KIMAAM

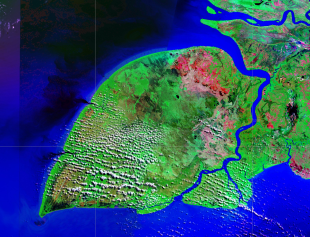

The Kimaam people are an ethnic group inhabiting Yos Sudarso Island (Kimaam) in the western part of Merauke Regency, South Papua Province, Indonesia. Also known as the Kimam, Riantana, Kimaghima or Kimaima), they are considered a sub-group of the Marind people, although they speak languages within the Kolopom language family. “Kimaam” can also refer to the inhabitants of Yos Sudarso Island—a 102-mile-long island in Papua, Indonesia, located between 137.7–139.1°E and 7.4–8.5°S. Covering 11,743 square kilometers (4,534 square miles), it is separated from mainland New Guinea by the narrow Muli Strait. Formerly known as Frederik-Hendrik Island, it was renamed Yos Sudarso Island after Indonesia assumed administration in 1963. Other local names include Kolepom, Kimaam, and Dolak. [Source: J. Patrick Gray, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September, 2019]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Kimaam population in the 2020s was 5,100. The population of Yos Sudarso Island in 2018 was about 11,000. In the early 1960s, it was roughly 7,000, spread across 25–30 villages—about 3.9 people per square kilometers (1.5 people per square mile). The Kimaam population is found mostly in Kimaam, Waan, Tabonji, Padua, and Kontuar districts. Kimaam Island lies in the western part of Merauke Regency and is accessible by boat and airplane, with an airstrip located in the capital of Kimaam District. The island’s topography resembles a shallow saucer: the coastal rim is higher than the marshy interior. During the rainy season (January–May) the central basin floods and then slowly drains during the dry season, though it never fully dries. The interior supports reeds and rushes, while the coasts have wide mangrove belts. Isolated higher areas in the northeast, west, and south contain savanna grasslands and eucalyptus forest.

Language: Three main languages are spoken on the island, all part of the Kolopom branch of the Trans–New Guinea language family. Most Kimaam people speak the Kimaama language (Kimaghama), but some communities in specific regions of the island speak distinct languages. Riantana is restricted to villages around Suam Village in Tabonji District in the northwest, and Ndom to several villages in the southwest around Kalilam Village in Kimaam District. Mombum and Konorau are spoken only in the villages of Wan and Koneraw on the south coast, and on the small offshore island of Komolom. Linguistic differences do not correspond to major distinctions in other cultural domains.

History: According to tradition, the Kimaam migrated from the Digul River region on the mainland to escape headhunting raids. Dutch explorer Jan Carstensz reached the island in 1623, but sustained government and missionary presence began only in the 1930s, centered in the eastern village of Kimaam. Colonial administrators and Catholic missionaries attempted to consolidate settlements and suppress certain traditional practices. By 1960–62, bachelor-hut ceremonies and rituals involving the collection of sperm for headhunting or gardening magic had largely disappeared. Villages were required to seek government permission to perform dances linked to competitive feasting, mortuary rites, yam magic, and bachelor-hut traditions. Before Dutch pacification, inter-village headhunting occurred, though the Kimaam more often suffered raids by mainland Marind-Amin and Digul River groups. Elements of Marind-Amin culture—such as dances and totemic names—occasionally diffused to the Kimaam.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SOUTHERN LOWLANDS OF PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

MARIND PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (SOUTHWEST NEW GUINEA, INDONESIA) factsanddetails.com

Kimaam PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

ASMAT: HISTORY, RELIGION AND HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

ASMAT LIFE: SOCIETY, MARRIAGE, FOOD, VILLAGES, WORK factsanddetails.com

ASMAT CULTURE: MUSIC, FOLKLORE, CEREMONIES, BODY ADORNMENT factsanddetails.com

ASMAT ART: BIS POLES, SPIRIT CANOES, BODY MASKS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI PEOPLE: HISTORY, CANNIBALISM, CONTACT WITH WESTERNERS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI LIFE AND SOCIETY: RELIGION, FOOD AND TREEHOUSES factsanddetails.com

