POLLUTION CAUSED BY THE FREEPORT MINE

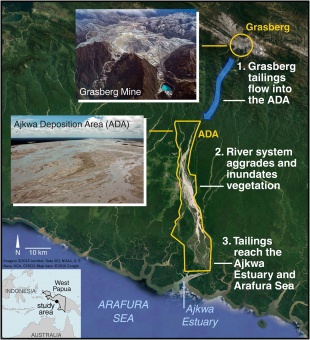

The Grasberg mine generates roughly 700,000 tonnes of tailings per day and these are discharged into the Aikwa river system, creating extensive sedimentation zones in the lowlands and degrading aquatic habitat. Overburden stored in the highlands produces acidic runoff that enters the Wanagon River. Freeport states that overburden is placed at limestone-capped, monitored sites and that tailings are confined within engineered levees in the lowlands. Indonesian Environment Ministry data from 2004 recorded sediment levels far above legal limits. [Source: Wikipedia]

Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner wrote in the New York Times, “Satellite images quickly reveal the deepening spiral that Freeport has bored out of its Grasberg mine as it pursues a virtually bottomless store of gold hidden inside. They also show a spreading soot-colored bruise of almost a billion tons of mine waste that the company has dumped directly into a jungle river of what had been one of the world's last untouched landscapes. [Source: Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner, New York Times, December 27, 2005 -]

“By Freeport's own estimates,” it “will generate an estimated six billion tons of waste before it is through - more than twice as much earth as was excavated for the Panama Canal. Much of that waste has already been dumped in the mountains surrounding the mine or down a system of rivers that descends steeply onto the island's low-lying wetlands, close to Lorentz National Park, a pristine rain forest that has been granted special status by the United Nations. -

“In 2005 Freeport told the Indonesian government that the waste rock in the highlands, 900 feet deep in places, now covers about three square miles. An internal ministry memorandum from 2000 said the mine waste had killed all life in the rivers, and said that this violated the criminal section of the 1997 environmental law. A multimillion-dollar 2002 study by an American consulting company, Parametrix, paid for by Freeport and its joint venture partner, Rio Tinto, and not previously made public, noted that the rivers upstream and the wetlands inundated with waste were now "unsuitable for aquatic life." -

RELATED ARTICLES:

FREEPORT (GRASBERG) GOLD AND COPPER MINE IN PAPUA, INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

LORENTZ NATIONAL PARK AND THE HIGHEST MOUNTAIN IN OCEANIA factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SOUTHERN PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF WEST NEW GUINEA — EIPO, DAMAL, EKAGI — AND THEIR HISTORY, LIFE AND SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Polluted Rivers, Acidic Groundwater and Mountains of Waste from the Freeport Mine

Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner wrote in the New York Times, “Down below, nearly 90 square miles of wetlands, once one of the richest freshwater habitats in the world, are virtually buried in mine waste, called tailings, with levels of copper and sediment so high that almost all fish have disappeared, according to environment ministry documents. The waste, the consistency and color of wet cement, belts down the rivers, and inundates and smothers all in its path, said Russell Dodt, an Australian civil engineer who managed the waste on the wetlands for 10 years until 2004 for Freeport. About a third of the waste has moved into the coastal estuary, an essential breeding ground for fish, and much of that "was ripped out to sea by the falling tide that acted like a big vacuum cleaner," he said. [Source: Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner, New York Times, December 27, 2005 -]

“A perpetual worry is where to put all the mine's waste - accumulating at a rate of some 700,000 tons a day. The danger is that the waste rock atop the mountain will trickle out acids into the honeycomb of caverns and caves beneath the mine in a wet climate that gets up to 12 feet of rain a year, say environmental experts who have worked at the mine. Stuart Miller, an Australian geochemist who manages Freeport's waste rock, said at a mining conference in 2003 that the first acid runoffs began in 1993. The company can curb much of it today, he said, by blending in the mountain's abundant limestone with the potentially acid producing rock, which is also plentiful. Freeport also says that the company collects the acid runoff and neutralizes it. -

“But before 2004, the report obtained by The Times by Parametrix, the consulting company who did the study for Freeport, said that the mine had "an excess of acid-generating material." A geologist who worked at the mine, who declined to be identified because of fear of jeopardizing future employment, said acids were already flowing into the groundwater. Bright green-colored springs could be seen spouting several miles away, he said, a tell-tale sign that the acids had leached out copper. "That meant the acid water traveled a long way," he said. -

