BEIJING CONTROL OF ISLAM IN CHINA

Uyghur, Hui and Kazak protesting at Tiananmen Square in 1989

Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: in 2015, President Xi Jinping openly called for the “Sinicization” of Islam throughout the country, extending beyond the Uighurs to the Hui. In Xian, the hijab, gaitou in Mandarin, was banned at Shaanxi Normal University, and a Hui protest against the sale of alcohol in the Muslim Quarter — along with a nationwide call by the Hui for proper regulation of halal (qingzhen) food — was exploited on social media to provoke fears over the rise of Shariah, the legal code of Islam (jiaofa), as a threat to secular Chinese culture. [Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

The Islamic religious system under the Communist Chinese government was divided into: 1) the mosque area system, 2) "haiyi" system, 3) official school system and 4) Muslim religious communes, and so on. Among these, the mosque area system and school system are most universal. The mosque area system is the oldest and most universal religious system of Hui Islam as basically the same as the mosque community found in other Muslim areas. The "mosque area" is centered around a mosque, and includes the Muslim community living in area that worships there. Each mosque area has a Chinese-government-approved ahung (traveling Muslim teachers), "yimamu" (imam, leader), "haituibu" (coordinator), "mu'anjin" (approver) and other religious and administrative staff. In addition, there is a mosque management council (board of trustees) to manage the mosque administration. It ideally is led by an old man of noble character and high prestige who acts as the "managing squire" ("head of community" and "board chair"), who is responsible for managing the land, house property and other expense, income and expenditure of the mosque. He also makes arrangements for various kinds of activities and make decisions on the choice of ahung and other affairs of the mosque. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

A mosque is the political, economic and cultural center for Muslims in a given area. In addition to being a place of worship, it also a place for people to have meetings, discuss affairs and socialize. Mosque areas have different sizes, some are made up of less than hundreds households; others embrace several hundred or even thousands of households. But regardless of their sizes, all the mosque areas are, in theory anyway, supposed exist independently, and be equal to one another, with none being subordinate or superior to others.

See Separate Article HUI MINORITY factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF THE HUI AND HUI ISLAM factsanddetails.com ; MUSLIMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG EARLY HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG AND CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG SEPARATISM AND HUMAN RIGHTS Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG RIOTS IN 2009 Factsanddetails.com/China ; UIGHURS Factsanddetails.com/China ; HORSEMEN AND SMALL MINORITIES IN XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG, URUMQI Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG. KASHGAR Factsanddetails.com/China ; MINORITIES IN NORTHERN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; MUSLIM MINORITIES IN NORTHERN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

Websites and Sources: Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ;Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Websites and Sources on Religion in China: : United States Commission on International Religious Freedom uscirf.gov/countries/china; Articles on Religion in China forum18.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy stanford.edu ; Academic Info academicinfo.net ; Internet Guide to Chinese Studies sino.uni-heidelberg.de

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Islam: “Islam in China” by James Frankel Amazon.com; “Islam in China” by Mi Shoujiang, You Jia, et al. Amazon.com; “China and Islam: The Prophet, the Party, and Law (Cambridge Studies in Law and Society) by Matthew S. Erie Amazon.com ; Muslims “Ethnic Identity in China: The Making of a Muslim Minority Nationality” by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “Ethnographies of Islam in China” by Rachel Harris, Guangtian Ha, et al. Amazon.com; “Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “Travels through Muslim China (2005-2012): A Muslim Woman's Discovery of Chinese Mosques” by Sophie Paine Amazon.com; “Muslim China - A Photographic Recollection (2005-2012)” by Sophie Paine Amazon.com; “Dislocating China: Muslims, Minorities, and Other Subaltern Subjects” by Dru C. Gladney Amazon.com; “China's Muslims” (Images of Asia) by Michael Dillon amazon.com ; “Muslims in China” by Aliya Ma Lynn Amazon.com; History “Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China”by Jonathan N. Lipman Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “The Muslim Merchants of Premodern China: The History of a Maritime Asian Trade Diaspora, 750–1400' by John W. Chaffee Amazon.com; “The Dao of Muhammad: A Cultural History of Muslims in Late Imperial China (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by Zvi Ben-Dor Benite Amazon.com; “Muslim, Trader, Nomad, Spy: China's Cold War and the People of the Tibetan Borderlands (New Cold War History)” by Sulmaan Wasif Khan Amazon.com

