ASMAT CULTURE AND SPORTS

Asmat art, oral literature and music are closely associated with rituals and ceremonies and are closely bound to ceremonial and socioeconomic cycles. Many ritual feasts feature the chanted reading of epic poems that sometimes last for several days. They are often about legendary, mythical or real life heroes.

Master carvers (wowipits) are recognized around the world. The ancestor poles, war shields, and canoe prows they produce are characterized by their exuberant form, shape, and colors. characterizes. Drums and head-hunting horns are considered sacred, though singing is the only form of music. Music serves as a vehicle for possession, social bonding, political oratory, therapy, cultural transmission, and recreation. [Source: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

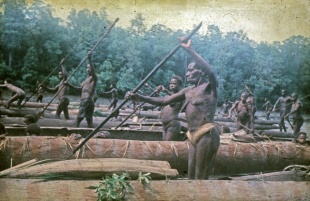

Dugout canoe races are major events and are often featured at celebrations. Traditionally, male competition among the Asmat was intense. This competition centered on demonstrating male prowess through success in headhunting, acquiring fishing grounds and sago palm stands, and cultivating a large network of feasting partners. Men still compete in these areas, except for headhunting, which is now illegal.[Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

During the Asmat mask feast a man dressed in a weird costume with a rattan cone head and palms streamers bursts out of the woods at dawn to chase children. Later children get up enough courage to fling toy arrows at the beast who later still goes trick or treating from house to house. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ASMAT ART: BIS POLES, SPIRIT CANOES, BODY MASKS factsanddetails.com

ASMAT: HISTORY, RELIGION AND HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

ASMAT LIFE: SOCIETY, MARRIAGE, FOOD, VILLAGES, WORK factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI PEOPLE: HISTORY, CANNIBALISM, CONTACT WITH WESTERNERS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI LIFE AND SOCIETY: RELIGION, FOOD AND TREEHOUSES factsanddetails.com

ASMAT AND KOROWAI COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SOUTHERN LOWLANDS OF PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

MARIND PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (SOUTHWEST NEW GUINEA, INDONESIA) factsanddetails.com

KIMAM PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

Books: “The Asmat of New Guinea” by Michael Rockefeller (1967); “Embodied Spirits: Ritual Carvings of the Asmat. Exhibition catalogue” by Tobias Schneebaum, Peabody Museum, 1990; “Asmat Art: Woodcarvings of Southwest New Guinea” edited by Dirk Smidt (1993)

Asmat Folklore and Mythology

The Asmat did not have access to written literature since their language was exclusively oral. However, they have an extensive body of oral literature. Epic songs, which often lasted several days, and metaphorical love songs remain important forms of expression among the Asmat. *

Describing an Asmat man recounting what happened around the time Michael Rockefeller disappeared, Carl Hoffman wrote in “Savage Harvest”:“The Asmat, living without TV or film or recording media of any kind, are splendid storytellers. During a disjointed swirl of story, Kokai pantomimed the pulling of a bow. He slapped his thighs, his chest, his forehead, then swept his hands over his head, illustrating the back of his head blowing off. His eyes went big to show fright; he showed running with his arms and shoulders, then slinking, creeping into the jungle. [Source: Carl Hoffman, Smithsonian Magazine, March 2014]

Many Asmat myths relate to their head-hunting tradition. In their origin story, two brothers were the first inhabitants of Asmat land. The elder persuaded the younger to cut off his head, after which the severed head instructed him in the practice of headhunting, the preparation of trophy heads, and their use in male initiation rituals. The younger brother also inherited the elder’s name—a pattern echoed in the tradition of an Asmat warrior taking the name of the person he has decapitated. The number of names a man carries marks the number of heads he has taken. Reflecting the spiritual power attributed to the dead, the skulls of relatives were also kept as protective talismans against malevolent spirits. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

In the beginning, according to the Asmat creation myth, a corpse of a man floating in the sea was brought to life by a great bird. In a previous life the man had seduced his brother's wife and was banished from his community and drowned when his boat capsized during his escape. On returning to life he floated to the land where the Asmat live today. But there was on one there and he grew bored. He tried bring to life some statues he carved but no luck, finally the spirit told him to go into the jungle to seek out the "tree woman."