“Freeport says that the springs are "located several miles from our operations in the Lorentz World Heritage site and are not associated with our operations." The geologist agreed that the springs probably were in the Lorentz park, and said this showed that acids and copper from the mine were affecting the park, considered a world treasure for its ecological diversity. In the lowlands, the levees needed to contain the waste will eventually reach more than 70 feet high in some places, the company says. -

“Freeport says that the tailings are not toxic and that the river it uses for its waste meets Indonesian and American drinking water standards for dissolved metals. The coastal estuary, it says, is a "functioning ecosystem." The Parametrix report shows copper levels in surface waters high enough to kill sensitive aquatic life in a short time, said Ann Maest, a geochemist who consults on mining issues. The report showed that nearly half of the sediment samples in parts of the coastal estuary were toxic to the sensitive aquatic organisms at the bottom of the food chain, she said. The amount of sediment presents another problem. Too many suspended solids in water can smother aquatic life. Indonesian law says they should not exceed 400 milligrams per liter.Freeport's waste contained 37,500 milligrams as the river entered the lowlands, according to an environment ministry's field report in 2004, and 7,500 milligrams as the river entered the Arafura Sea.” -

Pressure on Freeport to Clean Up the Mine

Freeport told the New York Times in the mid 2000s that it aimed to minimize environmental impacts while maximizing shareholder benefits. The company said local and regional governments had approved its waste management plans, and the central government had cleared its environmental impact statement. Freeport reported spending $30 million on environmental programs in 2004 and planting 50,000 mangrove seedlings as part of reclamation efforts. It also claimed that cash crops could grow on treated waste and had started demonstration projects. However, journalists were repeatedly denied access to the mine and surrounding areas, which require special permission. [Source: Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner, New York Times, Dec. 27, 2005]

Two U.S. environmental experts, Harvey Himberg and David Nelson, visited the mine and issued a report criticizing Freeport for dumping massive amounts of waste into rivers—a practice not permitted in the U.S. Freeport tried to block the report, and only a redacted version was released. An uncensored copy later reached The Times. Freeport rejected the report’s conclusions, arguing that alternatives like storage dams or pipelines were impractical or risky due to earthquakes, floods, and costs. Auditors found these arguments unconvincing, noting that waste often overflowed riverbanks, killing vegetation, and that the problems persist on a larger scale.

The Indonesian government has been largely reluctant to enforce environmental standards. In 2000, Environment Minister Sonny Keraf, sympathetic to Papuans, pressured Freeport to stop using rivers for waste, insisting the company properly dispose of its waste rather than paying locals to stay silent. He and his deputy recommended pipe systems and sturdier levees, but enforcement failed. A 2001 ministerial change to Nabiel Makarim further reduced oversight. Freeport still lacks a permit under Indonesia’s 1999 hazardous waste regulations, though the Environment Ministry is negotiating with the company.

Earlier, in 1995, the U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation revoked Freeport’s political-risk insurance over environmental and human rights concerns—a first in the agency’s history—though the policy was briefly reinstated after negotiations. Despite later audits clearing Freeport, controversies continued, including Norwegian government divestment from Freeport and partner Rio Tinto for environmental reasons.

In 2006, Indonesia’s State Minister for the Environment, Rachmat Witoelar, ordered PT Freeport Indonesia to improve its environmental management at the Grasberg mine, warning of possible legal action. A government audit found the mine violated standards for acid drainage and tailings disposal, including dumping tailings—containing harmful chemicals and heavy metals—into the Arafuru estuary without a permit. Activists estimated hundreds of thousands of tons of tailings were dumped daily, forming piles over 50 kilometers long. [Source: Tb. Arie Rukmantara, Jakarta Post, March 24, 2006]

While some Freeport operations, such as its milling and dewatering plants, met environmental standards, the audit highlighted serious concerns about tailings management. The review was part of Indonesia’s PROPER program, which ranks companies on environmental compliance using a color-coded system; Freeport risked a “red” rating for poor environmental management. Freeport pledged cooperation, but activists criticized the government for issuing only a warning, arguing decades of environmental damage warranted legal action. Former officials noted that historical oversight of Freeport had been weak, allowing persistent environmental harm.

