WOLVERINES

Wolverines (Gulo gulo) are the largest terrestrial members of the weasel family (sea otters are larger but are regarded as sea animals). Resembling a cross between a bear and badger, they can weigh up to 20 kilograms (45 pounds) and are found primarily in the boreal forests of Russia, Scandinavia, Canada and Alaska. In the past wolverines have been called skunk bear, Indian devil and carcajou. [Source: Tom O'Neil, National Geographic, June, 2002]

Arik Gabbai wrote in Smithsonian magazine:“No creature of the Far North is less beloved than the wolverine. It has none of the polar bear’s soulfulness, or the snowy owl’s spooky majesty, or even the dewy white fairy-tale mischievousness of the Arctic fox. The wolverine is best known for unpleasantness. This dog-size weasel, which grows to about 30 pounds, has daggerlike claws and jaws strong enough to tear apart a frozen moose carcass. It will eat anything, including teeth. (Its scientific name is Wolverines, from the Latin for “glutton.”) In some cultures it’s known as a “skunk bear,” for the odious anal secretion it uses to mark its territory. And yet, from certain angles, with its snowshoe paws and a face like a bear cub’s, it can appear cuddly. It is not. A wolverine will attack an animal ten times its size, chasing a moose or caribou for miles before bringing it down. “They’re just a vicious piece of muscle,” says Qaiyaan Harcharek, an Inupiat hunter in Utqiagvik, on Alaska’s Arctic coast. “Even the bears don’t mess with them little guys.” [Source: Arik Gabbai, Smithsonian magazine, March 2020]

Because wolverines live in remote areas and are very shy and elusive, relatively little is known about them and few people have seen one in the wild. Wolverines have thick reddish brown fur which keeps them warm in the winter. They have keen senses of smell which helps them find prey and avoid predators. They often rear back on their hind legs to sniff the air for clues about what animals are in the vicinity. Wolverines have skillet-size paws with curved claws that ideal for both digging and climbing trees. Their paws splay out to nearly twice their size and allow them to move quickly on the surface of snow as if they were wearing snowshoes,

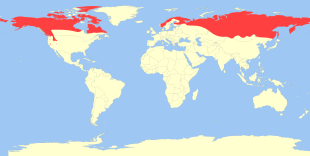

Wolverines were once found as far south as the Black Sea but are now largely relegated to northern areas far from human development. Wolverines are sometimes killed by the dogs, bear, moose and wolf and sable hunters. Wolverine number are unknown. They are sensitive, vulnerable creatures with a low birthrate. The most stable populations are in Russia, western Canada and Alaska.

There are two subspecies of wolverines: 1) North American wolverines (G. gulo luscus) and European wolverines (G. gulo gulo). Differences seem to be mainly genetic and probably as a result of the isolation of these two continental populations. Another possible subspecies lives on Vancouver Island, Canada — g. gulo vancouverensis. This population has skull morphology differences with those found on the mainland, but their status has yet to be decided. |=|

RELATED ARTICLES:

BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BADGER SPECIES factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FOLKLORE factsanddetails.com

MUSTELIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, TYPES, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

HOG BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

FERRET-BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

STINK BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

Wolverine Habitat and Range

Wolverines are found in the boreal zone of northern Eurasia and North America. The boreal zone, also known as the taiga, is a vast, circumpolar region of coniferous forests that stretches across the Northern Hemisphere. It's characterized by long, cold winters and short, cool summers, with many trees adapted to the harsh conditions, such as pine, spruce, and fir. The boreal zone is the world's largest land biome and is home to a wide array of wildlife.

Wolverines are found in Scandinavia and Russia to 50 degrees North latitude. In North America they are found in Alaska and northern Canada, but can also be found in mountainous regions along the Pacific Coast as far south as the Sierras of California. Historically, wolverines were found further south in Europe and North America, but these populations were extirpated mainly due to hunting, clearing of forests, and other human activities. Their distribution once extended as far south as Colorado, Indiana, and Pennsylvania in North America. [Source: Liz Ballenger; Matthew Sygo; Vincent Patsy, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Wolverines require large expanses of relatively undisturbed, boreal habitat to thrive. They are found in alpine forests, tundra, open grasslands, and boreal shrub transition zones at or above timberline. Generally they live in areas with low human development. During the winter, females construct nests to store food and hide young. The nests are rough beds of grass or leaves in caves or rock crevices, or in burrows made by other animals, or under a fallen tree. They occasionally construct their nests under the snow. The cold climates that wolverines live in is conducive to preserving meat for later use — something important to wolverines who rely on scavenging and caching large animal prey.

