleek, modern, finished high-rises, because Erica [a Chinese student they had befriended] wanted to show us her family’s new apartment. Her doting parents — abruptly summoned from their jobs to entertain some unknown Americans — would bustle home bearing soda and beer and some welcome Pizza Hut pizza. Erica would show us the furniture she had picked out, and we would all crowd onto the new couch for photographs. Like most of our experiences in Baotou, it wouldn’t be what we ever would have imagined. But it definitely wouldn’t be hideous.”

Saihan Tala Ecological Park

Saihantala Ecological Park (in Qingshan district of Baotou city) covers an area of 770 hectares and is the only wetland grassland in an urban area in all of Asia. According to the China Daily “it is a comprehensive ecological park that integrates ecology, promotion of local culture, tourism, education and scientific research. In addition, it boasts attractive and impressive Mongolian yurts, oboo, wrestling and horse racing fields.” Saihantala means “beautiful grassland” in Mongolian. The park is home to many rare birds and wild animals such as deer. . Elizabeth Chang wrote in the Washington Post: “After our rather inauthentic desert trip, we sadly concluded that a similar visit to one of the outlying grasslands wouldn’t be worth the time or expense. But Baotou is the only Chinese city that contains a grassland park, and I was determined not to leave the area without having seen an iconic Mongolian steppe. So Darryl and I joined forces with two other restless adults and took a 30-minute cringe-inducing taxi ride through the unruly sea of traffic, past several traffic circles with massive statues, to Saihan Tala Ecological Park in the Qingshan District, which seemed a tad cleaner and more modern but, alas, still lacked English speakers. We were quoted such an outrageous price to rent bikes that we walked away, until one of the workers ran up to us with a translation: “deposit.” [Source: Elizabeth Chang, Washington Post, January 16, 2014]

“The sign posted at the entrance to the park was almost poetic in its faulty English: “Every summer garden weeds characterizing a fine firm cattle and sheep like stars in the green grass, endless green prairie disseminated with the blue sky white cloud exclusive to the Great Wall.” We rode the whole way around, passing deer in a pen; a couple of Mongolian stone mounds called aobao (make a wish and walk around clockwise three times, we were advised by the sole English speaker we came across); a Mongolian-style conference center; a marsh and, yes, the grassland we had come for, the effect slightly marred by the buildings in the distance.

“Exhausted and hungry, we got to our hot pot restaurant, which I’d found online, only by showing the taxi driver the logo on my iPhone, were only able to order vegetables because of the translation app I downloaded, and spent the ride back convinced that our driver, who was taking directions via her cellphone, was going to run over someone. Still, we were quite pleased with the success of our outing. We were so pleased, in fact, that we tried to talk the tournament officials into providing transportation for the girls to visit the grassland park the following day. It might have been easier to break our daughters out of jail.”

Singing Sand Gorge

Xiangshawan (50 kilometers south of Baotou) is a 45 degree slope of sand in the Kubuqi Desert whose name translates to "Whistling Dune Bay" but the site is called "Singing Sands Gorge", "Noisy Sand Bay", "Sounding Sands", "Singing Sand Ravine", "Resounding Sand Bay", "Resonant Sand Bay", and "Resonant Sand Gorge" — all English references to the "humming", "buzzing", or "roaring" sound created by sliding on the sand. On a sunny day, which is often, when a person slides down the slope with his or her hands stirring up the sand it makes a noise like a plane flying overhead. Three miles away from here is a dense forest with yurt-hotels.

Xiangshawan is located in the Gobi Desert and is very touristy. There are resort hotels in an otherwise barren landscape. Among the activities that one can try are sand sledding, camel rides, tightrope walking, dune buggy and ATV rides, sandsurfing, sandbiking, desert volleyball and soccer and ziplines. There are swings and a playground for children. At the Guolao Theater you can watch juggling performances. There is a market and snack street and a camel caravan that leads to the Yuesha Island area.

