ASMAT

The Asmat is a group of former cannibals and headhunters that live along the remote southwest coast of Papua. Also known as the Asmat-wo and Samot, they are a hunting, fishing and gathering people famed for their elaborate woodcarving. They hunted heads up until perhaps the 1980s and only recently switched from stone and bone tools to metal ones. Modern civilization did not touch them until recently. Asmat in local languages means "tree people" or “right man”. The Asmat call themselves “asmat-ow” (“real people”). [Source: Peter and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Oceania “edited by Terence Hays, (G.K. Hall & Company, 1996) ~]

The Asmat (pronounced AWZ-mot) have been described as a wood-age culture. They traditionally have not used stone tools, simply because stones are hard to find where they live. Up until white missionaries introduced steel fishing hooks, knives and axes, the only metal or stone items they had were obtained by trading with highland tribes, and these items were so precious that they were usually reserved for ceremonial purposes. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

The Asmat Papua are of Papuan genetic heritage. They are muscular and tall by New Guinea standards. They average 1.67 meters (five feet six) inches tall. The identification of the Asmat as a distinct group is partly a relic of outside intervention and classification processes dating to the pre-1963 era of Dutch occupation. The name “Asmat” most probably comes from the words As Akat, which according to the Asmat means: "the right man". Others say that that the word Asmat derives from the word Osamat meaning "man from tree". Asmat's neighbors to the west, - the Mimika, however, claim that the name is derived from their word for the tribe - "manue", meaning "man eater".

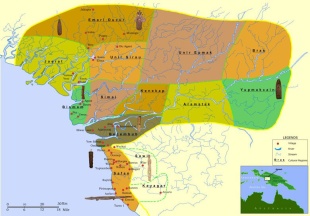

Asmat Population is estimated to be at least 70,000 , with perhaps as many as 110,000. There are five main cultural-lingustic groups of the Asmat: Central Asmat, Casuarina Coast Asmat, Yaosakor Asmat, North Asmat, and Citak. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project in the 2020s there were about 14,000 Casuarina Coast Asmat; 3,100 Yaosakor Asmat; 1,500 Northern Asmat; 14,000 Citak Asmat; and 16,000 Cental Asmat. In the 1990s, it was is estimated that there are approximately 50,000. At that time the population growth rate among the Asmat was estimated at around 1 percent. There was little migration into and out of the area where the Asmat live.

Asmat Language has 17 tenses and belongs to the Asmat-Kamoro Family of the Non-Austronesian or Papuan languages. There are around 70 different language families within the non-Austronesian grouping, and their internal relationships to each other is still unclear. The Asmat-Kamoro family has fairly large number of speakers for a Papuan language. Five dialects are spoken. Casuarina Coast Asmat speak Casuarina Coast Asmat. The Yaosakor Asmat speak Yaosakor Asmat. Northern Asmat speak North Asmat. The Citak Asmat speak Citak. The Central Asmat speak Central Asmat. Bahasa Indonesian is spoken by many. Because of missionary involvement in the region, central Asmat now have a written form of the spoken language. A modest publishing effort in the language exists that produces children's readers and religious literature.

Books: “The Asmat of New Guinea” by Michael Rockefeller (1967); “Savage Harvest" : A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller’s Tragic Quest for Primitive Art” by Carl Hoffman (Morrow, 2014); “Embodied Spirits: Ritual Carvings of the Asmat. Exhibition catalogue” by Tobias Schneebaum, Peabody Museum, 1990; “Asmat Art: Woodcarvings of Southwest New Guinea” edited by Dirk Smidt (1993)

RELATED ARTICLES:

ASMAT LIFE: SOCIETY, MARRIAGE, FOOD, VILLAGES, WORK factsanddetails.com

ASMAT CULTURE: MUSIC, FOLKLORE, CEREMONIES, BODY ADORNMENT factsanddetails.com

ASMAT ART: BIS POLES, SPIRIT CANOES, BODY MASKS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI PEOPLE: HISTORY, CANNIBALISM, CONTACT WITH WESTERNERS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI LIFE AND SOCIETY: RELIGION, FOOD AND TREEHOUSES factsanddetails.com

ASMAT AND KOROWAI COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SOUTHERN LOWLANDS OF PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

MARIND PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (SOUTHWEST NEW GUINEA, INDONESIA) factsanddetails.com

KIMAM PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

Where The Asmat Live

The Asmat live within the Indonesian province of South Papua (previously part of Papua, Irian Jaya or West Irian) in the south-central alluvial swamps of West New Guinea. They are scattered in 100 villages across a 27,000 square kilometer (10,425 square mile) area in one of the worlds' largest and most remote alluvial mangrove swamps — a wet, flat, and marshy place, punctuated by stands of sago palms and patches of tropical rain forest. Many of the rivers near the coast rise and fall with the tides.