Restrictions on Islam in China

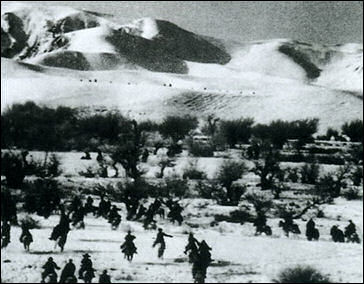

Muslim Gansu Braves during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900

There are a number of rules and restrictions regarding the practice of Islam in China. Many of them are directed at the Uighurs in Xinjiang — because some Uighurs and Uighur groups have espoused radical Islam and advocated independence for Xinjiang — not the Hui and other Muslim groups who have generally been more complaint with Beijing’s wishes.

There are severe restrictions of making the pilgrimage to Mecca. Only a few are allowed to go. Many more want to go and resent the fact they can’t. In many places the Chinese have banned muezzins — the loudspeakers that call the faithful to prayer. Instead the call to prayer is performed the old fashion way by a man who shouts at the top of his lungs from the roof a mosque. Schools that train Muslim clerics are carefully monitored and students have to undergo thorough background checks before they are admitted. Longtime clerics have been forced to enroll in Chinese patriotic programs and undergo annual licencing procedures. Many are on Beijing’s payroll.

In some places Muslims are prohibited from fasting and gathering at mosques during Ramadan. There are also rules prohibiting students from entering Muslim schools if they are under 18 or have not completed their education at regular Chinese secondary schools. Public schools in some Muslim areas insist that students eat during Ramadan. If they don’t eat they are disciplined. In Kasghar, tea kettles have been seized from students out of concern the students might use them for ritual morning ablutions before Muslim prayers.

Muslim are only supposed to worship at mosques that have been sanctioned by the state-supported Chinese Islamic Association. In some places Friday prayers are limited to 30 minutes with sermons scripted by Beijing. Mullahs who say something the government doesn’t like risk getting thrown in jail for 10 years. Government employees are not allowed to enter mosques and clerics at the mosques are supposed to report those that do. If workers are caught going to mosques they risk losing their jobs.

In 1995, the Chinese Islamic Association decreed: "No scripture studies or Arabic classes are to be held without permission." Signs and banners hung outside mosques in Hotam, Kashgar and other cities in Xinjiang read: “Completely aided by the Communist Party’s religious policy. Actively lead religion towards a just socialist society.” Polygamy was outlawed by the Communists shortly after they came to power in 1949.

Repression of Islam in China

As part of Beijing's campaign against Muslim separatism and terrorism, young people are banned from mosques, foreign Muslims are banned from meeting local imams and mosques are routinely prohibited from issuing the call to prayer. Religious material has been seized and hundreds of mosques and Koranic schools have been shut down. Muslims have been arrested for preaching illegally and translating the Koran into local languages. Imam have been sent to re-education classes. Some Muslims complain that if they want to get ahead or land a good job they have to renounce their religion or at least not be so public about their religion.

The Communist government closely monitors religious activity and worries that mosques and other houses of worship might become centers for anti-government agitation. Mosques are sometimes empty because Muslims fear being blacklisted for going there. Many mosque are infiltrated by informers. In response to repression a number of underground mosques have opened up. Many believe these are more likely to be breeding grounds for Islamic extremism than ordinary mosques.

