FOOT BINDING IN CHINA

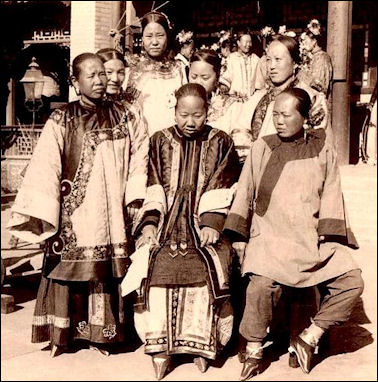

Foot binding among wealthy women Foot binding was performed on Chinese women for over one thousand years, through the 20th century. It required breaking the arch of the feet, and tying up the feet, causing them to curl up into stumps regarded as beautiful and sexually exciting to men. The process used to create bound feet was painful and uncomfortable. Once the job was complete women hobbled rather than walked around.

According to the Middle Ages Reference Library: “Men in premodern China believed that small feet on a woman were beautiful, and during the Sung dynasty years they developed a means to ensure that women's feet would remain small. In childhood, a Chinese girl would have her feet bound with strips of cloth, which constricted their growth. By the time she became a woman, she would have abnormally small feet, so much so that walking became difficult." For the most part "foot-binding only applied to women of the upper classes; peasant girls had to work in the fields, and tiny feet would only slow them down. Nor did the practice attract many admirers outside of China: though Chinese men swooned at the sight of tiny feet, Westerners thought them grotesque. In the modern era, foot-binding became a symbol of the hard-line conservatism that prevailed during imperial times, and the end of the monarchy in 1912 also saw the end of foot-binding. [Source: Middle Ages Reference Library, Gale Group, Inc., 2001]

Kit Gillet wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The practice of foot binding was prevalent across Chinese society, starting with the wealthier classes but over the years spreading down through urban and then poorer rural communities. The feet of girls as young as 5 would be broken and bound tightly with cotton strips, forcing their four smallest toes to gradually fold under the soles to create a so-called 3-inch golden lotus, once idealized as the epitome of beauty. The process would take many years and would lead to a lifetime of labored movement, as well as a regular need to rebind the feet. [Source: Kit Gillet, Los Angeles Times, April 16, 2012]

Amanda Foreman wrote in Smithsonian Magazine, “I balanced a pair of embroidered doll shoes in the palm of my hand as I talked about the origins of foot-binding. When it was over, I turned to the museum curator who had given me the shoes and made some comment about the silliness of using toy shoes. This was when I was informed that I had been holding the real thing. The miniature “doll” shoes had in fact been worn by a human. The shock of discovery was like being doused with a bucket of freezing water. As I held the lotus shoes in my hand, it was horrifying to realize that every aspect of women’s beauty was intimately bound up with pain. Placed side by side, the shoes were the length of my iPhone and less than a half-inch wider. My index finger was bigger than the “toe” of the shoe. It was obvious why the process had to begin in childhood when a girl was 5 or 6. [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 \~]

In the imperial era bound feet were regarded as the epitome of feminine beauty and an indication of nobility. In the Communist era, the custom was looked down as a primitive vestige of the feudal era: its beauty defined by backward men. Gillet wrote: “Now the ancient, some say barbaric, practice is almost gone. The practice fell out of favor at the turn of the 20th century, viewed as an antiquated and shameful part of imperialist Chinese culture, and was officially banned soon after. But in rural areas, the feet of some young girls were still being bound into the early 1950s. Only a few are still alive. Although people in the West regard foot binding as primitive. Western women did awful things to their feet too: they wore shoes that were too small to make their feet look tiny and put on high heels. In the story of Cinderella, the ugly step sisters mutilated their feet to fit into the glass slipper.

