KOROWAI PEOPLE

The Korowai are a semi-nomadic people known for their small size, treehouses and cannibalism. The Korowai are about the same size as African pygmies— most are less than 1.5 meters (five feet) tall. Most live in a 1,550 square kilometer (600 square mile) tract of swampy forest in southwestern Papua in the Indonesian part of New Guinea . Even though they are few in number their homeland not in immediately threatened because it lacks oil, precious minerals and commercial valuable trees. In the rain forest where the Korowai live it can take all day to cover five miles on land and four hours to travel two miles up a rain-swollen river. [Source: George Steinmetz, National Geographic, February, 1996 ^^]

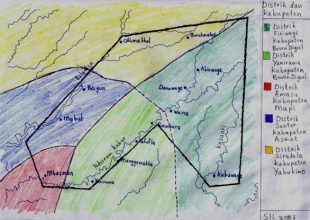

The Korowai, also called the Kolufo, live in southwestern Papua about 160 kilometers inland from the Arafura Sea, where the Asmat live and Michael Rockefeller disappeared in 1961, in the dense rainforests of Boven Digoel, Mappi, Asmat, Pegunungan Bintang, and Yahukimo regencies in the Indonesian provinces of South Papua and Highland Papua. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Korowai population in the 2020s was 4,500. Other sources estimate their population is be between 3,000 and 4,400 people, with many remaining unregistered due to the difficulty of accessing their remote locations.

The Korowai call themselves Klufo-fyumanop or Kolufo-yanop. The word "Kolufo" means "people," and "fyumanop" means "walking on leg bone." This name distinguishes them from the Citak and the Auyu, who use boats to travel. The Korowai language belongs to the Awyu–Dumut family in southeastern Papua and is part of the Trans–New Guinea phylum. A dictionary and grammar book were produced by a Dutch missionary linguist. [Source: Wikipedia]

Paul Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Most Korowai still live with little knowledge of the world beyond their homelands and frequently feud with one another. Some are said to kill and eat male witches they call khakhua. Traditionally, they have lived in treehouses, in groups of a dozen or so people in scattered clearings in the jungle; their attachment to their treehouses and surrounding land lies at the core of their identity. [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2006 \=]

Book: “Among the Cannibals: Adventures on the Trail of Man's Darkest Ritual” by Paul Raffaele (Smithsonian, 2008)]

RELATED ARTICLES:

KOROWAI LIFE AND SOCIETY: RELIGION, FOOD AND TREEHOUSES factsanddetails.com

ASMAT AND KOROWAI COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

ASMAT CULTURE: MUSIC, FOLKLORE, CEREMONIES, BODY ADORNMENT factsanddetails.com

ASMAT ART: BIS POLES, SPIRIT CANOES, BODY MASKS factsanddetails.com

ASMAT: HISTORY, RELIGION AND HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

ASMAT LIFE: SOCIETY, MARRIAGE, FOOD, VILLAGES, WORK factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SOUTHERN LOWLANDS OF PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

MARIND PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (SOUTHWEST NEW GUINEA, INDONESIA) factsanddetails.com

KIMAM PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

Korowai Contacts with Westerners

The Korowai were largely ignored by the outside world until the 1970s. The first documented contact between Westerners and members of a Western Korowai (or Eastern Citak) band occurred in March, 1974. The expedition was co-led by anthropologist Peter Van Arsdale (now at the University of Denver), geographer Robert Mitton, and community developer Mark (Dennis) Grundhoefer. They encountered thirty men on the south bank of the Upper Eilanden River, approximately 20 kilometers (twelve miles) east of its junction with the Kolff River and six kilometers (ten miles) north of the Becking River. The researchers generated a basic word list and recorded observations regarding fire-making techniques and other topics. [Source: Wikipedia]

Dutch Missionaries from the Dutch Reformed church tried to convert the Korwai to Christianity. The Rev. Johannes Veldhuizen,made contact with the Korowai in 1978 and aborted his plans to convert them to Christianity. "A very powerful mountain god warned the Korowai that their world would be destroyed by an earthquake if outsiders came into their land to change their customs," he said. "So we went as guests, rather than as conquerors, and never put any pressure on the Korowai to change their ways."