The wolverine is the emblematic animal by the state of Michigan ("The Wolverine State") and the mascot and symbol for the University of Michigan. However, there is no evidence that wolverines historically occurred there. The "Wolverine State" appellation most likely came about that Detroit got its start as fur trading post for trappers of wolverines and other animals. |=|

Mustelids

Wolverines are mustelids (Mustelidae), a diverse family of carnivoran mammals, including weasels, badgers, otters, stoats, mink, sables, ermine, fishers, ferrets, polecats, martens, grisons, wolverines, hog badgers, honey badgers and ferret badgers. Mustelids, make up the largest family within Carnivora with about 66 to 70 species in eight or nine subfamilies and 22 genera. Skunks were considered a subfamily within Mustelidae, but recent molecular evidence has led their removal from the mustelid group. They are now recognized as a their own single family, Mephitidae. [Source: Wikipedia, Matt Wund, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Mustelids inhabit all continents except Australia and Antarctica, and do not live on Madagascar or oceanic islands. They are found in diverse terrestrial and aquatic habitats in temperate, tropical and polar environments — in tundra, taiga (boreal forest), conifer forests, temperate forests, deserts, dune areas, savanna, grasslands, steppe, chaparral forests, tropical and temperate rainforests, scrub forests, mountains, lakes, ponds, rivers, streams. coastal brackish water, wetlands such as marshes, swamps and bogs, suburban areas, farms, orchard and areas near rivers, estuaries and intertidal (littoral) zones.

Mustelids vary greatly in behavior. They are mainly carnivorous and exploit a wide diversity of both vertebrate and invertebrate prey, with different members specializing in certain kinds of prey. Most mustelids are adept hunters with some weasels able take prey much larger than themselves. Many species hunt in burrows and crevices; some species have evolved to become adept at climbing trees (such as martens) or swimming (such as otters and mink) in search of prey. Wolverines can crush bones as thick as the femur of a moose to get at the marrow, and have been seen attempting to drive bears away from their kills. Mustelids typically live between five and 20 years in the wild. |=|

See Separate Article: MUSTELIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, TYPES, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

Wolverine Characteristics

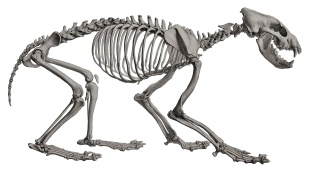

Wolverines range in weight from nine to 30 kilograms (19.8 to 66 pounds) and have a head and body length ranging from 65 to 105 centimeters (25.6 to 41.3 inches). They stand 36 to 45 centimeters at the shoulder (14 to 21.6 inches) . Their tail is 13 to 26 centimeters (5.1 to 10.2 inches) long and their average basal metabolic rate is 31.765 watts. |=| Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females by about 10 percent in length and 30 percent in weight.. [Source: Liz Ballenger; Matthew Sygo; Vincent Patsy, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Wolverines have an unmistakable appearance. They have a stocky appearance, with a robust body, a large head, and small, rounded ears. Their thick reddish brown fur keeps them warm in the winter and skillet-size paws with sharp, curved, semi-retractable claws that are ideal for both digging and climbing trees. Their paws splay out and allow them to move quickly on the surface of snow as if they were wearing snowshoes,

Wolverine fur is usually brown or brownish-black, with a yellow or gold stripe extending from the crown of the head laterally across each shoulder and to the rump, where the stripes join at the tail. They have a very strong bite, powerful enough to crush bone. Unusual upper molars curve inward crush bones and tear frozen meat. Wolverine have the strongest bite with the highest compressive strength all carnivore mammals at 940.8 Newtons, followed by the cheetah at 784.4 Newtons, the Malagasy civet at 714.4 Newtons, the honey badger at 710.8 Newtons and the kinkajou at 693.2 Newtons.