See Separate Articles:CHINESE WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; TIGER MOTHER AMY CHUA factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WOMEN AND DRAGON LADIES IN CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; HARD LIFE OF WOMEN IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN UNDER COMMUNISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN TRAFFICKING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE FAMILY factsanddetails.com ; BEAUTY IN CHINA: FACE SHAPE, WHITE SKIN AND PAGEANTS factsanddetails.com ; HAIR AND HAIRSTYLES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CLOTHES IN CHINA: MAO-ERA FASHIONS, SLIT PANTS AND DAYTIME PAJAMA-WEARING factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CLOTHES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FASHION IN CHINA: WESTERN BRANDS, FOREIGN DESIGNERS AND HAN CLOTHING factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FASHION DESIGNERS factsanddetails.com ; COSMETICS, TATTOOS AND JEWELRY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; COSMETIC SURGERY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOUR BEAUTIES OF ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com ; FOOT BINDING AND SELF-COMBED WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ASIAN PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Women in China Sources fordham.edu/halsall ; Chinese Government Site on Women, All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) Women of China ; Human Trafficking Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery in China gvnet.com ; International Labor Organization ilo.org/public Foot Binding San Francisco Museum sfmuseum.org ; Angelfire angelfire.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia Pam Cooper of Northwest University is an expert of foot-binding.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Bound Feet, Young Hands: Tracking the Demise of Footbinding in Village China by Laurel Bossen and Hill Gates Amazon.com; “Ties that Bind, Ties that Break” by Lensey Namioka (1999) Amazon.com; “Aching for Beauty: Footbinding in China” by Wang Ping (2000), an account of foot binding and fetishism. Amazon.com; “Splendid Slippers” by Beverley Jackson(1997) Amazon.com; “Cinderella's Sisters” by Dorothy Y Ko (2005) Amazon.com

Origin of Foot Binding

Foot binding shoes It is not clear exactly when foot binding began. The custom is believed to have originated between the Tang and Song dynasties. Tenth century descriptions of “golden lotuses” in the royal courts are thought to be references to bound feet. According to one story foot binding was invented by a palace dancer who indulged the aesthetic whim of her royal master. According to another story it began after an emperor became enchanted with a women with small feet who danced on top of a lotus-shaped platform.

Amanda Foreman wrote in Smithsonian Magazine, “Foot-binding is said to have been inspired by a tenth-century court dancer named Yao Niang who bound her feet into the shape of a new moon. She entranced Emperor Li Yu by dancing on her toes inside a six-foot golden lotus festooned with ribbons and precious stones. Some early evidence for it comes from the tomb of Lady Huang Sheng, the wife of an imperial clansman, who died in 1243. Archaeologists discovered tiny, misshapen feet that had been wrapped in gauze and placed inside specially shaped “lotus shoes.” [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 \~]

“Earlier forms of Confucianism had stressed filial piety, duty and learning. The form that developed during the Song era, Neo-Confucianism, was the closest China had to a state religion. It stressed the indivisibility of social harmony, moral orthodoxy and ritualized behavior. For women, Neo-Confucianism placed extra emphasis on chastity, obedience and diligence. A good wife should have no desire other than to serve her husband, no ambition other than to produce a son, and no interest beyond subjugating herself to her husband’s family—meaning, among other things, she must never remarry if widowed. Every Confucian primer on moral female behavior included examples of women who were prepared to die or suffer mutilation to prove their commitment to the “Way of the Sages.” The act of foot-binding—the pain involved and the physical limitations it created—became a woman’s daily demonstration of her own commitment to Confucian values. \~\

History of Foot Binding

Joshua Wickerham wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender” “Though references to beautiful women with small feet are almost as old as written history, foot binding is generally agreed to have emerged in the Northern Song (960-1127) and moved south during the Southern Song (1127-1279). It became widespread during the Ming Dynasty and peaked in the Qing. Even though Chinese literati first railed against this practice in the seventeenth century, it survived well into the Republican period with popular phrases like, "If you love your son, you don't go easy on his studies. If you love your daughter, you don't go easy on her foot binding." “For elite families, these tiny "golden lotus feet" were permanent symbols of their lives of leisure. For lower families, feet lent rank and gentility to a daughter otherwise without chance of raising her social standing. [Source: Joshua Wickerham, “Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Culture Society History”, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Amanda Foreman wrote in Smithsonian Magazine, ““Foot-binding, which started out as a fashionable impulse, became an expression of Han identity after the Mongols invaded China in 1279. The fact that it was only performed by Chinese women turned the practice into a kind of shorthand for ethnic pride. Periodic attempts to ban it, as the Manchus tried in the 17th century, were never about foot-binding itself but what it symbolized. To the Chinese, the practice was daily proof of their cultural superiority to the uncouth barbarians who ruled them. It became, like Confucianism, another point of difference between the Han and the rest of the world. Ironically, although Confucian scholars had originally condemned foot-binding as frivolous, a woman’s adherence to both became conflated as a single act. [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 \~]