Another Dutch missionary, Gerrit van Enk co-authored the study “The Korowai of Papua.” He spent 10 years with the Korowai people in humid lowland forest near the upper Becking River and failed to convert a single member of the tribe. Van Enk, coined the term "pacification line" for the imaginary border separating Korowai clans accustomed to outsiders from those farther north. He said he never went beyond the pacification line because of possible danger from Korowai clans there hostile to the presence of laleo [outsiders] in their territory. [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2006 \=]

A small Christian community was founded nearby in 1996, mainly by neighboring Kombai people. Although the Korowai had long been considered highly resistant to religious conversion, the first baptisms took place in the late 1990s. In 2003, a Wycliffe/SIL translation team established a base in Yaniruma. Today, Korowai clans living near government-supported villages have adopted some new customs and maintain limited contact with visitors, while more remote groups continue to follow largely traditional ways of life.

Korowai Cannibalism

Some people say the Korowai are among the last people on earth to practice cannibalism. Outsiders are almost never invited in their homes and some people speculate this is because they have human bones hidden inside but most likely they just don't their privacy invaded. Among the Korowai cannibalism has traditionally been part of their justice system. Hallet said: They only practiced cannibalism in the recent past when someboady murdered somebody, stole somebody’s else’s wife or something important to their food system. Anthropologists suspect that cannibalism is no longer practiced by the Korowai clans that have had frequent contact with outsiders. There have been reports that certain clans have been coaxed into encouraging tourism by perpetuating the myth that cannibalism is still actively practiced. [Source: Wikipedia, Thomas O'Neill, National Geographic, February, 1996,☼]

Raffaele visited the Korowai to investigate reports about their cannibalism. In a review of Raffaele’s book “Among the Cannibals: Adventures on the Trail of Man's Darkest Ritual,” Richard Grant wrote in the Washington Post, “Lacking any knowledge of germs and microbes, the Korowai ascribe all deadly illness to witchcraft, and a dying Korowai will whisper the name of the khakhua, or male witch, who is responsible. It will be a man they all know who has been invaded by the evil khakhua spirit, and he must now be killed, cut into pieces, roasted in leaves and eaten. Raffaele doesn't actually witness any cannibalism...but he gathers plenty of interesting detail. The Korowai say the meat tastes good, similar to a young cassowary (an ostrichlike bird), and the best parts are the brain and the tongue. Raffaele asks them if they also eat their enemies, and they are appalled. "We don't eat humans," they assure him; "we only eat khakhuas." [Source: Richard Grant, Washington Post, July 30, 2008]

“After we eat a dinner of river fish and rice,” Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: A Korowai named Boas “explains why the Korowai kill and eat their fellow tribesmen. It's because of the khakhua, which comes disguised as a relative or friend of a person he wants to kill. "The khakhua eats the victim's insides while he sleeps," Boas explains, "replacing them with fireplace ash so the victim does not know he's being eaten. The khakhua finally kills the person by shooting a magical arrow into his heart." When a clan member dies, his or her male relatives and friends seize and kill the khakhua. "Usually, the [dying] victim whispers to his relatives the name of the man he knows is the khakhua," Boas says. "He may be from the same or another treehouse." [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2006 \=]

“The killing and eating of khakhua has reportedly declined among tribespeople in and near the settlements. Rupert Stasch, an anthropologist at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, who has lived among the Korowai for 16 months and studied their culture, writes in the journal Oceania that Korowai say they have "given up" killing witches partly because they were growing ambivalent about the practice and partly in reaction to several incidents with police. In one in the early '90s, Stasch writes, a Yaniruma man killed his sister's husband for being a khakhua. The police arrested the killer, an accomplice and a village head. "The police rolled them around in barrels, made them stand overnight in a leech-infested pond, and forced them to eat tobacco, chili peppers, animal feces, and unripe papaya," he writes. Word of such treatment, combined with Korowais' own ambivalence, prompted some to limit witch-killing even in places where police do not venture. Still, the eating of khakhua persists, according to my guide, Kembaren. "Many khakhua are murdered and eaten each year," he says, citing information he says he has gained from talking to Korowai who still live in treehouses.” \=\

Taylor, the Smithsonian Institution anthropologist, described khakhua-eating as "part of a system of justice." Later Raffaele’s guide Kembaren “brings to the hut a 6-year-old boy named Wawa, who is naked except for a necklace of beads. Unlike the other village children, boisterous and smiling, Wawa is withdrawn and his eyes seem deeply sad. Kembaren wraps an arm around him. "When Wawa's mother died last November—I think she had TB, she was very sick, coughing and aching—people at his treehouse suspected him of being a khakhua," he says. "His father died a few months earlier, and they believed [Wawa] used sorcery to kill them both. His family was not powerful enough to protect him at the treehouse, and so this January his uncle escaped with Wawa, bringing him here, where the family is stronger." Does Wawa know the threat he is facing? "He's heard about it from his relatives, but I don't think he fully understands that people at his treehouse want to kill and eat him, though they'll probably wait until he's older, about 14 or 15, before they try. But while he stays at Yafufla, he should be safe." \=\

