SOUTHERN PAPUA

Southern Papua is a lowland region dominated by extensive swamps, large rivers and coastal plains and borders the Arafura Sea to the south. South Papua Province is the main province. Central Papua includes some coastal areas that face southward. The region’s swampy lowlands are a a stark contrast to the mountains found further north. A network of large rivers that originate in the rainy highlands, including the Digul, Maro, Pulau, and Mapi rivers, create a vast network of waterways and wetlands.

Southern Papua is home to two main ecoregions: the Southern New Guinea freshwater swamp forests and the Southern New Guinea lowland rain forests. The Arafura Sea separates New Guinea and Australia. Wasur National Park in southern Papua covers an expansive wetland area and is known for its rich biodiversity. The climate is generally warm and humid. It is influenced by two monsoon seasons: a southeast monsoon from May to October and a northwest monsoon from December to March.

South Papua is home to rich biodiversity and diverse ecosystems. Unique wildlife includes agile wallabies, mound-building termites, and the bird of paradise.Many of the local plant and animal species are endemic to the island. Sago trees are a dominant plant in the region and are a staple food for local tribes. The swampy environment is well-suited to the robust growth of sago, even in waterlogged areas and along riverbanks.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MARIND PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (SOUTHWEST NEW GUINEA, INDONESIA) factsanddetails.com

KIMAM PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

ASMAT: HISTORY, RELIGION AND HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

ASMAT LIFE: SOCIETY, MARRIAGE, FOOD, VILLAGES, WORK factsanddetails.com

ASMAT CULTURE: MUSIC, FOLKLORE, CEREMONIES, BODY ADORNMENT factsanddetails.com

ASMAT ART: BIS POLES, SPIRIT CANOES, BODY MASKS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI PEOPLE: HISTORY, CANNIBALISM, CONTACT WITH WESTERNERS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI LIFE AND SOCIETY: RELIGION, FOOD AND TREEHOUSES factsanddetails.com

ASMAT AND KOROWAI COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

FREEPORT (GRASBERG) GOLD AND COPPER MINE IN PAPUA, INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

PROBLEMS AT THE FREEPORT MINE: VIOLENCE, POLLUTION AND BRIBES TO THE MILITARY factsanddetails.com

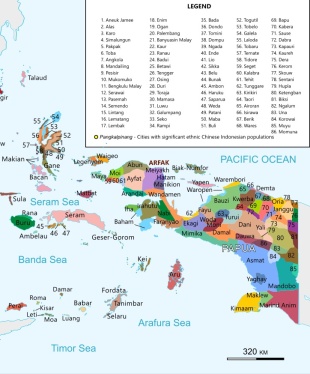

Ethnic Groups in Southern Papua

Southern Papua, Indonesia is home to numerous ethnic groups. The Asmat, Marind, Muyu, and Korowai are among the better known ones. Some are concentrated in different regencies like Merauke, Asmat, Mappi, and Boven Digoel. These groups have distinct languages and cultural characteristics, though they share a common reliance on sago and fish for sustenance in the region's swampy lowland environment.

Merauke Regency is home to Bian Marind, Kanum, Marind Dek, Marind Laut, Marori, Yab, and Yey. Asmat Regency is where the Citak, Pisa, Sawi, and Tamnim live along with the Asmat. Among the groups found in Mappi Regency are the Airo-Sumaghaghe, Awyu, Kayagar, Muyu, Siagha, Tamagario, Yaghay, and Yenimu. The Muyu also live in Boven Digoel Regency along with the Aghu and Iwur,. Other groups include Are, Kakaib, Kamindip, Kasaut, Kawiyet, Ningrum, Okpari, Yonggom, Kauwol, Kombai, Kotogut, Wambon/Mandobo, Wanggom, and Yair

Foreign contact may have begun as early as A.D. 1600, when Chinese, Indonesian, and Dutch traders entered the region from the west via Etna Bay. In the early twentieth century, under Dutch colonial rule, Ceramese Muslim traders appointed nominal local leaders (radjas) in western Mimika, spurring a brisk trade in ironware, cloth, earrings, and beads in exchange for resin, food, and slaves.