According to the U.S. State Department: In the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR, the government cited concerns over “separatism, religious extremism, and terrorism” as a pretext to enact and enforce repressive restrictions on religious practices of Uyghur Muslims. Authorities often failed to distinguish between peaceful religious practice and criminal or terrorist activities. It remained difficult to determine whether particular raids, detentions, arrests, or judicial punishments targeted those seeking political goals, the right to worship, or criminal acts. [Source: “International Religious Freedom Report for 2013 China”, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, U.S. Department of State, state.gov /|]

Hui Tungan rifleman fighting for the Communists

There was increased pressure in official campaigns to dissuade women from wearing religious clothing and men from wearing beards. Officials singled out lawyers and their families in these campaigns. The Xinjiang judicial affairs department website posted a statement saying, “Lawyers must commit to guaranteeing that family members and relatives do not wear burqas, veils, or participate in illegal religious activities, and that young men do not grow long beards.” Authorities in Bulaqsui reportedly kept “stability maintenance” registers that included information such as whether female Muslims wore a veil. Uyghur sources also reported recipients of public welfare stipends were asked to sign a pledge not to cover their faces for religious reasons. Uyghurs in Kashgar and Turpan reported officials interfered with fasting during Ramadan. Hui Muslims in Ningxia, Gansu, Qinghai, and Yunnan provinces engaged in religious practice with less government interference than did Uyghurs. /|\

Authorities continued their “patriotic education” campaign, which in part focused on preventing illegal religious activities in XUAR. Human rights organizations asserted in some instances security forces shot at groups of Uyghurs in their homes or during worship. Authorities typically characterized these operations as targeting “separatists” or “terrorists.” The government reportedly sought the forcible return of ethnic Uyghurs living outside the country, many of whom had sought asylum for religious persecution. In some cases third countries complied with Chinese requests for forcible refoulementof Uyghur asylum-seekers. There were reports of imprisonment and torture of Uyghurs who were returned. The government’s control of information coming out of the XUAR, together with its increasingly tight security posture there, made it difficult to verify the conflicting reports. /|\

In the XUAR, tension between Uyghur Muslims and ethnic Han continued, as officials strengthened their enforcement of policies banning men from growing long beards, women from wearing veils that cover their faces, and parents from providing their children with religious education. Many hospitals and businesses would not provide services to women wearing veils. In September a Uyghur Muslim was reportedly beaten for praying on a bus and later detained by authorities. Tensions also continued among ethnic and religious groups in Tibetan areas, particularly between Han and Tibetans, and, in some areas, between Tibetans and Hui Muslims. /|\

Repressions is less severe in Hui areas in Ningxia than Uighur areas in Xinjiang. The Muslim schools there are full of eager students; Ningxia University offers classes in Arabic; and kindergarten students take classes in Islam. Some of the schools there are financed by Arab countries in the Middle East that supply China with oil and gas. In Qinghai and Gangsu, Hui Muslims go by Muslim names, eat at restaurants that refuse to sell alcohol or pork, openly express their fondness for Osama bin Laden and call the Chinese “godless people.” In some vilages most women cover their heads and most men wear Muslim-style skull caps, have beards and greet each other in Arabic. Dru Gladney, an expert on Chinese Muslims at the University of Hawaii, told Reuters, “In places like Qinghai and Gansu, where Islam is less politicized, the government is more open and more relaxed. Particularly in very poor areas, there is a lot of flexibility.”

See Chinese Crackdowns in Xinjiang, Xinjiang, Minorities

Chinese Government Restrictions on the Hajj, Ramadan and Islamic Schools

Ma Jia Jun Army

According to the U.S. State Department: Media reported Muslims could apply online or through local official Islamic associations to participate in the Hajj. According to media reports in the country, approximately 11,800 Muslim citizens participated in the Hajj in the fall including 2,223 individuals from Ningxia; 2,228 from Gansu Province; 1,310 from Yunnan Province; and 236 from the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. These figures included Islamic association and security officials sent to monitor Muslim citizens and prevent unauthorized pilgrimages. Figures were not available for pilgrims from the XUAR. [Source: “International Religious Freedom Report for 2013 China”, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, U.S. Department of State, state.gov /|]

