HISTORY OF PAPUA

The Papua region has been visited by global traders since the beginning of the 7th century. European nations kept a presence in the region in the 16th century in the pursuit of various spices. The people of Papua are culturally, linguistically and racially different from the other people of Indonesia and have no historical links with them. They are Papuans of the Melanesian culture, and are even more different than the other diverse groups of Indonesia are from each other. The modern world has quite late to Papua.

West Papua became part of the Dutch East Indies in 1828 as West Papua Nugini (or New Guinea), which was then known as West Irian. The region remained occupied by the Netherlands long after Indonesia claimed its independence in 1949 in part because of the large reserves of oil in Bird’s Head area around Sorong. After West Irian’s long freedom struggle, the province finally became part of Indonesia in 1969.

In Europe the people went from the Stone Age to a cash economy over a period of around 4,000 years. The people in Papua have made the same transformation in a generation. In the 1970s, most men in the region were warriors who engaged in continuous revenge-driven wars. Only a few decades ago tribesmen would have fled in terror and hidden their children in the forest if a plane flew too close their village.

Most of inhabitants of Papua are descendants of hunter-gatherers or slash-and-burn mountain farmers who have traditionally lived with members of their clans in small villages and practiced clan warfare until the 1970s. Linguist have identified 250 languages on Papua, half of them spoken by less than a thousand people. In some remote region villages less than a day's walk apart speak completely different languages.

Based on regulation No. 45 Year 1999, the region covering the bird head of Papua Island and the small islands around it became Papua province. In February 2007, this province was officially named West Papua.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN NORTHERN PAPUA AND THE BIRD'S HEAD (VOGELKOP) OF NEW GUINEA factsanddetails.com

NORTHWEST PAPUA AND THE BIRDHEAD OF NEW GUINEA factsanddetails.com

HIGHLAND GROUPS OF WEST NEW GUINEA — EIPO, DAMAL, EKAGI — AND THEIR HISTORY, LIFE AND SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

DANI AND PEOPLE OF THE BALIEM VALLEY: HISTORY, RELIGION, WHERE THEY LIVE factsanddetails.com

BALIEM VALLEY: HISTORY, PEOPLE, TRAVEL, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SOUTHERN LOWLANDS OF PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

ASMAT: HISTORY, RELIGION AND HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI PEOPLE: HISTORY, CANNIBALISM, CONTACT WITH WESTERNERS factsanddetails.com

FREEPORT (GRASBERG) GOLD AND COPPER MINE IN PAPUA, INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

PROBLEMS AT THE FREEPORT MINE: VIOLENCE, POLLUTION AND BRIBES TO THE MILITARY factsanddetails.com

Early History of New Guinea

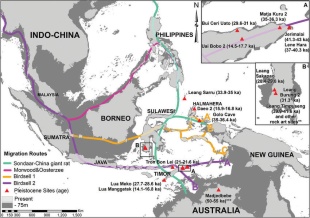

New Guinea was first settled about 40,000 to 50,000 years ago, around the same time as Australia. Archaeological evidence shows that 40,000 years ago, some of the first farmers came to the Indonesian side of New Guinea. Flaked stone, bone, and shell artifacts dated to 28,000 years before present have been found in Kilu Cave.Buka Island, New Guinea. Buka Island is near Bougainville Island which is close to the Solomon Islands than the main part of Papua New Guinea, [Source: Wikipedia]

Some of the earliest evidence of modern humans outside of Africa and the Middle East is not in Asia or Europe but in Australia. There is evidence of human habitation at Malakunaja in northern Australia dated to 50,000 years ago and evidence of human habitation at Lake Mungo in southern Australia dated to 45,000 years ago. The earliest evidence of humans in Australia suggests that some from of boatbuilding had been developed at that time. Although the earliest inhabitants may have walked from New Guinea at some point they would have had to use some sort of boat to get across the Java Trench which created a water barrier between Indonesia and New Guinea.

