WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE SOCIETY

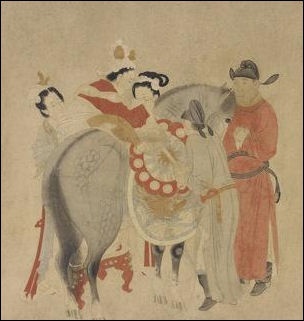

Yan Guifei, one of China's Four Beauties, mounting a horse

Traditional Chinese society was male-centered. Sons were preferred to daughters, and women were expected to be subordinate to fathers, husbands, and sons. A young woman had little voice in the decision on her marriage partner (neither did a young man). When married, it was she who left her natal family and community and went to live in a family and community of strangers where she was subordinate to her mother-in-law. Far fewer women were educated than men, and sketchy but consistent demographic evidence would seem to show that female infants and children had higher death rates and less chance of surviving to adulthood than males. In extreme cases, female infants were the victims of infanticide, and daughters were sold, as chattels, to brothels or to wealthy families. Bound feet, which were customary even for peasant women, symbolized the painful constraints of the female role. [Source: Library of Congress]

According to the Encyclopedia of Sexuality: “In its earliest history, China was a matriarchal society, until Confucius and Mencius defined the superior-inferior relationship between men and women as heaven-ordained more than two thousand years ago. In traditional Chinese society, women should observe the Three Obediences and the Four Virtues. Women were to be obedient to the father and elder brothers when young, to the husband when married, and to the sons when widowed. Thus the Chinese women were controlled and dominated by men from cradle to grave. [This may not apply to the lower class and marginal people. (Lau)] [Source: Zhonghua Renmin Gonghe Guo, Fang-fu Ruan, M.D., Ph.D., and M.P. Lau, M.D.Encyclopedia of Sexuality hu-berlin.de/sexology =]

The ideal of feminine behavior created a dependent being, at once inferior, passive, and obedient. Thus for more than 2,000 years, for the vast majority of Chinese women, belonging to a home was the only means to economic survival, but they had no right to select a husband, let alone the right to divorce or to remarry if widowed. They had no right to their physical bodies. Those who defied such institutionalized oppression were persecuted, ostracized, and sometimes driven to suicide. =

The functional importance of all women in traditional China lay in their reproductive role. In a patriarchal and authoritarian society, this reproductive function took the form of reproducing male descendents. Since descent was patrilineal, a woman’s position within her natal family was temporary and of no great importance. The predominant patrilineal household model, in combination with early marriage, meant that a young girl often left home before she was of significant labor value to her natal family. Hence, education or development of publicly useful skills for a girl was not encouraged in any way. Marriage was arranged by the parents with the family interests of continuity by bearing male children and running an efficient household in mind. Her position and security within her husband’s family remained ambiguous until she produced male heirs. [Then she might become manipulative and exploitive. (Lau)] In addition to the wife’s reproductive duties, the strict sexual division of labor demanded that she undertake total responsibility for child care, cooking, cleaning, and other domestic tasks. Women were like slaves or merchandize. =

See Separate Articles:CHINESE WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; TIGER MOTHER AMY CHUA factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WOMEN AND DRAGON LADIES IN CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; HARD LIFE OF WOMEN IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN UNDER COMMUNISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CONFUCIAN VIEWS AND TRADITIONS REGARDING WOMEN factsanddetails.com CONCUBINES AND MISTRESSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com PROBLEMS FACED BY WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com SUCCESSFUL WORKING WOMEN IN CHINA: DONG MINGZHU AND SHENGNU LADIES factsanddetails.com MEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN AND WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN TRAFFICKING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOOT BINDING AND SELF-COMBED WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE FAMILY factsanddetails.com ;