Hanging Out with Korowai Cannibals

Paul Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “On our third day of trekking, after hiking from soon after sunrise to dusk, we reach Yafufla, another line of stilt huts set up by Dutch missionaries. That night, Kembaren takes me to an open hut overlooking the river, and we sit by a small campfire. Two men approach through the gloom, one in shorts, the other naked save for a necklace of prized pigs' teeth and a leaf wrapped about the tip of his penis. "That's Kilikili," Kembaren whispers, "the most notorious khakhua killer." Kilikili carries a bow and barbed arrows. His eyes are empty of expression, his lips are drawn in a grimace and he walks as soundlessly as a shadow. [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2006 \=]

“The other man, who turns out to be Kilikili's brother Bailom, pulls a human skull from a bag. A jagged hole mars the forehead. "It's Bunop, the most recent khakhua he killed," Kembaren says of the skull. "Bailom used a stone ax to split the skull open to get at the brains." The guide's eyes dim. "He was one of my best porters, a cheerful young man," he says. Bailom passes the skull to me. I don't want to touch it, but neither do I want to offend him. My blood chills at the feel of naked bone. \=\

“Around our campfire, Bailom tells me he feels no remorse. "Revenge is part of our culture, so when the khakhua eats a person, the people eat the khakhua," he says. "It's normal," Bailom says. "I don't feel sad I killed Bunop, even though he was a friend." In cannibal folklore, told in numerous books and articles, human flesh is said to be known as "long pig" because of its similar taste. When I mention this, Bailom shakes his head. "Human flesh tastes like young cassowary," he says, referring to a local ostrich-like bird. At a khakhua meal, he says, both men and women—children do not attend—eat everything but bones, teeth, hair, fingernails and toenails and the penis. "I like the taste of all the body parts," Bailom says, "but the brains are my favorite." Kilikili nods in agreement, his first response since he arrived. \=\

When the khakhua is a member of the same clan, he is bound with rattan and taken up to a day's march away to a stream near the treehouse of a friendly clan. "When they find a khakhua too closely related for them to eat, they bring him to us so we can kill and eat him," Bailom says. He says he has personally killed four khakhua. And Kilikili? Bailom laughs. "He says he'll tell you now the names of 8 khakhua he's killed," he replies, "and if you come to his treehouse upriver, he'll tell you the names of the other 22." \=\

“I ask what they do with the bones. "We place them by the tracks leading into the treehouse clearing, to warn our enemies," Bailom says. "But the killer gets to keep the skull. After we eat the khakhua, we beat loudly on our treehouse walls all night with sticks" to warn other khakhua to stay away. As we walk back to our hut, Kembaren confides that "years ago, when I was making friends with the Korowai, a man here at Yafufla told me I'd have to eat human flesh if they were to trust me. He gave me a chunk," he says. "It was a bit tough but tasted good." \=\

Account of Korowai Cannibalism

Paul Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: ““The fire's reflection flickers on the brothers' faces as Bailom tells me how he killed the khakhua, who lived in Yafufla, two years ago. "Just before my cousin died he told me that Bunop was a khakhua and was eating him from the inside," he says, with Kembaren translating. "So we caught him, tied him up and took him to a stream, where we shot arrows into him." Bailom says that Bunop screamed for mercy all the way, protesting that he was not a khakhua. But Bailom was unswayed. "My cousin was close to death when he told me and would not lie," Bailom says.[Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2006 \=]

“At the stream, Bailom says, he used a stone ax to chop off the khakhua's head. As he held it in the air and turned it away from the body, the others chanted and dismembered Bunop's body. Bailom, making chopping movements with his hand, explains: "We cut out his intestines and broke open the rib cage, chopped off the right arm attached to the right rib cage, the left arm and left rib cage, and then both legs." The body parts, he says, were individually wrapped in banana leaves and distributed among the clan members. "But I kept the head because it belongs to the family that killed the khakhua," he says. "We cook the flesh like we cook pig, placing palm leaves over the wrapped meat together with burning hot river rocks to make steam." \=\

“Some readers may believe that these two are having me on—that they are just telling a visitor what he wants to hear—and that the skull came from someone who died from some other cause. But I believe they were telling the truth. I spent eight days with Bailom, and everything else he told me proved factual. I also checked with four other Yafufla men who said they had joined in the killing, dismembering and eating of Bunop, and the details of their accounts mirrored reports of khakhua cannibalism by Dutch missionaries who lived among the Korowai for several years. Kembaren clearly accepted Bailom’s story as fact.” \=\