According to reports, Hajj pilgrims paid RMB 42,000 ($6,938) to participate, which included roundtrip flights, meals, and accommodations. Uyghur Muslims reported difficulties taking part in state-sanctioned Hajj travel due to the inability to obtain travel documents in a timely manner and difficulties in meeting criteria required for participation in the official Hajj program run by the Islamic Association of China. The government limited the ability of Uyghur Muslims to make private Hajj pilgrimages outside of the government-organized program. /|\

Authorities in the XUAR imposed strict controls on religious practices during Ramadan. The government barred teachers, professors, civil servants, and CCP members from fasting and attending religious services at mosques. Local authorities reportedly fined individuals for studying the Quran in unauthorized sessions, detained people for “illegal” religious activities or carrying “illegal” religious materials, and stationed security personnel in and around mosques to restrict attendance to local residents. Authorities reportedly hung Chinese flags on mosque walls in the direction of Mecca so prayers would be directed toward them. In the XUAR government authorities at times restricted the sale of the Quran. In March authorities in Kashgar reportedly detained a Uyghur Muslim without charge for 63 days for selling the Quran and study aids. /|\

There were widespread reports of prohibitions on children participating in religious activities in various localities throughout the XUAR, but observers also reported seeing children in mosques and at Friday prayers in some areas of the region. Islamic schools in Yunnan Province were reluctant to accept ethnic Uyghur students out of concerns they would bring unwanted attention from government authorities and negatively affect school operations. Kunming Islamic College, a government-affiliated seminary, posted an official announcement stating it was open only to students from Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou provinces or from Chongqing municipality. /|\

Officials in the XUAR, however, require minors to complete nine years of compulsory education before they can receive religious education. According to media reports, authorities in the Xinjiang town of Yining bar minors under the age of 18 from entering the city’s mosques. The law imposes penalties on adults who “force” minors to participate in religious activities. The teaching of atheism in schools is allowed. /|\

Curbs During Ramadan After the Riots in Xinjiang

In September 2009, after the riots in Urumqi, local governments in Xinjiang imposed strict limits on religious practices during the traditional Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, according to the Web sites of four of those governments. The rules include prohibiting women from wearing veils and men from growing beards, as well as barring government officials from observing Ramadan. One town, Yingmaili, requires that local officials check up on mosques at least twice a week during Ramadan. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, September 8, 2009]

struggle session in Qinghai in the 1950s

The local governments administer areas in the western part of Xinjiang that have large numbers of Muslim Uighurs. The limits on religious practices put in place by local governments appear to be part of the broader security crackdown. The areas affected by the new rules are near Kuqa, a town struck by multiple bombings.

The Web site of the town of Yingmaili lists nine rules put in place to maintain stability during Ramadan. They include barring teachers and students from observing Ramadan, prohibiting retired government officials from entering mosques and requiring men to shave off beards and women to doff veils. Mosques cannot let people from outside of town stay overnight and restaurants must maintain normal hours of business. Because of the sunrise-to-sunset fasting, many restaurants would normally close during daytime for Ramadan.

In nearby Xinhe County, the government has decreed that Communist Party members, civil servants and retired officials must not observe Ramadan, enter mosques or take part in any religious activities during the month. Worshipers cannot make pilgrimages to tombs, so as to avoid any group event that might harm social stability, according to the Xinhe government’s Web site. In addition, children and students cannot be forced to attend religious activities, and women cannot be forced to wear veils.

County rules also emphasize the need to maintain a strict watch over migrant workers and visitors from outside the county. Companies and families that have workers or visitors from outside the county are required to register the outsiders with the nearest police station and have them sign an agreement on maintaining social stability. Shayar County, which includes the town of Yingmaili, said on its Web site that migrants must register with the police, and that any missionary work by outsiders was banned.