Good Websites and Sources: Women in China Sources fordham.edu/halsall ; Chinese Government Site on Women, All-China Women's Federation (ACWF) Women of China ; Human Trafficking Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery in China gvnet.com ; International Labor Organization ilo.org/public Foot Binding San Francisco Museum sfmuseum.org ; Angelfire angelfire.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Women in Ancient and Imperial China “Women in Ancient China” by Bret Hinsch Amazon.com; “Women in Early Medieval China” by Bret Hinsch a Amazon.com; “Wu Zhao: China's Only Female Emperor” by N. Rothschild Amazon.com; “Wu: The Chinese Empress who schemed, seduced and murdered her way to become a living God” by Jonathan Clements Amazon.com “Celestial Women: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Song to Qing” by Keith McMahon Amazon.com; “Women in Imperial China” by Bret Hinsch Amazon.com; “Courtesans, Concubines, and the Cult of Female Fidelity (Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series) by Beverly Bossler Amazon.com; Women in Pre-Revolutionary China “Instructions for Chinese Women and Girls” by Zhao Ban, Esther E Jerman, Amazon.com ; “The Chinese Book of Etiquette and Conduct for Women and Girls, Entitled, Instruction for Chinese Women and Girls” (1900) by Chao Pan Amazon.com; “The Mother (1931) by Pearl S. Buck Amazon.com; Women in Revolutionary China “Women and China's Revolutions” by Gail Hershatter Amazon.com; “To the Storm: the Odyssey of a Revolutionary Chinese Woman” by Yue Daiyun and Carolyn Wakeman Amazon.com; “A Daughter of Han: The Autobiography of a Chinese Working Woman” by Ida Pruitt (1945) Amazon.com

Three Feminine Obediences and Four Virtues of Confucianism

In a traditional male-dominated Confucian family, the eldest son is held in the highest esteem and is responsible for carrying on the family name and lineage, keeping property in the family and presiding over ancestral rites.The preference for boy babies over girls in Asian society is tied up in part in the Confucian belief that a male heir is necessary to carry on the family name, provide leadership for the family, and take care of the family ancestors. Chinese parents worry that if they don't produce a male heir no one will take care of them in their old age and no one will keep them company or look after them in the afterlife. Confucius famously said that a good woman is an illiterate one. Women often suffered under the Confucian system. Not only are they ordered around by men, they are often ordered around by each other in very vicious or mean ways. Older sisters have traditionally pushed their younger sisters around with impunity, and mothers of sons are notorious for treating their daughters-in-law like servants.

“The Three Obediences and Four Virtues” is the most basic set of moral principles and social behavioral guidelines for women in Confucianism. Even prostitutes were expected to follow them. Some imperial eunuchs and modern gay men both observed them themselves and enforced them. The terms "three obediences" and "four virtues" first appeared in the Book of Etiquette and Ceremonial (6th century B.C.) and in the Rites of Zhou (2nd century B.C.) respectively, which codified and defined different aspects of elegant and refined Chinese culture and harmonious society but were not intended as rule books. They had a great influence on China, Korea and Japan. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Three Feminine Obediences for females are to 1) obey, 2) bow to and 3) follow the spiritual, ethical and moral wisdom of: A) her father as a daughter; B) her husband as a chaste wife; and C) her sons. If a conflict arises she is expected to prioritize her father over her husband over her sons. As a widow and in the afterlife she is expected to be dedicated to her husband’s clan and family. The Four Feminine Virtues for women are: 1) Ethics in matrimony. 2) Speech in matrimony; 3) Virtue in Visage, in manners and appearance in matrimony; 4) "Kungfu" ("Works"), being chaste, monogamous, and a virgin when married.

See Separate Article CONFUCIANISM, FAMILY, SOCIETY, FILIAL PIETY AND RELATIONSHIPS factsanddetails.com

Early Confucianism and the Roles of Women in China

Joshua Wickerham wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender”: The teachings of Confucius (551-479 B.C.), are embodied in the Five Classics, which included the I Ching, and books of poetry, rites, history, and annals. These include some of the first references to the value of friendship, romantic scenes, and multifarious male and female roles. Confucius's philosophical, religious, moral, and social teachings were interpretation by later thinkers like Mencius (372-289 B.C.) and practically obliterated two centuries after his death during the short-lived Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.), which unified China, enshrined Legalism, and burned scholars and books alike. In the subsequent Han dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), what survived to be reinterpreted became the official state ideology, and has influenced East Asian life to this day. [Source: Joshua Wickerham, “Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Culture Society History”, Thomson Gale, 2007]

“Confucianists valued humans above animals because of their capacity for moral cultivation. Under the Confucian tradition, female education in literature, music, or the arts was for low-class performers, concubines, and prostitutes. Confucius believed that a woman's morals were worth cultivating, but her intellect was not. Should a woman gain an opportunity to cultivate her morals through art, letters, and music, she would rank just below a cultivated man.