Freeport's Intelligence Operation and Ties to Indonesian Military Officers

From 1998 to 2004, Freeport McMoRan paid at least $20 million directly to Indonesian military and police officers in Papua, with some individuals receiving up to $150,000. Payments were documented under vague categories like “food costs” but were widely considered bribes, illegal under Indonesian law. The system was reportedly established after 1996 riots threatened the mine, and included infrastructure, vehicles, and travel benefits. By 2003, following stricter U.S. accounting laws, payments were shifted to units rather than individuals. [Sources: Jane Perlez & Raymond Bonner, New York Times, December 27, 2005; Jim Mann, Los Angeles Times, November 5, 1995]

Freeport claimed the payments were legal, necessary for security, and mandated by its 1967/1991 contract with Indonesia, though independent sources and experts found no such requirement. Critics argued the funds should have gone through official channels to avoid corruption and comply with U.S. anti-bribery laws.

The payments coincided with human rights abuses in Papua. Reports documented killings, torture, arbitrary detention, and property destruction by Indonesian security forces. While no direct link was established, local communities increasingly associated Freeport with these abuses, including use of company facilities by military units. Freeport also gave funds to paramilitary forces cited for brutality in the U.S. State Department’s 2003 human rights report.

Between the late 1990s and early 2000s, Freeport McMoRan, with help from Indonesian military intelligence, conducted covert surveillance on its environmental opponents. The company intercepted emails and monitored phone calls to track activists and local tribes who were critical of the mine and concerned about the limited benefits they received. Freeport even created a fake environmental group online to collect login information, allowing it to access participants’ emails. Company lawyers reportedly reviewed the program and concluded that reading messages sent from abroad was not explicitly illegal.

Violence Related to the Freeport Mine

The Freeport Grasberg mine in Papua has long been a flashpoint for violence and political tension. Armed attacks occurred in 2002, 2009, and 2011, causing multiple deaths and injuries, often linked to local resentment over environmental damage, limited economic benefits for Papuans, and controversial payments to Indonesian security forces. [Sources: Jane Perlez & Raymond Bonner, New York Times, Dec. 27, 2005; Ellen Nakashima, Washington Post, June 25, 2006; Niniek Karmini, AP, July 16–22, 2009]

Since the 1970s, the mine has faced arson, bombings, and blockades, while Indonesian military units protecting the site have killed dozens. Between 1975 and 1997, an estimated 160 people were killed by military operations in the mine area. In 1994 and 1996, military crackdowns followed worker deaths or minor incidents, resulting in multiple deaths, disappearances, and three days of rioting that caused millions in damages. Violence continued in the 2000s: in May 2002, attacks on Freeport facilities by suspected OPM members prompted military killings of demonstrators.

In July 2009, at least a dozen people were killed or wounded in ambushes along a road leading to the Freeport mine, prompting a massive security operation in the militarized zone that is off limits to foreign journalists. Associated Press reported: At least 15 people, most of them police officers, have been killed or wounded along the 40-mile (65-kilometer) road from Freeport's sprawling Grasberg mining complex to the mountain mining town of Timika. [Source: Niniek Karmini, Associated Press, July 16 2009 ]

“The assailants shot and killed a 29-year-old Australian and a Freeport security guard, while a policeman fell to his death in a ravine as he sought cover. Five police officers were injured by gunfire and taken to a Freeport-owned hospital. Papua's chief detective, Bambang Rudi, said. They were shot in the stomach, hand and thigh when "they were sprayed with bullets," National Police spokesman Brig. Gen. Sulistyo Ishak said.

About a week later, gunmen opened fire on buses carrying Freeport employees in restive Papua province, killing two people. An Associated Press reporter was told by a policeman who witnessed the shooting that a police vehicle escorting the convoy flipped. Several injured officers were taken to a local clinic, the AP reporter said, one of them in critical condition. Two body bags were later seen being removed. The police officer did not think any Freeport employees had been hurt. [Source: Associated Press, July 22, 2009]

Killing of Two Americans Near the Freeport Mine

In August 2002, two American teachers and an Indonesian colleague were killed and 14 others were wounded in an ambush in Papua near the Freeport-McMoRan mine on company road patrolled by the military that Freeport had paid to protect its employees. The teachers taught at Freeport International School in Papua. They were in a convoy of vehicles carrying mostly U.S. teachers and their families from the school. It was the worst spate of violence involving foreigners in Papua.

