ASMAT ART

Asmat art has long been prized by European and American collectors. Interest surged in the 1960s, when pacification efforts ended warfare and headhunting—activities closely linked to the creation of many traditional objects. With these practices curtailed, the production of ritual artifacts declined. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has a first-rate collection of Asmat art, the majority of which was collected in 1961 by Michael C. Rockefeller. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

The best-known works come from the central and coastal Asmat regions, whose artists created decorated shields, spears, digging sticks, canoes, bows and arrows, and a wide variety of figurative carvings. Their most renowned ceremonial work is the bis—a towering ancestor pole carved and painted to honor those killed in battle or by sorcery. Bis poles were raised during feasts held before a retaliatory headhunting raid, and their designs often incorporated phallic symbolism.

Carl Hoffman wrote in “Savage Harvest”:“Expert woodcarvers in a land without stone, the Asmat crafted ornate shields, paddles, drums, canoes and ancestor poles, called bisj, embodying the spirit of an ancestor. The bisj poles were 20-foot-high masterpieces of stacked men interwoven with crocodiles and praying mantises and other symbols of headhunting. [Source: Carl Hoffman, Smithsonian Magazine, March 2014]

Motifs such as birds and flying foxes were common on shields and other objects because of their symbolic link to headhunting. In Asmat cosmology, humans and trees share a deep equivalence: a human head is metaphorically the “fruit” of a person, so animals that eat fruit are likened to warriors who take heads. The praying mantis also features prominently in Asmat sculpture.

The Asmat Museum of Culture and Progress collects artifacts from all areas of Asmat culture and produces catalogues and other publications on Asmat culture, mythology, and history. Located in the city of Agats in South Papua, it was conceived by the Catholic Crosier missionary Frank Trenkenschuh in 1969 as a way to preserve traditional Asmat art as well as provide economic outlets to the Asmat people.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ASMAT CULTURE: MUSIC, FOLKLORE, CEREMONIES, BODY ADORNMENT factsanddetails.com

ASMAT: HISTORY, RELIGION AND HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

ASMAT LIFE: SOCIETY, MARRIAGE, FOOD, VILLAGES, WORK factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI PEOPLE: HISTORY, CANNIBALISM, CONTACT WITH WESTERNERS factsanddetails.com

KOROWAI LIFE AND SOCIETY: RELIGION, FOOD AND TREEHOUSES factsanddetails.com

ASMAT AND KOROWAI COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN THE SOUTHERN LOWLANDS OF PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

MARIND PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (SOUTHWEST NEW GUINEA, INDONESIA) factsanddetails.com

KIMAM PEOPLE OF SOUTHERN PAPUA (WEST NEW GUINEA) factsanddetails.com

PAPUA — THE INDONESIA PART OF NEW GUINEA — NAMES, HISTORY, PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF PAPUA factsanddetails.com

PAPUA factsanddetails.com

FIRST PEOPLE IN NEW GUINEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

UNREST AND LIMITED AUTONOMY IN PAPUA SINCE THE OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998 factsanddetails.com

Asmat Art and Death

The Asmat honored their dead through elaborate feasts and rituals that both commemorated the deceased and reminded the community of the obligation to avenge their deaths. Central to these ceremonies were the towering bis poles—openwork carvings featuring stacked ancestor figures and a winglike projection symbolizing the pole’s phallus. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

In Asmat belief, no death occurred by chance; every death was caused by an enemy, whether through a headhunting raid or sorcery. Such loss created a spiritual imbalance that could only be corrected by taking an enemy head. When several members of a village had died, the community held a bis ceremony, a sequence of feasts lasting several months. Multiple bis poles were carved for the event and displayed in front of the men’s house, forming the focal point of a ritual mock battle between men and women.

The poles remained in place until a successful headhunt restored social balance. After a concluding feast, the Asmat carried the bis poles into the surrounding sago groves—the source of their staple food—and left them there to decay. As they returned to the earth, the poles were believed to release their fertile supernatural power, nourishing the sago trees and renewing the land.