About 40,000 years ago, it is believed a boat with a group of humans landed on New Guinea for the first time. From archaeological, linguistic and biological evidence, it is thought that these first visitors, the Papuans, are the oldest human residents of New Guinea. Much later on, probably about 1,600 B.C., seafaring people that had set off thousands of years before from Taiwan also reached New Guinea. [Source: WWF]

Evidence from Mololo Cave on Waigeo Island in the Raja Ampat archipelago of West Papua, Indonesia — between North Maluku Island in Indonesia and northeast New Guinea — indicates that early seafarers navigated to the island at least 55,000 years ago. Archaeologists unearthed stone artifacts, animal bones from marsupials, megabats, and ground-dwelling birds and the oldest known plant artefact outside Africa—a carved tree resin object likely used as fuel — attesting to human occupation in the cave at that early date. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2024]

See Separate Article: FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Oldest High-Altitude Settlements Discovered in Papua New Guinea

In 2010, AFP reported, The world's oldest known high-altitude human settlements, dating back up to 49,000 years, have been found sealed in volcanic ash in Papua New Guinea mountains, archaeologists said Friday. Researchers have unearthed the remains of about six camps, including fragments of stone tools and food, in an area near the town of Kokoda, said an archaeologist on the team, Andrew Fairbairn. [Source: AFP, October 1, 2010]

"What we've got there are basically a series of campsites, that's what they look like anyway. The remains of fires, stone tools, that kind of thing, on ridgetops," the University of Queensland academic told AFP. "It's not like a village or anything like that, they are these campsite areas that have been repeatedly used."

Fairbairn said the settlements are at about 2,000 meters (6,600 feet) and believed to be the oldest evidence of our human ancestors, Homo sapiens, inhabiting a high-altitude environment. "For Homo sapiens, this is the earliest for us, for modern humans," he said. "The nearest after this is round about 30,000 years ago in Tibet, and there's some in the Ethiopian highlands at around about the same type of age."

Fairbairn said he had been shocked to discover the age of the finds, using radio carbon dating, because this suggested humans had been living in the cold, wet and inhospitable highlands at the height of the last Ice Age. "We didn't expect to find anything of that early age," he said. The findings, published in the journal Science, suggest that the prehistoric highlanders of Papua New Guinea's Ivane Valley in the Owen Stanley Range Mountain made stone tools, hunted small animals and ate yams and nuts.

But why they chose to dwell in the harsh conditions of the highlands, where temperatures would have dipped below freezing, rather than remain in the warmer coastal areas, remains a mystery. "Papua New Guinea's mountains have long held surprises for the scientific community and here is another one — maybe they were the home of Homo sapiens' earliest mountaineers," Fairbairn said.

Early History of Papua

Long before European arrived in Indonesia, the Makassarese, Bajau, and the Bugis—Indonesian ethnic groups—travelled as far east as the Aru Islands, off New Guinea, where they traded in the skins of birds of paradise and medicinal masoya bark, and to northern Australia, where they exchanged shells, birds'-nests and mother-of-pearl for knives and salt with Aboriginal tribes. Throughout the coastal areas of northern Australia, there is much evidence of a significant Bugis presence. Each year, the Bugis sailors would sail down on the northwestern monsoon in their wooden pinisi. They would stay in Australian waters for several months to trade and take trepang (dried sea cucumber) before returning to Makassar on the dry season off shore winds.

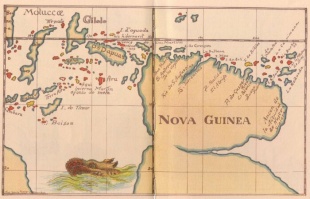

Muslim Javanese traders came to what is now Papua hundred of years ago to trade porcelain and cloth for pearls, bird of paradise feathers and slaves. Portuguese explorers sailed along the north coast of Papua in the 1500s. After their first encounter with New Guinea in 1511 the Portuguese named the island “Ilhas dos Papuans” (“Island of the Fuzzy Haired”), using the Malay word “papuwah”. Early Dutch explorers called it New Guinea because the black inhabitants reminded them of the blacks that lived in Guinea in western Africa and later called the western half Dutch New Guinea.

In 1660 the Dutch recognized the Sultan of Tidore’s sovereignty over New Guinea. By that time the sultan was controlled by the Dutch, meaning the Dutch effectively had jurisdiction over New Guinea. The British unsuccessfully tried to establish a settlement at Manokwari in present-day Papua in 1793.