“The Eastern Han (25 B.C.-220 A.D.) was the beginning of official government rhetoric against females. Officials denied women formal education because they were theorized as being dull and unteachable, despite Confucius's belief to the contrary. These early Confucianists taught that non-procreative sex was corrupting and that women's greatest gift was giving a husband a male heir. Of prime importance were roles, familial relations, the moral autonomy of all, and treating others as one would like to be treated. As can be seen in the section "I See on High," in the Odes, China's greatest Confucian moral tome, Confucius can be seen as at best favoring men and at worst being misogynistic when he said "Disorder does not descend from Heaven. It is born of women." Contrary to popular belief, Confucius was criticized in his own life for the respect he showed to women.

Neo-Confucianism and the Evolution of Women’s Roles in China

Joshua Wickerham wrote in the “Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender”: Comparatively very little is known about the structure of the Chinese family before the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when printing was invented and written sources became more widespread.

“Daughters were generally undesirable because of economic and patrilinial considerations. Only males could carry on the family name and daughters required dowries to attract male suitors — or a suitor's parents, as was usually the case. Unwanted daughters were often killed at birth or sold into slavery at age five or six. These trends strengthened with the rise of Neo-Confucian orthodoxy, starting as early as the Tang dynasty when scholar Han Yu (768-824) beginning calling for restraint in "unbridled passions."

“Gaining strength in the Southern (Later) Song dynasty (1127-1279), neo-Confucianists promulgated an extreme form of the ancient philosophy. From references in the classics that men and women should not freely associate, scholars and officials justified gender segregation in all spheres of life. This required them to overlook almost all references to romantic and sexual love in the poetry of the classics.

“Under succeeding dynasties, Neo-Confucianism generally gathered cultural currency. Talk of sex became taboo. Foot binding became widespread. Female infanticide became more common. Remarriage became rare as elites erected new monuments to the chaste female and the windowed martyr. Zhu Xi (1130-1200), one of the most influential Neo-Confucian scholars of his day, set the tone of the times in "Reflections on Things at Hand," when he wrote that "a man with passions has no strength, whereas a man of strength has no passions." The Neo-Confucianists departed from earlier schools with their rigid morality and a belief in the innate goodness of humans. Confucius believed goodness must be cultivated. In general, Neo-Confucianists naturalized gender distinctions, providing less opportunity for per-formative departure from gender roles.

“Zhu Xi's teacher, Sima Guang (1019-1086), taught that, at seven years old, boys and girls should no longer eat together. At eight, girls should not leave inner chambers, and should not engage in song and dance. He taught that remarriage was bad for both men and women alike. Girls should learn women's work, which meant cooking, cleaning, and "instruction in compliance and obedience."

“Though feminist historians attack Neo-Confucianists as deeply misogynistic, critics like Patricia Buckley Ebrey claim that the Neo-Confucianists' concern with remarriage reflected an extension of preexisting patriarchal concern for female welfare. Remarriage was seen as a threat to the financial stability of the family. These feminists also ascribe too much power to elite philosophers; one of Zhu Xi's disciples actually remarried.

“In this complex time, women held roles as slaves, empresses, mothers, wives, merchants, and beggars, but their general sphere was that of the household. According to Neo-Confucianists, chaste and productive women laid the foundation for a nation. Women had their own work, like weaving, which played as important or more important a role in the economy of late imperial China than did much "male" agricultural work.

Traditional Ideas About Women and Gender in China

Hsiang-ming kung wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”: “A daughter was trained for marriage, to be a good wife, nurturing mother, and a diligent daughter-in-law. The best training for marriage was illustrated in the Four Attributes — proper virtue, speech, carriage, and work. Should the daughter turn out to be a poor wife or an unfit daughter-in-law, criticism would be directed to her mother as the person responsible for her training in the domestic arts. [Source: Hsiang-ming kung, “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Dr. Eno wrote: “Within families – as within Chinese society as a whole – authority lay with the males, and among males, seniority was the principal index of authority. Because marriage within even the most extended of clans was forbidden, only males were full members of the family lineage – brides were married “out of” their natal families, meaning that young girls were destined before long to leave, and older women were outsiders to varying degrees, depending on how long since they had married into the family. For individuals, knowing that after death they would be dependent on their descendants for sustenance as spirits, nothing was more important than having children, and as daughters would marry out of the family and participate in feeding their husbands’ parents, rather than their own, each man and wife knew they would ultimately be dependent upon their sons. This contributed to the very high valuation of male children by both parents, and by society as a whole, while daughters were often regarded as an unwanted burden, useful only if an opportunity arose to marry them off to families higher up on the social and economic ladder. /+/

