MARIND

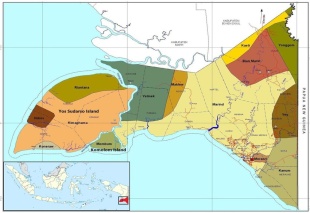

Marind is the general term for forty territorial groups (subtribes) residing in the province of South Papua in southeast New Guinea, Indonesia. Also known as the Kaja-kaja and Tugeri, they inhabit the southeastern coastal region of Papua (the western half of New Guinea), stretching from the southern entrance of the Muli Strait southeastward to roughly 30 kilometers beyond Merauke, with the enclave of Kondo located some distance inland from the international border. Farther inland, they occupy the upper Bulaka River area and all the land eastward to the Eli and Bian rivers, a region commonly known as the Okaba Hinterland. Their territory also encompasses the Bian and Kumbe river valleys and part of the lower Maro, including the land in between these rivers. [Source: J. Van Baal, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

The landscape of the area where they Marind live consists primarily of lowland savanna interspersed with swamps, while the upper river areas feature low hills and additional swampy terrain. Local resources include coconuts on sandy soils, sago in the swamps, eucalyptus on the savanna, wallabies in the grasslands, and abundant fish in both rivers and coastal waters. The climate is monsoonal, with heavy rainfall during the northwest monsoon from late December to April, and cooler conditions when the trade winds blow from June to early October. The transitional periods are typically hot and humid.

Marind Population in 2010, according to Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity by the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (2015), was 37,558. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project in the 2020s the population of: 1) Southeast Marind was 12,000; 2) of Bian Marind was 3,900. When the Marind region came under government control in 1902, the Marind population numbered roughly 8,000 along the coast and up to 6,000 in the interior. By 1950 their numbers had fallen by more than half, largely because of introduced diseases. Pacification also contributed indirectly to the decline by bringing an end to the kidnapping of children from neighboring groups, who had long been targets of Marind head-hunting raids. Since the Marind population had already been shrinking well before pacification, the adoption of these abducted children had become an important means of sustaining their numbers.

Marind Languages form a small family of the Trans–New Guinea language phylum of Papuan languages. There are several languages and dialects in the Marind family, including the eastern and western Marind dialects along the coast, as well as at least three inland dialects. The Upper Bian people speak a dialect that is classified as a separate language and is closely related to Marind.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SOUTHERN LOWLANDS OF PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

KIMAM PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

ASMAT: HISTORY, RELIGION AND HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

ASMAT LIFE: SOCIETY, MARRIAGE, FOOD, VILLAGES, WORK factsanddetails.com

ASMAT CULTURE: MUSIC, FOLKLORE, CEREMONIES, BODY ADORNMENT factsanddetails.com

ASMAT ART: BIS POLES, SPIRIT CANOES, BODY MASKS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI PEOPLE: HISTORY, CANNIBALISM, CONTACT WITH WESTERNERS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI LIFE AND SOCIETY: RELIGION, FOOD AND TREEHOUSES factsanddetails.com

ASMAT AND KOROWAI COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

Marind History

The Marind are thought to have entered their present territory from the north. Their closest linguistic and cultural relatives are the Boazi of the Middle Fly region of present-day southwestern Papua New Guinea, who are also organized into subtribes. A major difference, however, is that the Boazi subtribes fought among themselves, whereas Marind head-hunting raids targeted distant groups and generally spared neighboring non-Marind communities. As a result, the Marind lived in relative peace with most surrounding peoples, though non–head-hunting disputes did occur among Marind groups. [Source: J. Van Baal, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia ]

Historically, the Marind were renowned for their headhunting, always directed at outsiders. The practice was tied to their belief system and played a central role in newborn name-giving rituals. A captured skull was thought to hold a mana-like potency. From the 1870s to about 1910, the Boigu, Dauan, and Saibai peoples—along with other nearby Papuan groups—were harassed by Marind-anim raiders often referred to in contemporary accounts as “Tuger” or “Tugeri.”

During the 20th century, Marind society underwent profound transformation. The Dutch colonial administration outlawed headhunting, ritual homosexuality, and group sexual rites in which multiple men had intercourse with a single woman—practices that had accelerated the spread of sexually transmitted infections. A major epidemic of granuloma inguinale (donovanosis) erupted after 1912, compounding an earlier decline in birthrates associated with the introduction of gonorrhea into the region.