The Dutch were able to establish a few trading outposts but otherwise colonized the region they called Dutch New Guinea very little. In 1824, they and the British decided that western half of New Guinea would be part of the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch tried unsuccessfully to set up a settlement in Lobo (near Kaimana) and didn’t begin developing the area until 1896 when outpost were set up at Manokwari and Fak-Fak in response to Australia’s claims on New Guinea. Even after that development was limited before World War II except for exploration by American mining companies.

European Exploration

European traders looking for spices began arriving in the early 16th century, and have left historical footprints in the area with names such as Bougainville, Cape d’Urville and the Torres Straits. It was the Dutch who made the most lasting impact on the island, when in 1828 they formally made Papua a Dutch Territory until 1962.

The Asmat region of Papua was explored from the 16th to the 19th centuries by the Netherlands and Britain but the remoteness and lack of resources essentially cut the region off from colonization. The first contact by Europeans was made by the Dutch trader, Jan Carstens, in 1623. Captain Cook arrived in the area in 1770. Occasional contacts were made over the next 50 years, The Dutch government didn’t formally set up a post in the Asmat region until 1938. Permanent contact has been maintained since the early 1950s. The original Dutch post, Agats, is now the Asmat’s main trading and mission town and administrative center.

The first Europeans to really penetrate into Papua were missionaries. In 1855 German missionaries established a settlement near Manokwari.

Papua in World War II

In early 1944, the Allied forces under General MacArthur, launched an operation from what is now Papua New Guinea to liberate the Dutch East Indies from Japanese occupation. Much of the fighting took place in and along the north coast of what is now Papua (Irian Jaya) and in caves on the nearby island of Biak. People knew little about this part of the world until then.

The first objective of the operation was to capture Hollandia (Jayapura) which was achieved with the help of more than 80,000 Allied troops in what was the largest amphibious operation of the war in the southwestern Pacific. The second objective, the capture of Sarmi, was achieved despite heavy Japanese resistance. The third and primary object was the capture of Biak to gain access to its airfields. Allied intelligence underestimated the Japanese presence in the area and a series of bloody battles was the result. Fighting also took place along the souther coast of Irian Jaya. The Allies captured Merauke, which they thought the Japanese might use to launch an attack on Australia.

In April 1944, U.S. forces occupied the town of Hollandia (now called Jayapura) in Papua, and in mid-September Australian troops landed on Morotai, Halmahera (Maluku); toward the end of the month, Allied planes bombed Jakarta (as Batavia had been renamed) for the first time.

The move into Indonesia’s islands was part of the island hopping operation to free the Philippines. After Biak was captured the airfields and bases were used to capture islands between New Guinea and the Philippines. The Americans captured the Japanese air bases on Morotai, an island near Halmahera, in the northern Moluccas and used that airfield to bomb Manila. A Japanese soldier hide out on Morotai island until 1973 not realizing the war was over.

Papua After World War II

After World War II, the Dutch retook control of Papua and used it as a place exile prisoners. The infamous Bovem Digul prison camp was set up in malaria-infested Tanahmerah. Among those sent there were the nationalist Mohammed Hatta and Sultan Syahir.

When Indonesia became independent in 1949, the Dutch retained control of Papua. Indonesia didn’t get it. In an effort to thwart attempts by Indonesia to gain control of the region, the Dutch encouraged Papuan nationalism and built schools and trained professionals with the aim of preparing them for self rule in 1970.

During the 1949 Round Table Conference, the Dutch had refused to discuss the status of this territory, which, upon recognition of Indonesian independence, was still unresolved. Conflict over the issue escalated during the early 1960s, as the Dutch prepared to declare a separate state, and Sukarno responded with a military campaign. In August 1962, the Dutch were pressed by world opinion to turn over West New Guinea to the UN, which permitted Indonesia to administer the territory for a five-year period until an unspecified “Act of Free Choice” could be held. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Most of Papua was closed off to the outside world until the 1950s when Christian missionaries began flying, hiking and boating into the interior. This is sometimes call the “Contact Era” because many ethnic groups had their first contact with outsiders at that time.