“The focus on the male-dominated family fostered authoritarian patterns. One of the cardinal human virtues in Chinese tradition was “filiality,” service and obedience to parents by children, especially male children. This stress on authority and obedience created a dynamic where young people who had been given few opportunities for initiative and independent thinking found themselves, upon the deaths of their fathers, called upon to exercise a relatively high degree of both. Among the educated classes where this was most true, the gap was filled by high emphasis on education outside the home, under the tutelage of male teachers other than one’s father.” The best way to approach our Classical Chinese thought with regard to gender issues is to recognize that the classical texts were written exclusively by males, and that the intended audience was also male. The assumption is that in discussing human ethics and human excellence, it is men of whom the text is speaking. But the texts also do not generally present any barriers that prevent us from reading their lessons as gender-free when we look to them for inspiration in our own, presumably less sexist age. /+/

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: “The present position of woman in China is a heritage of the remote past, as is illustrated by the most ancient Chinese literature, an example of which heads the present chapter. The instructions and the prohibitions in the Book of Rites, one of the oldest and most venerated classical works, embody fundamental principles which have always governed the Chinese in their treatment of women. The essence of the Chinese classical teaching on this subject is, that woman is as inferior to man as the earth is inferior to heaven; and that she can never attain to full equality with man. According to Chinese philosophy death and evil have their origin in the Yin, or female principle of Chinese dualism, while life and prosperity come from the subjection of it to the Yang, or male principle; hence it is regarded as a law of nature to keep woman completely under the power of man, and to allow her no will of her own. The result of this theory and the corresponding practice is that the ideal for women is not development and cultivation, but submission. Women can have no happiness of their own, but must live and work for men, the only practical escape from this degradation being found in becoming the mother of a son. Woman is bound by the same laws of existence in the other world. She belongs to the same husband, and is dependent for her happiness on the sacrifices offered by her descendants. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

Male Dominance in Traditional China

Bride groom's family in the 1930s

Dr. Eno wrote: “It is generally true that premodern societies worldwide gave dramatic priority to men over women. China was no exception, and in some respects male dominance was more profound than in other major world cultures...As we will see, the status and role of women, when explored in detail, was more complex than this brief characterization of subservience may suggest. However, when speaking of the main actors of cultural history in traditional China we will find ourselves with only a few exceptions speaking solely of men. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“Male dominance was not fully established at the start of Chinese civilization. When we explore the earliest evidence we have for Chinese culture, we see isolated instances of women playing significant public roles, and some scholars believe these were vestiges from the prehistoric past – there is a theory that at some distant time, perhaps before the advent of agriculture in about 7000 B.C., China was a “matriarchal” society, where women were dominant, though the evidence for this theory is very sparse. In time, Chinese traditions of male authority grew increasingly explicit, and whereas it is possible to read the early evidence as indicating that gender role differentiation reflected an idea of divided labor, rather than male superiority, by the early imperial era orthodox thought tended to celebrate men not only as stronger and more able public figures, but as better than women in a moral sense. /+/

“Sometime in the tenth century AD, the subordinate status of women was made physically explicit through the gradual spread of a unique custom, “footbinding,” in which the feet of young girls were intentionally reshaped through a long and painful process. The result of the process was to render women’s feet terribly small. This was perceived by Chinese as a reflection of grace and femininity, and was erotically attractive to men, but it rendered women physically unfit for any serious labor, and made it difficult for them even to exercise the independence of walking. /+/

Oppression of Women in Traditional China

While most developed traditional cultures in world history have been controlled by men at the expense of women, with of women confined to the home and men dominating community and state sectors, China was probably worse than most in its treatment of women, who were often viewed as little more than commodities. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Dr. Eno wrote: “It is probably correct to say that with only a few known exceptions, traditional cultures worldwide accorded much higher status and privilege to men than to women. China was not only no exception in this regard, its social values were probably more skewed towards male privilege than most societies. For example, in traditional China women were substantially separated from their birth families after marriage, girls were not provided with education, males possessed almost sole effective rights of property (widows were an exception), and men were permitted to take as many “secondary wives” (sometimes called “concubines”) as their wealth and status made socially acceptable.

