CHILDREN IN CHINA

In Asia, children are sometimes seen less as individuals who are supposed to find themselves and more as people within a family unit that have responsibilities to the family unit and are required to help keep the family going. These ideas are at least partly rooted in ancestor worship and Confucianism. Children are regarded as extensions of their parents, arguably more than in other places. Children of criminals are often treated like they are criminals themselves. If a man is regarded as a hero, his children are often regarded as heroes too.

In Asia, children are sometimes seen less as individuals who are supposed to find themselves and more as people within a family unit that have responsibilities to the family unit and are required to help keep the family going. These ideas are at least partly rooted in ancestor worship and Confucianism. Children are regarded as extensions of their parents, arguably more than in other places. Children of criminals are often treated like they are criminals themselves. If a man is regarded as a hero, his children are often regarded as heroes too.

Children are generally encouraged to spend their time studying not playing outside or participating in sports. Parents put a lot of pressure on their kids to study. The Economist reported: “Many older Chinese believe this younger generation, doted on by grandparents and parents, lacks a work ethic. It has even become a bit of a slur to say of someone that “they were born in the 1980s”. [Source: The Economist , August 18, 2007]

Chinese lavish great care and affection upon children Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: “At local restaurants, wait staff will whisk your child away to look at fish or take a few spins around the room to explore. Old people will sit on a park bench and hold long, delighted conversations with a toddler. Blonde haired, blue eyed babies are a special attraction. Chinese have no qualms about walking up and planting a kiss on a chubby hand, or even pick up or hold your child. Some children in their twos and threes begin to feel threatened by the amount of attention they receive on the street in China. If you prefer strangers to not touch your child, you will need to devise a polite way of discouraging it. The Chinese do not intend any harm with the attention. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

In the old days it wasn’t uncommon for villagers to sell their children, "Before Liberation" in 1949, a peasant farmer told the New York Times, "I was just a farm hand, working for the landlord, because I didn't have any land. I had two sons then, but I had to sell them because I didn't have any money. I was ill with typhoid. So I sold my two boys for 400 pounds of rice each. I never saw them again." In some parts of China, people paid a few pennies at traditional fairs to gawk at basket-shaped children who were brought up in baskets. Up until the 1950s, one of five children died before the age of one.

A survey carried out by the Japan Youth research Institute involving 7,200 high school students from Japan, China, the United States and South Korea found that Chinese students had relatively high levels of self confidence and satisfaction with themselves. According to the survey only 36 percent of Japanese students said they were valuable people compared to 89.1 percent among the Americans, 87.7 percent among Chinese and 75.1 percent among South Koreans. Asked if they are satisfied with themselves 78.2 percent of the Americans, 68.5 percent of the Chinese and 63.3 percent of the South Koreans said yes but only 24.7 percent of the Japanese said yes.

See Separate Articles: CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; BABIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SURROGATE BIRTHS, FROZEN EGGS AND IN-VITRO TREATMENTS AMONG CHINESE factsanddetails.com ; LITTLE EMPERORS AND MIDDLE CLASS KIDS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILDREN IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ONE-CHILD POLICY factsanddetails.com ; SERIOUS PROBLEMS WITH THE ONE-CHILD POLICY: factsanddetails.com ; END OF THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE EDUCATION Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE SCHOOLS Factsanddetails.com/China ; SCHOOL LIFE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; UNWANTED CHILDREN AND ADOPTIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINA’S LEFT-BEHIND CHILDREN factsanddetails.com ; CHILD ABDUCTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SALE OF BABIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PARENTS SEEKING KIDNAPPED CHILDREN factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Busy Kids chinadaily.com. ; Precious Children PBS piece pbs.org Young People ; Sheyla’s News blog /sheylawu.blogspot.com ; Human Trafficking Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery in China gvnet.com International Labor Organization ilo.org/public