Wolverines have short, powerful limbs and five toes on each paw. They move with a semi-plantigrade form of locomotion, with their weight primarily on their hind limbs. Semi-plantigrade" describes a type of foot posture where the heel does not fully touch the ground while walking, running, or standing. It's an intermediate position between fully plantigrade, where the entire foot and heel contact the ground, and digitigrade, where only the toes support weight. Semi-plantigrade movement distributes weight better and can be useful when traveling and hunting in snow.

Wolverine Food, Hunting and Eating Behavior

Wolverines feed primarily on carrion. They also eat rodents, fish, reptiles and birds. Sometimes they bury meat and eat it later, They seldom attack anything bigger than themselves. Stories about them leaping from trees to kill reindeer and following trappers to their huts are regarded as tall tales. During the winter wolverine often feed on animals that have died in the cold. There powerful jaws enable them to slash through frozen meat and bone. In they decide to hunt, they can outlast most animals in a chase and run as far as 80 kilometers (50 miles) in one go.

Wolverines have been described as “powerful,” “fearless” and “indomitable” hunters. Eric Wagner wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: Like all mustelids, it is carnivorous; it preys on a variety of animals, from small rodents to the occasional snow-bound moose. But primarily it scavenges, at least in winter, digging into the snow to unearth carcasses and biting into frozen meat and bone with its powerful jaws. [Source: Eric Wagner, Smithsonian Magazine, January 2012]

In some places wolverines feed primarily on the carrion left behind from wolf kills. If they stumble across a reindeer or moose carcass they often have to eat fast and take some meat to hide before a bear arrives on the scene. Occasionally wolverines will chase down reindeer. They prefer domesticated one to wild ones because the domesticated are not very good at running in the snow and the wild ones are too skittish, alert and fast. On hard ground, ungulates can outrun wolverines but . In snow, wolverines are less likely to sink in and can often catch much larger animals that become immobilized in deep snow.

Wolverines are primarily carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) and scavengers and mostly eat terrestrial vertebrates or carrion but are also recognized as omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals) as they occasionally eat plant food. [Source: Liz Ballenger; Matthew Sygo; Vincent Patsy, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The wolverine diet can include anything from small eggs to large ungulates. They are capable of bringing down prey that is five times bigger than themselves, but that generally only occurs when ungulate prey are stranded in deep snow. Wolverines have large claws with pads on the feet that allow them to chase down prey in deep snow. Large ungulate prey species include reindeer, roe deer, wild sheep, red deer or red deer, maral and moose. Wolverines can be quick, reaching speeds of over 48 kilometers an hour. Large prey are killed by biting the back or front of the neck, severing neck tendons or crushing the trachea.

Wolverines are opportunistic and their diet vary with season and location. They are also specialized for scavenging and will readily take over carcasses that have been killed by other large predators. They can sniff out carcasses through two meters (6.6 feet) of snow. Wolverines are extremely strong and aggressive for their size, they have been reported to drive bears, cougars, and even packs of wolves from their kills in order to take the carcass. They have also been reported scavenging whale, walrus, and seal carcasses. In Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a wolverine was observed feeding on a caribou killed after being chased over a cliff by wolves. Bears, eagles, foxes and ravens also fed on the carcass for a month.

Female wolverines are better known than males for hunting small to medium-sized animals such as rabbits, hares, ground squirrels, marmots, and lemmings, when they are rearing young. The amount of food available to females may be key in determining population size; more food leads to greater reproductive success. The scientific name Wolverines comes from the latin word for glutton. Like other mustelids, they can be somewhat driven to kill when given the opportunity, resulting in them killing more prey than they can eat or cache. Wolverines have been known to kill large numbers of captive reindeer in deep snow, simply because the reindeer cannot escape. |=|

Wolverines — Omnivorous Reindeer Hunters?