Efforts by Beijing to Make Muslims Eat During Ramadan

In the aftermath of violent protests in 2011 by Uighurs, authorities have deepened their campaign against religious practices — particularly during Ramadan. Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “At a teachers college in far northwestern China, students were irritated to find that their professors were escorting them to lunch last month — an odd occurrence since they were more than capable of finding the cafeteria themselves. There was an ulterior motive, students told travelers who recently visited the city of Kashgar: The college wanted to make sure that the students, most of them Muslims, were eating rather than fasting in daylight hours during the holy month of Ramadan. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, September 11, 2011]

a Hui in Yunnan “Then, something even stranger happened, the students said. When Ramadan ended late last month, launching the three-day Eid al-Fitr feast, all the restaurants and the cafeteria on campus were shut down. Students were barred from leaving the campus. On the next two days of the holiday, the cafeteria was open, but the students were locked in, unable to leave to celebrate with their families. "It was totally backwards," complained a 20-year-old Muslim student who was forced to skip the holiday.

For years, China has restricted observance of Ramadan for Communist Party members and government cadres. On one website for an agricultural bureau, for instance, employees were reminded "not to practice any religion, not to attend religious events and not to fast."

Residents of Xinjiang province say that Chinese policies regarding Ramadan have become steadily more draconian over the years. "It has been bad since 1993 and it is getting worse," said Tursun Ghupur, 33, who comes from Kashgar but has been living in Beijing. "Usually for ordinary people it is OK. You can pray and you can observe Ramadan. But if you go to school and have a job with the government, you can't be religious."

Political scientists say the government's strategy is likely to backfire. "Particularly with the government crackdown on religion in Xinjiang, this has made more people see religion as a form of resistance rather than personal piety," said Dru Gladney, a professor of anthropology at Pomona College specializing in Central Asia. "From the authorities' standpoint, it's really counterproductive."

At the very least, the restrictions on Ramadan undermine personal relations between Uighurs and Han Chinese. The Kashgar doctor related an incident involving his nephew, a student at a junior high school. During the holiday, the boy was given a piece of candy by his teacher, who is Han Chinese. "I'm doing well in school. The teacher likes me. She gave me candy," the boy told his father late that day. The father scoffed at the explanation. "She is only trying to tell if you're fasting for Ramadan."

Restaurants Forced to Stay Open During Ramadan

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In Kashgar the local Communist Party in Kasghar ordered restaurants to remain open during the day during Ramadan, even though chefs and most of their potential customers were fasting. Failure to keep their doors open made restaurants subject to fines of up to $780, the equivalent of several months' salary, so restaurateurs in the far northwestern Chinese city made token gestures to appear open, assigning one waiter to sit in the doorway and a chef to make a single dish that would be either eaten cold at night or discarded.

In Kashgar, across from the Id Kah Mosque, the largest in China, travelers described a bored teenage waiter in a Muslim skullcap sitting in the doorway of a darkened restaurant looking out onto the dusty sidewalk as if waiting for the customers he knew wouldn't come. Along the entire strip, restaurants were similarly unlit and empty, with none of the usual smells of roasting lamb wafting from the kitchens.

"They just offer what they can to avoid trouble," said a doctor in his late 20s, who asked not to be quoted by name for fear of retaliation. He described the compromise at one of his favorite restaurants, where the chef made only rice pilaf. "The chefs can't even taste the food to make sure it is delicious."

The policy extended deeper into Xinjiang province than just Kashgar. In Aksu, 250 miles to the northeast, the municipal website warned that restaurant owners "who close without reason during the 'Ramadan period' will be severely dealt with according to the relevant regulations."