Disappearance of Michael Rockefeller

One of the most famous missing person cases is the 1961 disappearance of Michael Rockefeller, the heir to the Rockefeller oil and US Steel fortune and the son of Nelson Rockefeller, the American vice president during the Ford administration. After graduating from Yale with a degree in ethnology, the twenty-two-year-old Michael went on an expedition to the Asmat area of New Guinea, where he traded tobacco and steel fishing hooks for carved Asmat bis-poles to add to the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York ♢]

Rockefeller disappeared on his second expedition to New Guinea. One of the goals of the expedition to the Asmat region was to purchase as many woodcarvings as possible. On his first visit Michael had been deeply impressed by the Asmat sculptures, and planned to display these at an exhibition in the United States. Today the Metropolitan Museum has an outstanding collection of Asmat art, the majority of which was collected in 1961 by Michael C. Rockefeller. A group of 17 poles from the village of Otjanep was delivered to the museum after his disappearance.

Michael Rockefeller was last seen on November 16, 1961 in a jerry-rigged catamaran bound for the village of Otjaneps. He had left the town of Agats with two mission boys and the Dutch anthropologist Renee Wassing when the boat’s 18-horsepower motor conked out in the mouth of the Sirets river. The two boys immediately started swimming for shoreline to get help and Rockefeller and Davis spent the night on the boat as it drifted out to sea. The next morning Rockefeller could still see the shore. He tied his steel rimmed glasses around his neck and attached himself to empty oil cans for buoyancy. His last words were "I think I can make it." ♢

Rockefeller was never seen again. The Dutch navy, various missionary boats, the Australian Air Force and an American aircraft carrier participated in the search. Nelson Rockefeller and Michael's twin sister Mary arrived in a chartered plane and hired 12 Neptune aircraft to search the sea and paid the Asmat large amounts of black tobacco in return for participating in search parties. The search lasted for 10 days before it was abandoned. ♢

The Lawrence and Lorne Blair suggest that Rockefeller was either eaten by sharks, drowned or was eaten by Asmat headhunters. To back up the last hypothesis they suggest he might have been killed in revenge for the murder of four Asmat warleaders by a Dutch government patrol in 1958. They also point out that seems likely he made it to land because it is possible to touch the sea bottom three kilometers from shore and wade in from a kilometers and half out. Locals say they are few sharks in the water and the only thing they worry about is stepping on a stingray. ♢

An elder war leader in Otjanep told the Blairs that after returning from fishing some of his friends found Rockefeller laying in the mud, breathing heavily. Relatives of the friends had been killed by the Dutch and they speared Rockefeller out of revenge and then dragged his body back to the village where his head was cut off with a bamboo knife. The cuts were cleaned out and the body was thrown on a fire. The meat was divided among the people of the village and the most important men ate the brains. ♢

Indonesia Fights for Control of Papua

Papua—known at various times as Dutch New Guinea, West New Guinea, West Irian, Irian Jaya, and today Papua—was the only part of present-day Indonesia that did not gain independence from the Netherlands in 1949. After Indonesian independence, the territory remained under Dutch control, even as Jakarta insisted it was an integral part of the new republic. [Source: Library of Congress; Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Many Papuans opposed incorporation into Indonesia. While still under Dutch rule, Papuan leaders proclaimed the independent state of Papua on December 1, 1961, raising their own flag and asserting a separate national identity. At the same time, most Indonesian political parties maintained that Dutch New Guinea rightfully belonged to Indonesia. An arms agreement with the Soviet Union in 1960 strengthened Indonesia’s military capabilities and diplomatic position, enabling President Sukarno to confront the Dutch more forcefully.

Tensions escalated as Indonesia broke diplomatic relations with the Netherlands in 1960 and established the Mandala Command, later known as the Army Strategic Reserve Command (Kostrad), to “recover” the territory. Armed clashes between Indonesian and Dutch forces followed in 1961, and in early 1962 Sukarno ordered paratroopers and other forces to infiltrate the region. These troops were not widely welcomed by the local population, many of whom regarded them as invaders rather than liberators and resisted Indonesian control.

Indonesia Gains Control of Papua Through a Rigged Assembly

To avoid a full-scale war, the Netherlands agreed under strong United States pressure—during the presidency of John F. Kennedy—to a compromise settlement over West New Guinea. In August 1962, a hastily conceived agreement transferred sovereignty first to the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority (UNTEA), supported by a military observation force to supervise a ceasefire. The United Nations formally assumed control on October 1, 1962, and in May 1963 transferred full administrative authority to Indonesia. The agreement stipulated that the Papuan population would later be given an opportunity to decide their political future in a referendum. [Source: Library of Congress, Ellen Nakashima, Washington Post, June 25, 2006]

Once Indonesia took control, the territory was renamed West Irian and later Irian Jaya, and Jakarta moved swiftly to suppress Papuan independence movements. Many Papuans rejected Indonesian rule from the outset, laying the foundations for decades of unrest and resistance.