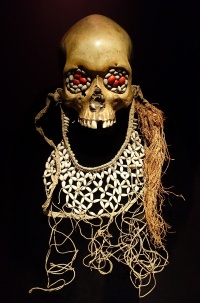

When an important person dies the body is wrapped and left on a platform until it completely decomposes. The skull is inherited by the oldest male child, who keeps it closes, sometimes using it as a pillow when sleeping or carrying it on his back or chest during the day. Asmat warriors sometimes cover their face with an ancestor’s skull decorated with a large shell nosepiece. During the jiape festival a dancer dons a fiber costumes representing the spirit of a deceased friend or relative. The event marks the passage of the dead to the spirit world . The dancer visits the home of the deceased where he is welcomed by the grieving family. At dawn, after dancing all night, the spirit dancer goes to a mangrove forest, symbolizing the realm of the dead.

Carl Hoffman wrote in “Savage Harvest”: Bisj “poles were haunting, expressive, alive, and each carried an ancestor’s name. The carvings were memorial signs to the dead, and to the living, that their deaths had not been forgotten, that the responsibility to avenge them was still alive. The completion of a bisj pole usually unleashed a new round of raids; revenge was taken and balance restored, new heads obtained — new seeds to nourish the growth of boys into men — and the blood of the victims rubbed into the pole. The spirit in the pole was made complete. The villagers then engaged in sex, and the poles were left to rot in the sago fields, fertilizing the sago and completing the cycle. [Source: Carl Hoffman, Smithsonian Magazine, March 2014]

Asmat Woodcarving

Asmat are skilled woodcarvers and their carvings are sought by collectors around the world. Their art includes canoe prows, bis poles, tall battle shields covered with praying mantises and other headhunting symbols. Modern pieces show families collecting sago or fishing. To the Asmat, woodcarving is inextricably linked with the spirit world, and therefore, is not necessarily considered an aesthetic craft. Much of the highly original art of the Asmat is symbolic of warfare, headhunting, and warrior-ancestor veneration. For centuries the Asmat, preoccupied with the necessity of appeasing ancestral spirits, produced a wealth of superbly designed shields, canoes, sculptured figures, and drums. Many of these masterpieces are today on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Source: Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia]

Emily Caglayan of the University of New York wrote: “ Wood carving is a flourishing tradition among the Asmat, and wood carvers are held in high esteem. The culture hero Fumeripits is considered to be the very first wood carver, and all subsequent wood carvers (known as wowipits) have an obligation to continue his work. The Asmat also believe that there is a close relationship between humans and trees, and recognize wood as the source of life. [Source: Emily Caglayan, Ph.D., Department of Art History, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art ]

“According to the Asmat origin myth, Fumeripits was the first being to exist on earth, and he also created the first men's ceremonial house, or jeu (a club house for men where community issues are discussed, artwork is made, and ceremonies are held). Fumeripits would spend his days dancing along the beach, but after awhile grew tired of being alone. So, he chopped down a number of trees, carved them into human figures, and placed them inside the jeu. However, since the sculptures were inanimate, Fumeripits was still unhappy. He then decided to create a drum, and chopped down another tree, hollowed out the center, and stretched a piece of lizard skin over the top. As he began to play the drum, the human figures miraculously came to life, their elbows came unstuck from their knees, and they began to dance.

“Like Fumeripits, present-day Asmat have a strong tradition of carving figural sculpture out of wood. These figures, which are representations of ancestors, are traditionally displayed inside the men's ceremonial house. Although these sculptures commemorate specific individuals who have died, they are not direct portraits, and have generalized features and similar body types. A common pose for these ancestral figures is the elbows-to-knees position (or wenet pose), believed to be the same pose that all humans assume at birth and again at death.

“Ancestral imagery also appears on other forms of Asmat art, including wooden war shields. Shields were created as functional items for warfare, and were meant to protect the user from the spears and arrows of his enemy. At the same time, the imagery that is carved and painted on the surface of the shield endows the piece with the power of the ancestors, which is also intended to protect the user. The designs can be either figural or abstract, depending on the region from which the shield came.

“Bis poles are perhaps the most impressive works of art by the Asmat, reaching heights of up to twenty feet. These poles are carved to commemorate the lives of important individuals (usually warriors), and serve as a promise that their deaths will be avenged. These works also assist in the transport of the souls of the dead to the realm of the ancestors. The mangrove tree, from which the sculptures are created, is actually turned upside down and a single planklike root is preserved (which will ultimately project from the top of the artwork). The imagery on the pole itself varies, but usually includes a series of stacked ancestral figures. In interior Asmat villages, wuramon, or spirit canoes (1979.206.1558), serve a similar function.