ASMAT AND KOROWAI COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

Kimaam Religion and Views on Death

Many Kimaam are Roman Catholics. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 65 percent of Kamaro are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent. Relatively little is known about traditional Kimaam religion. The culture hero Kuruamma was an exceptionally tall figure who could shed his skin like a snake. According to tradition, human death originated when his wives destroyed his discarded skin. Kuruamma established mortuary rites, competitive feasting, and discovered the underworld (wètewutu), the destination of all humans after death. A second culture hero, Adjeriga, is associated with the origin of taro cultivation and the institution of headhunting. Supernatural beings called aga appear in visions to men seeking to become warrewundu (holders of gardening magic). The vision reveals a location where the initiate can find a tangible manifestation of the spirit, which becomes the source of his magical power. [Source: J. Patrick Gray, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September, 2019]

Religious Practitioners The most important ritual specialists are the warrewundu, who provide garden magic for their followers. Sorcerers (undani) are believed to cause both illness and death as well as to heal; most deaths are attributed to sorcery from members of the opposite village sector. Men renowned for powerful garden magic often have reputations as the strongest sorcerers.

Death is typically attributed to sorcery except in cases involving the very young or very old. Death occurs when the person’s vital essence (rimètje) leaves the body. After death, an immaterial component called the wèwe can bring illness or death to others, and the newly dead are feared for seeking the company of their closest relations.

Funerals: The corpse is removed from the house immediately, and relatives avoid the dwelling throughout the mourning period. Mourners cover themselves in mud and wear hoods for up to eighteen months. Only men from the opposite village sector may conduct the burial. Adults are interred in their canoes on their dwelling islands, with a coconut placed at the feet to capture the departing wèwe. This coconut is later used by a sorcerer to identify the sorcerer responsible for the death.

Following a burial, the village enters a period of restrictions—prohibitions on fishing, loud noises, dancing—lifted gradually during a sequence of mortuary feasts. As the corpse decomposes, another immaterial component conceptualized as heat or vibration spreads from the burial island, causing gardens to “close.” By the time of the final ceremony, the gardens of the entire paburu (village sector) may be under restriction, which ends after the concluding rites.

A third immaterial component, the numba-numba, is envisioned as a white shadow that journeys to the wètewutu, the afterlife located at the bottom of a deep hole in the earth where food is abundant and dancing continues. Once the numba-numba has completed its journey, the men who buried the corpse reopen the grave, clean and oil the bones, and rebury them; afterwards the grave is leveled and left unmarked.

Kimaam Celebrations and Ceremonies

The Kimaam enjoy the Ndambu dance, and wati, an intoxicating drink, which is served up at many social occasions. Most people now wear modern clothing. Ndambu—meaning “healthy competition”—is an annual traditional festival on Kimaam Island. Historically, it served as a way to settle disputes between villages, clans, and districts. Today the festival features agricultural displays, canoe races, traditional archery, wrestling, crab catching, weaving, sago processing, canoe carving, and other competitive events. [Source: Wikipedia, Joshua Project]

Kimaam ceremonial life is organized around three key principles: 1) Yam planting as symbolic rebirth: The planting of yams is equated with burial, and the harvest represents the deceased’s rebirth in yam form. 2) Structured ceremonial rivalry: Social units—especially the two sectors of each village—engage in formalized antagonistic cooperation. 3) Well-being expressed through competitive feasting: A sector’s vitality is demonstrated by its performance in ndambu feasts. [Source: J. Patrick Gray, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September, 2019]

Ndambu feasts serve many purposes, the most significant being their role in mortuary rites between village sectors. By displaying and distributing food to the opposite sector, a group demonstrates its continued strength in the face of death—particularly meaningful when death is attributed to sorcery by the rival sector. Several rituals related to childhood transitions and bachelors’ huts can only be performed alongside mortuary ceremonies, reinforcing this message.

Ndambu may also be held to resolve conflicts such as food theft, adultery, or wife-stealing. Warrewundu (master cultivators) from opposing sectors sometimes challenge each other to enhance their prestige. During these events, ceremonial crops are displayed, and the largest yams and taro are measured and publicly announced. Prestige comes from the size of the crops and the quality of the food and wati distributed. When a ndambu arises from a direct challenge, both sides attempt to match each other’s offerings. Failure to equal the challenger’s contribution results in a loss of status. Most ndambu include competitive dancing as well. Cultural variations exist across the island: In villages located on sandy coasts, sweet potatoes replace yams and taro as the primary ceremonial crops. In Ndom-speaking villages, ceremonial crops are displayed and measured but not given to the opposing group.

