EVOLUTION OF THE HUI

Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: “ Hui is an inexact label for a people that comprises many sects, scattered across the country, with no language of their own.What they share is an ancestry often traced back to the first Muslim Arabs and Persians to enter China during the Tang Dynasty (618-906), as merchants and, in the northwest, as mercenary warriors sent by the Abbasid Caliphate (A.D. 750-1258) to help quash the An Lushan Rebellion. [Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

"In the early years of Islam, Muslim traders mostly bypassed the Silk Road in favor of crossing the Indian Ocean to the ports of southeastern China, where they were designated fan ke — “foreign guests” — a foreignness that persisted even for their children by Chinese wives: tusheng fan ke, “native-born foreign guests.” As the British Sinologist Michael Dillon has chronicled, Islam didn’t truly take root in the country until five centuries later, when the Mongol leader Genghis Khan and his successors conquered almost a quarter of the globe and forcibly marched as many as three million Muslim soldiers, along with untold numbers of Muslim artisans, scientists and scholars, from Central Asia to China. Under the rule of his grandson Kublai Khan, their descendants intermarried with the locals and were accepted as Chinese, becoming known as the Hui.[Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

Muslims that evolved into Huis were called "aboriginal guests" in Tang and Song dynasties. They spread to the Central Plains of China and were entrenched there. Over the centuries, the Huis have absorbed Han Chinese, Mongolians and Tibetans that converted to Islam as well as Muslim Uyghurs. In the 13th century, after the Mongols took over the Silk Road and allowed relatively free travel throughout Central Asia, a large number of Muslims from Persia, Arabia, and Central Asia immigrated through the Silk Road land routes and established themselves in various parts of China, in the northwest, the Central Plains, Yunnan and the lower reaches of the Yangzi River. It was at this time that they received the name Hui. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

The Hui emerged and grew very fast. From the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), many Uyghurs, Mongols and Han Chinese origin were assimilated to the Hui due to intermarriage and religious affiliation. In the meantime, there were also many Hui assimilated to the Chinese for similar reasons. The Hui nationality came into being as a result of merging of Hui of different origins. Although the growth of the Hui was largely due natural increases some of it is attributed Hui, Muslim and Han Chinese marriage practices and rules. Hui women were almost always forbidden to marry non-Hui, but Hui men could marry Han or other non-Hui women who were willing to convert to Islam. When Hui men married Han women, the Han women changed their registration with the government to “Hui," and the children of the marriage were Hui. Islam has a strict rules that prevent conversion thus it was considered impossible for a Hui to become Han, while the reverse was possible. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

See Separate Articles: HUI MINORITY factsanddetails.com ; HUI LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com; MUSLIMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com CONTROL AND REPRESSION OF ISLAM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China's Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects” by Michael Dillon Amazon.com ;“Hui Muslims in China” by Gui Rong, Hacer Zekiye Gonul, Zhang Xiaoyan (2016) Amazon.com; “The Muslim Midwest in Modern China: The Tale of the Hui Communities in Gansu (Lanzhou, Linxia, and Lintan) and in Yunnan (Kunming and Dali)” by Raphael Israeli Amazon.com; Holy Journey for Soul: The Huis” by Lin Yu Amazon.com; History: “Islamic Thought in China: Sino-Muslim Intellectual Evolution from the 17th to the 21st Century” by Jonathan N Lipman Amazon.com; “The Panthay Rebellion: Islam, Ethnicity and the Dali Sultanate in Southwest China, 1856-1873 by David Atwill Amazon.com

Origin of the Hui

Arabic plaque at the Great Mosque in Xian

The Hui are descendants of Han Chinese whose ancestors converted to Islam and Muslim traders from the Arab, Persian and Turkish empires and the Middle East who came to China during the Tang dynasty (618-907), when Islam was introduced to China. Some of the first arrivals made it Changan (present-day Xian), the Tang Dynasty capital and starting point of the Silk Road. The Great Mosque of Xian was built on A.D. 742. Most Hui can trace their descent line to a “foreign" ancestor.

Islam first appeared in China in the 7th century in the Tang Dynasty (618-907), following the emergence of Islam in Arabia in 610. Arab and Persian traders, soldiers and Sufi saints played a significant role in the transmission of Islam to Asia. Persian and Arab traders first settled in the southeastern coast of China, Canton (Guangzhou,) Xiamen, Quanzhou, Yangzhou, and some of them married local Chinese. They were few in number are were largely ignored by local officials during Tang and Song Dynasties (618-1279). [Source: Ali Osman Ozkan, Fountain magazine, April 2014]

Some Islamic Arabs and Persians who came to China to trade later became permanent residents of such cities as Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Hangzhou, Yangzhou and Chang'an (today's Xi'an). These people, referred to as "fanke" (guests from outlying regions), built mosques and public cemeteries for themselves. Some married and had children who came to be known as "tusheng fanke," meaning "native-born guests from outlying regions."