The man was told to chop off the tree woman's head and return it to village where it would bring the statues he made to life. The man did what he was told. The spirit was right and soon the statues were dancing around to his delight. Then, one day a crocodile showed up and it and the man engaged in a horrible battle. The man eventually emerged the winner but he was so angry he chopped the crocodile in three pieces: one he hurled so far it lost its color. This produced the white race. Another was tossed a little less hard so it lost only part of its color. This produced men with brown skin. The third was left where it was giving rise to black men.

Asmat Music

Music and singing are regarded by Asmat as vehicles of social bonding, recreation and spirit possession. The only musical instruments used by the Asmat are drums, which are beaten in a regular rhythm to accompany songs that are part of all ceremonies and feasts. Asmat drums and headhunting horns are regarded as sacred but the horns are not really used when making music.

The Asmat do not consider instrumental sounds to be music. In Asmat culture, only singing is classified as music. Love songs and epic songs, which can take several days to perform, remain important forms of expression. Traditionally, dance was an integral part of Asmat ceremonial life. However, missionaries have discouraged it.[Source:A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Drums have traditionally been made from lizard skin fastened to a hollow log with glue made from human blood. The drum maker often volunteered to supply the blood from an incision made in his leg. The blood is collected in clam shells and mixed with baked seashell to produce the glue. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972 =]

Two Asmat bamboo horns in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection were made in the mid-20th-century in the Pomatsj and Assuwe River regions. The first horn, created by the artist Tep of Sauwa village on the Pomatsj River, measures 42.2 centimeters (16.6 inches). The second, made by Shuw of Amanamkai village in the Assuwe River region, is slightly smaller at 38.7 centimeters (15.25 inches)

Asmat Drums

Asmat drums are similar in shape to drums produced in other parts of New Guinea and Melanesia. They have an hourglass shape and a single, lizard skin-covered head that is struck with the palm of the hand. The other hand is used to hold the drum by a carved handle. According to Asmat mythology the hero Fumeripits made the first carvings of men and women and placed them in the first men's ceremonial house. By beating on his drum, Fumeripits caused the figures to dance, bringing them to life. [Source: “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, Inc., 1999]

Lizard-skin tympanums (drum heads) are attached to the drums with an adhesive mixture of lime and human blood. Handles are elaborately carved, usually with images of relatives and the heads of parrots and cockatoos. One drum in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made by Chief Omas in the mid-20th century from wood, lizard skin, beeswax, sago palm leaves, fiber, paint and human blood. It originates from Sauwa village in the Pomatsj River region and measures 57.8 × 31.8 × 24.1 centimeters (22.75 inches high, with a width of 12.5 inches and a depth of 9.5 inches. The figure on this particular work probably represents the father of the owner. The designs on the base of the drum depict the shell-nose ornaments worn by Asmat warriors.

Another Asmat drum in Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made by an artist named

Ema in mid-20th century from wood, lizard skin, fiber, beeswax and blood. It was made in Agani village on a northern tributary of the , Pomatsj River and 61 centimeters (24 inches) long.

A drum made by Ojapit originates from Weo (Wejo) village on a northern tributary of the , Pomatsj River and measures 81.6 x 21 centimeters (32.12 inches long and 8.25 inches wide). A drum made by Jomor from Jufri village on Unir (Undir) River is 53.3 centimeters (21 inches long.

Asmat Clothes and Body Ornaments

Traditionally, the Asmat wore little or no clothing. Most people went barefoot, and footwear was uncommon. Women typically wore fiber skirts, while men were usually unclothed. In the eastern Asmat region, men wore rattan waistbands and a small hollow tube as a penis covering, along with plaited cane bands around the wrists and below the knees. Missionary and government influence has led many Asmat today to adopt Western-style clothing—rugby shorts for men and floral cotton dresses for women. Some traditional adornments, however, remain in use. Men may still wear headdresses and wild pig or boar tusks inserted through a pierced nasal septum during feasts and special occasions.. Women sometimes wear only bras and grass skirts. Some women have beauty scars placed on their chests and arms. During ceremonies, both men and women decorate their bodies with paints and dyes made from natural materials such as mud and ochre.[Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Some Asmat braid their hair into deadlocks and decorate them with shredded sago palm leaves. Black paint drawn around the eyes used to show that a man had participated in a killing party. Light bulbs that floated ashore from passing freighters used to be worn as pendants. Daggers are made from shin bone of cassowaries.

