BADGERS

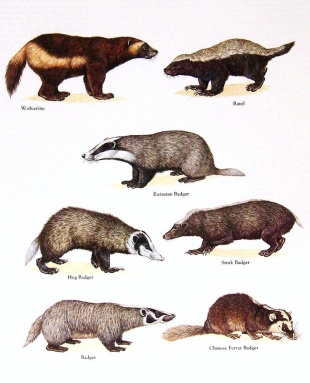

Badgers are medium-sized carnivorous that are so named because early inhabitants of Britain were reminded of badges or heraldry by the animals white facial markings. They are a member of the weasel family along with wolverines, minks, martens and skunks. There are six species of badger found in Eurasia, Africa and North America. They are believed to have evolved from a martenlike creature that originated in Southeast Asia 40 million years ago. European badgers have a longer snout and are more social than their American counterparts, which generally avoid each except during the midsummer when males seek out mates.[Source: Bil Gilbert, Smithsonian]

A male badger is a boar, a female is a sow, and a young badger is a cub. A collective name suggested for a group of badgers is a cete, but badger colonies are more often called clans. A badger's home is called a sett.

Badgers have lived to be 26 years old in captivity. The average lifespan in the wild has been estimated by different researchers at four to five years and at nine to 10 years. The oldest wild badger lived to 14 years. Yearly mortality was estimated at 35 percent by one study. Some populations are estimated to be up to 80 percent yearlings or young of the year, suggesting high mortality rates. [Source: Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Apart from humans, adult badgers generally do not have natural predators. Their geographical ranges overlaps with wolves, lynxes, and bears and these predators sometimes get into conflicts with badgers but adult badgers can usually hold their own against them. These predators as well as large birds of prey occasionally prey on younger badgers. Badgers avoid trouble by hiding in their burrows and put a good fight when cornered or threatened.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BADGER SPECIES factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FOLKLORE factsanddetails.com

MUSTELIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, TYPES, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

WOLVERINES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

HOG BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

FERRET-BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

STINK BADGERS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

Badger Characteristics

Badgers are stout, muscular and have sharp teeth and claws and have been described as one the strongest mammals, pound for pound. Over their muscular bodies is thick fur and loose skin. This makes them hard to kill. Badgers move with a distinctive ambling, bowlegged gait with their front legs turned inward. They can't climb trees but they can swim and run fast if need be.

Badgers have jaws that are hinged in such a way that when they grip something it is difficult for them to let go. Badgers are excellent diggers. The have a transparent inner eyelid, like some bird species, that allows them to see while they dig. Their webbed forepaws and large claws allow them to scoop up dirt as if their legs were shovels.

European badgers have a stocky body with short robust limbs and a short tail. They range in weight from 6.6 to 16.7 kilograms (14.5 to 36.8 pounds), with their average weight being 11.7 kilograms (25.7 pounds). They have a head and body length ranging from 56 to 90 centimeters (22 to 35.4 inches). Their tail is 11.5 to 20.2 centimeters (4.5 to 8 inches) long. Their average basal metabolic rate is 16.647 watts. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Females range in weight from 6.6 to 13.9 kilograms (14.5 to 30.6 pounds), and males range in weight from 9.1 to 16.7 kilograms (20 to 36.8 pounds). Males and females have roughly the same head-body length. [Source: Annie Wang, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

American badgers are stocky and have a flattened body and short legs. The fur on their back and flanks ranges from grayish to reddish. Their belly area is a buffy color. Their face is very distinct. The throat and chin are whitish, and the face has black patches. A white dorsal stripe extends back over the head from the nose. In northern populations, this stripe ends near the shoulders. In southern populations, however, it continues over the back to the rump.