The Asmat region is located at approximately 6° S and 138° E, on the periphery of the monsoon region. The most prevalent winds blow from November through April. December is the hottest month and June is the coolest. Rainfall regularly exceeds 450 centimeters (177 inches) per year. Numerous streams and tributaries that overflow their banks in the rainy season provide the primary means of transportation for the Asmat. [Source: Library of Congress]

The area where the Asmat live encompasses some the last unexplored regions of the world. The land is covered with bog forests and mangrove and is serrated by many meandering rivers that empty into the Arafura Sea. The tides submerge an area 100 miles inland. During high tide in the rainy season, sea water penetrates some two kilometers inland and flows back out to two kilometers to sea at low tide. During low tide the plains are muddy and impassable. Here is the habitat of crocodiles, gray nurse sharks, sea snakes, fresh water dolphins, shrimp, and crabs, while living along the banks are huge lizards. The forests contain palms, ironwood, merak wood and mangroves and are home to the crown pigeons, hornbills and cockatoos. There are grass meadows and orchids. The Asmat have share the region with the Marind-Anim and the Mimika tribes. [Source: Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia]

Carl Hoffman wrote in “Savage Harvest”:“Asmat is, in its way, a perfect place. Everything you could possibly need is here. It’s teeming with shrimp and crabs and fish and clams. In the jungle there are wild pig, the furry, opossumlike cuscus, and the ostrichlike cassowary. And sago palm, whose pith can be pounded into a white starch and which hosts the larvae of the Capricorn beetle, both key sources of nutrition. The rivers are navigable highways. Crocodiles 15 feet long prowl their banks, and jet-black iguanas sun on uprooted trees. There are flocks of brilliant red-and-green parrots. Hornbills with five-inch beaks and blue necks. [Source: Carl Hoffman, Smithsonian Magazine, March 2014]

Until the 1960s, “there were no wheels here. No steel or iron, not even any paper. There’s still not a single road or automobile. In its 10,000 square miles, there is but one airstrip, and outside of the main “city” of Agats, there isn’t a single cell tower. Here it’s hard to know where the water begins and the land ends, as the Arafura Sea’s 15-foot tides inundate the coast of southwest New Guinea, an invisible swelling that daily slides into this flat swamp and pushes hard against great outflowing rivers. It is a world of satiny, knee-deep mud and mangrove swamps stretching inland, a great hydroponic terrarium...We were crossing the mouth of the Betsj River, a turbulent place of incoming tide and outrushing water, when the waves slammed and our 30-foot longboat rolled. “

See Separate Article: ASMAT AND KOROWAI COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

Asmat History

The Asmat region was explored from the 16th to the 19th centuries by the Netherlands and Britain but the remoteness and lack of resources essentially cut the region off from colonization. The first contact by Europeans was made by the Dutch trader, Jan Carstens, in 1623. Captain Cook arrived in the area in 1770. Occasional contacts were made over the next 50 years, The Dutch government didn’t formally set up a post in the Asmat region until 1938. The original Dutch post, Agays, is now the Asmat’s main trading and mission town and administrative center. [Source: Peter and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Oceania “edited by Terence Hays, (G.K. Hall & Company, 1996)]

During World War II, the Asmat region was located on the border between the Allied-controlled territory of Papua and the Japanese-occupied region of West New Guinea. Skirmishes occurred between the Japanese and the Asmat people during this time. Permanent contact has been maintained since the early 1950s and over time contacts with the West steadily increased, with one byproduct being a decline in traditional Asmat warfare and cannibalistic practices. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Missionaries arrived relatively late in the Asmat region. A Catholic mission began its work there only in 1958, but the pace of change in this once remote region greatly increased after the 1960s. Beginning in the early 1990s, many Asmat enrolled their children in Indonesian schools, and many converted to Christianity. [Source: Library of Congress]