“The extreme sexism of ancient China will seem deplorable to most modern Westerners, and certainly, it should be clearly acknowledged. However, ancient China cannot now be changed, and in this course we will not dwell overmuch on this aspect, except perhaps to note unanticipated aspects in which women may have been viewed or treated differently, or escaped somewhat the constraints placed on them. When discussing political activities, ethical ideals, and so forth, it will be pointless to employ the non-sexist language of “his or her,” “he or she.” Admirable ideal types, sages and rulers, will always be male, even in the abstract; it’s too bad, but to ascribe non-sexist ideas to the literate elite of ancient China would be a distortion. /+/

“Despite these cultural features of the traditional Chinese environment, it is interesting to note that philosophical texts almost never make a claim that women are in any way inferior to men. The most they will say (and many do say this) is that women and men are different in their natural capacities and should perform different functions in the world. The theme of this distinction is most essentially that the role of women is properly confined to the non-public sphere of family life. Chinese popular views of women in public life was traditionally that they were basically a dangerous force in that context. There were many stories of queens, empresses, and royal concubines who employed the power of their sexual allure to influence government — always for the worse. Most early thinkers seems to have accepted such accounts at face value and assumed that their students or readers would understand without saying the danger of women in public life — but it is also a fact that no ban on women’s aspirations was proclaimed or any statement made that they were, by nature, unfit or unable to achieve ideal forms of human excellence. And, in fact, one school of ancient thought, the Daoists, tended to celebrate female qualities as superior to male ones, and the key to human excellence. /+/

Impact of Marriage of Women

Newlyweds in the 1930s

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”:

“Generally, at marriage, the woman makes the greatest change. In some cases, as in China, she cuts off all previous family ties. The observations from anthropologists used by McLennan to develop his theory of marriage by capture may not be vestiges of an older tradition but a continuation of established practice. Similarly we cannot tell how much of the Aborigine capture episode described by the anonymous writer in Chambers Journal was actually prearranged and whether he or she, as an outsider, knew the whole story. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons” by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

“China There is a Chinese saying, “A daughter married is like water poured out the door,” that refers to the fact that when a girl marries, she leaves her family to become part of her husband’s family and, apart from a brief period immediately after the wedding, is completely cut off from her birth family. Traditionally, a Chinese woman whose parents were living, was referred to not only as a “girl, ” but as an unmarried girl (ku-niang), although she may have been the mother of six or seven children.

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: “A Chinese married woman has literally no name at all, but only two surnames, her husband’s and her father’s, so that when these chance to be common ones, it is impossible by this means to discriminate one woman from another. If Chinese women are to be addressed by strangers at all, there is even more embarrassment than in the case of men. In some regions the term Elder-sister-in-law (sao-tzŭ) serves indiscriminately for any woman, but in others Aunt (la-niang) must be used, while in yet others nothing is appropriate but Grandmother (nai-nai) which elsewhere would be equivalent to Old Granny. When there happen to be three generations of women in the same family to dub them all “Grandmother” (especially if one of them is a girl in her teens just married) is flagrantly absurd. Beggars at the other gates clamour to have their “Aunts” bestow a little food, and the phrase Old Lady (lao T‘ai-t‘ai) is in constant use for any woman past middle life.” [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

In 1950, the Communist Family Law provided freedom of divorce and equal status for women and defined the rights and duties of children. However, these laws and changes have only slowly had an effect on attitudes toward marriage and the role of women in Chinese society. Outside influences have also impinged upon Chinese society so that marriages have to be registered with a registrar and there may be a religious ceremony of marriage in a church (if the families are Christian) or in a temple. The One Child Policy initiated the late 1970s restricted couples to one child. This, along with the cultural imperative for Chinese men to have a son and heir, has encouraged neglect and abandonment of female babies and children, which, in turn, has led to a shortage of women for marriage. ^

Life of a Chinese Woman After Marriage

Hsiang-ming kung wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”: “Traditionally, Chinese girls married early — as soon as possible after puberty. Marriage brought about drastic changes in women's lives but not so in men's. Once a woman married, she had to leave her natal home and live with her husband's family. A frequent meeting with members from natal family was improper. The first duties for a woman were to her husband's parents, and secondly was she responsible to her husband. [Source: Hsiang-ming kung, “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”, Gale Group Inc., 2003 ==]

