MUSTELIDS (MUSTELIDAE)

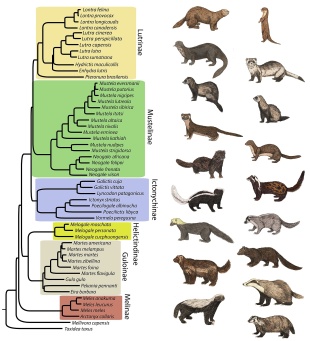

Mustelidae are a diverse family of carnivoran mammals, including weasels, badgers, otters, stoats, mink, sables, ermine, fishers, ferrets, polecats, martens, grisons, wolverines, hog badgers, honey badgers and ferret badgers. Also known as mustelids, they make up the largest family within Carnivora with about 66 to 70 species in eight or nine subfamilies and 22 genera. Skunks were considered a subfamily within Mustelidae, but recent molecular evidence has led their removal from the mustelid group. They are now recognized as a their own single family, Mephitidae. [Source: Wikipedia, Matt Wund, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Mustelids have razor-sharp teeth, and most are primarily carnivorous. Some of the smaller species, however, are quite omnivorous, and supplement their diet heavily with fruits and berries. A characteristic of the family is powerful anal scent glands that are used to mark territory and as a form of communication among individuals in a breeding population. The most formidable members of the family are the wolverines, which hold their own in fights against lynxes, wolves and even bears. Mink, sable and ermine are valued for their luxurious fur. The cutest and most popular members are usually the intelligent, sociable otters. Ferrets are kept as pets.

Mustelids inhabit all continents except Australia and Antarctica, and do not live on Madagascar or oceanic islands. They are found in diverse terrestrial and aquatic habitats in temperate, tropical and polar environments — in tundra, taiga (boreal forest), conifer forests, temperate forests, deserts, dune areas, savanna, grasslands, steppe, chaparral forests, tropical and temperate rainforests, scrub forests, mountains, lakes, ponds, rivers, streams. coastal brackish water, wetlands such as marshes, swamps and bogs, suburban areas, farms, orchard and areas near rivers, estuaries and intertidal (littoral) zones.

Mustelids vary greatly in behaviour. They are mainly carnivorous and exploit a wide diversity of both vertebrate and invertebrate prey, with different members specializing in certain kinds of prey. Most mustelids are adept hunters with some weasels able take prey much larger than themselves. Many species hunt in burrows and crevices; some species have evolved to become adept at climbing trees (such as marten) or swimming (such as otters and mink) in search of prey. Wolverines can crush bones as thick as the femur of a moose to get at the marrow, and have been seen attempting to drive bears away from their kills. Mustelids typically live between five and 20 years in the wild. |=|

Mustelids vary greatly in size and morphology. Generally, they have elongated bodies with short legs and a short rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth), as typified by weasels, ferrets, mink, and otters. Wolverines and badgers have broader bodies. The smallest species is the least weasel (Mustela nivalis), weighing between 35 and 250 grams and measuring under 20 centimeters (8 inches) in length. The largest are the giant otter of Amazonian South America which can reach up to 1.7 meters (5.6 feet) and sea otters that can weigh more than 45 kilograms (99 pounds). All mustelids have well developed anal scent glands, which serve various functions, including territorial marking and defense. |=|

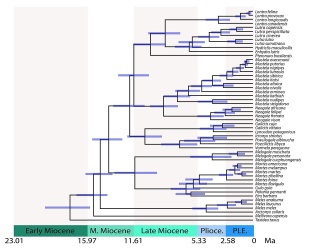

The earliest mustelid fossils are from the Old World and have been dated to the Oligocene Period (33 million to 23.9 million years ago) (33.5 — 23.8 million years ago) or mid-Miocene (23.8 — 5.3 million years ago). There is debate regarding which fossils from these epochs represent possible ancestral forms that led to Mustelidae and which fossils represent the first modern mustelids. |=|

RELATED ARTICLES:

BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BADGER SPECIES factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FOLKLORE factsanddetails.com

WOLVERINES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

HOG BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

FERRET-BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

STINK BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

Mustelid Characteristics and Diet

Mustelids generally have long, slender bodies with short legs. Some, like badgers and wolverines have much broader bodies. The skull is elongated with a relatively short rostrum (hard, beak-like structures projecting out from the head or mouth). The ears are short. Each foot has five digits. The claws do not retract and, being digging species, are especially robust. Mustelids are digitigrade (walking on their toes and not touching the ground with their heels, like a dog, cat, or rodent) or plantigrade (walking on the soles of the feet, like a human or a bear). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Adult males are generally about 25 percent larger than females of the same species. [Source: Wikipedia, Matt Wund, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

According to Animal Diversity Web: The dental formula varies among species: 3/3, 1/1, 2-4/2-4, 1/1-2 = 28-38. The canines are long, and the carnassials are well-developed. The upper molars are often narrow in the middle, giving them an hourglass shape. Mustelids have a powerful bite; in many species, the large postglenoid process locks the lower jaw into the upper, causing the lower jaw to only move in the vertical plane, without any rotary motion.