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Children Of China” by Ann-Ping Chi Amazon.com; “Child Rearing in Rural China” by Jiang Youchun and Yang Yuny Amazon.com; “Children’s Literature and Transnational Knowledge in Modern China: Education, Religion, and Childhood” by Shih-Wen Sue Chen Amazon.com; “Love's Uncertainty: The Politics and Ethics of Child Rearing in Contemporary China” by Teresa Kuan Amazon.com; “Understanding the Chinese Personality: Parenting, Schooling, Values, Morality, Relations, and Personality” (1998) by William J. F. Lew Amazon.com; “The Children of China's Great Migration” by Rachel Murphy Amazon.com; “Handbook on the Family and Marriage in China (Handbooks of Research on Contemporary China series) by Xiaowei Zang, Lucy X. Zhao Amazon.com; “Family Life in China (2016) by William R. Jankowiak and Robert L. Moore Amazon.com; “China's Hidden Children: Abandonment, Adoption, and the Human Costs of the One-Child Policy” by Kay Ann Johnson (2017) Amazon.com

Children Statistics for China

Education: Adjusted net attendance rate, primary education: 95 percent.

Adjusted net attendance rate, lower secondary education: 73 percent.

Adjusted net attendance rate, upper secondary education: 60 percent

Completion rate, primary education: 97 percent

Youth literacy rate (15-24 years): 100 percent

[Source: UNICEF DATA data.unicef.org]

Health: Under-five mortality rate (U5MR): 7.9 per 1,000 live births.

Percentage of infants who received three doses of DTP vaccine: 99 percent

Percentage of children who received the second dose of measles containing vaccine: 99 percent

In the mid-1990s, China vaccinated a high percentage of its children up to one year of age: tuberculosis, 94 percent; diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus, 93 percent; polio, 94 percent; and measles, 89 percent. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Number of under-five deaths: 132,256

Infant mortality rate (IMR): 7 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Neonatal mortality rate (NMR): 4 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Male under-five mortality rate (U5MR): 8 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Female under-five mortality rate (U5MR): 7 deaths per 1,000 live birth.

Maternal and Newborn Health: Proportion of women aged 15-49 who received postnatal care within 2 days after giving birth: 64 percent.

Antenatal care coverage for at least four visits: 81 percent.

Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel: 100 percent.

Caesarean section: 41 percent.

Proportion of women 20-24 years old who gave birth before age 18: percent.

Maternal mortality ratio (number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births): 29 percent.

Births who had their first postnatal checkup within the first two days after birth: 63 percent.

Nutrition: Early initiation of breastfeeding (within one hour of birth): 29 percent.

Exclusive breastfeeding: percent. (<6 months): 21 percent.

Continued breastfeeding rate (20-23 months) at one year: 7 percent

Prevalence of moderate and severe stunting: percent.: 5 percent

Proportion of households consuming iodized salt: 96 percent.

The number of newborns with birth defects was rising in the 2000s. The rate of physical abnormalities among newborns in Beijing was 170 per 10,000 births in 2009, nearly double the rate in 1997. The problems is blamed on women having children later and environmental pollution. Smaller scale injury surveys in China indicate that injury is a leading killer of children over 1 year of age in Asia. “There is an injury epidemic across all over Asia and it's not just young children under 5 years of age. Half of all the injury deaths occur in children between the ages of 6 and 17," said President of The Alliance for Safe Children Ambassador Pete Petersen. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Zhu Ziqing on His Five Children

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: ““Zhu Ziqing (1898-1948) achieved fame as a writer of poetry, criticisms, sketches, and essays in the decades immediately following the May Fourth Movement. As a 1920 graduate of Beijing University, Zhu was certainly influenced by the cultural debates of the May Fourth period. The essay below concerns his views on his family, and particularly his five children. [Source:Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