Yaqay

The Yaqay people live in the Mappi Regency of South Papua. Also known as the Yaqai, Jakai, Sohur, Mapi and Jaqai people, they have traditionally resided in the swampy lowlands north of the Mappi River. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 17,000 and around 60 percent were Christian, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent. [Source: Joshua Project]

Language: Yaqay (also spelled Yakhai, Yaqai, Jakai, Jaqai) is a Papuan language. It is also known as Mapi or Sohur. The main dialects include Oba–Miwamon, Nambiomon–Mabur, and Bapai. According to Ethnologue, Yaqay is used along the south coast of Mappi Regency, extending up the Obaa River northward to the Gandaimu area. [Source: Wikipedia]

Sexuality: According to “Growing Up Sexually": “Adolescent amorous practices consist of subtle exchanges of looking or gestural signs. Ad hoc songs address indecent and illegal sexual practices, such as the improper positionings of little girls, and the seduction of an adult female with a little boy. Marital advise is provided after marriage. Boelaars (1958, 1981 and 2001) speaks of a homosexual exchange custom: “A father can order his young son to spend the night with a certain man, who may then commit paederastie with the boy. The father receives compensation for this. When this happened regularly in the past, a fixed relationship developed between the man and the boy, similar to that between father and son (anus father, mo-ée and anus son, mo-maqmentioned). The boy could then rest assured that he could consider that man's daughter as his "sister" and that she would be assigned him as a trade sister for his future marriage. The boys begin at this age ["grand children"] following in the footsteps. adult men also wear a fiber tail, because the anus region is regarded by men as their pubic part. “Great ass” will be called names.” [Source:“Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004; Archive of Sexuality, sexarchive.info ]

Boelaars mentions the growth principle, which is officially kept secret from the female kind: “The men give the reason that homosexuality between an older man and a boy promotes the growth of the mo-maq, the scandalous boy…Homosexuality is seen as something that happens in the service of life.” Boelaars argues that the practitioners themelves consider it "immoral" (degrading) Because accusations led to inter-village quarrels. Also, the boys would have begun to refuse their participation. To end the practice, Dutch policies recommended the promotion of “family life” and desegregation of the sexes.

In his original manuscript, Boelaars notes that sexual awareness begins at around age 10. Girls are marriageable from the time breasts start to drop, which would be prevented by intermammilary scarification. On childhood: “It can happen that boys sit opposite each other and try to touch each other's genitals as a joust. One often hears, also with children, the word paradi, penis, as a expletive; Friends can laugh amongst themselves the saying joqajo-maq : which means as much as a whore's child. According to Toani van Képi, the little girl is taught from an early age that she should sit down “neatly” and should only play with “brothers” and “sisters”. However, the game only really starts when the boys are about fourteen years old and the girls have had their first menstrual period. The Jaqaj know the existence of the hymen, Umber, and they think it breaks with the first menstrual period. Dealing beforehand is severely condemned, and if charges are made against anyone on this point, the matter will be thoroughly investigated; and if the offender here is not a best suitor, he can expect heavy- handed punishment.”

Kamaro

The Kamaro live in an area of lowlands and some inland mountains on the south coast of Papua in the Mimika Regency of Central Province, particularly along the coast and rivers. Also known as the Mimika, they have traditionally lived in longhouses and migrated between upstream sago gardens and downstream fishing grounds and have some similarities with the Asmat and Kapauku. The Kamaro have rich cultural traditions, especially in wood carving and oral literature. Today, they now face the challenges from modern industrialization and an influx of outsiders from elsewhere in Indonesia.

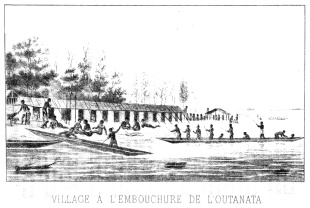

The Kamaro have no specific indigenous name for their homeland. The name Mimika comes from the Mimika River. Kamoro means “living person,” in contrast to “ghosts.” The Kamaro also refer to themselves as wènata, “real human beings,” distinguishing themselves from “not-real persons” such as the neighboring Asmat and Ekagi. The territory of the Kamaro lies between 4°–6° S and 134°59 –136°19 E, bounded by the Utakwa River to the east and the shores of Etna Bay to the west, in an area of lowland plains cut by roughly sixty swamp and mountain-fed rivers and creeks. The main urban center is Timika city. Southeast monsoon winds bring steady rains from June to mid-September, though the region’s wet and dry seasons are only weakly defined. [Source: Jan Pouwer, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Population: According to the Christian-group Joshua Project the Kamaro population in the 2020s was 14,000. There were around 10,000 of them in the 1990s and 8,600 in 1955, with some Indonesians living among their homeland territory, primarily to harvest ironwood. Indonesian migrants began settling in the Mimika area in 1962. The Kamoro language is part of the Asmat-Kamoro Family of Non-Austronesian languages. Six to eight dialects have been identified.