“The truth, no matter how unpalatable, is that foot-binding was experienced, perpetuated and administered by women. Though utterly rejected in China now it survived for a thousand years in part because of women’s emotional investment in the practice. The lotus shoe is a reminder that the history of women did not follow a straight line from misery to progress, nor is it merely a scroll of patriarchy writ large. Shangguan, Li and Liang had few peers in Europe in their own time. But with the advent of foot-binding, their spiritual descendants were in the West. Meanwhile, for the next 1,000 years, Chinese women directed their energies and talents toward achieving a three-inch version of physical perfection.” \~\

The Mongols outlawed foot binding in 1279. The custom was banned several times in the Qing Dynasty, the last time when the dynasty collapsed in 1911 but the last shoe factory making lotus shoes didn't close until 1999. In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”:“The practice of binding the feet of Chinese girls is familiar to all who have the smallest knowledge of China, and requires but the barest mention. It is almost universal throughout China, yet with some conspicuous exceptions, as among the Hakkas of the south, an exception for which it is not easy to account. The custom forcibly illustrates some of the innate traits of Chinese character, especially the readiness to endure great and prolonged suffering in attaining to a standard, merely for the sake of appearances. There is no other non-religious custom peculiar to the Chinese which is so utterly opposed to the natural instincts of mankind, and yet which is at the same time so dear to the Chinese, and which would be given up with more reluctance. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

“It is well known that the greatest emperor who ever sat upon the throne of China dared not risk his authority in an attempt to put down this custom, although his father had successfully imposed upon the Chinese race the wearing of the queue as a badge of subjection. A quarter of a millennium of Tartar rule seems to have done absolutely nothing toward modifying the practice of foot-binding in favor of the more rational one of the governing race, except to a limited extent in the capital itself. But a few li away from Peking, the old habits hold their iron sway. The only impulse toward reform of this useless and cruel custom originated with foreigners in China, and was long in making itself felt, which it is now, especially in the central part of the empire, beginning to be.

Bound feet

Women Who Underwent Foot Binding

No man it was said could resist the delicateness and vulnerability of young girl with tiny, pointed feet. On an 83-year-old woman with bound feet in 2006, Jim Yardley wrote in New York Times:Mrs. Wang said she was married at 15. Asked about her feet, she laughed, slipped off a blue, canvas slipper and flapped the top half of her stunted foot back and forth like a swinging door. “My feet were wrapped when I was 5 years old, ” she said. “No one wanted you unless you bound your feet. That is what my mother told me. A woman with very small feet was considered a very desirable wife...They don’t peel and they don’t hurt, but the bone is broken.” By 1933, she said, the Communists took control of the Shenmu region and forbade old customs like bound feet. “When I was 12, they were unwrapped, ” she recalled, explaining why her feet are slightly larger than those of other women of her generation. “When Chairman Mao came around, binding feet wasn’t allowed anymore.” [Source: Jim Yardley, New York Times, December 2, 2006]

Amanda Foreman wrote in Smithsonian Magazine, “From the start, foot-binding was imbued with erotic overtones. Gradually, other court ladies—with money, time and a void to fill—took up foot-binding, making it a status symbol among the elite. A small foot in China, no different from a tiny waist in Victorian England, represented the height of female refinement. For families with marriageable daughters, foot size translated into its own form of currency and a means of achieving upward mobility. The most desirable bride possessed a three-inch foot, known as a “golden lotus.” It was respectable to have four-inch feet—a silver lotus—but feet five inches or longer were dismissed as iron lotuses. The marriage prospects for such a girl were dim indeed.” \~\ [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 \~]

Not all upper class women practiced foot binding. The Manchu Qing rulers forbid it among Manchu women. Most ethnic minorities in China did not practice it. After it was banned for good by the Communists, Chinese women with bound feet were humiliated and became the objects of derision. One woman told the Los Angeles Times, “I was a child and had no control when my feet were bound, and I had no control when I was told to unbind them.” “Foot binding was also a strong multi-generational tie for women, with the procedure performed by the women in a family. "It was a strong tradition passed from mother to daughters, entangled with shoemaking, how to endure pain and how to attract men. In many ways, it underpinned women's culture," Dorothy Ko, a history professor at Barnard College in New York, told the scholars. She is the author of "Cinderella's Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding." "It is hard to romanticize the practice and I am happy to see it go, but it is a pity there is no comparable, but obviously less painful, practice to take its place and bond generations," Ko says.