In “My Children”, Zhu Ziqing wrote: “Amao is now, five months old. When you touch her chin or make faces, she will open her toothless mouth and, give out a gurgling laugh. Her smile is like a flower unfolding. She does not like to be inside for long and if she is, she cries out loudly. Mother often says, “The little girl wants to take a walk;, like a bird, she has to flit away once in a while.”, Runer was three just last month; a clumsy one, he cannot yet speak well. He can only say, three or four-word sentences with no regard for grammar and a blurred pronunciation, getting, every word out only with great effort. It always makes us laugh. When he wants to say hao, [good], it comes out like xiao [small]. If you ask him, “Are you well?” he will reply “small” or, “not small.” We often make him say these words for the fun of it, and it seems he now suspects, as much and has recently begun to say a correct hao, especially when we purposely want him to, say xiao. He has an enamel cup which we bought for about ten cents. The maid had told him, “This is ten cents.” All he remembered were two words “ten cents” and he therefore used to call, his cup “ten cents,” sometimes abbreviated to “cents.” When that maid left, the term had to be, translated for the new one. If he is embarrassed or sees a stranger, he has a way of staring, openmouthed with a silly smile; we call him a silly boy in our native dialect. He is a little fatty, with short legs, funny to look at when he waddles along, and if he hurries, he is quite a sight. [Source: “My Children” by Zhu Ziqing, Translated by Ernst Wolff from “Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook”, edited by Patricia Buckley Ebrey, 2nd ed. (New York: The Free Press, 1993), 391-395; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Sometimes he imitates me, clasping his hands behind him and walking with a swinging gait. He, will then laugh at himself and also make us laugh. His big sister Acai is over seven years old and goes to elementary school. At the table she prattles along breathlessly with stories of her schoolmates or their parents, whether anybody wants to listen or not. She always ends with a “Dad, do you know them?” or “Dad did you know that?” Since Mother does not allow her to talk while eating, she always addresses herself to me. She is always full of questions. After the movies, she asks whether the people on the screen are real, and if so, why they don’t talk. The same with photographs. Somebody must have told her that soldiers beat up people, which prompted her to ask, “Are soldiers human beings? Why do they beat people?” Recently, probably because her teacher made certain remarks, she came home and asked, “Whose side is Zhang Zuolin on?4 Are Jiang Jieshi’s soldiers helping us?” Endless questions of this type are used to pester me every day, and often they back me into a corner for want of an answer. When she plays with Runer, they make an incongruous pair, one big and one small, and there is constant quarreling and crying. But sometimes they seem to get along. For instance, one might hide under the bed and the other try to squeeze in pursuit. Then out they come, one after the other, from this bed to that. All one hears is their laughter, shouting and panting, as Mother would say, just like little dogs. Now in Beijing there are only these three children with us since, when we came north last year Grandmother took Ajiu and Zhuaner back to stay at Yangzhou for the time being. [4 Zhang Zuolin (1873-1928) was the warlord in Manchuria]

“Ajiu loves books; he likes to read Water Margin, The Journey to the West, Heroes of the Sword, Little Friend, and so on. He reads whenever he has a spare moment, sitting or lying, down. The only book he dislikes is The Dream of the Red Chamber, which, he says, has no flavor;, and indeed a ten.year.old can hardly be expected to appreciate its flavor.

“Last year we had to leave behind two of the children. Since Ajiu was a bigger boy and, since Zhuanger had always been with Grandmother, we left them behind in Shanghai. I, remember very clearly the morning of our parting. I brought Ajiu from the hotel at Two Stream Bridge to where Mother and Zhuanger were staying with some friends. Mother had told me to, buy something to eat for them, so at Sima Street I went into a restaurant. Ajiu wanted some, smoked fish, which I bought for him along with some cookies for Zhuanger. Then we went by, streetcar to Haining Street. When we got off, I noticed an expression of apprehension and, discomfort on his face. I had to hurry back to the hotel to prepare things for the journey and, could say only one or two words to the children. Zhuanger looked at me silently while Ajiu, turned to say something to Grandmother. I looked back once, then left, feeling myself the target, of their recriminatory glances. Mother later told me that Ajiu had said behind my back, “I know, Father prefers little sister and won’t take me to Beijing,” but this was really not doing me justice.