History: Oral traditions trace the origins of the Kamoro to conflicts over sago groves among four lowland groups east of the Utakwa River. A southwestward migration by one group set off a chain reaction, prompting other eastern groups to move westward as well. Linguistic evidence suggests a deeper prehistoric movement: Asmat (to the east of Mimika) and the distant Sentani of the north coast share a genetic linguistic relationship, pointing to a possible ancient northeast–southwest migration.

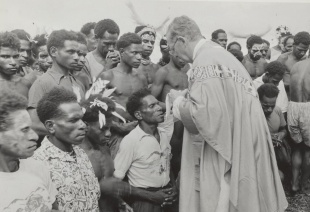

Foreign contact may have begun as early as A.D. 1600. Over time, Kamoro attitudes toward outsiders passed through several phases: initial hostility followed by cautious accommodation; enthusiasm driven by the desire for Western goods; disappointment and passive resistance to interference with their seminomadic lifestyle; and, after the Japanese occupation in World War II, a shift toward coexistence and acceptance of foreigners as a permanent presence.

Today, many Kamoro are Christians. Economic development in their homeland remains limited due to the scarcity of marketable natural resources. They retain historical memories of conflict with their neighbors, the Asmat. In the modern era, the Kamoro live in a regency that now hosts a large migrant population, bringing new economic activities as well as new challenges.

Kamaro Religion

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 65 percent of Kamaro are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent. Although Christianity has transformed many ritual practices, a major revival of traditional ceremonies occurred in the 1950s. [Source: Jan Pouwer, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Kamaro cosmological and ceremonial schemes have male and females aspects. In Kamaro cosmology, there is an upstream side of the universe oriented towards females and a downstream side oriented towards males. The Kamaro believe the original inhabitants of the earth were men who emerged from the penis and anus of a founding spirit.

Religious Practitioners have traditionally been elder men and women who hold extensive ritual knowledge and presided over ceremonies performed by their respective genders. Illnesses are treated by specialized practitioners—each disease has its own male or female healer who knows the appropriate formulas and techniques. There are no general-purpose ritual specialists.

Life-Cycle Ceremonies: are held in conjunction with birth, death and the marking of adolescence with a ceremonial nose piercing. The two principal rituals, Kaware and Emakame, are complementary, relating to each other as male to female. Considered the “mothers” of all other ceremonies, they underpin rites of passage marking birth, adolescence (notably the piercing of boys’ nostrils), and death. Kaware represents male authority over ritual knowledge, secrecy, and communication with the invisible underworld, while Emakame embodies female powers of productivity, reproduction, and erotic life.

Death: According to tradition, humans and ghosts once lived together peacefully and even intermarried. Death entered the world when humans violated the principle of reciprocity. The dead now dwell in parallel villages in the underworld, an ideal landscape of clean sand and abundant gardens rather than mud. The male culture hero who carries the sun across the sky each day descends into this underworld at night, following a path connecting its villages, and reemerges in the eastern sky each morning. In contemporary belief, God, Jesus, and Mary are also said to reside in the underworld.

After a person dies, the separation from the living unfolds over several years. The process culminates in a masquerade in which respected men and women impersonate the deceased while relatives and friends mourn, praise their life, and at last invite the spirit to depart peacefully. The soul—understood as distributed throughout the body’s moving parts—leaves the corpse, travels upstream, and then descends into the underworld through a hole beneath a tree.