“Asmat body masks are full-length costumes made of plaited cordage composed of rattan, bark, and sago leaf fiber. The body masks are usually painted with red and white pigment, decorated with carved facial features, and given skirts made of sago leaves. The end result depicts an otherworldly being, which appears only for special funerary ceremonies, known as jipae.”

Today, the annual Asmat Woodcarving Festival—held each October—supports the continuation of traditional woodcarving. Works are judged, and the winning piece is placed on permanent display in the Asmat Museum of Culture and Progress in Agats. Other carvings, including bis poles, are auctioned during the festival.

Asmat Decorated Bowls and Everyday Objects

Asmat woodcarvers decorated virtually everything they created, from sacred ceremonial images to the mundane objects from everyday life. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a painted wooden bowl that is 90.2 centimeters (inches) and was made in Erma village on the Pomatsj River on the southwest coast of New Guinea in early to mid-20th century. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Eric Kjellgren wrote: This deep, elegantly shaped vessel, with sides carved to a delicate, almost weightless thinness, was an ordinary food bowl used for serving sago. The bowl is carved in the form of a miniature canoe adorned, like its larger counterparts, with a carved "prow." The finely rendered geometric designs that run along the rim are also identical to those that decorate the gunwales of actual canoes. The prow depicts the stylized head of a black king cockatoo (ufir), recognizable by its sharp, curving beak and prominent bulbous tongue. Humans, in Asmat religion, were metaphorically identified with trees, whose fruit was symbolic of human heads.

Asmat warriors in the past took the heads of their victims; consequently creatures such as black king cockatoos, hornbills, and ftying foxes (large fruit bats), which plucked the fruit of trees were methaphorically associated with headhunting. Images of frugivorous animals appear widely as head-hunting symbols in Asmat art. However, their forms are often stylized, almost to the point of abstraction. While the head of the black king cockatoo is portrayed here in a relatively naturalistic fashion, in other works it is reduced to a single C-shaped motif representing the cockatoo's beak, with a small protuberance in the center to indicate the bird's distinctive tongue.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection is also has a sago pounder made of wood, bamboo, fiber, by an artist named Zoap in mid-20th century. It is 91.4 centimeters (36 inches) long was made in Sauwa village on the Pomatsj River. Another sago pounder was made by the Asmat from wood, bamboo, fiber by an artist named Sep. It is 85.7 centimeters (33.75 inches) long and was made in Tomor (Tjemor) village on the Unir (Undir) River A Sago Platter (Bewar) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was made in the mid-20th century of wood, bamboo. It originates Otsjanep village, Ewta River and measures 69.5 × 24.4 × 8.3 centimeters (27.4 inches high, with a width of 9.6 inches and a depth of 3.25 inches).

Asmat Daggers and Shields

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Before the gradual pacification of western New Guinea (modern Papua) under Dutch colonial authority in the 1950s, Asmat warriors carried a variety of weapons. Together with spears, shields, and bows and arrows, an Asmat man 's armaments included daggers, which were used both in active combat and in the ritual slaying of enemies. Living in a region of vast muddy swamps, where even stone was unavailable except through trade, the Asmat valued bone for its strength and durability, which made it an ideal material for daggers. The bone for Asmat daggers was derived from several sources. The weapons were typically made from the leg bones of humans or cassowaries. Each type had a separate name: daggers made from human bones were called ndam pisuwe, whereas cassowary-bone examples were known as pi pisuwe. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

One Ndam pisuwe dagger in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection comes from the southwest coast of New Guinea and was made in the early to mid-20th century from bone, fiber, feathers and seeds. It is 33.7 centimeters long (13.3 inches) long and is adorned with openwork carvings depicting stylized human images, whose long, slender bodies and sharply flexed limbs evoke the form of a praying mantis, a creature symbolically associated with headhunting. In some instances artists used the jawbones of crocodiles to create massive bone daggers known as eu karowan, the largest such weapons produced by any New Guinea people. The pommels of Asmat daggers were often lavishly embellished, encased in netlike coverings and hung with bushy tassels of black cassowary feathers, accented by colored seeds. A conspicuous element of a warrior's raiment, a decorated dagger was often worn inserted into a fiber armband on the upper arm as a symbol of its owner's prestige and martial prowess.