“He also pleaded, “At summer vacation time, you must come and pick me up,” which we, promised to do. Now it is already the second summer and the children are still left waiting in faraway, Yangzhou. Do they hate us or miss us? Mother has never stopped longing for her two children. Often she has wept secretly, but what could I do? Just thinking of the old anonymous poem, “It’s the lot of the poor to live with constant reunions and separations,” saddened me no end.

“Zhuanger has become even more of a stranger to me, but last year when leaving White Horse, Lake, she spoke up in her crude Hangzhou dialect (at that time she had never been in, Yangzhou) and her especially sharp voice: “I want to go to Beijing.” What did she know of, Beijing? She was just repeating what she had heard from the big children. But still, remembering how she said it makes me terribly sad. It was not unusual for these two children, to be separated from me, and they had also been separated from Mother once, but this time it, has been too long. How can their little hearts endure such loneliness? Most of my friends love children. Shaogu once wrote to reproach me for some of my, attitudes. He said that children’s noises are something to be cherished. How could anyone hate, them as I had said? He said he really could not understand me.

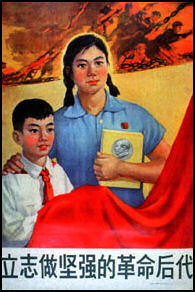

Childhood Under Mao

For most rural parents the choice a career for their children has never been a major issue. Under Communism, most children of peasants remained peasants like their parents, and the highest realistic ambition was a position as a lowlevel cadre or teacher or perhaps a technician. Many of the dynamics of urban society revolved around the issue of job allocation and the attempts of parents in the better-off segments of society to transmit their favored position to their children. The allocation of scarce and desirable goods, in this case jobs, was a political issue and one that has been endemic since the late 1950s. These questions lay behind the changes in educational policy, the attempts in the 1960s and 1970s to settle urban youth in the countryside, the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, and the post-1980 encouragement of small-scale private and collective commerce and service occupations in the cities. All have been attempts to solve the problem, and each attempt has its own costs and drawbacks. [Source: Library of Congress]

For most rural parents the choice a career for their children has never been a major issue. Under Communism, most children of peasants remained peasants like their parents, and the highest realistic ambition was a position as a lowlevel cadre or teacher or perhaps a technician. Many of the dynamics of urban society revolved around the issue of job allocation and the attempts of parents in the better-off segments of society to transmit their favored position to their children. The allocation of scarce and desirable goods, in this case jobs, was a political issue and one that has been endemic since the late 1950s. These questions lay behind the changes in educational policy, the attempts in the 1960s and 1970s to settle urban youth in the countryside, the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, and the post-1980 encouragement of small-scale private and collective commerce and service occupations in the cities. All have been attempts to solve the problem, and each attempt has its own costs and drawbacks. [Source: Library of Congress]

Ni Ching Ching wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Class struggle permeated every aspect of our supposedly egalitarian n society. Even as a child I was branded a capitalist because of my grandparents educations... I envied my classmate who lived a floor below me. She was the daughter of factory workers...She was always better than I because she worked harder and never complained or tried to quit. I thought she was a trur patriot. Instead she told me later she stayed so she could make it the next level and win a new jumpsuit...That was a great motivator. Children got new clothes only once a year.”

Ni wrote: “I was in the first grade when the teacher asked us one day to tell the class the names of people they knew who visited Tiananmen Square during a counterrevolutionary gathering. It was a spontaneous people’s movement to commemorate the death of Premier Chou En-lai...I was only 8 and I had no idea that my teachers were trying to trick me. So I raised my hand and volunteered my mother’s name...When I told my parents, they panicked. My mother went into hiding and I had to live with the guilt of betraying her.”