Kimaam Family and Marriage

The basic domestic unit of the Kimaam is the nuclear family, each with its own night hut or its own section within a shared house. When several families occupy the same dwelling island, each maintains separate huts, storage areas, and fireplaces, and prepares and eats its meals independently. Entering another family’s hut or storage area without permission is forbidden. Multi-family dwelling islands typically house a father and his married sons, or an elder brother and his siblings. Government efforts to relocate families into single-family houses were resisted; such houses were instead subdivided into two separate living spaces, each with its own door and verandah. [Source: J. Patrick Gray, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September, 2019]

Marriage involved two rituals. A couple was considered married once they shared a porridge prepared by the bride’s relatives using tubers provided by the groom’s family; only their age-mates attended this meal. A second ritual—an exchange of food between the two kin groups—formalized the marriage contract and was attended by elders only. By the 1960s, Catholic wedding ceremonies had become universal, followed immediately by the joint meal, but the ceremonial exchange of food remained essential for validating the marriage.

The preferred form of marriage is sister exchange, often arranged in childhood. If a man lacks a sister, he must offer a classificatory sister. A woman’s elder brother plays a key role in these arrangements. Under government and missionary influence, direct exchange became less common, replaced by bride-price marriages, which were popular partly because they brought European trade goods. Elopements occurred as well, after which the bride’s group demanded compensation. Polygyny is permitted but uncommon, and widowers are expected to marry widows. Second marriages require no compensation. Sororate unions occur only when both parties are widowed; levirate marriages are common in some villages.

Group affiliation weighs more heavily than kinship in determining marriage partners. Marriages are typically exogamous (outside the group) at the ward level but endogamous (inside the group) at the sector level. First-cousin marriage is forbidden, but second- and third-cousin unions are allowed if the partners belong to different wards. While marriages ideally occur within the village, smaller communities often seek spouses from other villages, creating networks of mutual hospitality and reducing inter-village hostility. Affinal relationships are characterized by avoidance, including prohibitions on speaking names, direct address, and sharing food—considered akin to sexual contact. In non-exchange marriages, the bride-receiving group is viewed as subordinate to the bride-giving group.

Betrothal traditionally took place before either partner reached sexual maturity. In the bachelors’ hut system, the fiancées of boys in the higher grades could be used by older men to “raise” sperm for ritual purposes. Older boys were expected to have sexual relationships with several “sweethearts” before marriage, but not with their future wives.

Inheritance is through the male line. The eldest surviving brother inherits his father’s gardens, followed sequentially by his younger brothers. When the last brother dies, the gardens pass to the next generation. Everyday items made by the deceased are buried or destroyed, and ceremonial crops and owned trees are likewise destroyed upon a man’s death. European goods may be inherited by sons or daughters.

Kimaam Child Rearing and Growing Up

Once a woman knows she is pregnant, both spouses follow a series of taboos intended to protect the unborn child from sorcery and from gardening magic. Childhood is marked by feasts celebrating stages of growth and increasing independence; many of these ceremonies can only be performed during the final mortuary feast of a sector member. With each feast, certain taboos on parents and children are lifted. [Source: J. Patrick Gray, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September, 2019]

Women bear primary responsibility for childcare, though men participate as well. Children accompany their parents everywhere, and learning occurs informally through observation rather than instruction. Parents do not pressure children to contribute to subsistence tasks; Serpenti characterizes childhood as highly permissive. Corporal punishment is avoided, and reluctance to send children to school partly reflects disapproval of teachers’ use of physical discipline.

Girls gradually take on household tasks as they mature. At first menstruation, they don the pubic apron for the first time—an event marked by a women-only feast. Girls are taught that menstrual blood is harmful to men and to growing crops. Some western villages maintain menstrual huts; elsewhere, women simply move to a separate corner of the house.

Bachelors’ Huts (Burawa) have traditionally been part of growing up for boys. Between ages ten and fourteen, boys traditionally entered the burawa, although the system ended about twenty years before Serpenti’s fieldwork and is known through informants’ recollections. Entry occurred only during the final mortuary feast of a sector member and was symbolically equated with the boy’s social death. Each novice was assigned a mentor from the second grade of the hut.