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: Every Chinese wife came by no choice of her own from some other family, being suddenly and irrevocably grafted as a wild stock upon the family tree of her husband. As we have already seen, she is not received with enthusiasm, much less with affection (the very idea of which in such a connection never enters any Chinese mind) but at best with mild toleration, and not infrequently with aggressive criticism. She forms a link with another set of interests from which by disruption she has indeed been dissevered, but where her attachments are centered. The affection of most Chinese children for their mothers is very real and lasting. The death of the mother is for a daughter especially the greatest of earthly calamities. Filial piety in its cruder and more practical aspects constantly leads the married daughter to wish to transfer some of the property of the husband’s family to that of her mother. The temptation to do so is often irresistible, and sometimes continues through life, albeit with many dramatic checks. The Chinese speak of this habit in metaphorical phrase as “a leak at the bottom” which is proverbially hard to stop. It is a current saying that of ten married daughters, nine pilfer more or less. It is not uncommon to hear this practice assigned as one of the means by which a family is reduced to the verge of poverty. The writer once had occasion to acquaint a Chinese friend with the fact that a connection by marriage had recently died. He replied thoughtfully: “It is well she is dead; she was gluttonous, she was lazy; and beside she stole things for her mother!” [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg; Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang,a village in Shandong.]

“Visits to the mother’s family constitute by far the most substantial joys in the life of a young Chinese married woman. It is her constant effort to make them as numerous as possible, and it is the desire of her husband’s family to restrict them, since her services are thus partially lost to them. To prevent them from being wholly so, she is frequently loaded down with twice as much sewing as she could do in the time allowed, and sent off with a troop of accompanying children, if she has reached so advanced a stage as to be a mother of a flock. An invasion of this kind is often regarded with open dissatisfaction by her father and brothers, and what could be more natural than her desire to appease them by the spoils which she may have wrested from the Philistines?

“After the death of her mother the situation has materially altered. The sisters-in-law have now no restraint on their criticisms upon her appearance with her hungry brood, and her whole stay may not improbably be a struggle to maintain what she regards as her rights. It is one of the many pathetic sights with which Chinese society abounds to witness the effort to seem to keep alive a spark of fire in coals which have visibly gone out. Not to have any “mother’s family” to which to go is regarded as the depth of misery for a married woman, since it is a proclamation that she no longer has any one to stand up for her in case she should be abused. To discontinue altogether the visits thither is to some extent a loss of face, which every Chinese feels keenly. We have known an old woman left absolutely alone in the world, obliged at the age of ninety-four to gather her own fuel and do whatever she wanted done for herself, except draw water, which was furnished her by a distant relative as an act of special grace. Her poverty was so abject that she was driven to mix fine earth with the little meal that sufficed for her scanty food, that it might last the longer. Yet this poor creature would sometimes be missed from her place, when it was reported that she had gone on a visit to her “mother’s family” consisting of the great-grandchildren of those whom she had known in youth!

“By the time a married woman had reached middle life her interest in her original home may have greatly weakened. There are now young marriageable girls of her own growing up, each of whom in turn repeats the experience of her mother. To their fathers and also to their brothers these girls are at once a problem and a menace. Could the birth-rate of girls be determined by ballot of all the males of full age, it is probable that in a few generations the Chinese race would become extinct. The expression “commodity-on-which-money-has-been-lost,” is a common periphrasis for a girl. They no sooner learn a little sewing, cooking, etc., than they are exported, and it is proverbial that water spilled on the ground is a synonym for a daughter. “Darnel will not do for the grain-tax, and daughters will never support their mothers.” These modes of speech represent modes of thought, and the prevailing thought, although happily not the only thought of the Chinese people.

Hsiang-ming kung wrote: “The Marriage Laws of 1950 and 1980 in China and the revisions of Civil Code in Taiwan have helped to raise the status of Chinese women. The average age at marriage has been rising for both men and women. Once married, women do not change their surnames. They also have full inheritance rights with men. Mandatory formal education and participating in paid labor market altogether increase wives' power to achieve a more egalitarian style of decision-making and domestic division of labor. This phenomenon is more predominant in cities than in rural areas, and is more common in China than in Taiwan. Despite the significant progress, the persistence of tradition still restricts women to inferior status. Wives' full-time paid employment does not guarantee that their husbands will help with household chores. Many young couples begin their marriages by living with the husband's instead of the wife's parents. The mother-inlaw/daughter-in-law relationship remains difficult. Visiting the natal home still frequently causes conflict between these two women. ==