Korowai and the Modern World

In recent years the Indonesian government has tried to get the Korowai to move from the forest and settle in towns. Some now wear shorts and shirts and they definitely have developed a taste for tobacco. Some Korowai have moved to settlements established by Dutch missionaries and some tourists have ventured into Korowai lands. But in the deep rain forest one goes many the Korowai cling to their traditional ways. When asked if he wanted to move to a settlement, one Korowai man told National Geographic, "We don't want to leave the forest. My wife is afraid of the town, and I don't like that the houses are so close together. I don't like that a stranger gives us orders and tells us what to do." [Source: George Steinmetz, National Geographic, February, 1996]

Since 1980, some Korowai have moved into the recently opened villages of Yaniruma at the Becking River banks (Kombai–Korowai area), Mu, and Mbasman (Korowai–Citak area). In 1987, a village was opened in Manggél, in Yafufla (1988), Mabül at the banks of the Eilanden River (1989), and Khaiflambolüp (1998). The village absenteeism rate is still high, because of the relatively long distance between the settlements and the food (sago) resources. [Source: Wikipedia]

On his departure from the Korowai region, Paul Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Before I leave, Khanduop wants to talk; his son and Kembaren translate. "Boas has told me he'll live in Yaniruma with his brother, coming back just for visits," he murmurs. Khanduop's gaze clouds. "The time of the true Korowai is coming to an end, and that makes me very sad." Boas gives his father a wan smile and walks with me to the pirogue for the two-hour journey to Yaniruma, wearing his yellow bonnet as if it were a visa for the 21st century. [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian Magazine, September 2006 \=]

“Three years earlier I had visited the Korubo, an isolated indigenous tribe in the Amazon, together with Sydney Possuelo, then director of Brazil's Department for Isolated Indians . This question of what to do with such peoples—whether to yank them into the present or leave them untouched in their jungles and traditions—had troubled Possuelo for decades. "I believe we should let them live in their own special worlds," he told me, "because once they go downriver to the settlements and see what is to them the wonders and magic of our lives, they never go back to live in a traditional way." \=\

“So it is with the Korowai. They have at most a generation left in their traditional culture—one that includes practices that admittedly strike us as abhorrent. Year by year the young men and women will drift to Yaniruma and other settlements until only aging clan members are left in the treehouses. And at that point Ginol's godly prophecy will reach its apocalyptic fulfillment, and thunder and earthquakes of a kind will destroy the old Korowai world forever.” \=\

Korowai, Anthropologist and the Western Media

Smithsonian Institution anthropologist Paul Taylor studied the Korowai and made the 1994 documentary “Lords of the Garden” about them. It was connected with his anthropological study in the Dayo village area and documented Korowai treehouse construction and the use of cannibalism as a form of criminal justice. [Source: Wikipedia]

Dea Kembaren, a Sumatran anthropologist who came to Papua around 1990 first visited the Korowai in 1993, and came to know much about their culture, including some of their language. He made several documentary films on the Korowai for Japanese television.

Media interest continued to grow. In 2006, writer Paul Raffaele brought an Australian 60 Minutes crew to the region. The 2007 BBC documentary First Contact featured presenter Mark Anstice’s 1999 encounter with the Korowai, who were unsettled by the arrival of a “white ghost,” believed to herald the end of the world. For the BBC’s Human Planet (2011), Korowai builders constructed a 35-meter-high treehouse.

In 2019 the YouTube channel Best Ever Food Review Show visited to explore local foods. The documentary My Year with the Tribe later revealed how a small industry had developed around the Korowai’s reputation for living an untouched, traditional life. Some villagers constructed unusually high treehouses with financial support from visiting film crews, and staged “traditional” scenes for outsiders.

Kombai

The Kombai are a tree-dwelling people with a culture similar to that of the Korowai, but their language is very different. Families, dogs and piglets all live together in Kombai tree houses. Men and women usually stay in separate areas defined by different hearths. Sexual relations are usually not allowed inside the treehouses. [Source: George Steinmetz, National Geographic, February, 1996 ^^]

Describing one of his first encounters with the Kombai people, Steinmetz wrote: "I was eating a lunch of tinned biscuits and tea when a shrill cry rose from the far side of the clearing. I glanced up just as two naked men burst into view and came dashing towards us, fitting large barbed arrows to their bows. Our porters halted them, bows drawn just yards a way. Angry words flew, then quieted as my interpreter offered them gifts and greetings. I soon learned they were father and son, that we were the first outsiders they had ever seen, and that they intended to kill us." ^^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025