Stevan Harrell wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Under Communism childhood has been altered in important ways by the spread of education (almost universal for a few years, at least) and by the decline in fertility. Children cannot be significant sources of labor, but they can provide hope of social mobility through educational advancement, outside of remote areas of the rural mainland. They must therefore be pushed to do well in school, but also must be afforded time to study. The decline in fertility means more attention to the individual child and also higher expectations. Mainland Chinese psychologists have recently started studies of the "little emperors and empresses" that many people think today's only children have become. [Source: Stevan Harrell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia — Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Rural Children in China

Village children take on responsibility at an early age, often tending animals such as buffalo, cows, goats and sheep. Boys have traditionally taken care of animals and worked in the fields. Girls have traditionally collected water and grinded and threshed grain. Older siblings (especially girls) often help take care of the younger children. In poor families, children are often forced to work and earn money rather than attend school.

When they are five or six rural kids begin helping their sibling tend goats and other animals. When they are seven or eight they have enough skill to take care of 20 or so goats by themselves.

Many parents leave their villages to search for work, leaving their children behind to be brought up by grandparents or other relatives. The only time the children see their parents is when they return home over Chinese New Year holiday and even then often they don’t make it home because they are required to work at their factory or construction site.

These so called “left-behind” children number in the tens of millions and even hundreds of million because there are that many migrant workers in the cities. One 14-year-old who lived alone for a year after her father left for a construction job told the Los Angeles Times, “My parents are away making money so I can have a better life. But I don’t care about living a better life. I just want them to be home at my side.”

One school principal told the Los Angeles Times, “Most of these students tend to become antisocial and introverted. But in times of conflict, they tend to explode and react in violent extremes.” A school counselor said, “These children are so sad. They have to learn early to fend for themselves. There’s one family where the grandparents are taking care of four children from three of their sons. All of them are away at work. At best they can make sure the kids are clothed and fed. But they can’t fill the emotional emptiness.”

See Separate Article CHINA’S LEFT-BEHIND CHILDREN factsanddetails.com

Laws Regarding Children in China

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) declares that it protects a wide range of children’s rights through domestic legislation and by ratifying and joining the relevant international treaties. The PRC Constitution provides for the state protection of children, and prohibits maltreatment of children. Among many laws and regulations providing children’s rights protection, the primary law in this field is ThePRC Law on the Protection of Minors (first passed in 1991, revised in 2006) (Minors Protection Law). The revised Minors Protection Law entered into force on June 1, 2007. This law sets up responsibilities of the families, the schools, and the government with regard to the protection of children’s rights, and judicial protection, as well. [Source: Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, 2007 |*|]

Eighteen is the age of majority under Chinese civil law. According to the The General Rules of Civil Law (GRCL) — which set forth provisions concerning the basic rules of China’s civil law and was passed on March 15, 2017, and took effect on October 1, 2017 — a natural person aged eighteen or over is an adult; a natural person under the age of eighteen is a minor. An adult has full capacity for civil conduct under Chinese law. A minor whose main source of income is his or her job is deemed to be a person of full capacity for civil conduct. Minors aged eight to eighteen have limited capacity for civil conduct and may only independently perform limited civil acts. Minors under eight years old have no civil capacity and must be represented by guardians when performing any civil acts. [Source: Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, 2019]

China has ratified many major international documents with regard to children's rights protection. China's domestic legislation also provides protection for a wide range of children's rights. The reality, however, is disputable. Few accurate statistics could be obtained directly from the official source. In practice, enforcement of the treaty obligations and the legislative declarations remains a huge problem. |Major international documents relating to children’s rights that the PRC government has signed and ratified are as follows: U.N. Convention on Rights of the Child 1989 (CRC) (Entry into force for China: April 1, 1992); Optional Protocol to the Convention on Rights of Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution, and Child Pornography 2000 (Entry into force for China: January 3, 2003); International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1966 (Entry into force for China: June 27, 2001); The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women 1979 (Entry into force for China: December 3, 1981); Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention 1999 (Entry into force for China: August 8, 2003); The Hague Convention on the Protection of Children and Cooperation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption 1993 (Receipt of Instrument: September 16, 2005). |*|