For important ceremonies- and war-making parties the Asmat decorate their bodies with lime and sago flour and put cockatoo and bird of paradise feathers in their hair and shells, feathers or pig tusks through their nose. Marsupial skin headdresses and carved ceremonial shields are also displayed. These are pained with black paint made from ash and red dye squeezed from berries. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

Some Asmat still wear long curly-cue nose rings. Cassowary quills are used to piece the nose. The most prestigious nose ornament is one fashioned from a human bone. Nosepieces are intended to give the wearer an appearance of a wild boar. Carved one-piece nosepieces sometimes are worn so they come sideways out of both nostrils. Asmat sometimes pierce their noses in several places. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972 =]

Asmat Festivals and Initiations

Villages hold major rituals on a two- to four-year cycle. In the past, ritual warfare—along with the activities that preceded and followed each battle—was viewed as a vital expression of the Asmat cosmology of dualism, reciprocity, and balance. Feasting, dancing, the carving of artworks, and long song cycles continue to reflect these values. Epic song-poems praising mythological, legendary, and historical heroes can last several days, while initiation rites, papis ceremonies, adult adoptions, and the construction of men’s houses are all marked by formal celebrations. [Source: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditionally, Asmat communities observed elaborate cycles of ceremonial feasting throughout the year. Feasts honoring the dead remain especially important. Other major occasions included the opening of a new men’s house, the dedication of tall ancestor poles (bis), the launch of large fleets of war canoes, and ceremonies celebrating masks or shields. In earlier times, many of these events centered on male activities associated with raiding and headhunting. Christian missionary influence has introduced new religious practices, and many Asmat now identify as Christian and observe major Christian holidays alongside traditional celebrations.

Before colonial contact, male initiation was one of the most significant rites of passage. Initiates were once presented with a severed head, believed to contain the spiritual power of a fallen warrior, which they were meant to absorb through contemplation. After a prolonged fast, the initiates would travel by canoe to the sea, where their sponsors thrust them into the water, symbolically killing them so they could be reborn as warriors. Although such rites no longer involve decapitation, the value placed on male prowess remains strong in Asmat society.

Asmat Spirit Canoe Ceremony

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Once all the images on an Asmat spirit canoe (wuramon) are carved and painted, the vessel, further decorated with leaves and cassowary feathers, is ready to make its appearance. Carried by the men from the interior to the entrance of the men's house, the wuramon enters the world tentatively: the prow figure is made to peer cautiously through the door and to withdraw several times before the canoe emerges fully into the sun. After a brief foray to the nearby river and other locations, the wuramon is placed on the open porch of the emak cem (men’s) house. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Following some additional rites, the young boys within the emak cem emerge one by one and crawl across the spirit canoe on their bellies, passing over either the okom or the turtle image. As each crosses the vessel he is transformed from a boy to a man. He is then seized by a man standing on the opposite side who, using a sharp mussel shell, cuts designs into the boy's body that will heal into the permanent scarification patterns that mark him as an adult. After the rites, the emak cem house, soul canoe, and other ritual paraphernalia, their purpose fulfilled, are abandoned to slowly decay. Having largely ceased by the 1950s, the celebration of emak cem and the creation of wuramon were revived in the 1970s and continue to be practiced today.

Bis Pole Feasts

Bis poles are regarded as totemic. feet. To celebrate the carving of new one the Asmat hold feasts in which people stuff themselves with beetle larvae. Traditionally a bis pole was raised for each enemy that had been killed, beheaded and eaten. The bis poles were anointed with the blood of the victim which allowed his spirit to be released.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Bis poles are carved and erected as the focal points of a memorial feast, called bis mbu or bis pokumbui, held to commemorate and liberate the spirits of individuals who have recently died. The specific details of the bis feast and display of the poles vary from community to community. Each stage in the preparation of the feast and the carving of the poles is accompanied by ceremonial protocols, and the entire sequence of ceremonies often requires six or seven months to complete. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

In Asmat cosmology, no person 's demise, other than that of infants and the extremely aged, was considered natural or accidental. Rather, all deaths were deemed to result from the actions of enemies, either through overt physical violence or malevolent magic. Each death within the community created a supernatural imbalance, which could be corrected only by the death of an enemy. The spirits of the dead lingered within the community, often causing trouble or illness, until their deaths were avenged. When a number of deaths had taken place, or if the village was suddenly beset with sickness or misfortune, the male elders would gather and decide it was time to correct the situation through staging the bis feast, which in the past was held in conjunction with a head-hunting raid.