Asmat shields are among the most iconic works of Asmat warriors and woodcarvers, traditionally used in warfare and decorated with bold, symbolic designs. The Metropolitan Museum of Art holds several mid-20th-century Asmat shields that highlight the diversity of regional carving traditions. One example is made of wood, paint, and sago palm leaves, and measuring 253.4 × 68.9 × 14 centimeters (99.75 × 27.12 × 5.5 inches). Additional shields include a piece by Sep from Tomor (Tjemor) village on the upper Unir (Undir) River, measuring 193 × 45.7 × 14 centimeters (76 × 18 × 5.5 inches); another by Pono from Momogo or Agani on a northern tributary of the Pomatsj River, measuring 148 × 43.8 × 5.7 centimeters (58.25 × 17.25 × 2.25 inches) and a shield by Jinum from Monu village on the upper Unir (Undir) River, measuring 219.7 × 55.9 × 11.4 centimeters (86.5 × 22 × 4.5 inches). Together, these works demonstrate the Asmat’s bold geometric carving, ancestral symbolism, and exceptional mastery of monumental woodwork.

Asmat Ancestor Figures

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Humans, trees, and wood sculpture are inseparably linked in the cosmology and art of the Asmat people, who live in the densely forested river swamps of the southwest coast of New Guinea. Humans are equated, both metaphorically and metaphysically, with trees, and each element of a tree has its counterpart with the human body, the roots being the legs and feet; the trunk, the torso; the branches, the arms and hands; and the fruit, the head. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

According to many Asmat origin traditions, human beings are descended from wood figures carved from trees by a primordial being named Fumeripits. After a series of adventures Fumeripits went into the forest, where he built the first men's house (yeu). Living in the empty house, Fumeripits became lonely, so he cut down trees in the forest and carved them into male and female human figures, which he placed in the yeu for company. The lifeless figures, however, did not relieve his loneliness, so he cut down anoth er tree, from which he fashioned a drum. As he started to play, the fi gures slowly began to come to life. At first, the figures, whose elbows and knees were joined together, moved awkwardly, but as the bonds between their limbs broke, they arose and began to dance and sing, becoming the first Asmat.

Following in the footsteps of their divine predecessor, Asmat master carvers, continue the tradition of fashioning human images from wood. Virtually all human images in Asmat art portray ancestors. The vast majority of Asmat ancestor images represent individuals who have recently died and formerly served as visual reminders to the living that those deaths, attributed to enemies' direct aggression or malevolent magic, needed to be avenged.

In most cases ancestor images appear as elements of more complex works, such as bis poles, shields, and other objects. Asmat carvers, however, also created freestanding ancestor figures, which played a role very similar to that of the primordial wood carvings. In some areas these independent figures were likely created for yeu pokmbu, the ceremonies celebrating the inauguration of a new men's house. The rites included not only the creation of wood figures but also the reenactment of the origin of humanity by performers dancing with wobbly knees to simulate the awkward movements of the first humans, whose elbows and knees had just been separated.

One ancestor figure in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection comes from Mu nu village on the Unir River. Made in the early to mid-20th century from wood, paint, fiber, shell, cassowary quills, it is 125.7 centimeters (49 inches) tall and depicts a recent ancestor, whose name would have been given and whose posture evokes that of the first human ancestors. The small tabs of wood that link the knees and elbows probably depict the bonds that connected the limbs of the primeval wood figures before they sprang fully to life. Thus, the figure is at once the image of a specific individual, who would have been well known to contemporary members of the community, and a representation of the genesis of humanity The gaunt body with its slender, bent limbs and bulbous head is also a visual reference to the form of a praying mantis. Among the Asmat, the praying mantis, whose females frequently behead the males during mating, was a potent symbol of head-hunting, the act through which in the past the death of the ancestor represented by the figure would ultimately be avenged.