Wolverines are examples of specialist hunters that become omnivores when they can’t get enough of their primary food source. In the “Life of Mammals”, David Attenborough wrote: “The wolverine lives in the Arctic. It is yet another example of an animal that has adapted to cold conditions by growing much bigger than its relations and thus increasing its ability to retain its body heat. Apart from size, however, it still has much the same kind of body as a weasel with sharp dagger-like teeth and short legs. [Source: “Life of Mammals” by David Attenborough]

It hunts reindeer. They with their long legs and under good conditions, can easily outpace the squat, burly wolverine, But they cannot run fast through a deep snow-drifts, They are so big and long-legged that they sink in, often up to their bellies. The wolverine however has feet that are thickly furred and very wide so that its weight is spread over the surface of the snow, like that of a man wearing snowshoes. Consequently it can run over the surface of a snow drift and catch and kill a floundering reindeer, usually by sinking its massive teeth into the base of its victim’s neck.

“Such kills may be rare, so while meat is available the wolverine eats as much as it can. It will consume such phenomenal quantities of flesh at a single sitting that its has been given the alternative name of glutton. It is what you would expect of a giant weasel. Even so, prey is scarce in the Arctic winter and the hunter has to be content with being a scavenger much of the time, eating from carcasses of those animals that have perished in the cold. In summer, conditions are even more difficulty, just as they are for the polar bear. Carrion is not so abundant. And a wolverines stands little chance of catching reindeer for they simply gallop away. So the glutton can no longer be glutinous. It has to look for birds, eggs. It collects berries and roots, It even snatches insects. It has become an omnivore.

Wolverine Lifespan and Predators

In the wild, wolverines generally live for five to seven years but some can live up to 13 years. Females in captivity have bred up to 10 years old and live up to 17 years. The main causes of death are starvation, being killed by competitors (such as wolves), and trapping. |=|

Adult wolverines have few, if any, natural predators. They are fierce and aggressive, able to defend themselves against animals several times their size, such as wolves and mountain lions. However, wolves, mountain lions, black bears, brown bears, and golden eagles can be threats to young or inexperienced wolverines. Wolves are the dominant predator of wolverines, but generally only under circumstances where the wolverine cannot escape by climbing a tree.

Wolverines are well camouflaged in an arboral environment. If the need to flee to safety they can shimmy up a tree. Wolverines are known for their ferocity and have been known to attack black bears and wolves over food. They use scents from their anal gland and urine to scent-mark food caches and discourage other predators from stealing them.. |=|

Wolverine Behavior

Wolverines are terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area) and solitary. The size of the male wolverine’s range territory is huge — 600 to 2000 square kilometers. Female home ranges are 50 to 350 square kilometers. Wolverines may defend smaller territories but its pretty hard to defend the whole thing. Males and females mark the borders of their range with scent from their anal glands. Population densities of wolverines are low because of their requirements for very large home ranges. [Source: Liz Ballenger; Matthew Sygo; Vincent Patsy, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Wolverines don't hibernate. They are very good at climbing trees. They often scale tall pines to survey the landscape for prey, escape from predators and hide food. Wolverines are shy and secretive but they enjoy playing around. They flee when ever they sense people are near. Wolverines usually sleep and seek refuge from wolves, bears and severe storms in rock shelters or under boulders,

In general, wolverines are solitary, only coming together to mate. They generally do not tolerate individuals of the same sex in their territories. They are mostly nocturnal but can be active during the day. In areas where there are extended times of light or darkness, wolverines may alternate three- to four-hour periods of activity and sleep. Wolverines do not appear to be bothered by snow and are active year-round, even in the most severe weather. Wolverines move with a loping gallop. They can climb trees very fast and are excellent swimmers. Wolverines have great endurance, sometimes moving 10 to 15 kilometers without rest. They can average speeds of 15 kilometers per hour for long periods of time and may cover up to 45 kilometers in one day.Play has been observed between mates and between siblings as well as between kits and their mothers. Wolverines are also known to play with objects. |=|

Based on observations of radio-collared wolverines, Arik Gabbai wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “A typical day might include a 12-hour nap in a snow den, followed by 12 hours of nearly ceaseless running to find food, covering as many as 25 miles or more. Several females live within the territory of a single male, which patrols a range of 800 square miles, two-thirds the size of Rhode Island.” [Source: Arik Gabbai, Smithsonian magazine, March 2020]