Kamaro Society and Family

Kamoro social life has traditionally centered on longhouse communities, led by respected elder men. These communities, based on two forms of matrilineal descent (along female lines), were linked to neighboring longhouses for warfare, feasting, and the exchange of women. Today they often live in villages but maintain autonomy. A pervasive principle of duality shapes settlement patterns, land use, ritual, and social relations. Political authority is held by non-hereditary “great men,” whose influence depends on oratory skill and strong kin networks. Warlords, distinct from everyday leaders, led raiding parties formed through shifting alliances. [Source: Jan Pouwer, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Households consist of a nuclear family plus dependent relatives. Sister exchange is the ideal form of marriage, though bridewealth is common. Relations between bride givers and takers follow rules of avoidance and joking. Residence ideally is uxorilocal or matrilocal. Parents share childrearing duties, with older siblings helping once children are weaned. The longhouse ideal persists in temporary sago- and fishing-camp settlements. Households cooperate flexibly, often in small work groups. Inheritance of land and resources is fluid, but ritual knowledge—such as control over weather or disease—follows patrilineal rules.

Kinship is gendered and centers on sibling relationships. Men are said to have two kinds of offspring—those of their penis (their own and their brothers’ children) and those of their anus (their sisters’ children). Women ensure continuity of matrilineal descent. Kin terms emphasize horizontal, generational ties and distinguish “superior” wife givers from “inferior” wife takers, who owe significant services. Two types of matrilineal groups—vertical and horizontal—form the core membership of landholding units.

Kamaro Villages, Life and Economic Activity

Kamoro life has traditionally centered on sago production, followed by foraging, fishing, small-scale slash-and-burn gardening of tobacco, bananas, and tubers (especially upstream), and hunting. Coconut palms are grown everywhere, but cash crops are minor. Limited industrial activity—mainly timber supply to a local mill and some ironwood for export—is controlled by Indonesian merchants. Most cash income comes from migrant labor in urban centers. Traditional food production once followed ceremonial cycles, but this rhythm has been disrupted by administrative duties and church attendance. Many people now spend Monday to Saturday at sago and fishing grounds and return to the village for services. Timber brings some income, though wage work outside the district remains more significant, and trade stores are owned primarily by Chinese and Indonesian merchants.[Source: Jan Pouwer, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The largest population concentrations occur in the central and eastern regions, where villages range from 60 to 400 people. In the past, households lived in small dispersed shelters around semipermanent longhouses, and daily life still involves moving between upstream sago groves and downstream fishing grounds. Longhouse patterns are retained in temporary work camps, while mission and colonial influence introduced separate family houses in the villages.

Women take primary responsibility for sago extraction, fishing, foraging, collecting shellfish and firewood, preparing food, and managing canoes, mats, bags, and household supplies. Men make canoes, tools, weapons, and fishing and hunting gear, and they build both longhouses and village dwellings. Men also carry out most gardening and are now the principal wage laborers. Ritual life is predominantly controlled by men, though elder women retain considerable influence and knowledge. Specialist drummers, singers, and wood-carvers occupy important roles.

Kamoro material culture has traditionally been simple and suited to a seminomadic lifestyle. They produce two main canoe types: dugouts for river travel and larger seagoing canoes with high bows. Traditional trade was limited and focused on exchanging canoes for sago rights in western Kamoro, where sago is scarce. Inland communities traded tobacco to coastal groups and also obtained tobacco from highlanders in exchange for inferior iron tools.

Land Tenure reflects a flexible social structure with widely diffused authority. Boundaries are clearer along waterways—vital for canoe travel—than on land. Land cannot be alienated to outsiders, though they may be granted use-rights. Sago groves belong to sibling and cousin groups and their descendants, and access is often extended to kin and affines. Women wield significant authority: tidal creeks used for weir fishing are typically owned and controlled by sisters, female cousins, or mothers with daughters. Gardens are usually the property of older married couples, while individual trees may belong to either men or women. Because kinship is broadly defined—incorporating adoption, friendship, and various affiliative ties—actual land and creek use tends to be collective and flexible. Land disputes occur mainly between neighboring villages with adjacent territories.