The Missionary of the Sacred Heart Petrus Vertenten drew the Dutch government’s attention to the increasingly dire situation, as disease and cultural practices placed the Marind at risk of extinction. Christian missions and the establishment of schools aimed at assimilation further reshaped Marind society.

By the early 1980s, the Dutch anthropologist Jan van Baal, who had conducted extensive research among the Marind and served as Governor of Netherlands New Guinea (1953–1958), wrote that traditional Marind culture had largely disappeared. The Marind were also studied by several other ethnographers and missionaries, including the Swiss Paul Wirz and the German Hans Nevermann.

Marind Society and Kinship

Traditionally, Marind society was built around a clan system. The Marind tribe was divided into two halves, called moities, each consisting of several patrilineal clans, called boans. , which were further divided into subclans. Social life depended on the networks formed through these subclans, clans, kin groups, and the two moieties spread across both inland and coastal communities. These ties were strengthened through shared religious beliefs and cult activities. [Source: J. Van Baal, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; Wikipedia]

Descent among the Marind is strictly patrilineal (through the male lone). Most people married within their own subtribe, although marriages between different communities were not uncommon, even across long distances. Because Marind groups often traveled and interacted with one another, the clans and subclans—each with its own totems and totemic ties—were grouped into nine (sometimes ten) superclans. These superclan names acted as markers of identity when traveling between communities. The Marind use Dakota-type kin terms, which allow speakers to make fine distinctions based on age within the same generation.

Studies of marriage practices show that the clans were also arranged into four exogamous kin groups, meaning people had to marry outside their group. Only one of these groups has a specific name. All four appear in every subtribe, and everywhere they are paired to form the two moieties: Geb-zé and Sami-rek. These moieties play an important role in ritual life. In some coastal and many inland subtribes—especially on the upper Bian—the moieties themselves are exogamous.

Marind communities consisted of several extended families living near one another. Each extended family traced its origin to a mythological ancestor. Ancestor veneration centered on these mythic beings—dema figures who appeared in myths and acted as culture heroes who shaped the world and introduced plants, animals, and cultural knowledge. These ancestors were often linked to plant or animal forms. Although this system resembled totemism, it did not usually involve food taboos. Totems appeared mainly in myths and in the design of ritual objects.

Marind Religion

Most Marind today are Christians—primarily Catholic, with a minority of Protestants. According to the Christian-group Joshua Project: 1) 65 percent of Southeast Marind are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being two to five percent; and 2) 64 percent of Bian Marind are Christians, with the estimated number of Evangelicals being five to 10 percent.

Although religious beliefs and practices have changed significantly, the past is still remembered, and elements of traditional rites are sometimes reenacted during celebrations. In traditional Marind society, each clan and subclan was linked to a set of natural and social phenomena essential to human life. Organized into the Geb-zé and Sami-rek moieties, these kin groups formed a system of dual oppositions in which each moiety took precedence in different domains. A moiety is one part of something that is divided. [Source: J. Van Baal, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

The Geb-zé moiety was associated with male sexuality, ritual homosexuality, the sun and moon, travel eastward with the southeast monsoon, daytime, life, dry land and beaches, the coconut, the stork, and the cassowary. Its members presided over the major cults. The Sami-rek moiety was linked to female sexuality, heterosexuality, the underworld, travel westward with the northwest monsoon, night, death, the sea, swamps and inland areas, the sago palm, the dog, crocodile, and pig. Members of this moiety led head-hunting expeditions and the great feasts that followed them.

All kin groups had special links to the opposite moiety, based on traditional myths. This created a system in which the basic division between the two moieties appeared again and again in smaller parts of society. The main mythic figures were the dema, the ancestral beings of each clan. They played key roles in major ceremonies and were called upon in magic and everyday rituals. These invocations were considered strongest when spoken by someone from the clan descended from that particular dema. Because of this system, religious life depended on cooperation among the different subtribes within each settlement.