Child Protection Laws in China

The Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (PRC or China) prohibits the maltreatment of children and declares that children are protected by the state. According to article 49 of the Constitution, “[m]arriage, family, mothers, and children are protected by the state.” The same article states that “[p]arents have the duty to rear and educate their children who are minors, and children who have come of age have the duty to support and assist their parents. ... Maltreatment of old people, women, and children is prohibited.” [Source: Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, 2019 ^/^]

As early as 1991, China passed the Law on the Protection of Minors aiming to protect the physical and mental health of minors and safeguard their lawful rights and interests. Although the Law forbids the maltreatment or abandonment of minors in general, it lacks detailed provisions concerning the mechanisms for responding to child abuse and neglect. China’s child protection laws appear to have rapidly developed over the past several years in response to media exposure of prominent incidents of child abuse and neglect, which brought the urgency of child protection issues to the public’s attention. The most significant development in this area includes the Ninth Amendment to the Criminal Law of 2015, which revised several articles of the Criminal Law concerning crimes against children. Also in 2015, China introduced its first Anti-Domestic Violence Law, which vows to provide special protection to children against family violence. Abusing a family member may constitute a crime punishable by up to seven years’ imprisonment. A 2015 amendment to the Criminal Law extends the scope of application of the crime of abuse to caregivers and legal guardians in institutions and other facilities. ^/^

Under the civil law, parents are guardians of their minor children. The 2017 General Rules of Civil Law specify the circumstances in which guardianship may be terminated, including where a guardian seriously damages the physical or mental health of the ward, or where the guardian’s negligence in performing his/her duties causes difficulties for and danger to the ward. The 2015 Anti-Domestic Violence Law requires educators, health providers, social workers, and community committee members to report domestic violence against children. The Law also addresses the temporary resettlement of children who have suffered domestic violence and the termination of guardianships of domestic violence perpetrators.^/^

The PRC Law on the Protection of Minors was first passed in 1991 and revised in 2006. The Law sets forth responsibilities of families, schools, and the state with regard to the protection of minors, and addresses judicial procedures applicable to cases involving minors. The Law on Protection of Minors forbids domestic violence against minors, maltreatment or abandonment of minors, or infanticide: Article 10 The parents or other guardians of minors shall create a good and harmonious home environment and, according to law, fulfill their responsibility of guardianship and their obligations to bring up the minors. Domestic violence against minors is prohibited. Maltreating or forsaking of minors is prohibited. Infanticide by drowning, brutally injuring or killing of infants is prohibited. No female or handicapped minors may be discriminated against. ^/^

The Law requires parents or other guardians of minors to “pay close attention to the minors’ physiological and psychological conditions and their behavioral habits.” Parents and other guardians must guide minors to participate in activities that are conducive to their physical and mental health and prevent them from smoking, drinking, using drugs, gambling, etc. Where parents work in other places and thus cannot perform their duty of guardianship with respect to their children, the parents must entrust other adults who have the ability to act as guardians with such duty. ^/^

Child Health and Social Welfare Laws in China

The primary law governing child health in China is The PRC Law on Maternal and Infant Health (promulgated by the NPC Standing Committee, effective June 1, 1995) (Maternal and Infant Health Law). According to Article 2 of the Maternal and Infant Health Law, “[t]he State shall develop maternal and infant health care projects and provide the necessary environments and material aids so as to ensure that mothers and infants receive medical and health care services.” [Source: Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, 2007 |*|]