Disappearance of Michael Rockefeller

One of the most famous missing person cases is the 1961 disappearance of 23-year-old Michael Rockefeller, the heir to the Rockefeller oil and U.S, Steel fortune and the son of Nelson Rockefeller, governor of New York and the U.S. vice president during the Ford administration. After graduating from Harvard with a degree in ethnology, the twenty-two-year-old Michael went on an expedition to the Asmat area of New Guinea, where he traded tobacco and steel fishing hooks for carved Asmat bis-poles to add to the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

Rockefeller disappeared on his second expedition to New Guinea. One of the goals of the expedition to the Asmat region was to purchase as many woodcarvings as possible. On his first visit Michael had been deeply impressed by the Asmat sculptures, and planned to display these at an exhibition in the United States. Today the Metropolitan Museum has an outstanding collection of Asmat art, the majority of which was collected in 1961 by Michael C. Rockefeller. A group of 17 poles from the village of Otjanep was delivered to the museum after his disappearance.

Michael Rockefeller was last seen on November 16, 1961 in a jerry-rigged catamaran bound for the village of Otjaneps. He had left the town of Agats with two mission boys and the Dutch anthropologist Renee Wassing when the boat’s 18-horsepower motor conked out in the mouth of the Sirets river. The two boys immediately started swimming for shoreline to get help and Rockefeller and Davis spent the night on the boat as it drifted out into the Arafura Sea. The next morning Rockefeller could still see the shore. He tied his steel rimmed glasses around his neck and attached himself to empty oil cans for buoyancy. His last words were "I think I can make it." ♢

Rockefeller was never seen again. The Dutch navy, various missionary boats, the Australian Air Force and an American aircraft carrier participated in the search. Nelson Rockefeller and Michael's twin sister Mary arrived in a chartered plane and hired 12 Neptune aircraft to search the sea and paid the Asmat large amounts of black tobacco in return for participating in search parties. The search lasted for 10 days before it was abandoned. Rockefeller was formally declared dead in 1964, presumably of drowning. ♢

Book: “Savage Harvest: A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller’s Tragic Quest for Primitive Art” by Carl Hoffman (Morrow, 2014). The book is excerpted in “What Really Happened to Michael Rockefeller” by Carl Hoffman, Smithsonian Magazine

Asmat and the Disappearance of Michael Rockefeller

The Lawrence and Lorne Blair suggest that Rockefeller was either eaten by sharks, drowned or was eaten by Asmat headhunters. To back up the last hypothesis they theorize he might have been killed in revenge for the murder of four Asmat warleaders by a Dutch government patrol in 1958. They also point out that it seems likely Rockefeller made it to land because it is possible to touch the sea bottom three kilometers from shore and wade in from a kilometers and half out. Locals say they are few sharks in the water and the main thing they worry about is stepping on a stingray. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York ♢]

An elder war leader in Otjanep told the Blairs that after returning from fishing some of his friends found Rockefeller laying in the mud, breathing heavily. Relatives of the friends had been killed by the Dutch and they speared Rockefeller out of revenge and then dragged his body back to the village where his head was cut off with a bamboo knife. The cuts were cleaned out and the body was thrown on a fire. The meat was divided among the people of the village and the most important men ate the brains. ♢

Rockefeller’s “art” collecting may have contributed to his possible murder. In a review of the book “Savage Harvest” by Carl Hoffman, Bill Gifford wrote in the Washington Post: Rockefeller had no idea of the significance of his actions. Far from mere aesthetic objects, the artifacts he sought were spiritually alive, in the Asmat consciousness. “For the Western collector, the Asmat shield is a thing of beauty,” Hoffman writes; “for the Asmat, it is a thing of supernatural power. An Asmat might look at a shield and drop with fear.” [Source:Bill Gifford, Washington Post, March 21, 2014]

“Rockefeller was paying for these items with trinkets. The funerary bisj poles, which he acquired for the sum of a lump of tobacco and an axe, each, were even more significant, essential for guiding the dead into the next world. “He had no understanding that by trading in bisj poles he was trading in the souls of men, souls that could make you sick, that could kill you.” In the end, Hoffman concludes that Rockefeller had unwittingly stepped into a situation that was already tense and unbalanced, in the aftermath of the Dutch massacre and inter-village violence. His presence — and his money — destabilized it even further. The only way it could be brought back into harmony, in the Asmat view, was via his death.