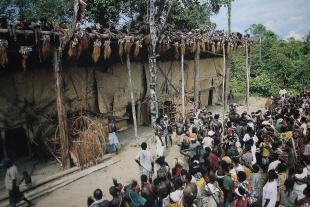

Kamaro Art and Ceremonies

The Kamoro are recognized for their distinctive, understated woodcarving tradition, which contrasts with the bolder style of their Asmat neighbors. Kamaro carvings are closely tied to ceremonial life, notably the shield-like panels representing ancestral mothers and recently deceased relatives. The most striking works are the monumental spirit poles (mbitoro), stylistically related to Asmat bis poles. Mbitoro feature highly stylized male and female figures commemorating notable individuals and are erected before ceremonial houses during nose-piercing rituals. The mbitoro motif also appears on drum handles, and many everyday objects carry carvings of hornbills, cassowaries, and other figures.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The art and culture of the Kamoro people share a number of important forms and themes with those of the Asmat, who Iie immediately to the east. These include rituals and wood carvings honoring the spirits of individuals who have recently died. Whereas Asmat sculpture is characterized by curvilinear forms and motifs, Kamoro art exhibits an energetic angularity, in which rectilinear, triangular, or zigzag-shaped elements combine to form intricate surface patterns or delicate open work compositions of highly rhythmic sophistication. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a 163.5-centimeter (64-inch) tall wood ancestor board (yamate) from the Kamaro area dated to the mid-20th century. Representing recently deceased ancestors, yamate, were created and displayed primarily as part of the emakame, ritual honoring the dead and celebrating the renewal of life. The term emakame — “house of bones" — refers to the large ceremonial house that was built for the rites. Portions of the ceremony involve dramatic reenactments of oral traditions that recounted the genesis of life from death.

Celebrating the spiritual interrelationship between life and death, the various stages of the emakame involved the display of the images of the dead, as well as the initiation of the young into the secrets of adult religious life and sexual procreation, which ensured the continuity of the ancestors through their living descendants. A pivotal event in the emakame was the revelation of the yamate boards, each of which represented a specific deceased individual, for whom it was named.

During the rites a group of yamate, concealed beneath mats, was erected by initiated men in front of the emakame house; spikelike forms that projected from the base of the boards allowed them to be inserted into the ground. When the moment came for the yamate to be displayed, another group of men staged a raucous mock fight to distract the women while the men removed the mats from the yamate. After calm was restored, the women returned and gazed upon the boards, shouting loudly in admiration.

One by one the men then identified the individuals represented by each of the yamate. In addition to the amate displayed outside the building, numerous examples were attached to the walls inside. The present work, which lacks the spikelike projection at the base, was likely intended for display in the interior of an emakame house. At the conclusion of the ceremony, the yamate, like Asmat bis poles,, were deposited in the sago-palm groves, where they slowly decayed their supernatural power (kapita) invigorating the trees. In the past yamate were carved in two basic varieties: "closed” yamate, or solid boards with designs carved in low relief, and "open" yamate, such as the present work, with images rendered as open work compositions. Although many yamate were adorned entirely with geometric patterns, the boards also frequently incorporated stylized human figures. Although the precise nature of the figures is uncertain, it seems reasonable to suggest that the were intended to represent the ancestors for whom the boards were named. The present work consists almost wholly of a single stylized human figure shown in profile. The figure's head appears at the top and its curving back forms the right margin of the board. The form of the V-shaped arm, with the hand grasping the left margin, is echoed by the leg, with its sharply bent knee. A second, inverted human head appears at the base.

Whether displayed in front of the emakame house or attached to the walls within, only one side of the yamate was typically visible. As a result the reverse side was often blank or bore designs that were only summarily carved and painted. This yamate is adorned almost identically on both sides, although the designs on the reverse lack the fine details of the side seen here. In addition to their role in the emakame rites, many openwork yamate were used on festive occasions as canoe ornaments. Since both sides of these yamate would be visible when the boards were attached to the bows of large war canoes, the two surfaces were similarly decorated. and is possible that the present work was intended solely as a canoe ornament. However, both its overall form and the differing quality of the decoration on the two sides suggest that it was a yamate that also served as a canoe-prow ornament.

Muyu

The Muyu live mainly in the interior of New Guinea in South Papua province, just south of the central mountains. The name Muyu is taken from the Muyu River, a tributary of the Kao River, itself a tributary of the Digul River. The term “Muyu” has two likely origins. One traces to the arrival of Catholic missions in 1933, when Father Petrus Hoeboer heard local residents refer to the western and eastern sections of a river as ok Mui (“Mui River”). This name, frequently repeated to the Dutch, gradually evolved into Muyu. A second explanation comes from an earlier encounter in 1909, when Dutch explorers traveling up the Digul and Kao rivers met members of the Kamindip subgroup, specifically the Muyan clan. Introducing themselves as neto muyannano (“we are Muyan people”), they provided the name that was later recorded as Muyu and applied to the wider group. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