Mustelids

Badgers are mustelids (Mustelidae), a diverse family of carnivoran mammals, including weasels, badgers, otters, stoats, mink, sables, ermine, fishers, ferrets, polecats, martens, grisons, wolverines, hog badgers, honey badgers and ferret badgers. Mustelids, make up the largest family within Carnivora with about 66 to 70 species in eight or nine subfamilies and 22 genera. Skunks were considered a subfamily within Mustelidae, but recent molecular evidence has led their removal from the mustelid group. They are now recognized as a their own single family, Mephitidae. [Source: Wikipedia, Matt Wund, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

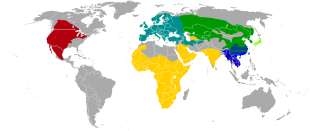

Mustelids inhabit all continents except Australia and Antarctica, and do not live on Madagascar or oceanic islands. They are found in diverse terrestrial and aquatic habitats in temperate, tropical and polar environments — in tundra, taiga (boreal forest), conifer forests, temperate forests, deserts, dune areas, savanna, grasslands, steppe, chaparral forests, tropical and temperate rainforests, scrub forests, mountains, lakes, ponds, rivers, streams. coastal brackish water, wetlands such as marshes, swamps and bogs, suburban areas, farms, orchard and areas near rivers, estuaries and intertidal (littoral) zones.

Mustelids vary greatly in behavior. They are mainly carnivorous and exploit a wide diversity of both vertebrate and invertebrate prey, with different members specializing in certain kinds of prey. Most mustelids are adept hunters with some weasels able take prey much larger than themselves. Many species hunt in burrows and crevices; some species have evolved to become adept at climbing trees (such as martens) or swimming (such as otters and mink) in search of prey. Wolverines can crush bones as thick as the femur of a moose to get at the marrow, and have been seen attempting to drive bears away from their kills. Mustelids typically live between five and 20 years in the wild. |=|

See Separate Article: MUSTELIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, TYPES, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

Badger Diet and Feeding Behavior

Badgers can either be mainly omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals) or primarily carnivores (eat meat or animal parts). They spend their days mostly in their burrows and mainly feed at night. Carnivores mostly eat terrestrial vertebrates. Their diet includes mammals, amphibians, reptiles, birds, insects and non-insect arthropods such as spiders. They may store and cache food. [Source: Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Omnivorous ones often seem to have a special fondness for earthworms. They also eat nuts, fruits, insects, honey, leaves, acorns, other items from the forest and meat. Protein sources for ones in the U.K. include mice, hares, frogs, fish, ground-nesting birds, bird eggs, moles, shrews, fox cubs, rats, ground squirrels, cats, chicken, anything the can lay their claws on. They usually eat fresh meat, but have been observed eating carrion. They also consume large quantities of insects, including wasps, ants, bee larvae, beetles, and grasshoppers. To stay healthy , badgers haveto consume the equivalent of a squirrel a day.

American badgers are mostly carnivorous. Nancy Shefferly wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Their dominant prey are pocket gophers (Geomyidae), ground squirrels (Spermophilus), moles (Talpidae), marmots (Marmota), prairie dogs (Cynomys), woodrats (Neotoma), kangaroo rats (Dipodomys), deer mice (Peromyscus), and voles (Microtus). They also prey on ground nesting birds, such as bank swallows (Riparia riparia and burrowing owls Athene cunicularia), lizards, amphibians, carrion, fish, hibernating skunks (Mephitis and Spilogale), insects, including bees and honeycomb, and some plant foods, such as corn (Zea) and sunflower seeds (Helianthus). Unlike many carnivores that stalk their prey in open country, badgers catch most of their food by digging. They can tunnel after ground dwelling rodents with amazing speed.

American Badgers and coyotes are sometimes seen hunting at the same time in an apparently cooperative manner. Badgers can readily dig rodents out of burrows but cannot run them down readily. Coyotes, on the other hand, can readily run rodents down while above ground, but cannot effectively dig them out of burrows. When badgers and coyotes hunt in the same area at the same time, they may increase the number of rodents available to the other. Coyotes take advantage of rodents attempting to escape from badgers attacking their burrows and it has been demonstrated that coyotes benefit from the association. Badgers may be able to take advantage of rodents that are escaping coyotes by fleeing into burrows, but it is more difficult to assess whether badgers actually do benefit from this association. Badgers and coyotes tolerate each other's presence and may even engage in play behavior.