Daughter-in-Law in a Chinese Family

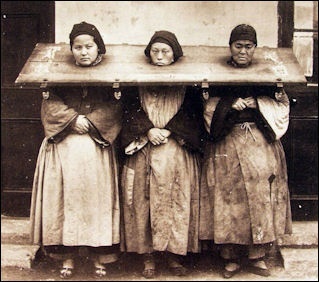

China in 1875

Chinese mothers of sons have traditionally been notorious for treating their daughters-in-laws like servants — worse. Tensions and conflict between mothers- and daughters- in-law has traditionally been frequent and palpable. The power, however, always lay with the mother-in-law due to age, seniority and place with China’s filial piety system. However hard she worked for her husband's family, a daughter-in-law was seldom counted as zi-jia-ren (true family member) and her primary duty was to produce a son. Without a son she an became outsider and was doomed to powerlessness. Her husband was allowed to take a concubine — presumably to produce a son — and the wife had to comply. [Source: Hsiang-ming kung, “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics” in 1894: “A daughter-in-law is regarded as a servant for the whole family, which is precisely her position, and in getting a servant, it is obviously desirable to get one who is strong and well grown, and who has "already been taught the domestic accomplishments of cooking, sewing, and whatever industries may be the means of livelihood in that particular region, rather than a child who has little strength or capacity. Thus we have known of a case where a buxom young woman of twenty was married to a slip of a boy literally only half her age, and in the early years of their wedded life she had the pleasure of nursing him through the small-pox, which is considered as a disease of infancy. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

“Mothers and daughters who pass their days in the narrow confinement of a Chinese court, under the conditions of Chinese life, are not likely to lack topics of disagreement, in which abusive language is indulged in with a freedom which the unconstraint of every day life tends to promote. It is a popular saying, full of significance to those who know Chinese homes, that a mother cannot by reviling her own daughter make her cease to be her own daughter! When a daughter is once married, she is regarded as having no more relations with her family, than those which are inseparable from community of origin. There is a deep-seated reason for omitting daughters from all family register. She is no longer our daughter, but the daughter-in-law of some one else. Human nature will assert itself, in requiring visits to the mother's home, at more or less frequent intervals, according to the local usage. In some districts these visits are very numerous and very prolonged, while in others the custom seems to be to make them as few as possible, and liable to almost complete suspension for long periods in case of a death in the family.

“But whatever the details of usage, the principle holds good, that the daughter-in-law belongs to the family of which she has become a part. When she goes to her mother's home, she goes on a strictly business basis. She takes with her it may be a quantity of sewing for her husband's family, which the wife's family must help her get through with. She is accompanied on each of these visits by as many of her children as possible, both to have her take care of them, and to have them out of the way when she is not at hand to look after them, and most especially to have them fed at the expense of the family of the maternal grandmother for as long a time as possible. In regions where visits of this sort are frequent, and where there are many daughters in a family, their constant raids on the old home are a source of perpetual terror to the whole family, and a serious tax on the common resources. For this reason these ^ftsits are often discouraged by the father and the brothers, while secretly favored by the mothers. But as local custom fixes for them certain epochs', such as a definite date after the NewYear, special feast days, etc., the visits cannot be interdicted.

Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: “To defend herself against the fearful odds which are often pitted against her, a Chinese wife has but two resources. One of them is her mother’s family, which, as we have seen, has no real power, and is too often to be compared to the stern light of a ship, of no service for protection in advance, and only throwing a lurid glare on the course which has been passed over, but which cannot be retraced. The other means of defence which a Chinese wife has at her command is — herself. If she is gifted with a fluent tongue, especially if it is backed by some of that hard common sense which so many Chinese exhibit, it must be a very peculiar household in which she does not hold her own. Real ability will assert itself, and such light as a Chinese woman possesses will assuredly permeate every corner of the domestic bushel under which it is of necessity hidden. If a Chinese wife has a violent temper, if she is able at a moment’s notice to raise a tornado about next to nothing, and to keep it for an indefinite period blowing at the rate of a hundred miles an hour, the position of such a woman is almost certainly secure. The most termagant of mothers-in-law hesitates to attack a daughter-in-law who has no fear of men or of demons, and who is fully equal to any emergency. A Chinese woman in a fury is a spectacle by no means uncommon. But during the time of the most violent paroxysms of fury, Vesuvius itself is not more unmanageable by man.” [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