The promised vote took place in 1969 in the form of the so-called Act of Free Choice, a UN-sanctioned and monitored process intended to determine whether Papua would remain part of Indonesia. Rather than a one-person, one-vote referendum, the Indonesian government selected 1,025 tribal leaders and community representatives to participate in a staged series of assemblies held at village, district, and provincial levels. Only these representatives were permitted to vote, and they unanimously approved integration with Indonesia. The United Nations General Assembly subsequently acknowledged the result and confirmed Indonesia’s sovereignty over the territory.

The legitimacy of the Act of Free Choice was widely questioned. Foreign observers, academics, and later declassified U.S. documents suggested that the process was deeply flawed and that participants were subjected to intimidation and coercion. Critics, including former UN officials, later described the vote as a sham. One Papuan participant recalled that refusal to vote for integration would have led to the burning of homes and the killing of families. Testimonies collected decades later, including those cited by Washington Post journalist Ellen Nakashima, reinforced claims that tribal elders were pressured with promises of prosperity and threats of violence—promises that many Papuans say were never fulfilled.

Ellen Nakashima wrote in the Washington Post, “Simon Wandikbo recalled that in 1969 a special vote was held to decide Papua's future. Simon's aunt was among 1,022 tribal elders selected to take part. The vote was sponsored by the United Nations, with U.S. support. The aunt, now dead, told him the elders were coerced into choosing to remain with Indonesia, he said. Studies by academics in the Netherlands and in Britain, as well as declassified U.S. documents, support her contention. "They promised that we would belong to a great nation and have great homes and we would be wealthy," Simon said his aunt told him. "That was in the 1960s. Now it's 2006. Nothing has changed — except for the worse." "They said we would never live in honai anymore," Worige added. "We're still in honai." [Source: Ellen Nakashima, Washington Post, June 25, 2006]

Following the 1969 vote, the territory was formally annexed as Indonesia’s twenty-sixth province. Opposition to Indonesian rule soon gave rise to low-level guerrilla activity led by the Organisasi Papua Merdeka (OPM, or Free Papua Movement), which sought independence. Although dissent was tightly controlled for decades, more open expressions of Papuan nationalism emerged after Indonesia’s political reforms in 1998. Meanwhile, the eastern half of the island of New Guinea—administered separately by Australia and the United Nations—became the independent nation of Papua New Guinea in 1975.

Sukarno, Suharto and Papua

In Indonesian-controlled Papua, Jakarta granted extensive logging, mining, and plantation concessions to domestic and foreign companies. Many Papuans complained that their land and resources were exploited without fair compensation and that they faced repression by the Indonesian military and state authorities. Officials also pursued aggressive modernization policies; one military commander famously declared in 1971 that by 1973 there would be “no more naked people” in the remote frontier province. These policies deepened Papuan grievances and entrenched a cycle of resistance, repression, and mistrust that has continued to shape the region’s relationship with the Indonesian state.

A connection between the Sukarno and Suharto eras was the ambition to build a unitary state whose territories would extend "from Sabang [an island northwest of Sumatra, also known as Pulau We] to Merauke [a town in southeastern Irian Jaya]." Although territorial claims against Malaysia were dropped in 1966, the western half of the island of New Guinea and East Timor, formerly Portuguese Timor, were incorporated into the republic. This expansion, however, stirred international criticism, particularly from Australia. [Source: Library of Congress *]

West New Guinea, as Irian Jaya was then known, had been brought under Indonesian administration on May 1, 1963 following a ceasefive between Indonesian and Dutch forces and a seven-months UN administration of the former Dutch colony. A plebiscite to determine the final political status of the territory was promised by 1969. But local resistance to Indonesian rule, in part the result of abuses by government officials, led to the organization of the Free Papua Movement (OPM) headed by local leaders and prominent exiles such as Nicholas Jouwe, a Papuan who had been vice chairman of the Dutch-sponsored New Guinea Council. Indonesian forces carried out pacification of local areas, especially in the central highland region where resistance was particularly stubborn. *