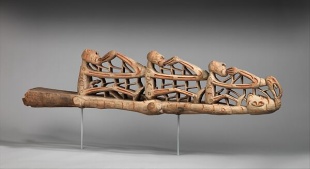

Asmat Spirit Canoes

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Created in only a handful of communities in the northwest Asmat region, spirit canoes (wuramon) are the largest of all Asmat sculpture, with some examples reaching nearly 12.5 meters (40 feet) in length. Despite their grand scale and the great labor invested in their production, wuramon are made for onetime use during the ceremony known as emak cem, "the bone-house feast." The complex sequence of rites involved in emak cem principally celebrates the spirits of the dead and the initiation of the young boys who will perpetuate the ways of the ancestors. During the ceremony the boys live in seclusion for several months in a specially constructed ritual house-the emak cem, from which the feast takes its name. As the end of the seclusion period approaches, carvers gather in the men's house, known locally asje, to create the wuramon. The wuramon takes the form of an enormous canoe, crewed by spirits who sit between its long, gently curving gunwales. A supernatural rather than an earthly vessel, the spirit canoe has no bottom, as the beings it carries do not require a complete hull for their travels. 5 Each of the spirit figures is created by a separate carver, whose work is 5, detail supervised and critiqued by a master artist. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The images have a dual nature and meaning. In their outer forms, the figures represent nonancestral beings — supernatural creatures whose bodies at times combine human and animal features. However, each of these fantastic figures is named for a specific, recently deceased ancestor, whose spirit it embodies and who, through the carving of the wuramon and the performance of the emak cem, is encouraged to bestow his life-giving powers on the community and to travel on to safan, the land of the dead.

The spirit images occur in a number of different forms, many of which can be seen in the present work. The figure of a turtle (mbu), as here, always appears at or near the center of the vessel. Able to carry and lay vast numbers of eggs, turtles are a potent symbol of fertility in Asmat cosmology. Behind the turtle is an image of an okom, a dangerous water spirit with a Z-shaped body that crawls along the bottoms of rivers and streams. The remaining figures, who sit crouched, gazing down through the bottomless hull, portray ambirak, dangerous water spirits often depicted with birds' heads, or other, humanlike spirits known as etsjo. Smaller birdlike figures, called the "ears" (ci yon wo) of the wuramon, appear at the stern and prow. In this case the prow itself takes the menacing form of a hammerhead shark.

One Asmat spirit canoe in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was created in the mid-20th century by the artist Ofo and originates from the Pomatsj River region (As-Atat). Carved from wood and painted, it is 3.83 meters (12.7 feet long). Another wuramon from the southwest coast—Utumbuwe River, Yamas village—also dates to the mid-20th century and reaches 8.7 meters (28.6 feet) in length.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection also contains Asmat canoe prows. One made by the artist Soro of Agani village on the northern tributary of the Pomatsj River in the mid-20th-century is made of wood and paint and measures 57.8 centimeters (22.75 inches). Also from Agani village, artist Boti carved this painted wooden prow, measuring 70.5 centimeters (27.75 inches). One carved by Osu of Erma, Pomatsj River region measures 149.9 × 25.4 × 34.3 centimeters (59 × 10 × 13.5 inches).

Bisj Poles

The most spectacular of all Asmat sculptures are the towering ancestor bis poles,which can reach heights of up to 7.7 meters (25 feet). Within the Asmat region, bis poles were, and to some extent still are, made only in a comparatively small region of the central Casuarina coast by a subgroup known as the Bisman (literally, "carvers of bis") and some of their neighbors. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Bis poles look a little like totem poles and have traditionally erected in front of ceremonial houses. Each one is carved from a tree trunk to represent two villagers killed during a headhunting raid. Stone and shell tools were originally used to carve them but these have been replaced by steel tools. Bis poles often have phallic extensions at top and are regard by many Westerners as magnificent works of art with “exuberance for form, shape and color.”

Bisj poles are made by the Asmat to remind themselves of ancestors whose deaths that needed to be avenged. To drive off evil spirits after a bis-pole carving session, Asmat women sometimes greeted their men with spears and arrows and clubbed their husbands as they stepped ashore. Fumerptis, the god credited with creating the Asmat people, did so by bringing to life carved wooden figures.