The attack was initially blamed on Papuan separatists but the fact it was carried out with automatic weapons, including M-16s led many to believed that Indonesian security forces were behind it not separatists who normally didn’t have access to such weapons. The attack was believed to have been ordered by military commanders in the area as a form of extortion. Freeport-McMoRan had recently cut payments to the military in the area and the killings, it was said, were how the military expressed its disapproval.

The incident caused the United States to thinks twice about establishing better relations and offering more military assistance to the Indonesian government. It also put foreign investors on the alert that Indonesia was not necessarily a safe place to do business. In January 2001, the United States government decided not let the matter affect military ties with Indonesia.

The F.B.I. investigated the case and in 2005 said the reasons for the killings have not been determined. Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner wrote in the New York Times, “The United States indicted a Papuan, Anthonius Wamang, in 2004. But it has yet to receive the full cooperation of the military, several American officials said. Freeport employees and American officials said the killings could have been part of a turf war between the military and the police, each of which wanted access to Freeport payments. An initial report by the Indonesian police pointed to the Indonesia military, and some Freeport and Bush administration officials have said they suspect some level of military involvement. The police report suggested that the motivation was that Freeport was threatening to cut its support to soldiers. Soldiers assigned to Papua have "high expectations," the report said, but recently, "their perks, such as vehicles, telephones, etc., were reduced." [Source: Jane Perlez and Raymond Bonner, New York Times, December 27, 2005 -]

Labor Disputes and Strikes at Freeport Mine

Strikes have periodically disrupted production. Notable actions occurred in 2011 (involving 70 percent of the workforce), 2014 (over safety concerns), and 2017 (with about 5,000 workers participating for more than four months).

In 2011, workers at the Freeport mine in Papua went on strike, demanding higher wages. The strike lasted for three months, caused copper and gold output to drop 15 percent and was Indonesia's longest-ever industrial dispute. When the strike was over, the BBC reported: “The decision to end the three-month-long strike came after Freeport bosses agreed to an increase in wages. The strike crippled production at the mine.Freeport-McMoran has always been seen as one of the most powerful foreign companies in the country, with strong connections to the Indonesian government - but even the government was unable to solve this industrial dispute, says the BBC's Karishma Vaswani in Jakarta. [Source: BBC, December 14, 2011]

It took a 37 percent increase in wages, improved housing allowances, educational assistance and a retirement savings plan for workers to agree to a deal. This is being seen as a partial victory for Freeport's workers - even though their initial demands called for much higher wages, our correspondent says. The US firm did manage to put in some conditions of its own, however, agreeing with union leaders that future wage negotiations would be based on living costs and the competitiveness of wages within Indonesia. Our correspondent says that was presumably an attempt to prevent such a strike happening again.

Accidents at Grasberg Mine

Major accidents include an eight-fatality landslide in 2003, fatal sulfur-fume exposure that same year, a 2013 training-tunnel collapse that killed 28 workers, and a 2025 landslide that killed seven workers. Some incidents prompted accusations of negligence; others were later ruled natural events. [Source: Wikipedia]

The May 2013 training tunnel accident involved 38 workers. It was was one of the worst mining disasters in Indonesia's history. Immediately after the collapse, Reuters reported: “At least 40 workers had been in an underground training facility when it collapsed, the statement said. Three people escaped unhurt, while four were rescued and received medical treatment. The collapse is one of a series of worker-related incidents at the mine in recent months. In late May 2013, another tunnel at the Freeport mine collapsed. [Source: Michael Taylor, Reuters, May 14, 2013 ]

The tunnel collapses at Freeport’s Grasberg mine in 2013 raised concerns about underground safety and the company’s ability to meet shipment commitments. Industry observers questioned whether the incidents reflected seismic activity or deeper structural problems, complicating Freeport’s plan to convert Grasberg into the world’s largest underground mine after open-pit operations end in 2016. Following the deadly May 14 accident that killed 28 miners, Freeport halted production and declared force majeure. Unions representing most of the 24,000-plus workforce threatened a strike unless managers deemed responsible were suspended. The strike was canceled after Freeport agreed to sideline five officials during the investigation. Production remained shut pending government-mandated inquiries, causing significant losses—about three million pounds of copper and 3,000 ounces of gold per day, totaling roughly 80 million pounds of copper and 80,000 ounces of gold between May 15 and June 11.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025