The mentor made ritual incisions on the boy’s arms, legs, and abdomen, which were then repeatedly smeared with sperm—the source of power in gardening magic and headhunting. Men renowned for successful ceremonial crop cultivation or for taking heads were believed to have especially potent sperm. Mentors supplied their own betrothed to older men to produce this ritual substance. After about a year, the novice became a mentor to a new initiate. Boys spent several years in the burawa, leaving when ready to marry. While in seclusion, they learned agricultural skills, magical chants, myths, and accounts of past headhunting raids. In Ndom-speaking villages, bachelor huts did not exist; initiation centered on a bull-roarer cult, and boys spent only a few weeks in isolation.

Sexual Rituals in the Past: “Growing Up Sexually”: One striking feature of Kimaam villages in the 1980s was the ubiquity of periodic ceremonials and magical rites in which older men engaged in ritualized sexual intercourse with newly initiated boys and underage girls. Such "ritualized homosexuality and pedophilia" practices were important to the structural duality of Kimaam society, including deep-seated emic distinctions people made between the contrasting roles of women and men regarding life and death. The Kimaam regard women as producers of life that is destined to die. By contrast, men produce life out of death, as revealed in men's ability to foster the productivity of yams through ritual. This power is reiterated in older men's claim to engineer men with socially-desired qualities out of young boys through the transfer of sperm from older men to young boys, either directly through sexual contact or by massaging their bodies with sperm previously collected with the help of young girls. These acts are justified as the desire to perpetuate the ritual, as well as to maintain masculine potency and power by distancing mature men from the impurity and danger of adult women and menstrual blood. The custom of semen transfer is covered by Serpenti (1984) and Gray (1986). [Source:“Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, September 2004]

Kimaam Society and Political Organization

The basic social unit in Kimaam society is the dwelling island (patha). Several patha form a village ward (kwanda), which can mobilize labor for large projects such as creating garden islands, building canoes, or organizing group hunts or fishing. Wards are grouped into two ceremonially opposed village sectors (paburu). Although the sectors cooperate during major rituals—bachelors’ hut initiations, mortuary ceremonies, and ndambu competitive feasts—they also compete fiercely in canoe building, dancing, and wrestling, often leading to physical fights. No larger political units exist beyond the village. Government resettlement weakened the importance of the patha and kwanda, but the dualistic paburu system remained strong. The Kimaam maintain Lemaskim, the Kimaam Indigenous Peoples Institute, dedicated to safeguarding local customs and cultural heritage. [Source: J. Patrick Gray, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September, 2019]

Kinship is not usually traced beyond the grandparent generation, and descent is bilateral. Because ward and sector identities dominate social life, kinship alone governs few activities. The primary kin units are sets of real or classificatory siblings (jaeentjewe), and the jaeentjewe of ego’s parents, ego, and ego’s children form a broader grouping called tjipente. Cooperation within these kin groupings helps bridge antagonisms between wards and sectors. Adoption is common: boys may be adopted to tend and inherit gardens or care for aging parents, while girls are often adopted to facilitate sister-exchange marriages. Marital residence is virilocal.

Kinship Terminology is Hawaiian, distinguishing between older and younger siblings. This relative-age distinction extends to cousins based on actual age, not parental birth order. Ndom-speaking villages differ, using an Iroquois system for cross-cousins that highlights the special relationship between a mother’s brother and a sister’s children.

Political Authority rests on the ability to mobilize men for competitive feasts. Success in cultivating ceremonial crops depends on mastery of gardening magic. Men who excel become great cultivators (warrewundu), providing magical medicines, deciding the timing of rituals, and distributing food and wati (kava) at feasts. Their influence extends beyond agriculture, and they act as spokesmen in disputes. Warrewundu may challenge one another to ndambu competitions to increase prestige. Women are excluded from this path due to their perceived danger to ceremonial crops, and younger men rarely possess the required agricultural skill. Men who have taken heads in raids also hold high status.