Asmat Religion

Many Asmat have converted to Christianity, although a large number continue to practice the religion of their ancestors. For example, many believe that all deaths—except those of the very old and very young—come about through acts of malevolence, either by magic or actual physical force. Ancestral spirits demand vengeance for these deaths. The ancestors to whom they feel obligated are represented in shields, in large, spectacular wood carvings of canoes, and in ancestor poles consisting of human figurines. Until the late 1980s, the preferred way for a young man to fulfill his obligations to his kin and his ancestors and prove his sexual prowess was to take the head of an enemy and offer the body for cannibalistic consumption by other members of the village.[Source: Library of Congress]

The Asmat have traditionally been animists who believed in a pantheon of spirits that dwelled in trees, rivers or natural objects or were spirits of deceased ancestors. The goal of religion was to bring about harmony and balance with the cosmos. This was achieved through a variety rituals and practices interwoven with daily life that traditionally included things like woodcarving, warfare and headhunting. The spirits of ancestors are believed to be the cause of many illnesses and some rituals are meant to appease them. Although Islam is the main religion of Indonesia, it not practiced much among the Asmat. [Source: Peter and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Oceania “edited by Terence Hays, (G.K. Hall & Company, 1996) ~]

Asmat spirituality is a complex world of spirits, animals, ancestors and symbols that must be kept in balance. Religious practitioners include sorcerers and shaman, whose primary duties are to mediate between the human and spiritual world, often in the form of healing and exorcisms. To become a shaman requires a long apprenticeship. Clan leaders preside over rituals and ceremonies such as adult adoption, initiation and the construction of men’s houses. Asmat rituals have traditionally been performed in accordance with a two- or four-year cycle and included dancing, epic poem singing and woodcarving. Revenge warfare and headhunting raids were often performed in accordance with the ritual calendar. ~

Carl Hoffman wrote in “Savage Harvest”: The Asmat live in an “isolated universe of trees, ocean, river and swamp constituted their whole experience. They were pure subsistence hunter-gatherers who lived in a world of spirits — spirits in the rattan and in the mangrove and sago trees, in the whirlpools, in their own fingers and noses. Every villager could see them, talk to them. There was their world, and there was the kingdom of the ancestors across the seas, known as Safan, and an in-between world, and all were equally real. No death just happened; even sickness came at the hand of the spirits because the spirits of the dead person were jealous of the living and wanted to linger and cause mischief. The Asmat lived in a dualistic world of extremes, of life and death, where one balanced the other. Only through elaborate sacred feasts and ceremonies and reciprocal violence could sickness and death be kept in check by appeasing and chasing those ancestors back to Safan, back to the land beyond the sea. [Source: Carl Hoffman, Smithsonian Magazine, March 2014]

Asmat Creation Myth

In the beginning, according to the Asmat creation myth, a corpse of a man floating in the sea was brought to life by a great bird. In a previous life the man had seduced his brother's wife and was banished from his community and drowned when his boat capsized during his escape. On returning to life he floated to the land where the Asmat live today. But there was on one there and he grew bored. He tried bring to life some statues he carved but no luck, finally the spirit told him to go into the jungle to seek out the "tree woman."

The man was told to chop off the tree woman's head and return it to village where it would bring the statues he made to life. The man did what he was told. The spirit was right and soon the statues were dancing around to his delight. Then, one day a crocodile showed up and it and the man engaged in a horrible battle. The man eventually emerged the winner but he was so angry he chopped the crocodile in three pieces: one he hurled so far it lost its color. This produced the white race. Another was tossed a little less hard so it lost only part of its color. This produced men with brown skin. The third was left where it was giving rise to black men.

The Asmat equate a human with a tree. The legs are the roots, the torso is the trunk, the branches, arms, and the head, fruit. In the old days in some parts of the Asmat world a freshly severed head—the fruit—was needed for initiation rites in which a boy became a man by placing the head between his thighs to draw its power. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972 ]

Asmat and Christianity

Many Asmat have converted to Christianity. There has been a great effort to adapt Christianity to the needs of the Asmat. One missionary told the journalist Thomas O'Neill, "We can stretch our minds as far as possible and still we can never see the world as the Asmat do." In an effort to help the Asmat "find God in the natural world," Father Vince Cole wears and tooth necklace and fur headband over his red shirt and cut-off blue jeans.[Source: Thomas O'Neill, National Geographic, February, 1996 ☼]

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the number of Christians: 1) among the Casuarina Coast Asmat is 60 percent, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent; 2) among the Yaosakor Asmat is 68 percent, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent; 3) among the Northern Asmat is 80 percent, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent; 4) among the Citak Asmat is 60 percent, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent; and 5) among the Central Asmat is 80 percent, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being five to 10 percent;