The Muyu originally inhabited the hilly country between the central highlands and the plains of the south coast. Their territory today is bounded by Papua New Guinea to the east; the Kao and Digul rivers and Merauke Regency to the south; the Star Mountains to the north; and Boven Digoel Regency to the west. The region extends roughly 180 kilometers (110 miles) and covers about 7,860 square kilometers (3,035 square miles), with a width of 40–45 kilometers (25 to 18 miles). The Muyu language is spoken throughout the area, along with the Ninati and Metomka dialects. The landscape is generally hilly, ranging from 100 to 700 meters in elevation. The reddish-brown soils are relatively infertile, contributing to periodic food shortages and historically high mortality. There is no clear wet or dry season in the Muyu area. It rains a lot of the time. The average rainfall is between four and 6.5 meters (13 to 21 feet) per year, depending on the location in the area.

According to the Christian-group Joshua Project in Indonesia in the 2020s the South Muyi population was 2,000 and the South North population was 2,000. In 1956 the Muyu population was estimated at 12,223, with the average population density being three persons per square kilometer. In 1984, dissatisfaction with conditions in their homeland led roughly 7,000 Muyu to flee across the border into Papua New Guinea. By 1989, a few thousand had returned to Papua, with some resettling in the Merauke region on the south coast. Traditionally highly mobile, the Muyu have long migrated in search of better economic opportunities. Today, a large number continue to live in Papua New Guinea’s Western Province as refugees.

Muyu Language is comprised of dialects of Kati in the Ok Family of Papuan languages. The relationship between the Muyu language and the languages of the surrounding people is still unclear and relatively little researched.

History: The Muyu likely migrated from the central mountains to their current territory, maintaining extensive relations with neighboring groups through trade. In 1902, a Dutch Indies administration post was established on the southeast coast as the capital of the South New Guinea Division, which included Muyu lands. The first Muyu contact with outsiders probably occurred between 1907 and 1915 during Dutch military explorations of New Guinea.

Foreign relations intensified between 1914 and 1926, when Chinese, Japanese, Australian, and Indonesian hunters pursued birds of paradise in South New Guinea. Some young Muyu accompanied these hunters to other parts of the Dutch Indies and Merauke. In 1927, the Upper Digul Subdivision was established with Tanah Merah as its capital, including Muyu territory. Administrative oversight began, particularly to control frequent revenge killings.

Missionaries from the Congregation of the Sacred Heart opened a mission post at Ninati in 1933, followed by government administration in 1935, when the Muyu area became a sub-subdivision or “district.” Contact with missionaries and officials intensified, and in 1955 the Muyu became a formal subdivision headed by a controleur BB reporting to the resident of South New Guinea Division in Merauke. After Dutch New Guinea became part of Indonesia in 1963, the Muyu area was reorganized as a kecamatan, with a camat as chief under the kabupaten of Merauke, led by a bupati. Dissatisfaction with limited development, mistreatment by the military, and pressure from the OPM (Organisasi Papua Merdeka) prompted roughly 7,000 Muyu to flee to Papua New Guinea.

Muyu Religion and Culture

Most Muyu are Roman Catholics. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project 60 percent of South Muyu are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent, and 65 percent of North Muyu are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being 5 to 10 percent. Roman Catholicism was brought to Muyu region by Dutch missionaries with the help of Indonesian (Kaiese) catechists and schoolteachers, who rather than replacing traditional beliefs merged with them, creating a distinctive religious culture. Muyu culture itself is modestly artistic, featuring decorated hand drums and large shields used in combat. Songs and dances are practiced but not thoroughly documented. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Traditionally, the Muyu practiced a religion that included beliefs in supernatural beings, origin myths, religious-medical practices, and ritual ceremonies. For the central Muyu, the supernatural being Komot is most important, organizing the life of the Muyu and playing a key role in hunting. Another central myth concerns Kamberap, a primeval man from whom both the sacred and domesticated pigs originated. These myths also explain the wealth and knowledge of foreigners, who are believed to keep their methods secret. Historically, Muyu participated in cargo cults to acquire similar wealth and status, and these ideas may have influenced the 1984 migration to Papua New Guinea. Even today, spirits of ancestors—especially wealthy deceased individuals—play an active role in daily life, rewarding rule-following and punishing transgressions.