Today a bis feast may be mounted to alleviate a particular crisis, such as a scarcity of food, or in connection with male initiation. The focus of the bis feast is the carving of the poles, which is often undertaken in several distinct stages. The trees for the poles are approached, felled, and brought triumphantly into the village as if they were enemy victims.

Once there, the trees are typically laid in front of the men's house (yeu) and roughly shaped before being transported to a specially built annex of the yeu, where they are carved by the men in secrecy under the supervision of one or more wow ipits (master carvers). Each bis pole is carved from a single piece of wood. To accomplish this, carvers select trees whose trunks are supported by planklike buttress roots. In order to create the distinctive winglike projection of the bis, all but one of the buttress roots are removed. After carving, the tree is inverted and the single remaining root becomes the winglike projection (cemen) that extends from the top of the pole. Asmat artists describe the bis as having three components: the main section of the pole with the carved figures (bis anakat), the winglike projection (cemen), and the lower section of the pole (ci and bino).

Once the poles have been completed, they are brought out of seclusion and erected on a scaffold in front of the yeu. Here the entire community gathers to dance in honor of the ancestors represented on the poles. 24 In the past, warriors also strutted about, boasting of their prowess and assuring the dead that they would soon be avenged and, hence, that it was appropriate for their spirits to cease lingering within the community and to depart for safan.

At the conclusion of the festivities the poles are taken down and transported to the groves of sago palms, on which the Asmat rely for food. Laying the poles within the groves, the men call out to the dead, saying, "We have brought you here, but do not stay here. Go instead to safan."26 Afterward, the poles are ritually destroyed or left to rot in the grove, their supernatural power slowly seeping into the soil, strengthening the palms and ensuring an abundant harvest of sago.

Asmat Body Mask Feasts

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Every few years, after several people have died within a village, the male elders gather and decide to hold a mask feast. Masks are prepared in secret within the confines of the men’s ceremonial house (yeu) and can take up to four to five months to complete. The maker of the body mask is hosted by the sponsor who accommodates him with food and drink while the mask is begin prepared. When all masks have been readied, the feast ceremony (jipae) can begin. [Source: Evelyn A. J. Hall and John A. Friede, Associate Curator Oceanic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Great importance is attached to the role of the mask wearer – not only does he play the part of the deceased, he also takes on the dead person’s responsibilities including the care of any children now orphaned as a result of his demise. The climax of the ceremonies involves the emergence of the masks from the forest that surrounds the village. The first to emerge is a conical basketry mask, which in some areas represents Mbanma, an orphan of legendary status who appears as a comic prelude. He capers about humorously whilst being pelted by the children with palm leaves and husks. The next day he accompanies the formal arrival of the dead, a group of elaborately woven fiber masks such as this one, who emerge from the forest at the edge of the village.

Each mask represents a specific ancestor whose name it bears and is typically worn by a close relative of deceased. The group of masks can number between six and twenty in a single feast ceremony. They are fondly greeted by their relatives and tour the village where they are presented with food and hospitality. They proceed eventually to the men’s house (yeu) where all dance together, the living and the dead mingling in a lively engagement which continues into the night. The following morning the dead, their spirits (appeased by the feast and entertainment they have received, or frightened at the prospect of challenges that will be made to them if they do not move on) disappear into the forest to make their journey onwards to safan where they will be transformed into ancestral beings.

At the conclusion of the dance rites, the costumes are disassembled. Leaf skirts and fringes are burned but the fiber body masks, now imbued with the power of the ancestors, are often kept in the men’s ceremonial house and can be reused in future ceremonies. They may also be placed at the base of a banyan tree or sago palm where they slowly decay, their fertile powers working their way into the forest undergrowth to invigorate the growth of the next generation of sacred trees.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Geographic,, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Encyclopedia.com, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025