Wolverines sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. |=| They have keen senses of smell which helps them find prey and avoid predators. They often rear back on their hind legs to sniff the air for clues about what animals and carrion are in the vicinity. Their advanced sense of smell is useful for a scavenging lifestyle. They can sniff out carcasses through two meters (6.6 feet) of snow. Wolverines also have good hearing, but likely have poor vision. Wolverines communicate with sound and chemicals. Like most mustelids, wolverines have anal scent glands which are used to mark territories and food caches. Wolverines are rarely vocal, except for occasional grunts and growls when irritated. |=|

Wolverine Mating and Reproduction

Wolverines are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in delayed implantation (a condition in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the uterine lining, sometimes for several months). Breeding occurs annually from May to August, with females giving birth in alternate years. The gestation period ranges from 120 to 272 days depending on the delayed implantation. The number of offspring ranges from one to five, with the average number of offspring being three. [Source: Liz Ballenger; Matthew Sygo; Vincent Patsy, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Wolverines are generally solitary animals. Males and females come together only briefly for mating. Males have large home ranges, encompassing the home ranges of several females. Males may mate with each female in their home range and sometimes those in overlapping ranges. Males and females remain together for several days. Females may also mate with members of different home ranges, but litters are usually fathered by one male. Males fiercely defend their territory by marking it with scent from their anal gland. |=|

Most females are in heat from June to August. Males remain near females during the breeding season, but females initiate copulation. Like many other mustelids, ovulation is believed to be induced by copulation and the embryo is not implanted immediately, but rather waits in diapause (temporarily suspending its development at the blastocyst stage, delaying implantation in the uterus) for about six months. After implantation, gestation takes only another 30 to 50 days. With delayed implantation pregnancy can last up to 272 days depending on when the embryo is fertilized and when it implants. Females build snow-dens in which they give birth and nurse.

Wolverine Offspring and Parenting

Wolverines young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Parental care is provided by females. The litter is usually born between January and April and averages three kits, weighing 85 grams each. The average weaning age is three months and the average time to independence is one year. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 23.3 months days; males do so at 25.5 months. [Source: Liz Ballenger; Matthew Sygo; Vincent Patsy, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Females usually give birth to a litter of two or three in a snow den. After females give birth they hide with their young. The mother vigorously defends her territory and intruders are not tolerated. This territorial behavior continues until the young are ready to hunt on their own. Young remain with their mother until the fall of the year they were born, when they disperse. Females mate again in the following year, giving birth to young in the second year after the previous litter. Females may help to train their young in hunting techniques before they disperse. |=|

Kits grow fast and spend about eight months with their mother before setting off on their own. The mother takes the kits on hunts and teaches them what she knows. She often favors one kit over the other. Young begin foraging on their own at five to seven months, when they become independent. Adult size is attained at around one year. Wolverines require snow cover that persists through spring so that food can be cached until the kits are large enough to being foraging on their own. |=|

Wolverines often raise their kits in caves dug into snow, with chambers and tunnels leading dozens of feet away from the den. Arik Gabbai wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The birthing dens are tunnel systems of surprising complexity. They might reach ten or so feet deep and extend 200 feet along a snow-buried riverbank, and will include separate tunnels for beds and latrines and others for cached food — caribou femurs, for example. Tom Glass, a field biologist with the Wildlife Conservation Society, told Smithsonian magazine: “We have pictures from reproductive dens of the mother with her kits. They spend a lot of time just playing. They’ll play with each other, and then they’ll go bug mom, who’s taking a nap. It looks like a family scene from any species you can think of. They’re cute and roly-poly.” [Source: Arik Gabbai, Smithsonian magazine, March 2020]

Wolverines, Humans and Conservation

Wolverines rre not endangered. They are fairly uncommon in some places but there are lots of them spread out over a large area in the wilderness of Canada. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status on according to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). [Source: Liz Ballenger; Matthew Sygo; Vincent Patsy, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Wolverine are sometimes hunted for their fur, which is valued for its warmth and frost resistant properties. Native peoples and hunters have traditionally used wolverine fur to line parkas but this is not done so much anymore. Wolverines are said to be very difficult to trap. When a wolverine finds a trap, it may spring it by turning it upside down or by dropping a stick into it. Wolverines have also been known to carry traps away and bury them deep in the snow. |=|

Wolverines live in remote areas where human populations are sparse. They are sometimes killed because they preying upon animals that are trapped for fur. They have been extensively hunted in Scandinavia because their alleged predation on domestic reindeer. They are considered pests in some places because they eat animals already caught in fur traps and break into cabins and food caches, eating and spraying the contents with their strong scent. With their sharp canines, wolverines can even break into canned goods.