Badger Behavior

Badgers are terricolous (live on the ground), fossorial (engaged in a burrowing life-style or behavior, and good at digging or burrowing), diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), hibernation (the state that some animals enter during winter in which normal physiological processes are significantly reduced, thus lowering the animal’s energy requirements) and solitary. Typical population density is about five animals per square kilometer. Male American badgers occupy larger home ranges than females (2.4 versus 1.6 square kilometers) but they are not known to defend an exclusive territory. [Source: Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Badgers are mostly nocturnal. They are generally slow moving. Some are solitary. Others are more social, building interlocking systems of dens. European badger often live together in communities with animals of both sexes and different ages that are made of burrows connected to one another by tunnels. Badgers mark their territories with extremely smelly droppings. European badgers hunt individually but gather together to collectively protect their territory. They enjoy grooming and playing with one another.

Badgers don't hibernate. They will sometimes plug their holes and sleep through a couple of days of bad weather but eventually they emerge. During the winter they survive by digging up animals that are really hibernating. American badgers tend to be inactive during the winter months. They spend much of the winter in cycles of torpor that usually last about 29 hours. During torpor body temperatures fall to about nine degrees Celsius and the heart beats at about half the normal rate. They emerge from their dens on warm days in the winter. |=|

Badger Digging and Setts (Dens)

Badgers are excellent diggers. Their powerfully built forelimbs allow them to tunnel rapidly through the soil, and through other harder substances as well. There are stories about them emerging from holes they have excavated through road pavement and two-inch thick concrete. [Source: Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Badgers make their dens in holes that are about the size of a large watermelon split open lengthwise. Sets of badger tunnels and burrows have been occupied by different generations of the same family for centuries. One complex of tunnels in the Mendip Hills of Somerset, England has been continually occupied for 60,000 years.

American badger burrows are constructed mainly in the pursuit of prey, but they are also used for sleeping. A typical badger den may be as far a three meters below the surface, contain about 10 meters of tunnels, and have an enlarged chamber for sleeping. Badgers use multiple burrows within their home range, and they may not use the same burrow more than once a month. In the summer months they may dig a new burrow each day. |=|

European badgers construct large, communal burrow systems called setts. Throughout each group territory there are multiple setts. The main sett generally contains many adults and is centrally located in the group's territory. Younger individuals tend to reside in peripheral setts. Badgers often line their setts with dried grass or other plant material, which are primarily used during winter and autumn. Other resting sites include under rocks, in shrubs, in tree hollows, and in man-made structures that may be scattered throughout a group's territory. Non-sett resting sites are used more frequently during spring and summer. European badgers are nocturnal (active at night), with peak activity periods occurring during dusk and dawn. [Source: Annie Wang, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Badger Senses and Communication

Badgers sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They also employ pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them.They have keen senses of smell and hearing but have poor eyesight. Badgers have nerve endings in the foreclaws that may make them especially sensitive to touch in their forepaws, but this has not been investigated.

European badgers communicate in many different ways. They frequently use postures and visual stances to indicate aggressive behavior. Tail flicking and scraping the hind legs are signs of aggression when individuals feel threatened. Raising of the tail and piloerection are signs of sexual excitement. Badgers also communicate with each other through vocalizations, some of which may be difficult to distinguish from others. Growls from both males and females signify aggression and defense when animals feel threatened. Higher pitched wailing noises signify being attacked. Gurgle noises are used either in aggressive attack or sexual pursuit. Cubs exhibit "whickering" or "keckering" while playing or in trouble. Alarm calls for signaling danger to the rest of the group have not been observed. [Source: Annie Wang, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Scent-marking is a key form of communication in European badgers. Communal latrines as well as subcaudal and anal gland secretions are used to mark group territories. In addition, scent from urine may also indicate the estrus condition of females. Allo-marking of members of their own species using secretions from the sub-caudal gland has also been observed. The purpose of allo-marking may be to create a group-specific odor. |=|