In the 1970s, there weren't many “bis “poles left. Because of their association with headhunting the government outlawed them. In the old days villages used to have large numbers of them set up outside the ceremonial houses which indicated the numbers of victims taken in headhunting raids. Collectors pay around $400 a piece for them in 1970s. [Source: Malcolm Kirk, National Geographic, March 1972]

Bis Pole Ornamentation

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The human figures on the bis poles depict recent ancestors. Although the imagery is highly conventionalized, each figure represents and is named for a specific individual who has recently died. The images honor the memory of the deceased. In former times the poles also served as visual reminders to the living of the necessity of avenging their deaths. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

One bis pole in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection is made of wood, paint and fiber, Dating to the late 1950s, it originates from Omadesep village in the Faretsj River region and measures 5.5 × 1 × 1.6 meters (18 feet inches high, with a width of 39 inches and a depth of 63 inches). The figures on the bis anakat represent the individual (ideally, a warrior killed in battle) for whom the pole is named, together with other deceased relatives. 17 The orientation of the images in the bis anakat varies, with figures occasionally appearing upside down or facing backward. However, the unusual positions of the figures do not appear to carry any special significance. 18 Projecting from the abdomen of the uppermost figure, the cemen represents the phallus of the pole, a symbol of vitality and fertility.

The complex openwork designs are often purely geometric compositions, largely made up of motifs derived from stylized representations of animals or warriors' ornaments, all of which are symbolic of headhunting. On occasion, human heads, said to represent those of enemies captured by the deceased during his lifetime, or complete human figures, identified variously as images of deceased children or as the small wraithlike spirits of the dead, also appear within the cemen.

The lower section of the pole is composed of two parts, the ci (canoe), which, as here, is at times explicitly carved in the form of a miniature canoe, and the bino, the sharp, pointed portion of the base, which in some instances is inserted into the ground. The canoe serves as a supernatural vehicle in which the lingering spirits, appeased and liberated by the bis feast, and formerly, the ensuing raid, are conveyed to their final abode in safan, the realm of the dead.

Asmat Body Masks

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Asmat people create and use elaborate woven masks for ritual feasts that celebrate the passage of the recently deceased from the world of the living to the ancestral realm known as safan. Each body mask is a complex ensemble comprising a wealth of locally sourced materials including mulberry fiber, sago palm leaves, wood, bamboo, feathers and seeds. The torso and shoulders are constructed of rattan in a single rod coiled basketry technique. The fine fiber cord is then attached to the rattan waistband and the mask is gradually built up, using a delicate single element looping technique, to complete the chest and headpiece. The mask is then painted with red ochre and lime and the important appendages are added. The waistband and sleeves are adorned with lengths of sago palm leaves which form a rustling skirt and fringes which hang down over the arms.[Source: Evelyn A. J. Hall and John A. Friede, Associate Curator Oceanic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The mid-20th-century Asmat body masks in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection originate from several villages along the northern tributaries of the Pomatsj River, including Pupis and Momogo. Made from fiber, sago palm leaves, wood, bamboo, feathers, seeds, and paint, they represent large basketry-sculptures worn in performance and ritual. One mask from Pupis village measures 226.1 × 81.3 × 59.7 centimeters (89 × 32 × 23.5 inches) while two masks from Momogo village measure 206.4 × 68.6 × 50.8 centimeters (81.25 × 27 × 20 inches) and 182.9 centimeters (72 inches) respectively.

One particularly elaborate example has intricate and very finely executed fiber work in the striped cord bodice and head piece which is decorated with tassels comprising feathers and seeds, and topped off with a dramatic extension that reaches upwards. Dramatic wooden eye lozenges incorporated into the headpiece give the figure an imposing and lively character. These eye elements have been washed with a white lime and red ochre rim that highlights the black pupils and are embellished with black cassowary bird feathers.

One remarkable body mask was collected by Michael C. Rockefeller when he visited the Asmat region of New Guinea in 1961. He negotiated for it with clan leaders in the village of Pupis on the northern tributary of the Upper Pomatsj River. It is one of a set of seven that were made on the occasion of the construction of a new feast house in the village. In Asmat cosmology, when an individual dies their spirit (ndat) typically enters a state of limbo, a threshold between the human world and the ancestral realm safan. A restless spirit lingering near the community has the potential to cause misfortune or illness, so it is customary for its living relations to host a feast ceremony (jipae) that will assist the spirit in moving onward to the next stage of its journey. The precise details of these rites vary from place to place but in general all Asmat mask feasts share a common goal – to welcome the spirits of the dead briefly back to the community for a feast and celebration, after which the spirits are expected to permanently leave the world of the living. This serves as a way of restoring harmony to the community.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Peter Van Arsdale and Kathleen Van Arsdale, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1996; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Geographic,, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Encyclopedia.com, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2025