Eric Wagner wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: Wolverines have always been mysterious and, to many people, menacing. Such was its gluttony, a Swedish naturalist wrote in 1562, that after coolly dispatching a moose, the wolverine would squeeze itself between closely growing trees to empty its stomach and make room for more food. The popular 19th-century book Riverside Natural History called it an “inveterate thief” that ransacked cabins and stole bait from trap lines set for fur animals. Even as recently as 1979, the wolverine was, to a Colorado newspaper, “something out of a nightmarish fairy tale.” [Source: Eric Wagner, Smithsonian Magazine, January 2012]

Wolverines generally occur at relatively low population densities and have vanished from most of their former range in the contiguous United States. There are a few hundred in each Finland, Norway and Sweden, Encroaching human populations have altered the abundance and habits of large ungulates, which wolverines depend on for food. People have also killed wolverines directly for fur or because they regard wolverines as nuisances. They have also been poisoned by bait meant for wolves. In Russia, wolverines are a game species and extensive overhunting has led to population decline. In the United States, wolverines can only be hunted in Montana and Alaska. Wolverines were once relatively common in the contiguous United States, but trapping and habitat loss have shrunk populations to just 300 or so animals, now mostly confined to the Cascades and Northern Rockies. Arctic populations in Alaska are thought to be healthier. The last stronghold of wolverines is Canada, where an estimated 15,000–19,000 still live. Conservation efforts include education, protecting habitat, and eliminating unregulated hunting. In Sweden farmers and herders are compensated for identifying dens and reporting them. Other Scandinavian countries have adopted measures to limit the amount of wolverines in reindeer herding areas through selected hunting.|=|

Studying Wolverines in Alaska

Arik Gabbai wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Despite temperatures plunging to minus 30 degrees Fahrenheit, winter is prime time to search for elusive wolverines. Tracks and scat are visible. Snow machines cover ground quickly. And bears, always a danger, are hibernating...But the animal’s furtive nature and the vast area each one covers pose a challenge to scientists. “The effort you have to put into finding enough of them to make reasonable conclusions about the population is considerable,” Tom Glass, a field biologist with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), which is conducting a comprehensive field study of Arctic wolverines, told Smithsonian magazine. [Source: Arik Gabbai, Smithsonian magazine, March 2020]

From low-flying airplanes over Alaska’s North Slope, the researchers have observed that wolverines live “pretty much everywhere,” says Martin Robards, of the WCS. Dozens of wolverines trapped on the tundra by researchers and outfitted with satellite collars are revealing how the animals live. Scientists are also testing for diseases and parasites by studying wolverines killed by indigenous hunters, whose subsistence communities prize wolverines for their durable, moisture-wicking fur, a traditional lining for winter parkas.

Glass is particularly interested in how Arctic wolverines use snowpack — for storing food, for shelter from predators and especially for raising their kits, which are born in snow dens in the early spring. Because snow dens appear crucial for ensuring the health of young wolverines, and thus future populations, the research has extra urgency. The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and the snowpack appears to be melting an average of one day earlier every other year.

Matt Kynoch, a Wildlife Conservation Society biologist, inspects wolverine traps. Researchers lure wolverines with meat, sedate them with a “jab stick,” and then attach a satellite collar. When a wolverine takes the bait, a tripwire closes the trap and sends a signal relayed by satellite. The scientists jump on snow machines to reach the animal before it gnaws its way out. A sedated wolverine is weighed before researchers outfit her with a collar It’s attached with a fabric that is supposed to disintegrate in a few months — to minimize impact on the animal. Scientists photograph a sedated animal’s teeth to help determine its health and age. The images can also be used to identify a recaptured wolverine.