Mustelids are primarily carnivorous, but some species may eat plant material from time to time. A wide range of animals are preyed upon. On one hand many mustelids are opportunistic feeders rather than specialists. But on the other hand many mustelids are especially adept at capturing small, mammalian prey. Weasels are very good at chasing and capturing rodents in their burrows. Otters are well-adapted for catching fish and aquatic prey. Some species regularly prey on animals larger than themselves. Others store and cache food

The metabolism of mustelids is very high. Food can travel through their digestive tract in as little as three to five hours. They are very active and need to eat a lot and often. It has been shown that in some mustelid species hunting is innate. Some that have been raised in captivity have been able to hunt and kill without any training when released in the wild. Domestic ferrets possess olfactory imprinting. What ever is fed to them for the first six months of their life is what they will recognize as food in the future. [Source: Jessica Duda, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Mustelid Behavior

Depending of the species, mustelids are scansorial (able to or good at climbing), terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), natatorial (equipped for swimming), diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), territorial (defend an area within the home range).[Source: Wikipedia, Matt Wund, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Mustelids generally are either mostly diurnal or mostly nocturnal. Many are quick and agile, and move in a bounding, scampering fashion. The broader-bodied forms have a more lumbering gait. Some species are adept climbers, while others are excellent swimmers. Many species spend a great deal of time on the ground, searching for food in crevices, burrows, or under cover. Many species shelter in burrows.

Some species are social, while others are solitary. Social organization can vary both within and among species, and may vary in relation to local environmental conditions such as food availability. For example, European badgers are known to form groups with several males and females that are all reproductively active within the group. Yet in other parts of their range, European badgers may live solitarily or in pairs. Many species are territorial, for at least part of the year, with individuals competing over hunting areas or access to mates (such as Mustela erminea).|=|

Mustelids sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also leave scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. Vision and hearing are important, but olfaction (smelling( is particularly well developed. Smell is used to find food and scent-marking is the main form of communication. Secretions from well-developed scent glands define territory, indicate reproductive state, and used in other social contexts. The degree and function of scent marking varies among species, and according to social and environmental conditions within species. |=|

Mustelid Mating. Reproduction and Offspring

Mustelids generally polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). Mustelids require prolonged periods of copulation to induce ovulation of an unfertilzed egg. As a result, copulation may last for several hours before fertilization can be successful. Most mustelids breed seasonally, but the length of the reproductive period varies among species. Day length often dictates the onset of the breeding season, which usually lasts three to four months. [Source: Wikipedia, Matt Wund, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Many mustelids undergo delayed implantation (a condition in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the uterine lining, sometimes for several months), with the fertilized embryo taking up to 10 months to implant in the uterus in some species. Environmental conditions such as temperature and day length determine when implantation occurs. Mustelids that live in more seasonal climates are more likely to exhibit delayed implantation.

Following implantation, gestation typically lasts 30 to 65 days. Females give birth to a single litter each season, the size of which varies within and among species. For example, sables have an average litter size of 2.2, but can give birth to anywhere from one to seven pups. The mountain weasel averages 8.7 pups per litter, but can have between three and 14 young in a single bout of reproduction.

Some mustelids have a hooked penis. After penetration of the female, they can’t be separated until the male releases. Males may also bite the back of the female’s neck while mating. Domestic ferrets have a seasonal polyestrous cycle. Female in estrus are identifiable by a swollen pink vulva due to an increase in estrogen. Females can go into lactational estrus on some occasions. Lactational estrus occurs if the litter size is less than five kits. Lactational estrus is when the female will go back into estrus while lactating the litter that she just had. [Source: Jessica Duda, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Generally, mustelids are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. There are born blind and are very small at birth. Parental care is generally done by females. Young requiring extensive care and protection from their mother, especially after they are born. Young need at least eight weeks of parental care. Baby incisors appear about 10 days after birth. Eyes and ears open when they are a few weeks old. After a couple of months young have permanent canine teeth and are capable of eating hard food. Young mustelids typically are able to care for themselves when they are about two months old. Females defend territories in order to acquire enough resources to care for their young and most often nurse and protect them in a burrow or den. Young reach sexual maturity between eight months and two years following birth. |=|

Mustelids, Humans and Conservation

Many mustelids help humans by controlling rodent populations that are considered to be pests. Also, many are hunted and/or raised for their pelts. Those of mink and sable are are highly valued. Some species such as ferrets have been at least partyly domesticated and are kept as pets. [Source: Wikipedia, Matt Wund, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Some mustelids are considered pests because they harm or kill poultry or livestock, threaten other species in the wild, or for transmitting diseases. European badgers are responsible for the transmission of bovine tuberculosis. Cattle may become infected from grazing on land where badgers have defecated. Up to 20 percent of badgers carry the disease in areas where bovine tuberculosis is a problem. Since 1975, badgers have been culled in the United Kingdom, but there is no conclusive evidence that it has helped control bovine TB. As mammalian carnivores, mustelids can also be infected by, and transmit, rabies.|=|