Many of the Catholic missionaries in Papua belong to the Crosiers, a small order based in St. Paul, Minnesota that replaced Dutch priests in the Asmat region in 1958. "Inspired by the reforms of the Second Vatican Council in the mid-1960s," O'Neill wrote, "they saw themselves not as authority figures but as counselors who, in their own way, would go native to help the Asmat hold on to home and traditions." Attempting to rebuild the Asmat culture, which was nearly destroyed in the 1960s by the Indonesian government, which tore down men's house, outlawed feasts and destroyed sacred objects, the Crosiers incorporated Asmat rituals into their Catholic services. They also acted as mediators in clan conflicts and as intermediary between the Asmat and the Indonesian government. ☼

Some Catholic churches have been modeled after the traditional men's house with fire pits, ancestor poles and altars made from huge tree trunks. Christ is depicted with a crown of feathers. Worshipers at one church are called to prayer with a bell made from an old brake drum. At prayer meetings held at the traditional men's house men come with painted bodies, egret feathers stuck in their headbands, and daggers made from cassowary shinbones. The worshipers drum, dance, pass around roasted sago as a sign of sharing, and read passages from the a Bible translated into the Asmat language. ☼

Describing how Asmats beliefs have been incorporated into Catholicism an anthropologist told O'Neill, "The Asmat believe that when they killed and ate a person, they became that person and absorbed his skills. This is similar, of course, to the Catholic belief that we eat the body of Christ to become Christ. So I say, 'Look you don't have to go out and kill. You now have Christ'...What are Catholics after all, but ritualist cannibals?" The Asmat have also done their bit to adapt to Christian Western culture. In the village of Agats they are forbidden from appearing naked. Some worked for several weeks to earn money for shorts. ☼

Asmat Funerals

Asmat funeral ceremonies feature ceremonial shields which represent the revenge of the dead, ancestor poles (“bis”) and ancestor figures (“kawa”). There is often intense grieving and physical expressions of loss. To express their grief over the loss of a husband Asmat women traditionally rolled in muddy patches beside their house or on a riverbank. The ritual was intended not only as an expression of grief but also a way to mask the woman's scent from his ghost. Other mourners cover their head with read clay and stab the earth with bone daggers. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972 =]

Sometimes the Asmat begin mourning the dead before they are dead. A missionary told journalist Malcolm Kirk about a man was dying when the villagers rushed into his house to wail over him and "suffocated the poor fellow." Another time a woman collapsed in front of her house. Her family gather around inside the house expressing their grief and received a terrible shock when the "dead" woman walked in demanding to know what was going on. Apparently she only fainted. =

The purpose of an Asmat funeral is to placate the spirits of the dead so they don’t bother the living. Those successfully placated enter “safon”, “the other side.” The bodies of Asmat dead used to be wrapped in pandanus leaves placed on platforms to rot after the head had been removed and was worn as pendant or used as a pillow. Missionaries have encouraged Asmat villagers to bury their dead with their heads intact. =

Asmat Headhunting and Cannibalism

Until the 1950s, warfare, headhunting, and cannibalism were constant features of Asmat social life. The people would build their houses along river bends so that an enemy attack could be seen in advance. Many Asmat believe that all deaths—except those of the very old and very young—come about through acts of malevolence, either by magic or actual physical force. Ancestral spirits demand vengeance for these deaths. The ancestors to whom they feel obligated are represented in shields, in large, spectacular wood carvings of canoes, and in ancestor poles consisting of human figurines. Until the late 1980s, the preferred way for a young man to fulfill his obligations to his kin and his ancestors and prove his sexual prowess was to take the head of an enemy and offer the body for cannibalistic consumption by other members of the village.[Source: Library of Congress]

The Asmat have traditionally practiced headhunting, cannibalism as part of heir ritualized warfare scheme which usually involved revenge rectification of cosmic or clan imbalances. The heads from captured enemies were baked and skinned; a hole was cut in the skull and the brain was scraped out and eaten. The lower jaws was ripped off and worn as a pendant advertising prowess in war, and the skull was used as a pillow. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972]

Officially headhunting ended the Indonesian part of New Guinea in the 1960s. But it still seemed to be going on in the 1970s and who knows perhaps it goes on from time to time even now in remote areas. Some anthropologists have said prohibition of clan warfare and headhunting has left a huge void in Asmat culture that the modern world has yet to replace. =