Religious Practitioners Traditional Muyu religion had no formal specialists. Muyu medicine is largely spirit-based, attributing illnesses to deceased ancestors (tawat). Diseases caused by sorcery can only be cured if the perpetrator retrieves the harmful object (mitim). Modern medicine, introduced by missionaries and the government, is available in the small hospital at Mindiptana.

Ceremonies, including sacred pig slaughters (yawarawon), boys’ initiation rites with bullroarers (mulin), and sacred flute performances (konkomok), could be conducted by any adult. Knowledge of the supernatural was passed individually from father to son or mother to daughter, and magical items could be acquired from others. Catholic religion is taught and led by catechists, schoolteachers, and priests, with most catechists and some teachers being Muyu, while priests are usually Dutch or Indonesian. The Roman Catholic Church follows its liturgical calendar, though in remote villages ceremonies may be infrequent due to limited priest visits. Traditional ceremonies for pig feasts, boys’ initiations, and certain illnesses continue alongside Catholic practices.

Funerals and Beliefs About Death: Upon death, kin are notified, and women participate in lamentations. Traditional practices included burial, drying over fire, or leaving the body to dry on a rack before eventual burial with pig fat during a feast. These measures reflected respect for the deceased and fear of their tawat, which could affect agriculture and pig-raising if angered. Ancestors were believed to live in settlements resembling those of the living, enjoying a carefree existence. Today, Christian beliefs of Heaven and Hell coexist with traditional views, and Roman Catholic funerals are performed when a catechist, teacher, or priest is available.

Muyu Society, Family and Kinship

Muyu society has traditionally been relatively egalitarian, though wealthy individuals (kayepak) held greater influence. Muyu society is organized into patrilineages based on male descent that also function as territorial units. Several lineages now share a single village. The kinship system is based on exclusive cross-cousin marriage. Social uniformity has always been weak because of dispersed settlements, flexible lineage structures, extensive trade networks, diverse marriage alliances, and the individual transmission of supernatural knowledge. Modernization has introduced a new class of educated people with higher status and access to modern wealth, but most live outside the Muyu region due to limited local economic opportunities. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

Within the tribe, authority in social and religious life is held by a chief and kayepak and tomkot (“big men”). Tomkot possess few valuables and limited mystical knowledge but hold influence within their lineages. Kayepak, by contrast, own significant wealth (tukon, including shells and other valuables) and have mastery of mystical powers. These leaders exercise authority within patrilineal kin groups, generally composed of nuclear families. Traditionally, the lineage was the highest political unit. Lineages were small and loosely organized, lacking formal chiefs. Kayepak exercised influence through their wealth and their ability to provide assistance or, in extreme cases, hire killers. No formal courts existed; order was maintained through revenge, compensation, and the threat of violence. This often produced an atmosphere of fear and caution.

The nuclear family is central to managing land, food production, settlement patterns, and the transmission of supernatural knowledge. Nuclear families form patrilineal lineages, which in turn connect to broader kin networks. Most households consisted of a nuclear or polygynous family. Sons inherited land, fishing waters, and valuable objects, with the eldest receiving slightly more. Wives and daughters inherited smaller portions. Children were raised by both parents, but after age 5–6 boys spent more time with their fathers and girls with their mothers. Independence and self-reliance were emphasized from an early age.

Marriage is structured around bride-price, which enables cross-cousin marriage and an open, asymmetrical system. Ideally, men married their mother’s brother’s daughter, while marriage to one’s father’s sister’s daughter was forbidden. Bride-price created flexibility in partner choice and reinforced long-distance trade relationships. Residence after marriage was patrilocal, with couples establishing independent households. Divorce was (and remains) rare due to bride-price obligations and Catholic influence. Polygyny has been common, especially among men who could afford multiple wives, who contributed labor to gardens and pig raising. Catholic missionaries promote monogamy, but traditional practices persist.

Land Rights were strictly individual. The entire region was divided into precisely recognized personal plots, including garden land and fishing areas, which passed from father to sons. With no written system of registration, a major modern concern is the potential failure of state authorities to recognize these traditional rights, risking land loss and conflict.