Early History of the Hui

The formation of the Hui nationality is unique in that it was created by Chinese that converted to Islam, a process that was long and complex. With other Muslim minorities in China the situation was completely different. For Uyghurs, Kazaks, Kyrgyz and other Muslim nationalities in Xinjiang and northern and west China : they formed as ethnic groups first and then converted to Islam. ~

The Hui developed into a distinct identity in the Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties. The term "Hui" was first used in the Yuan dynasties to describe of various peoples from Central Asia. The name is an abbreviation for "Huihui," which first appeared in the literature of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). It referred to the Huihe people (the Ouigurs) who lived in Anxi in the present-day Xinjiang and its vicinity since the Tang Dynasty (618-907). They were actually forerunners of the present-day Uyghurs, who are totally different from today's Huis or Huihuis. [Source: China.org]

During the early years of the 13th century when Mongolian troops were making their western expeditions, group after group of Islamic-oriented people from Middle Asia, as well as Persians and Arabs, either were forced to move or voluntarily migrated into China. As artisans, tradesmen, scholars, officials and religious leaders, they spread to many parts of the country and settled down mainly to livestock breeding. These people, who were also called Huis or Huihuis because their religious beliefs were identical with people in Anxi, were part of the ancestors to today's Huis. |

During the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), these people became part of the Huihuis, who were coming in great numbers to China from Middle Asia. The Huihuis of today are therefore an ethnic group that finds its origins mainly with the above-mentioned two categories, which in the course of development took in people from a number of other ethnic groups including the Hans, Mongolians and Uyghurs. |

The Hui nationality also absorbed Jews that immigrated into China in the Song dynasty and the Filipinos that immigrated into Dezhou and Shandong at the beginning of the 15th century. In the Yuan dynasty, some Jews in China were called "Shuhu Huis" because their Jewish religious customs—such as circumcision and and not eating pork—were similar as those of the Muslim Huis, Because the scarves worn by these Jews when they participated in religious activities was pale blue, they were also called "blue hat Huis" or "pale blue Huis" in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Because these Jews were linked by the Han Chinese with Muslim Huiss, the two groups intermarried and their offspring were mostly absorbed into the Muslim Hui community. ~

Dong Fuxiang victory

Hui in Imperial China

In the Tang and Song Dynasties when the Hui were developing, proto Huis from Central Asia for the large part spoke Turkic languages laced with Persian and Arabic words and phrases. Those inside China used Chinese languages. Over time Chinese gradually became the common language used by all Huis people. Rather than settling in one area and making that their homeland there—perhaps because the places they came from were so dry, harsh and inhospitable— the Hui have traditionally migrated to wherever opportunity beckoned them. Because their distribution is widely scattered and their concentrations in a given area are relatively small. Islam is the main thing that has held them together. Otherwise they are mostly a minority that lives side by side with other ethnic groups.

It is generally acknowledged that Huihui culture began mainly during the Yuan Dynasty. Warfare and farming were the two dominant factors of this period. During their westward invasion, the Mongols turned people from Middle Asia into scouts and sent them eastward on military missions. These civilians-turned-military scouts were expected to settle down at various locations and to breed livestock while maintaining combat readiness. They founded settlements in areas in today's Gansu, Henan, Shandong, Hebei and Yunnan provinces and the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. They later were joined by more scouts sent from the west. As time went by they became ordinary farmers and herdsmen. Among the Islamic Middle Asians, there were a number of artisans and tradesmen. The majority of these people settled in cities and along vital communication lines, taking to handicrafts and commerce. Because of these activities a common economic life began to take shape among the Huihuis. Scattered as they were, they stuck together in relative concentration in settlements and around mosques which they built. This has been handed down as a specific feature of the distribution of Hui population in China. [Source: China.org |]

The Huihui scouts and a good number of Huihui aristocrats, officials, scholars and merchants sent eastward by the Mongols were quite active in China. They exercised influence on the establishment of the Yuan Dynasty and its military, political and economic affairs. The involvement of Huihui upper-class elements in the politics of Yuan Dynasty in turn helped to promote the development of Huihuis in many fields. |