Old Age and Widowhood

Hsiang-ming kung wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”: “The elderly, as the closest living contacts with ancestors, traditionally received humble respect and esteem from younger family members and had first claim on the family's resources. This was the most secure and comfortable period for men and women alike. Filial piety ensured that the old father still preserved the privilege of venting his anger upon any member of the family, even though his authority in the fields might lessen as he aged. His wife, having produced a male heir, was partner to her husband rather than an outsider in maintaining the family. If not pleased, she had the authority to ask her son to divorce his wife. However, due to her gender, her power was never as complete as her husband's. [Source: Hsiang-ming kung, “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

“The life of widows in traditional China was no less miserable than that of divorced women. Although widowers could remarry without restraint, the pressure of public opinion ever since Sung dynasty (A.D. 960-1279) prevented widows from remarrying. The remarriage of widows was discouraged, and their husbands' families could actually block a remarriage. Nor could the widow take property with her into a remarriage. The only way a widow could retain a position of honor was to stay as the elderly mother in her late husband's home. This way, her family could procure an honorific arch after her death (Yao 1983). A widow's well-being was less valuable than the family's fame.

“The decline in fertility and increase in life expectancy both contribute to the growth in the aging population for Taiwan and China. Modern industrial life has weakened the superior status of the aged. The power of filial norms that call for children to live with their elderly parents has declined (Yeh 1997, Xiao 1999). Many aged persons are in danger of being left without financial support. The situation is even worse for aged women because they experience double jeopardy on age and gender grounds. Those elderly parents who still live with their adult son usually have to help with house keeping, child caring, and they sometimes suffer from the grimaces of the younger generation. Elderly abuse is no longer a rare phenomenon. Regardless of revisions of the inheritance laws that guarantee the inheritance rights of widows as well as the elimination of the value of widowhood chastity, remarriage for widows, especially those with grown children, continues to be considered disgraceful. In fact, widowed as well as divorced women in Taiwan experience the highest distress level compared with men and women across all marital statuses.

Chinese Scientists Make Subservient and Insecure a “Robot Goddess”

In 2016, researchers from the University of Science and Technology in China (USTC) unveiled and an ultra-realistic female robot named Jia Jia that was capable of basic communication and interaction with people, had natural facial expressions and behavior viewed by some unwelcomely stereotypical. Dyllan Furness wrote in Digital Trends: “For example, if Jia Jia detects that someone is taking a photo of her, she’ll warn the photographer to stand back or else the picture will make her face “look fat.” Jia Jia can’t do much beyond that though. Essential human emotional responses like laughing and crying are not in the robot’s repertoire. Her hands have also been left lifeless. She does, however, speak super subserviently. The prompt, “Hello,” elicits the reply, “Yes my lord. What can I do for you?” [Source: Dyllan Furness, Digital Trends, April 18, 2016]

“We’ve seen a few other ultra-realistic female robots recently. A few weeks ago a 42-year-old product and graphic designer from Hong Kong revealed “Mark 1,” a $50,000 female robot he built himself to resemble Scarlett Johansson. The project, which took a year and a half to complete, was supposedly the fulfillment of a childhood dream. Like Jia Jia, Mark 1 is capable of basic human-like interaction, command responses, and movement. Mark 1 actually outperforms Jia Jia in that the former can move its limbs, turn its head, bow, smirk, and wink.

“And that’s just the most recent example. Last year researchers at the Intelligent Robotics Laboratory at Osaka University in Japan and Shanghai Shenqing Industry in China revealed Yangyang, a dynamic robot with an uncanny resemblance to Sarah Palin. Yangyang also seems to do more than Jia Jia with its abilities to hug and shake hands. The USTC researchers spent three years developing Jia Jia, an apparent labor of love. And they aren’t done yet. Team director Chen Xiaoping says he hopes to develop and refine their creation, equipping it with artificial intelligence through deep learning and the ability to recognize people’s facial expressions, according to Xinhua News. Chen hopes Jia Jia will become an intelligence “robot goddess.” He added that the prototype was “priceless” and would not yet consider mass production.

Image Sources: 1) Historical photos, Lotte Moon and University of Washington; 2) Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 3) Village woman, Beifan 4) Urban woman, cgstock.com http://www.cgstock.com/china ; Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021