Angry, Hissing Badgers

Badgers are ferocious animals that can easily tear part any dog. They are normally quite docile, but fight fiercely when cornered. Dachshunds (German for "badger hound") were bred to catch badgers. Their slender hot-dog shape allows them to go down badger holes. Even so, its hard to imagine a dachshund being a match for a badger. Badgers have been observed killing Dobermans by ripping them to shreds. Bill Gilbert wrote in Smithsonian magazine: "Of the five dogs I know about that have tackled badgers, four were badly lacerated and the fifth...was killed."

When alarmed away from its burrow, a badger will try avoid being seen by lying flat and pulling its legs under its body. If it thinks it has been seen, it will quickly try to dig a burrow, sending dirt flying high in the air. If it is approached before it hides in it will turn to fight, hissing and snarling. When angered badgers inflate their loose skin like a puffer fish so they look larger than they actually are. When they are only moderately angrily they hiss and growl softly.

Describing an angry badger that had been flushed out its den with water from a hose, Gilbert wrote in Smithsonian magazine: "it began to snarl hiss and gnash its teeth. I cannot describe the racket it made, but since then I have heard buffalo bellow, a lion roar and grizzly growl. No other animal I know sound quite so ferocious as an outraged badger."

Few animals will mess with a badger. If it is attacked by a bite to throat or neck, as most carnivores try to kill their victims, a badger can stretch out the skin on its neck and take the bite of its attacker relatively harmlessly in its forequarters. Occasionally eagles, ravens and dogs take badger cubs.

Badger Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Badgers are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. They employ delayed implantation (a condition in which a fertilized egg reaches the uterus but delays its implantation in the uterine lining, sometimes for several months) and engage in seasonal breeding once per year but the season depends on the species. American badgers typically mate in late summer or early autumn, with implantation is delayed until December or as late as February. The average gestation period is six weeks but with delayed implantion females are technically pregnant for seven months. Litters are born in early spring. The number of offspring ranges from one to five, with the average number of offspring being three. [Source: Nancy Shefferly, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Males have larger home ranges that likely overlap with the home ranges of several females. The home ranges of both male and female badgers expands during the breeding season, indicating that males and females travel more extensively to find mates. Badger mating is usually brief and violent. When it is finished the two animals go their separate ways. Males tend to take care of themselves while females tend to forage for themselves and their cubs.

Badger young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. Pre-weaning and pre-independence provisioning and protecting are done by females. Males are not involved in the rearing of offspring. Female badgers prepare a grass-lined den in which to give birth. Young are born blind with a thin coat of fur. Their eyes open at four to six weeks old, and the young are nursed by their mother until they are two to three months old. Females give their young solid food before they are weaned and for a few weeks after they are weaned. Young may emerge from the den as early as five to six weeks old. The age in which young are weaned ranges from two to three months and the age in which they become independent ranges from five to six months.

The period of maternal care can be relatively short — a few weeks of nursing, a brief period when the mother brings food back to the den and a month or so when the young badger cubs forage and hunt with their mother. After that — in as little as three months after they are born— young can be on their own. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 12 months; males do so at 16 months. Females of some species are able to mate when they are four months old, but males do not mate until the autumn of their second year. Most females mate after their first year. |=|

Badgers and Humans

Methods of catching badgers generally involve different ways of trying to flush them from their burrows. These include smoking them out, pulling them out, digging them out, pulling them out with a social pair of tongs, and using trained dogs to pull them out. Badgers have traditionally been hunted by smoking or digging them out of their dens. Special tongs were developed to pull them and dogs such as dachshunds were trained to enter the dens and pull them out.