On her visit there Elizabeth Chang wrote in the Washington Post: Resonant Sand Gorge “is a kind of desert theme park; think of golden dunes with an overlay of the tackiest aspects of Disney....The adults gazed out the windows at the impressively smooth highways and the remarkably unscenic scenery. The only interesting site we passed was the famed Yellow River, as muddy as its name would indicate. [Source: Elizabeth Chang, Washington Post, January 16, 2014]

“The Resonant Sand Gorge is named for a “singing” sound that the sand allegedly makes, which you can most readily hear when sledding down the dunes, one of the activities that our hosts strangely didn’t sign us up for (but we did get to ride the rather sad-looking camels). It was cluttered with odd accessories, including but not limited to a huge plastic “I (heart) U” tucked into the landscape; dune buggies done up like Viking ships; a theater; a train; and a hotel that looked as if it belonged in outer space. As the girls played volleyball on a beach court, before repairing to the pools, I climbed to the summit of a dune, concentrated on looking away from the people and the beach umbrellas and soothed myself with the sweeping expanse of sand and sky.”

Tibetan Monastery and Great Wall Near Baotou

Wudang Lamasery ( 70 kilometers northeast of Baotou) is the largest and best preserved Tibetan monastery in the Inner Mongolia. It covers 20 hectares and contains six temples, three Living Buddha palaces and an altar hall. 'Bada Gele Monastery' is its Tibetan name, meaning white lotus. 'Wudang” in Mongolian means 'willow'. There are many willows in the valley, thus the name. The monastery consist mainly of Tibetan-style white buildings built on a some hills according to the principles of physiognomy. [Source: Travel China Guide]

Elizabeth Chang wrote in the Washington Post: “The site I really wanted to see was the Tibetan monastery in the nearby foothills, about 45 miles away; the question was how to get there and back in time for the girls’ 4:00pm game. Taking a cab seemed out of the question. Buses would be slower. I tried one English-speaking tour guide advertised on the Internet with no success. “Finally, Erica suggested that our tiny group of three parents hire a car and driver from a travel agency. It was genius: The price turned out to be extremely reasonable, about US$100; the car was a new Mercedes SUV; and the driver was willing to make whatever stops we requested. [Source: Elizabeth Chang, Washington Post, January 16, 2014]

“So on the way to the monastery, we paused at the ruins of what is perhaps the oldest section of the Great Wall: a rammed-earth divide built during the Warring States period by King Zhao Wuling. There was a huge statue of Zhao on a rearing horse, but the wall itself, constructed in 300 B.C., was harder to find, and the signs weren’t explicit. We settled for looking at all the mounds of earth nearby, figuring that one of them had to be the right one.

“Then we went on to the 18th-century monastery, a series of whitewashed, red-edged buildings terraced into the hills, full of elaborate paintings and rugs and Buddhas of all sizes and materials. Monks in maroon robes and sneakers guarded the entryways to the nine buildings, punching tickets, instructing guests to step over the raised threshholds and whiling away the rest of the time on their cellphones.

“We had read that the once-vibrant temple usually hosted more tourists than monks, but on this day, the grounds weren’t crowded, and the sky was clear and a striking blue background for the white buildings fronted with intricate murals and draped with colorful banners and streamers. It was possible to spin every prayer wheel we passed, as Erica taught us, and imagine 1,200 monks praying together, the hills reverberating with their chants.

Ordos, China's Modern Ghost Town?

Ghinggis Khan MausoleumOrdos (700 kilometers west of Beijing) is a beautiful modern city that was built from the ground up in just five years. It is now now more filled up than it was but for some time it was described as a modern ghost town, with clean streets and charming, quite, neighborhoods but few people. The city was built to accommodate nearly one million people, for a while there only a few hundred thousand. Now there there are about a half million.

Ordos lies in the deserts of southern Inner Mongolia near coal-mining area of Shaanxi province. It is home to the world's biggest coal company and the planet's most efficient mine. Extensive coal and gas deposits below Ordos has broughy economic growth to this arid, northern outpost. The local economy grew eightfold between 2004 and 2009 while the population expanded by 20 percent.

Ordos offers some insight into what happens when planned cities don't work out as planned. Ordos had grown rich suppling coal and minerals to the rest of China. As of late 2010 the average per capita income was around US$21,000, the highest in the nation and nearly triple the national average. When people talk about Ordos they are often referring to Kangbashi. Between the 2004 and 2010 it was transformed from two villages in the grassland to cluster of grandiose buildings, including an opera house shaped like two traditional Mongolian hats, a library that resembles three massive books and museum that looks like a giant copper boulder. Many of the units in the apartments blocks were bought up by investors. The city has a capacity of 300,000 people. As of 2010 it had about 30,000.