Asmat Headhunting Culture

The Asmat traditionally held a deep fear of the spirits of the dead. They believed that, except in the case of infants or the very old, death was never accidental but caused by a hostile external force. Ancestral spirits—considered powerful and influential—were thought to demand vengeance for such wrongful deaths, requiring warriors to kill and decapitate an enemy and present the body for communal cannibalistic consumption. Headhunting, along with the male activities connected to it, formed the core of many Asmat rituals and ceremonies. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Many Asmat myths relate to their head-hunting tradition. In their origin story, two brothers were the first inhabitants of Asmat land. The elder persuaded the younger to cut off his head, after which the severed head instructed him in the practice of headhunting, the preparation of trophy heads, and their use in male initiation rituals. The younger brother also inherited the elder’s name—a pattern echoed in the tradition of an Asmat warrior taking the name of the person he has decapitated. The number of names a man carries marks the number of heads he has taken. Reflecting the spiritual power attributed to the dead, the skulls of relatives were also kept as protective talismans against malevolent spirits.

Asmat believe they are related to praying mantises which also eat their own kind. Trophy skulls, bone daggers, stone clubs are all associated with headhunting. As a symbol of the their headhunting skills men often wear bamboo and cassowary-quill pendants decorated with human vertebrae. Women sometimes borrow the pendants during feasts and wear them with dog-tooth necklaces and possum fur bonnets. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972 =]

Asmat Revenge Wars

The Asmat have traditionally believed that only the very young and very old die from natural causes. Everybody else died as a result of black magic or tribal fighting. Therefore almost every death needs to be avenged. In the old days this concept resulted in headhunting raids and revenge wars. These day the power of the dead is still taken very seriously but is dealt with ceremonial rituals but “avenging” still may occur.

Asmat warfare was traditionally in the form of raids, ambushes and skirmishes. Head hunting raids were usually organized to avenge the killing of a member of the raider’s tribe. Before the raid began the men painted themselves and decorated their canoes while women prepared a victory feast and exhorted their men to fight bravely. One missionary told O'Neill, "If you don't fight, you can be branded a coward, a traitor. The young people grow up hearing their leaders talk about the great wars. Then they go out and fight too." [Source: Thomas O'Neill, National Geographic, February, 1996 ☼]

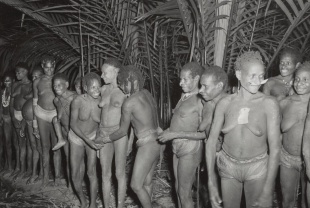

Another way for one tribe to make peace with another is for a chief in one tribe to give a child to another, often to make amends for a child killed in a previous raid. To ease tensions sometimes neighboring villages adopt members of each other's tribe. During the “adoption” "children" paint their faces with ocher and cover their heads with palm leaves. Men of the other tribe lay naked and face down and their women stand above them. The "children" then climb over the men's bodies and through the women's legs in an act meant to symbolize coming through the womb. The woman moan as if they are in labor and the "children" keep their eyes closed until they have emerged. When a child is through the woman’s legs the “father” announces the successful birth. The "children" continue playing their roll for several more days, acting childish and learning how to fish and hunt. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972 =]

Asmat Raiding Parties and Revenge Wars

An Asmat raiding party typically took off in canoes and parked them a couple of river bends before the village they planned to attack. One of the chiefs got out to scout a good route. The raiding party then broke into two groups: one heading through the forest and other advancing in canoes. When groups were in position a handful of lime was thrown into the air signaling the raid to begin. Surprise was important. The idea was to kill everybody before they had a chance to get their weapons. As many as forty or fifty people were killed in some raids, including women and children. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972 =]

While the bodies of the dead were dragged to trenches for burial the headhunters sang:"We have killed a man, we have killed a man, we are happy." Dragging the bodies through the trenches the warriors shouted, "There's no need for you to attack us again. We've revenged our dead now, so let's live in peace." The heads were then cut off with bamboo knives and carried home. Once in the villages the warriors went into their ceremonial house and displayed each head and related the story of how it was captured. =

Describing the aftermath of a revenge war in the 1980s, Lorne Blair wrote: "A wailing crowd on the bank surged around the fallen figure...At their feet lay a teenage boy—the second corpse I'd seen in fifteen minutes. His head had been partly severed by an ax blow to the back of the neck. He had joined the raid...and been killed with the villager’s sole metal axe...His mother was violently breaking up his shield and weapons, and together with her relatives and friends was screaming and moaning and rolling in the mud. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York ♢]