Although Sukarno had asserted that a plebiscite was unnecessary, acceding to international pressure, he agreed to hold it. After Sukarno was ousted in 1965 it fell to Suharto to complete the project begun by Sukarno. The Act of Free Choice provisions did not define precisely how a plebiscite would be implemented. Rather than working from the principle of one man-one vote, Indonesian authorities initiated a consensus-building process that supposedly was more in conformity with local traditions. During the summer of 1969, local councils were strongly pressured to approve unanimously incorporation into Indonesia. Ali Murtopo—with the military support of troops commanded by Sarwo Edhie Wibowo (1927–89)—arranged the campaign that, in mid-1969, produced a consensus among more than 1,000 designated local leaders in favor of integration with the Indonesian state. The UN General Assembly approved the outcome of the plebiscite in November, and West Irian (or Irian Barat), renamed Irian Jaya, became Indonesia's twenty-sixth province. *

The integration process did not go unopposed, however. Initial bitterness came from Papuans who had stood to benefit from a Dutch-sponsored independence. But resentment soon spread because of Jakarta’s placement of thousands of troops and officials in the territory, exploitation of natural resources (for example, by signing contracts for mining rights with the U.S. corporation Freeport-McMoRan Copper and Gold in 1967), encouragement of settlers from Java and elsewhere, and interference with local traditions such as dress and religious beliefs. OPM leaders declared Papua’s secession in 1971 and began a guerrilla resistance. Despite internal splits, OPM resistance continued throughout the New Order era, peaking in the mid-1980s and again in the mid-1990s, attracting a significant Sumatra military presence. *

Papua Separatist Movement

Many of the residents of Papua were clearly outraged by the way that the fair vote for independence was taken away from them. The real tribal communities, representing about 700,000 tribesmen, complained they were not counseled about the integration of Papua into Indonesia and the 1969 referendum was rigged. In 1969 there were rebellions in Biak and Enarotali.

Papuans who opposed Indonesian rule and favored taking action to win independence for Papuans formed the Free Papua Organization (OPM) in 1965. The OPM advocated the unification of Irian Jaya and the neighboring state of Papua New Guinea. Border incidents were frequent as small bands of OPM guerrillas sought sanctuary on Papua New Guinea territory. *

In 1971, opponents of Indonesian rule established a provisional revolutionary government. At one point the independence movement, with a poorly equipped army perhaps 10,000 strong, controlled an area of around 50,000 square miles, containing about a fifth of Papua's population. The people in the occupied area grew their own food and were able to survive without support from Indonesia.

In June 2000, 2,500 activists representing 250 tribal groups in Irian Jaya declared the region, which they call West Papua, a sovereign state. In October 2001, the region was granted limited autonomy by parliament, but many inhabitants, including independence rebels, rejected the measure and called for full independence. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007.]

Separatist Violence in Papua

There has been sporadic low-level violence over the independence issue in Papua. Thousands have died, most of them civilians killed by the Indonesian military in its effort to crush the separatists. Many Papuans compare their situation to that in Aceh. According to Associated Press: “A small, poorly armed separatist movement has battled Jakarta's rule ever since” Papua was taken over by Indonesia in 1969. “About 100,000 Papuans — one-sixth of the population — have died in military operations.”

Much of what occurred in Papua has gone on there in secret, outside the view of the Western media. In the early 2000s, there were many similarities between Papua and East Timor. There were a number of powerful militias and was it sometimes difficult to ascertain whose side they were on. Sometimes their main goal it seemed was to stir up trouble so they would remain relevant. Pro-Indonesian militias such as Satgas Merah Putih (Red and White Taskforce) were blamed for triggering violence.

Thousands of local people in Papua died in the 1970s and 80s when the Indonesian army crushed the independence movement there. In 1995, separatist stormed the Indonesian consulate in Vanimo in Papua New Guinea and protesters took to the streets in Tembagapua and Timika demanding independence for Papua. In 1996, 5,000 Papuans rioted and burned a market in Jayapura. Several people were killed. The same year several Europeans and Indonesians were taken hostages in the Baliem Valley. The Europeans were released but two Indonesians were killed.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025