Bill McKibben wrote in National Geographic, “Ordos may be the fastest growing city in China; even by Chinese standards it has an endless number of construction cranes building an endless number of apartment blocks. The city's great central plaza looks as large as Tiananmen Square in Beijing, and towering statues of local-boy-made-good Genghis Khan rise from the concrete plain, dwarfing the few scattered tourists who have made the trek here. There's a huge new theater, a modernist museum, and a remarkable library built to look like leaning books. Coal built this Dubai-on-the-steppe. The area boasts one-sixth of the nation's total reserves, and as a result, the city's per capita income had risen to US$20,000 by 2009. (The local government has set a goal of US$25,000 by 2012.) It's the kind of place that needs some environmentalists. [Source: Bill McKibben, National Geographic, June 2011]

In 2012, Kangbashi District was the venue for the Miss World Final. By 2017, Kangbashi had become more populated with a resident population of 153,000 and around one-third of apartments occupied. Wade Shepard wrote in Forbes: "Of the 40,000 apartments that had been built in the new district since 2004, only 500 are still on the market.

Genghis Khan Mausoleum

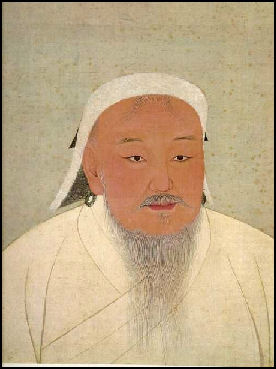

Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan Mausoleum (20 kilometers south Ordos, two hours from Baotou) is a 5.5 hectare site that honors the great Mongol leader. Built near a palace where the great Khan used to stay when he was away from his capital, it features three yurt-shaped palaces with yellow-and blue-glaze tile domes that look like samurai helmets. Leading to the gates of each of the building is a flight of steps flanked by pine trees. Yijininhuolou is a white concrete yurt built by the Chinese on the place where Genghis Khan was supposedly buried. Where he is really buried is still a mystery. Many scholars believe it is in heavily forested northern Mongolia somewhere, not so far from Russia.

The Genghis Khan Mausoleum built by Chinese government from 1954 to 1956 in a traditional Mongolian style. The site is a cenotaph, where the coffin contains no body, only headdresses and accessories as decorations. Lonely Planet calls the trip to the mausoleum “a long way to see very little.”

On her visit there, Elizabeth Chang wrote in the Washington Post: “Again, we didn’t pass much on the drive except for the “ghost city” of Ordos, where a skyline made up of partially constructed gap-windowed high-rises bears unsettling testimony to how quickly a building boom can turn to bust in China. We stopped for lunch at a small strip of shops and restaurants, where Erica ordered us traditional Mongolian food, including milk tea (too salty), fresh yogurt (amazing), dried beef (very good), a few vegetable dishes, and of course, mutton. The last was served with a plastic glove and a huge carving knife. [Source: Elizabeth Chang, Washington Post, January 16, 2014]

“The mausoleum, which the Chinese government erected in the 1950s to curry favor with the Mongolian minority, is built on a grand scale. Behind a huge white gate, and then a gigantic bronze statue of Khan, 99 steps lead to a building that looks like three gers, or yurts, with blue and gold roofs, linked together. The central yurt holds a white stone statue of Khan in the beautifully painted and tiled entryway; the wings house the so-called artifacts.

“When we moseyed into the back room, which features an altar bearing a golden statue of Khan, we came upon an extended family on a pilgrimage. The jumble of unidentifiable bony items in front of the statue, Erica found out for us, were pieces of 21 sheep, on which the relatives would dine later. Incense was lit, and various family contingents seemed to be called up for prayers or blessings as the others chatted and babies cried.

“Then a group of men, most of them wearing black felt hats, gathered at the front of the room holding blue banners draped between their upturned palms, and began singing a sutra over and over as the crowd gradually quieted. It was mesmerizing. I reluctantly let myself be pulled away, but I was grateful for a glimpse of something real and a bit ashamed that I hadn’t wanted to visit a location that clearly has deep meaning for many Mongolians.” Website: Travel China Guide (click Baotou and then attractions) Travel China Guide Admission: 110 yuan; Tel: +86-0477-8961222 Getting There: You can take a bus from Ordos bus station.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2020