Studying Wolverines in Washington State

Eric Wagner wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: Seven biologists and I crunch through the snow in the Cascade Range about 100 miles northeast of Seattle. Puffs of steam shoot from our noses and mouths as we look for a trap just off the snow-buried highway. The trap is a three-foot-tall, six-foot-long box-like structure made of tree trunks and branches. Its lid is rigged to slam shut if an animal tugs on the bait inside. When we find it, the lid is open and the trap unoccupied, but on the ground are four large paw prints. We cluster around them. Keith Aubry glances at the tracks. “Putative,” he says. “At best.” He says they’re probably from a dog...We were hoping they had been made by a wolverine, [Source: Eric Wagner, Smithsonian Magazine, January 2012]

After a jarring snowmobile ride and a slog down a slope of softer, deeper snow, we reach one of the remote camera stations that John Rohrer, of the U.S. Forest Service, has scattered throughout a 2,500-square-mile study area. This one is in a small copse of evergreens. A deer head hangs from a cable and is oddly mesmerizing as it twists in the breeze. Beneath it, a wooden pole juts from a tree trunk. The idea is that a wolverine will be drawn to the fragrant carrion and climb out on the pole. But the bait will be just out of reach, and so the wolverine will jump. A motion-sensitive camera lashed to a nearby tree will photograph the wolverine and, with luck, document the buff markings on its throat and chest, which Aubry uses to identify individuals.

That’s the plan, at any rate. “Mostly we get martens,” Rohrer says of the wolverine’s smaller cousin. To see whether the wolverine really had re-established itself in the Pacific Northwest, Aubry, Rohrer and Fitkin laid three traps in 2006 and baited them with roadkill. “We weren’t expecting much,” Aubry says. “We thought we’d be lucky if we caught even one wolverine.” They caught two: a female, which they named Melanie, and a male, Rocky. Both were fitted with satellite collars and sent on their way. But Melanie’s collar fell off and Rocky’s was collected when he was recaptured a few months later. The second year, the crew collared three wolverines: Chewbacca (or Chewie, so named because he nearly gnawed his way through the trap’s wooden walls before the field crew could get to him), Xena and Melanie (again). The third year, they caught Rocky twice, and the fourth year they caught a new female, Sasha.

Data detailing the animals’ locations trickled in, and by March 2009 Aubry had an idea of the ranges for several wolverines. They were huge: Rocky covered more than 440 square miles, which sounds impressive until compared with Melanie, who covered 560 square miles. Both crossed into Canada. Yet their recorded travels were dwarfed by those of Chewie (730 square miles) and Xena (760 square miles) — among the largest ranges of wolverines reported in North America. More important, though, was that Aubry suspected Rocky and Melanie might be mates, and perhaps Chewie and Xena, too, given how closely their ranges overlapped. A mated pair could indicate a more stable — and potentially increasing — population.

Working with colleagues in the United States, Canada, Finland, Norway and Sweden, Aubry confirmed that the key to wolverine territory was snow — more precisely, snow cover that lasted into May. Every single reproductive den in North America, as well as about 90 percent of all wolverine activity in general, was in sites with long-lasting snow cover. Scientists working in the Rocky Mountains then found that snow cover even explained the genetic relationships among wolverine populations. Wolverines interbreed along routes that go through long-lasting snow.

He points to a string of tracks running along the side of the road. “That 1-2-1 pattern, that’s classic mustelid. And look how big they are.” We gather around. These tracks are the only sign we’ll see of the wolverine, but for Aubry that’s how things usually go. “Most of our contact is like this,” he says. “Very indirect.” Cathy Raley, a Forest Service biologist who collaborates with Aubry, carefully carves one footprint from the snow with a big yellow shovel and holds it out, like a cast. Aubry guesses the tracks are probably two or three days old, judging by their crumbling edges and the light dusting of snow on top of them. It’s worth knowing where the tracks go — maybe to find some hair or scat, something that could be analyzed to determine if they were made by a previously identified animal. So we follow them, looking after them as far as we can, as they wend across the soft relief of the hillside, until they disappear into the broken forest.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025