Foot Binding Process

Binding the feet was done with cloth, and began when a girl was four, five or six. The bandages were not supposed to be removed, except for periodic washing, until the girl was married. According to one custom the stinky bandages were removed on her wedding night, when her new husband indulged himself by drinking alcohol from them.

Joshua Wickerham wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender” Between the ages of five and seven, girls underwent the painful procedure of having their small toes broken and bent under the foot to the heel and their feet wrapped. For these two years, they were forced into smaller and smaller "golden slippers," dancing and jumping on their feet to get them to the standard three inches or smaller. This impeded their ability to walk and work. [Source: Joshua Wickerham, “Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Culture Society History”, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Amanda Foreman wrote in Smithsonian Magazine, “First, her feet were plunged into hot water and her toenails clipped short. Then the feet were massaged and oiled before all the toes, except the big toes, were broken and bound flat against the sole, making a triangle shape. Next, her arch was strained as the foot was bent double. Finally, the feet were bound in place using a silk strip measuring ten feet long and two inches wide. These wrappings were briefly removed every two days to prevent blood and pus from infecting the foot. Sometimes “excess” flesh was cut away or encouraged to rot. The girls were forced to walk long distances in order to hasten the breaking of their arches. Over time the wrappings became tighter and the shoes smaller as the heel and sole were crushed together. After two years the process was complete, creating a deep cleft that could hold a coin in place. Once a foot had been crushed and bound, the shape could not be reversed without a woman undergoing the same pain all over again. [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 \~]

The binding stunted foot growth and caused bones in the arch to break, the toes to curl under the foot, and the foot to bend and scrunch together. The bandages bent down the four small toes towards the sole of the foot and forced the heel inward, exaggerating the arch. The process was very painful. Flesh rotted. Infections added to the pain of the process itself.. Girls wept and moaned and often had difficultly sleeping and even eating or drinking because the pain was so intense.

Attractions of Foot Binding

Describing the "exquisite feet" of concubine in a story, one 15th century writer wrote they are "three inches long and no wider than a thumb." A 13th century poet wrote: "Why must the foot be bound?/ To prevent the barbarous running around." A 17th century writer said, "If [girls'] feet are not bound, they go here and there with unfitting associates."

Yang Yang, a Yunnan resident and author two books on foot binding, told the Los Angeles Times, "In ancient China, men preferred women with small feet, and in a male-dominated society where the best a woman could do was marry well, the reality was that what men wanted, men got," he says. The 17th century Spaniard Domingo Navarrete praised foot-binding as "very good for keeping females at home. It were no small benefit to them and their menfolk if it were also practiced everywhere else too."

"The mincing gait of these maidens, who could not stray beyond the limits of their room, bewitches men, young an old alike,” Pang-Mei Natasha Chang wrote in “Bound Feet and Western Dress”. “He who beat out all others in a drinking game downed his last from one tiny embroidered slipper whose owner lay waiting for him on the top floor of the teahouse.” Later upstairs, “In the intimacy of her chamber, she would unravel the bindings of her feet and reveal them to him. That evening, in a final moment of passion, he would lift her tiny unwrapped feet to his shoulders and thrust them into his mouth to suck."

Among upper class women, foot binding was regarded as a prerequisite to getting married, with mothers passing on the custom to their daughters. Chinese couldn’t understand how any man could marry a woman with big ugly feet. One 78-year-old woman with bound feet told the Los Angeles Times, “of course it was painful. If you didn’t bind your feet, you couldn’t find a husband.”

Restrictions of Foot Binding

Bound feet, known as "lily feet" or tiny "lotus feet," sometimes were only three or four inches long. They resembled hooves or "fists of flesh." The pointed toes could be flapped back and forth like a swinging door against the top half of the feet. Because foot-bound women couldn't do physical labor, travel around or move around much, only high class women could afford to have it done. Hard-working, lower-class women needed normal feet to do their chores and fullfill their duties.