Villages typically view one another with suspicion, particularly fearing sorcery. Neighboring villages may establish peace through trade or marriage, while others alternate between headhunting raids and competitive feasting. Exchanges of children between headhunters were sometimes used to secure peace. Men avoided traveling outside the village in small groups due to fear of ambush. Within a village, sectors may clash over sorcery accusations, elopements, or adultery; such conflicts are resolved through dancing, wrestling, hunting, ndambu competitions, or open fighting.

Kimaam Daily Life and Health

The Kimaam live primarily by hunting, gardening, and fishing in the swampy lowlands of their island, most of which lies below 100 meters in elevation. Travel is easiest by boat, though Kimaam has an airstrip and a road connecting it to Padua; elsewhere, people rely on canoes or travel on foot. Adults require small canoes for daily travel between dwelling islands and nearby gardens; these are used so heavily that they last only a year or two. Larger canoes, jointly owned and used for inter-village travel, are more durable. [Source: Joshua Project, Wikipedia; J. Patrick Gray, eHRAF World Cultures, Yale University, September 2019]

Men construct and maintain both garden islands and dwelling islands, including all buildings. Women assist by towing drift grass to new sites, but men handle the layering required to raise an island’s surface. Only men plant, tend, and harvest root crops because the associated garden magic is considered dangerous to women, though women may help harvest cassava. Men perform all ritual work related to gardening and healing. They also manage sago stands—felling trees and removing the pith—while women pound the pith into flour. Women gather and process mapiè ferns. Men make canoes, tools, utensils, and drums; women make oven bricks and gather firewood. Hunting is primarily male, while women help transport game. Both sexes fish with poison. Men also spear and shoot fish; women use nets, hooks, and traps. Women catch water snakes. Cooking and childcare are mainly women’s responsibilities, though men often assist. Women raise pigs, but only men may slaughter them.

Yos Sudarso Island onsists of lowland swamp rich in forest and fishery resources. Unlike many other groups in South Papua who depend heavily on forest products, the Kimaam both process sago and maintain gardens producing taro, sweet potatoes, bananas, and other crops—many of which are displayed each year during the Ndambu festival. Machetes are used for many daily tasks, and bows and arrows remain important for hunting. Houses are typically gubuk-style structures built on stilts, roofed with pleated sago leaves or other local materials. Infrastructure includes SSB radio communication and evening electricity from PLN in Kimaam town. People generally identify themselves by their home village. Around the district capital, residents draw drinking water from wells.

Plastic arts on Kimaam are limited, mostly to plaited mats and small ornaments. Men carve drums, and large canoes were traditionally painted and decorated with croton leaves. Body painting is a significant expressive form, with boys adopting distinctive color patterns as they progress through the bachelors’ hut. Traditional personal adornment was limited. Adult men wore a small coconut covering or only a penis string, while older boys in bachelors’ huts used large seashells. Women wore a rush apron. Rattan anklets and armlets, nose and ear ornaments, and hairpieces (now discontinued) were also made. Hunting and fishing equipment included bamboo spears, bows and arrows, throwing clubs, nets, and fish dams. Men crafted drums, and Ndom-speaking villages produced bullroarers for initiation rites.

Malaria is widespread in the swampy environment, and skin diseases and dietary deficiencies are common health concerns. Several clinics serve the area. Serious illness and death are attributed to sorcery or contact with powerful garden magic. Minor ailments may be treated by bleeding or burning, but persistent symptoms lead families to consult a sorcerer (undani). In grave cases, the undani identifies the responsible sorcerer and attempts to lift the spell, sometimes by administering a mixture of sperm and coconut milk, which was believed to have healing properties. During epidemics, sorcerers and influential men selected women to “raise” sperm that was then smeared on poles at village entrances and on villagers themselves. The practice of young girls engaging in serial intercourse with older men for these ritual purposes—also performed before headhunting raids and in bachelors’ hut ceremonies—led to high rates of venereal disease, which declined rapidly after the custom ended.

Kimaam Villages and Houses

Villages consist of artificial islands built from clay, drift grass, and mud. The fundamental unit is the patha, or dwelling island, which may house a single nuclear family but more often includes several related families—typically a father and his married sons, or a set of brothers. Each patha is linked to numerous garden islands used for cultivation: smaller villages may have dozens, while larger ones maintain hundreds. Families can establish independence by constructing a new dwelling island. A cluster of connected patha forms a kwanda (village ward). Several kwanda together make up a paburu (village sector), and most villages consist of two paburu that stand in a formally antagonistic ceremonial relationship. In larger settlements, wards within the same paburu may also engage in competitive ritual rivalry. [Source: J. Patrick Gray, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September, 2019]

Coastal settlements lie on or near rivers, while inland communities in the central swamp are built beside small lakes that provide fishing grounds. Village populations vary from under 100 to more than 700 people; the largest settlements tend to occupy areas with more dry land and less seasonal flooding.