Journalist Malcolm Kirk landed at a village in the Asmat area in the 1970s. The atmosphere he said was disturbing. The town was unnaturally quiet and the men who greeted them were armed with bows and arrows. His guide told him that they had better get out of there, "I'll explain why later." When they were safely around a bend in their boat the guide said, "We walked right into a head hunting raid. Everyone we saw was from another village. The [villagers] heard them coming and fled.” Kirk then went to another village, called To, and traded some tobacco and fishhooks for some bone and crocodile jaw daggers. When the went back to their boat their guide told them that 15 bowmen watched them from the jungle ready to kill on signal. But why? "The To people had recently gone head hunting and killed five people. They thought we might have come to punish them," the guide said.[Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972]

The Indonesian government no longer allows revenge killing and the consumption of human brains. To end Asmat clan warfare, the government banned Asmat festivals and burned their carvings. Attacks, ambushes and skirmishes still occur from time to time. Missionaries complain that if the Asmat were left to their own devises they would spend all their time drumming, dancing and plotting wars.

Revenge War and Dutch Massacre on the Eve of Michael Rockefeller’s Disappearance

Carl Hoffman wrote in “Savage Harvest”:“A few months after Nelson Rockefeller opened the Museum of Primitive Art, Otsjanep and a nearby village, Omadesep, engaged in a mutual massacre. They were powerful villages, each more than a thousand strong, on parallel rivers only a few hours paddle apart, and they were enemies — in fact, they had been tricking and killing each other for years. But they were also connected, as even antagonistic Asmat villages usually are, by marriage and death, since the killer and victim became the same person. [Source: Carl Hoffman, Smithsonian Magazine, March 2014]

“In September 1957, the leader of one of Omadesep’s jeus convinced six men from Otsjanep to accompany a flotilla of warriors down the coast in pursuit of dogs’ teeth, objects of symbolic and monetary value to the Asmat. In a tangled story of violence, the men from Omadesep turned on their traveling companions from Otsjanep, killing all but one. The survivor crawled home through miles of jungle to alert his fellow warriors, who then counterattacked. Of the 124 men who had set out, only 11 made it home alive.

“A murder here, a murder there could be overlooked, but for Max Lepré, the new Dutch government controller in southern Asmat, such mayhem was too much. A man whose family had been colonists in Indonesia for hundreds of years, who had been imprisoned by the Japanese and then the Indonesians after World War II, Lepré was an old-school colonial administrator determined to teach the Asmat “a lesson.”

On January 18, 1958, he led a force of officers to Omadesep, confiscated as many weapons as they could find, and burned canoes and at least one jeu (bachelor’s house)...On the left a group approached — in capitulation, Lepré believed. But on the right stood a group armed with bows and arrows and spears and shields. Lepré looked left, he looked right, equally unsure what to do. Behind the houses a third group of men broke into what he described as “warrior dances.” Lepré and a force of police scrambled onto the left bank, and another force took the right. “Come out,” Lepré yelled, through interpreters, “and put down your weapons!”

“A man came out of a house bearing something in his hand, and he ran toward Lepré. Then, pandemonium: Shots rang out from all directions. Faratsjam was hit in the head, and the rear of his skull blew off. Four bullets ripped into Osom — his biceps, both armpits and his hip. Akon took shots to the midsection, Samut to the chest. Ipi’s jaw vanished in a bloody instant. The villagers would remember every detail of the bullet damage, so shocking it was to them, the violence so fast and ferocious and magical to people used to hand-to-hand combat and wounding with spear or arrow. The Asmat panicked and bolted into the jungle.

“The course of affairs is certainly regrettable,” Lepré wrote. “But on the other hand it has become clear to them that headhunting and cannibalism is not much appreciated by a government institution all but unknown to them, with which they had only incidental contact. It is highly likely that the people now understand that they would do better not to resist authorities.” In fact, it was highly unlikely that they had reached any such understanding. For the Asmat, Max Lepré’s raid was a shocking, inexplicable thing, the cosmos gone awry. They built their entire lives around appeasing and deceiving and driving away spirits, and yet now this white man who might even be a spirit himself had come to kill them for doing what they had always done. The Dutch government? It was a meaningless concept to them.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Geographic,, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Encyclopedia.com, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025