Generally speaking, the social position of Huihuis during the Yuan Dynasty was higher than that of the Hans. Nevertheless, they were still subjected to the oppression of Yuan rulers. After going through the hardships of their eastward exodus, they continued to be in the hands of various Mongolian officials, functioning either as herdsmen or as government and army artisans. A fraction of them even were allocated to Mongolian aristocrats to serve as house slaves. Being people who came to China from places where social systems, customs and habits differed from those in the east, the Huihuis began to cultivate their own national consciousness. This was caused also by their relative concentration with mosques as the center of their social activities, by their increasing economic contacts with each other, by their common political fate and their common belief in the Islamic religion. |

Chinese Muslim cavalry between 1929 and 1949

It was during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) that the Huihuis began to emerge as an ethnic group. Along with the nationwide restoration and development of the social economy in the early Ming Dynasty years, the distribution and economic status of the Huihui population underwent a drastic change. The number of Huihuis in Shaanxi and Gansu provinces increased as more and more Huihuis from other parts of the country submitted themselves to the Ming court and joined their people in farming. |

Other factors contributed to their dispersion: industrial and commercial exchanges, assignment of Huihui garrison troops to various areas to open up wasteland and grow food grain, nationwide tours by Huihui officials and scholars, and especially the migration of Huihuis during peasant uprisings. They still managed, however, to maintain their tradition of concentration by setting up their own villages in the countryside or sticking together in suburban areas or along particular streets and lanes in cities. The dislocation of military scouts dating from the Yuan Dynasty had enabled the Huihuis to extricate themselves gradually from military involvement and to settle down to farming, breeding livestock, handicrafts and small-scale trading. Thus they established a new common economic life among themselves, characterized by an agricultural economy. |

During the initial stage of their eastward exodus, the Huihuis used the Arab, Persian and Han languages. However, in the course of their long years living with the Hans, and especially due to the increasing number of Hans joining their ranks, they gradually spoke the Han language only, while maintaining certain Arab and Persian phrases. Huihui culture originally had been characterized by influences from the traditional culture of Western Asia and assimilation from the Han culture. However, due to the introduction of the Han language as a common language, the tendency to assimilate the Han culture became more obvious. The Huihuis began to wear clothing like the Hans. Huihui names were still used, but Han names and surnames became accepted and gradually became dominant. |

Contribution by Hui to Chinese Civilization

Since the Yuan and Ming dynasties, a number of Huis have distinguished themselves in culture, science warfare and exploration. Famous Hui historical figures have included Zhamaluding, Sadula, Gao Kegong, Ding Henian, Zheng He, Li Zhi and Hai Rui. Hui scholars and scientists made outstanding contributions to China in introducing and spreading the achievements of Western Asia in astronomy, calendars, medicine and a number of other academic and cultural developments. [Source: China.org |]

During the Yuan Dynasty, Jamaluddin (Jamal al-Ding), a 13th century astronomer made an armillary sphere, and azimuth compass and celestial globe and supervised the compilation of “The Illustrated Geological Annals.” Hecompiled a perpetual calendar and produced seven kinds of astroscopes including the armillary sphere, the celestial globe, the terrestrial globe and the planetarium. Alaowadin and Yisimayin led the development of a mechanized way of shooting stone balls from cannons, which exercised an important bearing on military affairs in general; the architect Yehdardin learned from Han architecture and designed and led the construction of the capital of the Yuan Dynasty, which laid the foundation for the development of the city of Beijing. |

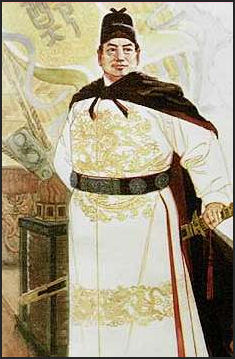

Hui Tungan rifleman fighting on the Communist side During the Ming Dynasty, the Hui navigator Zheng He led massive fleets in making as many as seven visits to more than 30 Asian and African countries in 29 years. This unparalleled feat served to promote the friendship as well as economic and cultural exchanges between China and these countries. Zheng He was accompanied by Ma Huan and Ha San, also of Hui origin, who acted as his interpreters. Ma Huan gave a true account of Zheng He's visits in his book Magnificent Tours of Lands Beyond the Ocean, which is of major significance in the study of the history of communication between China and the West. Hui scholar Li Zhi (1527-1602) of Quanzhou in Fujian Province was a well-known progressive thinker in Chinese ideology history. |

A number of outstanding politicians emerged among the Huis. Sayyid Ajall Sham Suddin (1211-1279) of early Yuan Dynasty was one of them. During his late years when he was serving as governor of Yunnan Province, he laid stress on agriculture, setting up special areas for peasants to reclaim wasteland and grow food grain. He advocated the harnessing of six rivers in Kunming, capital of the province; established communication posts extensively for couriers to change horses and rest; initiated teaching in Confucianism and made strong efforts in harmonizing relations among various nationalities. All these benefitted political, economic and cultural developments in Yunnan, helping to bring closer relations between the province and the central government. |