Muyu Life, Villages and Economic Activity

The Muyu subsist primarily through hunting, fishing, pig and dog husbandry, and sago production. Their traditional currency were ot (shell valuables) and mindit (dog teeth). They are slash-and-burn horticulturalists, once reliant on stone axes for clearing forest but now using iron tools. Their main crops include numerous varieties of bananas and root crops, especially yams, sweet potatoes, tobacco, and breadfruit. Sago palms, planted along waterways and in swamps, are a dietary staple for southern Muyu groups. Each wife tended her own garden. Husbands performed the heavier tasks such as felling large trees, but women carried out most clearing, planting, crop care, and pig husbandry. Attempts to introduce commercial crops such as rubber and cacao between 1960 and 1962 initially showed promise, particularly rubber, but government efforts were not sustained and the projects eventually stagnated. Pigs remain the most valued domestic animals. [Source: Pim (J. W.) Schoorl, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Before mission and government intervention, Muyu settlements were characterized by being highly dispersed. Patrilineal lineages formed small territorial units of four to sixty people, but even within these clusters houses were scattered because every adult man sought to build his home on his own individually owned land. Families often lived directly in their garden clearings. Houses—well built and raised about 10 meters above ground on cut tree trunks or tall poles—were constructed of palm wood and rattan with sago-thatch roofs, offering protection and visibility. After 1933, missions and government administrators encouraged the formation of large, nucleated villages of 150–400 inhabitants to facilitate schooling, church work, and administration. Houses in these villages were arranged neatly along roads, still built on poles but typically only one to three meters high.

The Muyu had few traditional industrial arts; even stone axes were imported through trade. They produced their own bows and arrows, drums, and, in the south, dugout canoes. Northern groups constructed rattan suspension bridges. Little new craft technology has been adopted. The Muyu maintained an extensive traditional money system using cowrie shells, which facilitated trade in pigs, pork, bows, tobacco, magic stones, ritual knowledge, ornaments, and even services such as hiring a killer. Shell money also played a key role in bride-price exchanges. By the mid-20th century, traditional currency was largely replaced by cash. A Chinese toko (trade store) opened in 1954, prompting rapid uptake of imported goods. After 1963, supplies dwindled and prices for local products—especially pork and bride-price payments—rose steeply due to inflation and scarcity.

Kimam

“Kimam” refers to the inhabitants of Yos Sudarso Island—a 102-mile-long island in Papua, Indonesia, located between 137.7–139.1°E and 7.4–8.5°S. Covering 11,743 square kilometers (4,534 square miles), it is separated from mainland New Guinea by the narrow Muli Strait. Formerly known as Frederik-Hendrik Island, it was renamed Yos Sudarso Island after Indonesia assumed administration in 1963. Other local names include Kolepom, Kimaam, and Dolak.

The population of Yos Sudarso Island in 2018 was about 11,000. In the early 1960s, it was roughly 7,000, spread across 25–30 villages—about 3.9 people per square kilometers (1.5 people per square mile). The island’s topography resembles a shallow saucer: the coastal rim is higher than the marshy interior. During the rainy season (January–May) the central basin floods and then slowly drains during the dry season, though it never fully dries. The interior supports reeds and rushes, while the coasts have wide mangrove belts. Isolated higher areas in the northeast, west, and south contain savanna grasslands and eucalyptus forest.

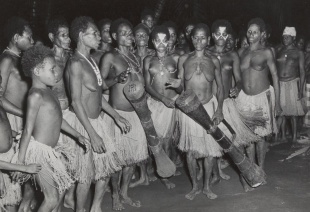

History: According to tradition, the Kimam migrated from the Digul River region on the mainland to escape headhunting raids. Dutch explorer Jan Carstensz reached the island in 1623, but sustained government and missionary presence began only in the 1930s, centered in the eastern village of Kimaam. Colonial administrators and Catholic missionaries attempted to consolidate settlements and suppress certain traditional practices. By 1960–62, bachelor-hut ceremonies and rituals involving the collection of sperm for headhunting or gardening magic had largely disappeared. Villages were required to seek government permission to perform dances linked to competitive feasting, mortuary rites, yam magic, and bachelor-hut traditions. Before Dutch pacification, inter-village headhunting occurred, though the Kimam more often suffered raids by mainland Marind-Amin and Digul River groups. Elements of Marind-Amin culture—such as dances and totemic names—occasionally diffused to the Kimam.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Geographic,, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Encyclopedia.com, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025