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List most mustelids are listed as species of least concern or are not evaluated But some are considered endangered or threatened. Approximately 38 percent of all species of Mustelidae are considered threatened, which is a much higher proportion than mammals in general (15 percent). Habitat destruction and overhunting are the main cause. Smaller carnivores that are restricted to small habitat fragments may also be at risk to predation by larger carnivores that can more easily move among fragments. . Endangered mustelids include: Colombian weasels (Mustela felipei), European mink (Mustela lutreola), Indonesian mountain weasels (Mustela lutreolina), marine otters (Lontra felina), southern river otters (Lontra provocax), and giant Brazilian otters (Pteronura brasiliensis). Sea mink (Neovison macrodon) became extinct in relatively recent times. |=|

Numerous re-introduction programs for various mustelid species have met with mixed success. Generally, "soft" re-introductions, those that allow the animals to acclimate to their new surroundings while in a temporary enclosure, are more successful than "hard" re-introductions, in which captive-bred animals are released directly into the wild. Black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes) are considered near extinct in the wild. Several re-introduction programs are taking place for them. |=|

Weasels, Ermine, Minks and Sables

Weasels, minks and sables are all very similar and have similar characteristics and behavior. Minks and sables live primarily in northern regions of North America, Asia and Europe and produce highly-prized fur used in coats and stoles. Weasels are found in more southern areas and have shorter fur. Nowadays furs are out of fashion in North America and Europe but are still popular in Russia and have become popular in China.

Ermine — also called stoats, short-tailed weasels, or Bonaparte weasels — are a northern weasel species that turn white in the winter. Widely distributed across northern North America and Eurasia, ermines are most abundant in thickets, woodlands, and semi-timbered areas. These slender, agile, voracious mammals measure 13 to 29 centimeters (5 to 12 inches) in head and body length. The term “ermine” also describes the animal’s pelt was used historically in royal robes and crowns in Europe. [Source: Encyclopedia Britannica]

Weasels, minks and sables are closely related to ferrets, martens and polecats. They all have similar body shapes and are belong to the mustels. There are much fewer sables and minks than fox, which are all prized in the fur industry. These days minks are raised on farms. In the old days they were caught by trappers. Because they don’t breed well in captivity sables are still largely caught by trappers and hunters.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MARTENS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

MINKS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, INVASIVE AND ENDANGERED SPECIES factsanddetails.com

MINK FUR: QUALITY, FARMS AND ANIMAL RIGHTS factsanddetails.com

SABLES: CHARACTERISTICS, FUR, BEHAVIOR, TRAPPING, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

ERMINE (STOATS): CHARACTERISTICS, FUR, BEHAVIOR, ROYALTY, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

FURS; RUSSIA, HISTORY, FARMS factsanddetails.com

Weasels

Weasels belong to the Order Carnivora and the Family Mustelidae. Although they are small in size they are fearless predators that will eat just about any small animal they can catch. They are mostly nocturnal but are sometimes seen in the day. [Source: Richard Conniff, Smithsonian]

There are ten weasel species. The most well known ones are the short-tailed weasel (also known as ermine or stoat), the least weasel (indigenous to Europe and Asia and introduced to North America and New Zealand), the long-tailed weasel (found mostly in North America). Stoats are similar to weasels. are common the British Isles.

Weasels rarely live more than a year. They are small, long and slender. They range in length from 13 centimeters to 30 centimeters (5 inches to 12 inches) and usually weigh less than half a kilograms (12 ounces). They have short legs, broad flat heads, long necks and powerful jaw muscles and long, sharp canine teeth. Males are generally 25 to 35 centimeters in length not including the tail and weigh up half a kilogram. Females are usually less than half this size.

Like their relative the skunk, weasels posses an anal gland that can spray a nasty smelling liquid that is not as bad as that of skunk but still pretty bad. The spray is used primally as a last measure of defense.

RELATED ARTICLES:

WEASELS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

WEASEL SPECIES OF ASIA AND EUROPE factsanddetails.com

LEAST WEASELS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

POLECATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Sables

The Siberian sable marten is the source of expensive and sumptuous sable fur. They are found almost exclusively in Siberia. Other kinds of sables or martens include the American marten, Chinese sable, American sable, baum marten, Japanese marten and stone marten. Sables are members of the mustelid (or weasel) family.

Sables don't breed well in captivity although some are raised on farms and ranches but of their farm-raised sable is regarded as low quality. They are generally hunted or trapped. and their pelts often sell for more that $1000 a piece. The most valuable fabric in the Renaissance was Russian sable. Worth more than Persian silk, Indian calico, French-worked damask, it was sold mostly from warehouses in Arkhangelsk, northern Russia. Czar crowns were trimmed with sable.

See Separate Article: SABLES factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025