Hai Rui (1514-1587), a politician of the Ming Dynasty, was upright throughout his life. He had the courage to remonstrate with Emperor Jiajing about his fatuousness and arbitrariness that brought the nation and the people to calamity. Hai also lashed out at what he considered to be the evils of the court and inept ministers. Later during his term of office as roving inspector directly responsible to the emperor and as chief procurator of Nanjing, Hai enforced discipline, redressed mishandled cases and checked local despots in a successful attempt to boost public morale. Since the Yuan and Ming dynasties, a great number of established Hui poets, scholars, painters and dramatists emerged. These included Sadul, Gao Kegong, Ding Henian, Ma Jin, Ding Peng and Gai Qi.

Hai Rui: the Honest and Upright Hui Official

Hai Rui (1514 to 1587) was a famous Hui and official in the Ming dynasty. His name has come down in history as a model of honesty and integrity in office and he reemerged as an important historical character during the Cultural Revolution. Hai Rui, whose great-grandfather married an Arab and subsequently adopted Islam, was born in Qiongshan, Hainan, where he was raised by his mother (also a Muslim, from a Hui, family). Unsuccessful in the official examinations, his official career started in 1553, when he was aged 39, with a humble position as clerk of education in Fujian province. [Source: Cultural China \=/]

Hai Rui

At the beginning of his career, Hai Rui was appointed the post of Fujian Nanping Jiaoyu, then was promoted as the magistrate of Chun'an county in Zhejiang and Xingguo county in Jiangxi, he pursued the policy of measuring land carefully and equalizing the tax, and reversed many unjust cases, cracked down corrupt officials, and enjoyed the ardent support of the people. In the 45th year of Jiajing emperor, he was promoted as president of Yunnan department of the Board of Revenue. He criticized that Shizong emperor for practicing witchcraft, living in luxury and neglecting his duties. For this he was thrown into prison. After Shizong died, he was released. In the 3rd year of Longqing emperor (1569), he was promoted as vice Qiandu Yushi. As before, he punished corrupt officials, cracked down on despots, dredged and built river channels, constructed irrigation works and forced corrupt officials to work in the fields to people, and thus became known as "Hai the Clear Sky". After that, he was purged and stayed at home idle for 16 years. In the 13th year of Wanli emperor (1585), he was appointed to an important position again, the vice president of the Board of Civil Office in Nanjing, and again worked diligently to strictly punish corrupt officials and clampdown on the practice of accepting bribes. Hai Rui died in office two years later. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Hai Rui built his reputation on uncompromising adherence to an upright morality, scrupulous honesty, poverty, and fairness. This won him widespread popular support but made him many enemies in the bureaucracy. When he impeached the Jiajing Emperor himself in 1565 and was initially sentenced to death but escaped that fate perhaps because of his reputation and popularity. Throughout his life, Hai Rui was known as an honest and incorruptible official, upright and above flattery, and was deeply respected and venerated by the people. It was said, when hearing the grievous news of his death, the local ordinary people were filled with deep sorrow and felt like they lost a family member. When his bier was transported back to his hometown by the waterway in Nanjing, the banks of the Yangtze River were filled with people to see him off. Many ordinary people places his portrait in their homes. Dramas and literary works inspired by him include The Big Red Gown of Lord Hai and The Small Red Gown of Lord Hai, and Hai Rui Submitted a Memorial to the Emperor.

Hai Rui's fame lived on in modern times. An article entitled "Hai Rui Dismissed from Office", written by Communist Party official Wu Han in 1959 and later made into a Peking Opera play, was interpreted by Gang of Four member Yao Wenyuan as an allegorical work with the honest moral official Hai Rui representing disgraced official Peng Dehuai, who was purged by Mao for his outspoken criticism of the Great Leap Forward, and corrupt emperor representing Mao Zedong. The November 10, 1965 article in a prominent Shanghai newspaper, "A Criticism of the Historical Drama 'Hai Rui Dismissed From Office'", written by Yao, is widely seen as the spark that ignited the Cultural Revolution. During the Cultural Revolution, the grave of Hai Rui was destroyed but it has since been rebuilt. \=/

Zheng He

Zheng He (also known as Chêng Ho, Cheng Ho, Zheng Ho, and the Three-Jewel Eunuch) was a Chinese navigator without a penis or a set of testicles whose achievements as an explorer rank with those of Columbus and Magellan but who has been largely forgotten because his travels had little impact on history. [Source: Frank Viviano, National Geographic, July 2005]

Zheng He (also known as Chêng Ho, Cheng Ho, Zheng Ho, and the Three-Jewel Eunuch) was a Chinese navigator without a penis or a set of testicles whose achievements as an explorer rank with those of Columbus and Magellan but who has been largely forgotten because his travels had little impact on history. [Source: Frank Viviano, National Geographic, July 2005]

Zheng Ho (pronounced “jung huh”) was a Hui. He embarked from China with a huge fleet of ships and journeyed as far west as Africa, through what the Chinese called the Western seas, in 1433, sixty years before Columbus sailed to America and Vasco de Gama sailed around Africa to get to Asia. Zheng also explored India, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, and Arabia with about 75 times as many ships and men as Columbus took with him on his trans-Atlantic journey.