Anti-Muslim Sentiments in China

Ant-Japanese Muslim fighters

Wai Ling Yeung wrote in China Change in 2016: “Recently a video of a 5-year-old Hui Muslim kindergarten pupil from Gansu province reciting verses from the Qur’an went viral on China’s social media, attracting almost unanimous condemnation from presumably Han Chinese netizens. At a discussion forum, for example, several comments labelled the preaching of religion to children as “evil cult” behavior. They called for netizens to “say no to evil cults and to stop evil cults from invading schools.” Others questioned why schools allowed children to “wear black head scarves and black robes as if they’re adults.” They also expressed support for legislation that “set an age limit to religious freedom.” One comment went as far as asking all Hui Muslims to move to the Middle East. “In my opinion, their religion has no part in Chinese civilization. It belongs somewhere else. I hope they will all leave.” [Source: Wai Ling Yeung, China Change, May 13, 2016]

“It was subsequently discovered that the aforementioned video was initially posted on YouTube in 2014. It makes one wonder why the video has suddenly emerged and become popular, and whether the “public anger” it has generated is indeed genuine and spontaneous. Provincial education authorities subsequently ordered a strict adherence to a ban on religion in schools. On Twitter, when Ismael, a Hui Muslim poet and blogger from Shandong, a coastal province, defended Hui Muslims’ right to freedom of religion, his Twitter account was invaded by a torrent of abusive responses to his recent tweets (here, here and here for just a few examples). As someone who re-posted Ismael’s tweets, I bore witness to this unfortunate episode of cyberbullying on Twitter; I later learnt that Ismael had sustained even more serious abuses at other Chinese online fora.

“In addition to the video of the 5-year-old reciting the Qur’an, two other events in particular have caught the attention of many observers: Unspecified allegations of ‘Arabization,’ in rather hysterical language, were made against Xinjiang, as well as the Hui autonomous region of Ningxia and Linxia, Gansu , during a high profile religious conference held in April 2016. Rumours surrounding the sudden dismissal of Wang Zhengwei in April as the Chair of State Ethnic Affairs Commission contain allegations of his unspecified involvement in new mosque building projects, promoting Arabic language education, and in regulating the preparation of Halal food. Wang is of Hui ethnic heritage.

“According to Ismael, anti-Muslim sentiment is fast spreading among mainstream bloggers as censors at Weibo are working overtime deleting accounts of known Hui Muslims, in an attempt to prevent them from defending their religion. “This is not London, where a Muslim can become a human rights lawyer. Here in China, human rights lawyers are in jail. We don’t have media that will speak for us,” Ismael wrote to me. “When anti-Muslim hooligans smear our religion on the internet, and if we dare to defend ourselves, our accounts will be deleted. Sometimes the police will turn up at our doorsteps.”

Chinese Newspaper Claims Islamists Want to Ban TV and Singing

Muslim girls in Fujian

In 2013, Reuters reported: Islamists in China's far western region of Xinjiang are seeking to ban television, singing and other forms of entertainment, a newspaper said, adding that "religious extremism" was a disaster facing the area. China has stepped up its rhetoric against what it says is a threat the country faces from Islamist militants since an incident last month in which a vehicle ploughed into tourists on the edge of Beijing's Tiananmen Square, killing the three people in the car and two bystanders. China d has reacted angrily to suggestions that it was because of frustration and anger over government repression of the region's Muslims. [Source: Reuters, November 29, 2013]

“In a front-page piece in the official Xinjiang Daily, Yusufujiang Maimaiti, the head of the region's employment bureau, said "forces" were furthering their "evil aims" by seeking to foist extremist beliefs on the region's Muslims. "Religious extremist forces ... don't allow people to sing or dance, they incite them to disobey the government, to not use marriage certificates and I.D. cards. They prevent them from watching television, films, and listening to the teachings of patriotic religious leaders," he wrote.

He did not identify the extremists but said they were"distorting and falsifying" religious doctrine with a creed of opposing anyone who was different from them culturally or religiously. "Religious extremism is the biggest disaster facing the development and long-term peace and stability of Xinjiang," he added. "Our battle against extremism is undeniable and unavoidable."

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, CNTO, Nolls Mongabey

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2022