Badger fur used to sometimes be used to make women's coats and painting and shaving brushes. They are rarely hunted anymore and are considered endangered in many places. In Russia, the consumption of badger meat is still common. Shish kebabs made from badger, along with dog meat and pork, have been sources of trichinosis outbreaks in the Altai region of Russia.. The word badger means to tease or annoy.

Badger-baiting was formerly a popular blood sport in Britain. Describing a badger baiting contest, Charles A. Long wrote in “The Badgers of the World”: "The captive badger is held within the confines of a restricted space and is then subjected to repeated attacks of specially bred dogs, one at a time...To give an advantage to the dog, the badger is handicapped in the first instance by being secured by a chain...Should this prove ineffectual in preventing the dogs getting mauled...the leg, or legs. of the badger may be broken...The lower jaw of the badger may also be shattered...or sawed off." All badger baiting is illegal today, but there are reports that dog-badger fights are still staged.

One of the main charters in Kenneth Grahams's “Wind in the Willows” was Mr. Badger. In one passage, Mole asks Mr. Badger what happened to the original builders of his tunnels. "'Who can tell?' said the Badger. 'People come—they stay for a while, they flourish, they build—and they go. It is their way. But we remain. There were badgers here, I've been told, before that same city ever came to be. And now there are badgers here again. We are an enduring lot, and we move out for a time, but we wait, and are patient, and back we come. And so it will ever be.'"

In the 1990s, there were 80,000 badgers in Great Britain. But their numbers are shrinking. At that a number were dying as a result of cattle tuberculosis they originally got from cattle.

Badgers sometimes help archaeologists. In 201, according to Archaeology magazine: In northern Germany, a badger discovered nine remarkable 900-year-old burials, including that of a richly outfitted warrior. “There was no knowledge of these graves and no reason to investigate without the badger’s assistance,” says archaeologist Felix Biermann, who continues to dig the site. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, January-February 2014]

Dachshunds and Badgers

Dachshunds were originally bred to hunt badgers in Germany. Their long bodies and short legs allowed them to navigate badger burrows, and their fearless temperament made them well-suited for confronting larger prey like badgers. Miniature dachshunds were bred to hunt smaller animals like rabbits. The term "Dachshund" itself translates to "badger hound" in German, highlighting their historical role in badger hunting. Their long bodies and short legs, coupled with their strong paws, enabled them to enter and dig in badger burrows. Dachshunds were bred to be brave and tenacious, making them unafraid to face larger and stronger animals like badgers. Dachshunds would track and follow the scent of a badger, enter its burrow, and then alert their human companions by barking.

In the 18th Century German foresters and hunters began to breed the dogs that becam dachshunds. According to the American Kennel Club: Badgers did not give up their pelts without a fight. With their thick skin and skulls, and sharp teeth and claws, badgers were well prepared to fend off any intruder. Creating a dog for such a highly specific and dangerous job required several rather dramatic modifications of the canine form. The dogs obviously had to have short legs so they could easily fit in the badger holes. Those legs had to be slightly curved around the ribcage. Plus, they needed tight, compact feet to push the soil behind the dog as it dug toward its quarry. A well-angled shoulder and upper arm allowed for the range of motion required for this digging, creating a prominent breastbone and forechest, known as the “prow.”

The list of must-haves – and the nautical imagery – didn’t end there. The dog’s ribcage had to be long and well developed, providing ample room for the heart and lungs to give the dog the endurance it needed to battle for hours underground. The “keel,” or underside of the ribcage, needed to extend well beyond the elbow, protecting the internal organs from any sharp sticks or roots that protruded from the earth.

And since the dog had to face the badger head-on, with no room to turn around, its “business end” was of equal importance: The prominent bridge bone over the eyes offered protection, and a strong, well-hinged underjaw with surprisingly large teeth let the Dachshund give back as good as it got. Trapped in tight tunnels, relying on its own wits, the Dachshund needed to be independent, bold, and not a little bit combative. It’s no wonder the Dachshund standard describes these dogs as “courageous to the point of rashness.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025