A stelae erected by Zheng He in Fujian in China reads: “We...have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising sky high, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails, fully unfurled like clouds day and night, continue their course [as quickly as] a star, traversing those savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare.”

Zheng He was very tall and a man of incredible ambition. Some descriptions say he stood seven feet tall, possessed a waist that was five feet in circumference and had “a voice as loud as a huge bell." He was a devout Muslim and supposedly earned his nickname “Three Jewel Eunuch” for the gems he gave out as gifts. His lack of recognition as a great explorer is partly because the Chinese never went to any length to declare he was a great explorer.

See ZHENG HE AND CHINESE EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

"Great Scattering and Small Concentration" of the Hui

"Great scattering and small concentration" is the distinctive character of the distribution of the Hui nationality. This character first took shape early “aboriginal guests” came from the east. During the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties, Huis soldiers' helped open up frontier areas in the west and the south. The Hui also grew crops, worked as trader and provided officials and scholars. Because of brutal suppression during the Qing dynasty thousands of Hui in northwestern and southwestern China were slaughtered or forced to flee their homes, After the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the Hui became even more scattered as they joined in army and took jobs in other regions. Today the Hui are distributed in most of the counties and cities throughout China. With the exception of the Han Chinese, they are the most widely distributed ethnic group in China. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Although there are places where Hui are relatively concentrated, such as Ningxia, some are southeastern regions and Yunnan, for the most part they are found in small concentrations in cities and towns or villages, in certain areas, streets, or parts villages. Unlike groups such as the Yao, Miao or Zhuang, which occupy entire villages by themselves, there are few completely the Hui villages. Hui have traditionally been distributed on transportation lines or near them in order to keep contact with other Huis. Mosques, Muslim holidays and funerals have been the traditionally gathering places and events. They have regular social intercourse and contact with Hui in other areas and often marry Huis from outside their local community. Their scattered communities and unification provided by mosques has allowed to remain unified while not presenting a threat to other groups.

After the founding of the PRC in 1949, the Communist government established the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Gansu Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture and Hui areas allow the Hui some territories they could completely call their own. Otherwise because of their regional diversity, mostly living among Han Chinese, Hui people share many cultural similarities with the Han Chinese, especially in terms of language and food (except many don’t eat pork).

Hui Trading

The Hui are famous inside and outside China for their skill in business and trading. Hui artisans were famous for their craftsmanship in making incense, medicine, leather and cannons, as well as in mining and smelting of ore. Hui merchants played a positive role in the economic exchanges between the hinterland and border regions and in trade contacts between China and other Asian countries. [Source: China.org]

The Hui are famous inside and outside China for their skill in business and trading. Hui artisans were famous for their craftsmanship in making incense, medicine, leather and cannons, as well as in mining and smelting of ore. Hui merchants played a positive role in the economic exchanges between the hinterland and border regions and in trade contacts between China and other Asian countries. [Source: China.org]

Hui commercial activities go back to ancient times. In the Tang and Song dynasties, Muslim "aboriginal guests" were active on the famous "Silk Road" land route as well as the "Perfume Road" (the Maritime Silk Road)—the sea route between China and the Persian Gulf and Middle East, via the Malay Peninsula. The capital Chang'an, the Hexi Corridor region, and Guangzhou, Yangzhou, Quanzhou, Hangzhou and other cities in southeastern China were the main regions where they were engaged in business and inhabited. They opened "Hui restaurants" and "Persian shops" in these places, trading things like perfume, pearls, jewels, ivory, rhinoceros horn, Chinese silk, medicinal materials, copper wares and ceramics. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

In addition to normal commercial and trade activities, at that time, the Hui also operated a kind of barter between state governments, which Chinese historical books called "presenting tribute to emperor". Under this system, the Arabian merchants transported their cargos to China under the pretense of "presenting tributes to the emperor", and "sold" them to the Chinese imperial government. Under these terms, the cargoes were exempt from commercial taxes, and merchants received higher profits. Commercial activities carried by the ancestors of the Huis and other Muslims accelerated communication and cultural exchanges between China and the West, and enriched China and increased its contacts with the outside world.