Major Rituals of the great cults functioned as initiation ceremonies tied to rebirth and the renewal of life. Mythic history was dramatized, and its central themes symbolically enacted. Of particular importance was the origin myth, shaped around two key motifs: the antagonism between the sexes and the idea that life arises from death. While the myth explicitly affirms male superiority, it also symbolically acknowledges women as the true source of life, for they give birth to the sun-bird. The life-from-death motif appears in the coconut—representing a human head—which sprouts when buried, and in the headhunting that followed initiation rites. In the Mayo Marind tradition, ritual emphasis falls on the female, while the Imo rites highlight a related but distinct theme: the link between the female principle, death, and decay, and the celebration of male success in warfare. Information on the cults of the Kondo and Upper Bian groups remains incomplete.

Death and the dead traditionally held relatively little significance in most Marind communities, except among the Upper Bian, where the deceased have been identified with the dema. The dead are believed to travel underground to the far east, where—like the sun—they emerge, journey westward, and pass beyond the sunset into the land of the dead. They may return to sit apart during great feasts, but they play no ongoing role in the affairs of the living.

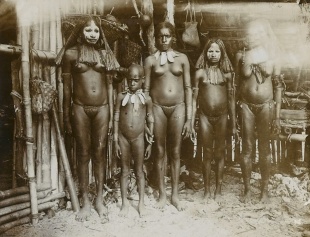

Marind Family and Gender

Men and women have traditionally lived largely separate lives, and men were not allowed to stay long in their wives’ houses. Even so, the women’s houses stand so close to the men’s house that conversations can easily be overheard on both sides. Women do most of the daily work and supply much of the food, but they have no authority in major rituals, although they take part in smaller ones. Girls are initiated into the Mayo fertility cult at about the same age boys begin their own rituals. Women sometimes hold their own ceremonial dances, modeled on the elaborate dances performed by men. Girls also pass through a sequence of age grades, but theirs carry less social importance. Land, gardens, trees, and men’s ornaments and tools are inherited through the father’s line, while women’s ornaments and belongings are inherited through the mother’s line. [Source: J. Van Baal, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Girls grow up mostly on their own, while boys are thought to need closer guidance. When young, boys sleep with their fathers in the men’s house. As they approach puberty, they are no longer allowed to stay in the village or on the beach during the day. Instead, they are placed under the care of a mentor—usually their mother’s brother—and sleep in his men’s house. For three to four years they live in strict seclusion until they move into a higher age grade that allows more freedom. This transition is marked by an exchange of gifts between the boy’s parents and his mentor. Another exchange of gifts takes place when, at age 18 or older, the young man returns to his father’s men’s house and soon prepares for marriage.

Marriage: Sister exchange is the preferred form of marriage, though first-cousin marriage is forbidden. In many inland groups, the exchange partners must be actual brothers and sisters, which sometimes leads families to adopt a child to create the needed pairing. Elsewhere, classificatory “siblingship” is enough, and even that rule may be relaxed, since the wishes of the couple are sometimes considered. First marriages are usually between people of the same age, and polygyny is uncommon. Traditionally, most marriages were stable and long-lasting, despite certain customs that might seem to threaten marital stability—such as wives’ participation in ritualized group sex and husbands’ ritual homosexual relations with their sisters’ adolescent sons.

Marind Sexuality

The Marind are also known for their distinctive sexual customs. One practice, otiv-bombari (ritual intercourse), took place on a girl’s wedding day. After the ceremony, the bride had sexual relations with her husband’s male relatives before joining her husband. Similar ritual intercourse could also occur at other important moments, such as after childbirth. The Marind were additionally known for a formalized tradition of ritual homosexuality. In their moiety system, the Geb-zé moiety was linked with male sexuality and homosexual practices, while the Sami-rek moiety was associated with female sexuality and heterosexual relations.

According to “Growing Up Sexually”: Van Baal (1966) observed that the Marind freely accept sex play of children. Sexual segregation starts at 4-5 to 7-8 years, and is strict by the time of pubertal onset. Boys go to the gotad (boy’s house), where masturbation and homosexual interaction with age-mates and a male mentor (binahor-evai) may occur. Homosexual practices are rumoured to take place at ceremonies and known to take place at special occasions as well. Girls are likewise assigned to a mentor, but no homosexuality was reported. [Source:“Growing Up Sexually. Volume I” by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas. 0.2 ed. 2004. Berlin: Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology, Berlin, October 2004; “Archive of Sexuality”, sexarchive.info ]

Boys underwent a kind of initiation during their adolescence. Anal intercourse among the Marind tribes was begun between the ages of seven and fourteen years, with the average being 10, when the boy was called patur. During their adolesence they were regarded as novices and referred to as wokravĭd, until they became éwati and, later, miakim. The wokravĭd was mockingly named “a girl”. Heterosexual intercourse was forbidden to the novices until it occurs ceremonially when among during the Majo part of the initiation. According to Berkhout and Wirz however, every éwati has his affairs with wahukus [roughly, ages 13-16, pubescent] or kivasom iwages.