Each dwelling island traditionally held a pair of structures: a simple daytime shelter with a sago or nipah–leaf roof and no walls, and a paia, a beehive-shaped, water- and mosquito-proof night house made from sago leaves, rattan, and dried grass. The paia had an upper loft for sleeping and food storage. House forms varied somewhat across the island, especially on the west and south coasts. Government pressure led to the abandonment of the paia, and by the 1960s it had largely disappeared from most villages.

Each paburu formerly maintained its own burawa (bachelors’ hut), an enlarged paia requiring a substantial dwelling island. Members of one paburu were prohibited from entering the burawa of the other. In large villages, individual wards sometimes built their own burawa as well. The initiation rites associated with these bachelors’ huts had disappeared by the 1940s.

Kimam Agriculture and Economic Activity

The Kimaam practice an intensive form of agriculture centered on man-made garden islands built in the swamp. These islands are constructed on beds of cut reeds overlaid with alternating layers of drift grass and clay taken from the surrounding water. Deep ditches, two to three meters across, are dug around each island, and layers of clay and grass are continually added to maintain both fertility and structural strength. Garden islands are typically narrow—often less than three meters wide—and gardeners rotate crops or leave islands fallow between planting seasons. Villages lacking sufficient swamp space build raised gardens of clay, compost, and sand on higher ridges, sometimes located hours away by boat. [Source: J. Patrick Gray, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University, September, 2019]

Main root crops include yams, taro, sweet potatoes, and cassava. Yams hold the highest prestige because of their role in competitive feasting, though taro is the more common staple in most villages. In the southern regions, sweet potatoes replace yams in both everyday consumption and ceremonial use. Cassava, a recent introduction, has little ritual significance. Garden islands also support sago, coconut, and banana trees. Sago is more abundant in the east, and western villages often trade pigs for sago. Kava—called wati—is an important intoxicant consumed socially, and tobacco and areca nut are also cultivated. Many wild swamp plants are eaten, especially mapiè, a fern ground into flour and widely consumed during food shortages.

Hunting provides wild pigs, kangaroos, cassowaries, and smaller animals such as lizards, rats, snakes, and birds. Eggs, ant larvae, grasshoppers, and sago grubs supplement the diet. Fishing practices vary by region: tidal-river villages use poisons year-round, while interior communities rely on seasonal fishing—hunting water snakes in the rainy season and trapping fish as water levels fall in the dry season. People also collect turtles, crabs, shrimp, and crocodiles. Pig ownership is limited, generally fewer than one per household. Food shortages are common, and Serpenti described local nutrition as precarious. Southern villages experience famine every five to seven years due to tidal waves, while early rains may trigger scarcity inland.

Trade between villages followed ecological patterns: sago and canoe timber were the major exchange goods. Plaited mats, dog-tooth strings, and nautilus shells served as barter items and were used in bride-price payments. Missionaries later facilitated the sale of mats in Merauke. The most important manufactured item is the dugout canoe. Villages lacking suitable timber acquire canoes through trade, often exchanging sago or European goods.

Land Tenure is relatively egalitarian. The reed marsh surrounding a village is collectively owned. Each village sector controls a defined portion of this communal land, which all sector members may use for fishing, hunting, and gathering. Individuals gain temporary rights to specific sites through labor investment, but these rights lapse when use ends. Women retain use rights in the sectors of their birth. Garden islands are owned by the ward, with each ward controlling a planting zone (paku). Within the paku, men create new garden islands wherever they choose. A man’s gardens pass to his sons, with the eldest son supervising the holdings for his siblings. Inheritance follows the sibling set: gardens transfer to the next brother upon the death of the eldest, and only after the youngest brother dies are the gardens passed to the next generation. The same rules apply to sago and coconut groves. Women cannot inherit garden islands.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Geographic,, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Encyclopedia.com, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025