In the Yuan dynasty, the commercial activities of the Hui were expanded throughout China. They came to play an important role facilitating trade both within China and between China and other places. Perfume, pearls, jewels, gold and silver decorations, grains and pelts were among the commodities they traded. During the Ming dynasty, the Hui nationality became more settled and entrenched in specific places and their businesses prospered within China. But isolationist tendencies in the late Ming period led to decline in foreign trade and hurt Hui involved in international trade. But at home it was said, "the Huis were proficient in earning profits" and "the Huis were good at recognizing valuables". Their commercial activities concentrated in towns and cities. Traders ranged from wealthy merchants and the rich families, some with connections to the imperial government, to ordinary market traders.

From the late Ming dynasty period through the Qing dynasty, the Hui were heavily involved in the cow and sheep industry, slaughtering industry, tanning industry, horse trading, mountain cargo carrying, and the cloth, tea, sugar, oil, salt, and grain sectors. Occasionally they were they victims of persecution and restrictions in part because of jealousy over their success. By the time the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, the Hui not only were major players in only in large scale trade, they also controlled key niches and supply chains. After the founding of new China, many of the traditional businesses of the Hui were taken over by the government. Since reform and opening era launched during the Deng Xiaoping era, the Hui have re-emerged as major traders and businessmen, to the outside world, the Huis people's talents in business have been given full play; their domestic and foreign business and trade have got all-directional development.

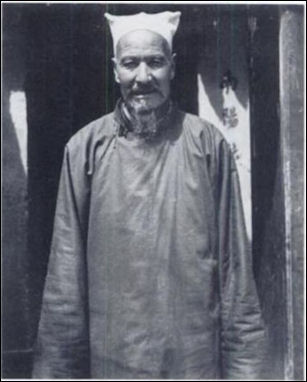

Hui Revolts in the Qing Period

During the mid-nineteenth century, there were several revolts and rebellions involving the Hui, including the Muslim Rebellion in Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai and Ningxia in Northwestern China and Yunnan, and the Miao people Revolt in Hunan and Guizhou. These revolts were eventually put down by the Manchu government. The Dungan people were descendants of the Muslim rebels and fled to the Russian Empire after the rebellion. The "Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, Volume 8" stated that the Dungan and Panthay revolts by the Muslims was set off by racial antagonism and class warfare, rather than religion. According to the New York Times, a Hui uprising in northern and northwest China in the last half of the 19th century was so brutally suppressed, it was reported that out of Shaanxi’s 700,000 Hui, only 60,000 survived [Source: Wikipedia +]

During the mid-nineteenth century, there were several revolts and rebellions involving the Hui, including the Muslim Rebellion in Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai and Ningxia in Northwestern China and Yunnan, and the Miao people Revolt in Hunan and Guizhou. These revolts were eventually put down by the Manchu government. The Dungan people were descendants of the Muslim rebels and fled to the Russian Empire after the rebellion. The "Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, Volume 8" stated that the Dungan and Panthay revolts by the Muslims was set off by racial antagonism and class warfare, rather than religion. According to the New York Times, a Hui uprising in northern and northwest China in the last half of the 19th century was so brutally suppressed, it was reported that out of Shaanxi’s 700,000 Hui, only 60,000 survived [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Dungan Revolt (1862–77) erupted over a pricing dispute over bamboo poles that a Han merchant was selling to a Hui. After the revolt broke out, Turkic Andijanis from the Kokand Khanate under Yaqub Beg invaded Xinjiang and fought both Hui rebels and Qing forces. Beg's Turkic Kokandi Andijani Uzbek forces declared jihad against Dungans under T'o Ming (Tuo Ming a.k.a. Daud Khalifa) during the revolt. Hui rebels battled Turkic Muslims in addition to fighting the Qing. Beg seized Aksu from Hui forces and forced them north of the Tien Shan mountains, massacring the Dungans (Hui). Reportedly in 1862 the number of Hui in China proper numbered 30,000,000. During the revolt, loyalist Hui helped the Qing crush the rebels and reconquer Xinjiang from Beg. Despite a substantial population loss, the military power of Hui increased, because some Hui who had defected to the Qing side were granted high positions in the Imperial Army. One of them, Ma Anliang, became a military warlord in northwest China, and other Generals associated with him grew into the Ma Clique of the Republican era. Beijing's Hui population was unaffected by the Dungan revolt. +