Marind Life, Villages and Economic Activity

Sago is the staple food of the Marind, complemented by coconuts, bananas, and the products of hunting and fishing. On festive occasions they also eat pork from domesticated pigs, along with taro and yams grown either in raised coastal garden beds or in forest clearings inland. These gardens are likewise used for bananas and for cultivating kava, a favored stimulant alongside betel and, more recently, tobacco. [Source: J. Van Baal, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Most daily work falls to women: household tasks, planting, weeding, harvesting, processing sago, and gathering small fish and shellfish. Men hunt, do some fishing, build garden beds, and clear forest plots. They also make canoes, construct fences, and build the frames of houses, but their primary responsibilities lie in ritual and warfare.

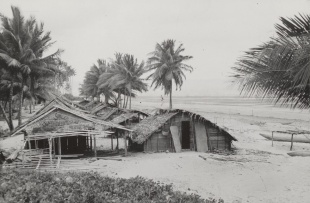

In the interior, the scattered distribution of sago groves results in dispersed settlements, rarely larger than 50–60 people. Coastal areas provide more favorable conditions—sandy ridges support coconut palms, and swampy areas behind them are suitable for sago—allowing for villages of up to 200 residents. Each village contains subclans from all four kinship groups, with each subclan occupying its own ward. Every ward includes several men’s houses, with one or two women’s houses situated nearby. A men’s house typically accommodates six or seven lineage-related men and an occasional relative. On the outskirts of the settlement stand daytime shelters used by boys and adolescent males. Houses are simple huts arranged in one or two irregular rows; where two rows exist, they run parallel with an open central space.

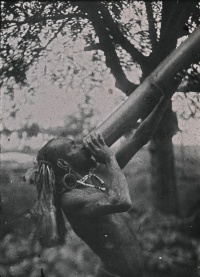

The Marind excel in body decoration, and their dances and ceremonies are visually striking. Decoration of objects is less emphasized, except for carved ceremonial spears and certain images used in Mayo initiation rites. Singing, accompanied by drumming, is important in both ritual and recreational contexts. Illness is treated by shamans, whose healing focuses on extracting harmful objects believed to have been magically inserted by hostile sorcerers. Many shamans are deeply knowledgeable about mythology and play significant roles in ritual life.

Traditionally, the Marind lived at a Stone Age level of technology, maintaining a largely self-sufficient economy. The main exceptions were stone tools—such as axe blades and club heads—which were obtained through trade with highland groups. Each subtribe’s territory and fishing grounds are allocated among the major clans. Gardens and planted trees are owned by individuals and inherited patrilineally.

Marind Politic Organization

The Marind traditionally had no centralized political system, but people still shared a strong sense of belonging. This unity was expressed through the use of shared superclan names, found throughout Marind territory. An even stronger source of solidarity came from participation in the great cults. The Imo cult, practiced by several inland subtribes and a few coastal communities, recognized a form of central leadership based on the coast. The Mayo cult—the largest and most influential—had no central authority. Originating in the far eastern coastal region, it spread all along the coast. Each subtribe held its own initiation rites every four years, lasting six to nine months. The celebrations moved west to east across the coast over a four-year cycle, with different regions taking their turn each year. [Source: J. Van Baal, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996]

Social control was mostly informal. Aside from the leader of the Imo cult, there were no official authorities except for the senior men in the men’s houses. Their influence depended largely on age and personal strength of character. A more powerful form of control was the widespread fear of sorcery, which anyone could commission against someone they disliked.

Conflicts over issues such as women or garden land were usually settled if the disputing parties lived in the same community. When problems remained unresolved, resentment could linger and might later resurface when an accidental death occurred, often leading to suspicions of sorcery. These suspicions reinforced the mistrust between subtribes. Accusations of sorcery frequently sparked violent fights and bloodshed, although beheadings did not occur. Ultimately, community pressure helped restore peace.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996, National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated November 2025