Foot binding greatly restricted the lives of women who had it done to them. It was difficult to walk, let alone run or dance with bound feet. Footbound women it was said walked with "a stylized, mincing gait.” When they dressed in robes their movements reminded some of lotuses blowing in the wind. They often wore tiny shoes or silk embroidered slippers that were generally around 2½ inches wide and five to seven inches in length. The first high heels were designed for bound feet.

Amanda Foreman wrote in Smithsonian Magazine,“In addition to altering the shape of the foot, the practice also produced a particular sort of gait that relied on the thigh and buttock muscles for support. [Source: Amanda Foreman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2015 \~]

Food Binding Today

Hardly any women have bound feet any more. Most that do are in their 80s and 90s and they are dying off every year. Foot binding hasn’t been done since the Communists came to power in 1949, except possibly in some remote rural areas.

In the mid-1990s, a village with 300 elderly women with bound feet was found in Yunnan Province. The discovery made headlines and stories were written on how the women played croquet and danced.

Only one factory, the Zhiqiang Shoe Factory in Harbin, continues to make shoes for bound feet. Many of them are sold as souvenirs rather than as footwear. The shoes that are still worn are generally plain looking because the women who wear them do not want to draw attention to their feet.

A study published in 1997 in the American Journal of Public Health found that women with bound feet were more likely have hip or spinal fractures.

Foot Binding Slowly Slips into History

In the village of Liuyi in Yunnan China there were about 30 women left who have bound feet as of 2012. Reporting from there, Kit Gillet wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Bathed in a faint afternoon sunlight that seems to highlight every wrinkle on her face and hands, Fu Huiying hobbles around her dusty home. Nearby, chopped vegetables suggest a dinner half-made, and the smoke of years of cooking has stained the wall behind a small gas stove. But the eyes are drawn to Fu's deformed feet and the tiny, ornate shoes on the floor next to her, both objects marking the 76-year-old as one of the last of a kind. [Source: Kit Gillet, Los Angeles Times, April 16, 2012]

“Isolated from the country's key cultural and administrative hubs, the area around Liuyi, a village of about 2,000 people in southern China's Yunnan province, was one of the last places in the country to end the tradition. A decade ago, there were more than 300 women like Fu in the village. Now there are just 30, by her reckoning, and because they are all elderly, they rarely come down to the village center, where they once gathered to dance and hand-sew the doll-size shoes they wore. "Before the [Communist takeover in 1949], all of the girls in the village had to bind their feet. If they didn't do this, no man would marry them," says Fu, sitting on a wooden stool in her dusty home on the outskirts of the village, her feet unwrapped.

“In Liuyi, the foot binding didn't stop until around 1957. "I started the process in 1943 when I was 7," says Fu, who smiles at the memory of those youthful days. "At the beginning it hurt with every move I made, but I agreed to go on with the process because it is what every girl my age did. "My mother had bound feet, and her mother, and her mother," she says, trailing off, unsure just how many generations it went back.

“Yang Yang, who was born in Liuyi, says his late mother was one of the last women in the village to let out her feet, loosening the daily bindings so that they would become less restrictive. Yang, who lives in the nearby town of Tonghai, has written two books telling the stories of his mother and the women of the village. His mother died in 2005.

In Liuyi, even after the practice was banned, Fu says, she and others were hesitant to stop tightly binding their feet and hid them from officials, worried that the ban would be temporary. They also viewed their bound feet as desirable and something to be proud of. "We all thought our bound feet looked beautiful," she says, smiling. “In the 1980s, some of the remaining women started performing dances together, which eventually became an unusual tourist attraction until their decreasing numbers and mobility eventually brought the practice to an end. Fu remembers the dances fondly, though nowadays she spends most of her time looking after her great-grandchildren and caring for the house where four generations of her family live. "Whenever there was some big event we would all get altogether, dress up in beautiful clothing and dance. Other times we would just meet to sew our shoes," she says.

“Fu carefully wraps her feet and slides them back into her intricately sewn shoes. "I've lived a good life," she says. "I am proud to be part of the tradition, but I wouldn't want my daughter or granddaughters to have had to go through it.”

Image Sources: Images of bound feet from Brooklyn Collage, University of Washington, Ohio State University,

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021