The Panthay Rebellion (1895-96) started when a Muslim from a Han family that had converted to Islam, Du Wenxiu, led some Hui to attempt to drive the Manchu out of China and establish a unified Han and Hui state. Du established himself as a Sultan in Yunnan during this revolt. A British military observer testified that the Muslims did not rebel for religious reasons and that the Chinese were tolerant of different religions and were unlikely to have caused the revolt by interfering with Islam. Loyalist Muslim forces helped Qing crush the rebel Muslims. During the Panthay Rebellion, the Qing dynasty did not massacre Muslims who surrendered. Muslim General Ma Rulong, who surrendered and join the Qing campaign to crush the rebel Muslims, was promoted and became the most powerful military official in the province. +

Islam and the Hui

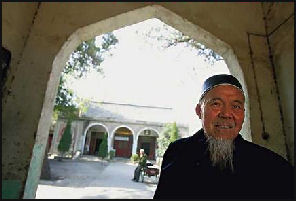

a Sufi Hui

Most Huis are Sunni Muslims in the Hanafi school. Many have never even heard of Shiite Islam. About 20 percent of Huis belong to Sufi orders. They tend to organize themselves in local orders led by Sufi elders. Saint veneration is also common. Schism within orders and conflicts between different orders have occurred. Some Hui mosques have rounded domes like Middle Eastern mosques. Others look more like pagodas. Like other Muslims, the Hui practice ground burials, fast during Ramadan, don’t eat pork and kill cows and sheep using the "halal" ("untainted") method in which butchers cover their head, slit the animals throat and drain the blood. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Ali Osman Ozkan wrote in Fountain magazine, “The mainstream Islam is called gedimu in Chinese, which is the translation of the Arabic word al qadim, "the ancient." They call their Imams ahong, deriving from the Persian word akhong. As seen, it is possible to encounter the translation of both Arabic and Persian terms in the Hui People's religious and daily life expressions. The Hui People also have names in the traditional Chinese forms, along with a religious name. Mahmud Ma Xiao and Sharif Wang Yongliang are examples of Hui names. There are also some common names among the Hui, "like Ma, probably derived from the first syllable of Muhammad" (Dillon, 1996, p.50-53). [Source: Ali Osman Ozkan, Fountain magazine, April 2014 ]

At the time of the Communist takeover of China in 1949, Hui Islam was divided into 40 or 50 branches, with the Zhehelinye, Gadelinye, Hufuye and Kubulinye being strongest. Known as "four greatest official schools", each school had its own history and characteristics. Most were associated with a Sufi saint or deceased charismatic leader. After the founding of modern China, tried to abolish these branches and to some degree was successful. ~

Religious Life of the Hui

In China, Islam has been known as “the Hui religion." The concept of purity is important to the Hui. Restaurants, food products, bakeries and incense packages often have labels that say Islamic ideals of purity are upheld. In most cases this simply means that no pork products are present and the halal method is used. It is even possible to buy Islamic pure instant noodles.

Since 1979, the policies on ethnic minorities and religion have continued in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and elsewhere in the country after disruptions caused by the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). By May 1984, 1,400 mosques had been restored in Ningxia. This has made it possible for Muslims throughout the autonomous region to normalize their religious activities. An institute for the study of Islamic scriptures was established in 1982. It takes in students from among the ahungs every year. An Islamic research society also was set up to conduct academic and research activities on Islam. In recent years, many young Huis have made efforts to learn Islamic classics in Arabic.

Linxia is a small city in Gansu known as China’s Mecca. It is a center of religious life for the Hui. Matthew S. Erie, an expert on Muslims in China, told the New York Times: “The region from Lanzhou to Linxia is often called the Quran belt. When you’re on the highway, it’s impossible to go a minute without seeing a new mosque under construction. “It’s the base of Islam in the northwest. Muslims have built mosques and prayed there since at least the 14th century. Some say certain Muslim tombs there date to the Tang dynasty. That’s hard to prove, but it shows how important it is. It’s a place where Islam took hold.” [Source: Ian Johnson New York Times, September 6, 2016].

Influence of Islam on Hui Culture

Female Hui imam Islam has had a deep influence on the life style of the Hui people. For instance, soon after birth, an infant was to be given a Huihui name by an ahung (imam); wedding ceremonies must be witnessed by ahungs; a deceased person must be cleaned with water, wrapped with white cloth and buried coffinless and promptly in the presence of an ahung who serves as the presider. Men were accustomed to wearing white or black brimless hats, specially during religious services, while women were seen with black, white or green scarves on their head — a habit which also derived from religious practices. The Huis never eat pork nor the blood of any animal or creature that died of itself, and they refuse to take alcohol. These taboos originated in the Koran of the Muslims. The Huis are very particular about sanitation and hygiene. Likewise, before attending religious services, they have to observe either a "minor cleaning," i.e. wash their face, mouth, nose, hands and feet, or a "major cleaning," which requires a thorough bath of the whole body. [Source: China.org]