The 135-article law covers pre-marital healthcare, pre-natal and post-natal healthcare, administrative provisions for medical assistance and facilities for treatment and health. The law requires medical institutions to offer pre-marital healthcare service, including health instruction, consultation, and medical examination. In cases of certain serious genetic disease found through the examination, long-term contraceptive measures or performance of tubal ligation operations shall be taken upon the agreement of the marrying couple. Medical institutions are also required to provide pre-natal and post-natal healthcare, including instructions, healthcare services for pregnant women, women ready for delivery at the hospital, fetuses, and newborns. |*|

As the body authorized to implement the law, the PRC State Council (China’s cabinet) issued an Implementation Rules of the Maternal and Infant Health Law in 2001 It is worth noting that although the law sets up the duties for medical institutions and local governments in offering and assisting maternal and infant healthcare, the services are not always free. The only service clearly provided by this law to be free is in Article 19: “The operations of terminating gestation or ligation operations in accordance with the law are free of any charge.”

Academic Studies on Children in China

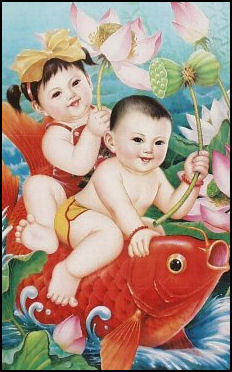

Jon L. Saari wrote in “Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood in History and Society”: In 1991, for a handbook on the history of childhood and children, historian John Dardess made a brief and masterful excursion into the history of childhood in premodern China, a subject he said had been "wholly untouched until recently". Some of that richness of source material has been mined in books, particularly in “Chinese Views of Childhood” (1995) and “Children in Chinese Art” by edited by Ann Barrott Wicks (2002). “Chinese Views of Childhood”, edited by Anne Behnke Kinney, brings together eleven scholars and the lenses of six academic disciplines. Among other things it explores art from the Song dynasty to the Qing dynasty revealed a persistent concern for the production of multiple sons, conveying the "accepted propaganda for a hundred generations", Surviving texts on elite family rituals and family instructions, explored by Patricia Ebrey, have yielded rich insights into the institutional context of children's lives. [Source:Jon L. Saari, Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood in History and Society, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

Joseph M. Hawes and N. Ray Hiner, editors of the 1991 handbook “Children in Historical and Comparative Perspective” explore things like Chinese traditions concerning childhood was the early introduction of state-sponsored Confucian education for a small elite, with occasional openings for a talented peasant child. In his 1982 and 1990 studies, Jon L. Saari postulates that the supposedly monolithic family system had enough vulnerabilities and the cultural tradition sufficient variation to permit mischievous children to survive the intense pressures for filial behavior. New supports outside the family in coastal cities and in new-style schools after 1905 allowed some to become cultural innovators and political reformers.

“The most controversial insights along these lines have come from the subfield of "political culture." Political scientist Richard H. Solomon argued that the twentieth-century Communist revolution has been in large part an unsuccessful Maoist effort to break out of the pattern of authoritarian leaders and deferential followers. A substantial part of his 1971 study, based on interviews and surveys, was a portrayal of traditional socialization within the family. A sharp break between the two halves of childhood — indulgent care up to age six and strict and uncompromising discipline and training thereafter — created ambivalence about authority and undermined the sense of individual autonomy. This view of the negative effects of traditional socialization, also promoted by a group of psychologists in Taiwan, led to counterarguments, particularly by Thomas A. Metzger in a 1977 study.

A 1990 work by Jon L. Saari, Legacies of Childhood: Growing Up Chinese in a Time of Crisis, 1890-1920, seized these advantages by interviewing adult Chinese about their childhoods and youth. Cultural critics and reformers like Lu Xun (1881-1936) raised the cry of "Save the children" (from the last line of his famous short story "The Diary of a Madman"), for they felt that only young people could forge new pathways for a society and polity mired in conservatism and reaction.

Image Sources: 1) Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ ; 2) Baby, Growing up, Beifan.com ; 3) 100 children painting, University of Washington; 4) Rural children, Bucklin archives 5) Adoption, Scafiido Family website ; 6) Baby for sale, Agnes Smedly

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021