Islam also had great impact on the political and economic systems of Hui society. "Jiaofang" or "religious community," as once practiced among the Huis, was a religious system as well as an economic system. According to the system, a mosque was to be built at each location inhabited by Huis, ranging from a dozen to several hundred households. An imam was to be invited to preside over the religious affairs of the community as well as to take responsibility over all aspects of the livelihood of its members and to collect religious levies and other taxes from them. A mosque functioned not only as a place for religious activities but also as a rendezvous where the public met to discuss matters of common interest. Religious communities, operating quite independently from each other, had thus become the basic social units for the widely dispersed Hui people.

Conservative Versus Liberal Islam Among the Hui

Compared to other Muslim minorities, namely the Uyghurs, the Hui enjoy much more freedom in terms of practicing Islam. Political issues and worries about terrorism have lead to the Chinese government restricting some Islamic practices of some Muslim minorities. For example, Beijing closely monitors and restricts the political, cultural and religious activities of Uyghurs because they are considered as a threat to national unity.

Hui’s generally have a relaxed view towards Islam and Beijing regards them as less likely to embrace extremism than the Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Many have all but abandoned Islam except for traditions of not eating pork and circumcising male children. The Hui the northeast are generally more liberal than those in the north.

In many places in the north the Hui are very conservative and are becoming increasingly more so. They want their children to get a religious education and don’t see the merit n studying Chinese. In some places smoking and drinking alcohol are banned. Wahhabism is strong in Gansu and Qinghai. Many drink and eat pork. Many Hui are angry about what has happened to Muslims in Iraq. One street vendor told Reuters, “In our hearts we are especially angry. Such a huge and powerful country picking on a small country!”

Hui Festivals, Funerals and Muslim Holidays

The primary Hui festivals are Lesser Bairam (End of Ramadan), Corban, and Shengji Festival. Huis also observe Han Chinese celebrations such a the Spring Festival (Chinese New Year) and the Mid-Autumn Festival of China. Many Hui observe Ramadan. During the entire ninth month of to the Islamic calendar, men older than 12 and women older than 9 are expected to fast from sunrise to sunset. The celebration Lesser Bairam begins on the first day of the tenth month and lasts three days. Relatives and friends eat choice cuts beef and mutton and special fired cakes. The Shenji Festival on the 12th day of third month of the Islamic calendar) is a memorial to Muhammad. The Hui will go to the mosque to greet each other and to participate in religious activities. Food and drink are offered at mosques for the Muslims.

"Lesser Bairam" is name used to describe the festival known in much of the Muslim world as Eid-al-Fitr. On the last day of Ramadan, the new moon (crescent moon) can be seen, and the fasting comes to an end, the next day is Lesser Bairam. Muslim begin the day with a "big cleaning". They thoroughly clean themselves and put on their best clothes and go to their local mosque for a sermon led by an imam or ahung. People greet one another with the words "seliangmu" (meanings "I wish Allah would grant peace and happiness to you"). According to Islamic beliefs, all Muslim must donate "festival kesan" (a kind of donation) or place money in the "mietie box" (donation box) in their mosques, or help the poor in some other way. Participants call on relatives and visit friends, gather in groups for feasts, have a good tim and engage in various kinds of festival activities. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Corban Festival—also known as Edi Al-Adha Day, or the Feast of Sacrifice— is celebrated on the tenth day of the twelfth month according to the Islamic calendar. Every year on this day, animals such as camels, oxen and sheep are killed to mark Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son to Allah. The morning of this festival, Hui do not eat breakfast. After visiting their local mosque, they kill an oxen and then share the meat with poor families and relatives. The selling of oxen is not permitted on this day. Hua'er is a form of folk singing among Hui people, especially prevalent in Ningxia, Gansu and Qinghai. During festivals and the sixth month of the lunar year, there is a pageant and people sing joyfully for six days. [Source: travelchinaguide.com, chinatravel.com]

Funerals are simple, but there are many taboos which must be avoided. For example, mourners are not supposed to wail, as that is considered disrespectful to the dead. The Hui refer to death as "wuchang" or "returning to original purity" and require the the body be buried quickly in the ground. They advocate a thrifty burial, with no funerary objects, and forbid using inner and outer coffins. After death, the corpse is cleaned by plain water, dressed in a "kefan" (white cloth to bind and wrap the corpse). An ahung is invited to "zhenazi" (chair the funeral). After the corpse is placed into the tomb, it should face west, towards Mecca. ~

See Muslim Holidays: factsanddetails.com factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, Nolls, Mongabey

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022