TRADITIONAL VIEWS ON CHILDREN AND CHILD REARING CUSTOMS IN CHINA

Song-dynasty painting 100 Children Although Chinese families continue to be marked by respect for parents and a substantial degree of filial subordination, parents have weighty obligations toward their children as well. Children are obliged to support parents in their old age, and parents are obliged to give their children as favorable a place in the world as they can. In the past this meant leaving them property and providing the best education or training possible. The primary determinant of a rural child's status and well-being remains his or her family, which is one reason for the intense concern with the marriage choices of sons and daughters and for the greater degree of parental involvement in those decisions. Urban parents are less concerned with whom their children marry but are more concerned with their education and eventual careers. Urban parents can expect to leave their children very little in the way of property, but they do their best to prepare them for secure and desirable jobs in the state sector. The difficulty is that such jobs are limited, competition is intense, and the criteria for entry have changed radically several times since the early 1950s. [Source: Library of Congress ]

Hsiang-ming kung wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”: “The Chinese were tender and affectionate toward small children. Discipline was held to a minimum. Through story-telling, for example, young children learned to obey their parents and older siblings, and, more importantly, to devote themselves to be filial. At the age of three or four, some restrictions began, as did segregation by gender. Boys were under their fathers' direct supervision. Girls were inducted into women's tasks. Education for girls was considered unnecessary and even harmful. [Source: Hsiang-ming kung, “International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family”, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Little is known of socialization in earlier periods of Chinese history, but in traditional rural communities in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries people had many children; they acted affectionately toward small children although they did not lavish immense attention on them due to alternative obligations. Mothers were primary caretakers, while older sisters, grandmothers, fathers, grandfathers, and other relatives often took a secondary part. People generally indulged boys more than girls, since boys were the link to the future of the family line as well as potential sources of security in old age. Where resources were short, girls might be neglected or even killed at birth if they could not readily be adopted by a wealthier family.[Source: Stevan Harrell, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia — Eurasia / China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

“When children reached the age of 7 or so, there was somewhat of a hardening of attitudes, as indulgence and care gave way to discipline, which meant learning farming or other practical skills and conventional morality for most boys, learning household skills and modesty for most girls, and learning the classical Confucian texts for boys of elite families or aspiring to be of the scholar-elite. From this age on, father-son tensions developed. |~|

Traditional preference for boys seems to be declining. A woman from Shenzhen told The New Yorker blog: “I have an elder brother”. In our case, my parents felt even luckier that I am a girl, because a son and a daughter together forms the character “good.” Another reader said that Chinese attitudes on the boy/girl combo to the French obsession with “le choix du roi.” “The preference for a girl being the elder is that traditionally the big sister is perceived as a more helpful member of the family, who can help to care for the little brother and do family chores,” he writes. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, November 24, 2010]

See Separate Articles:CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; BABIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SURROGATE BIRTHS, FROZEN EGGS AND IN-VITRO TREATMENTS AMONG CHINESE factsanddetails.com ; LITTLE EMPERORS AND MIDDLE CLASS KIDS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHILDREN IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE EDUCATION Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE SCHOOLS Factsanddetails.com/China ; SCHOOL LIFE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINA’S LEFT-BEHIND CHILDREN factsanddetails.com ;

Good Websites and Sources: Busy Kids chinadaily.com. ; Precious Children PBS piece pbs.org Young People ; Sheyla’s News blog /sheylawu.blogspot.com ; Human Trafficking Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery in China gvnet.com International Labor Organization ilo.org/public

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Raising China's Revolutionaries: Modernizing Childhood for Cosmopolitan Nationalists and Liberated Comrades, 1920s-1950s” by Margaret Mih Tillman Amazon.com; “Child Rearing in Rural China” by Jiang Youchun and Yang Yuny Amazon.com; “Love's Uncertainty: The Politics and Ethics of Child Rearing in Contemporary China” by Teresa Kuan Amazon.com; “Understanding the Chinese Personality: Parenting, Schooling, Values, Morality, Relations, and Personality” (1998) by William J. F. Lew Amazon.com; “China's Left-Behind Children: Caretaking, Parenting, and Struggles” by Xiaojin Chen Amazon.com; “Little Emperors: A Year with the Future of China by JoAnn Dionne Amazon.com; “Handbook on the Family and Marriage in China (Handbooks of Research on Contemporary China series) by Xiaowei Zang, Lucy X. Zhao Amazon.com; “Marriage and Family in Modern China (The Library of Couple and Family Psychoanalysis) by David E. Scharff Amazon.com; “Family Life in China (2016) by William R. Jankowiak and Robert L. Moore Amazon.com

Child Customs in China

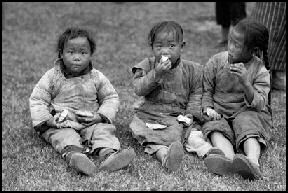

Rural kids in the 1930s

Children often sleep with their parents well into childhood and “alone time” is not something that is emphasized. Christopher Panza, a philosophy professor and expert on Confucianism at Drury University, told the China Daily, “What’s important is that parents do their best to not only to care for the child, but also to develop very close relational ties. From this early age, practices should be set up to the best result in the child developing a very close interdependent bond-servant with the parents.” Chinese kids are so secure that negative remarks often mean little.

"Kaidangku" are pants for toddlers with a slit in the seat that allow a child to relieve himself without removing his paints. Sometimes foreigners are shocked to seem them but many Chinese defend them as comfortable and healthy, plus they make potty training easier. Sex shops sell adult verison of kaidangku that are “transparent, green and charming” and “convenient for you and your partner.”

Chinese put great emphasis on feeding a child. Panza said, “The focus here is not on teaching the child to autonomously feed, but rather to develop an eating ritual that cultivates close ties between the mother (or father) and child.” Spolied kids can often help themselves to cookies, snack food and instant noodles whenever they like.

Chinese parents have traditionally been reluctant to praise their children out of modesty and the fear that pride attracts bad luck. If a Western person tells a Chinese child that he is handsome and smart, it is not unusual for his mother to reply that the child is ugly and stupid, even if he is not.

Children are taught that success is the most important thing. The writer Zhou Changyo told the New York Times, “In America, making your kids happy is the priority and conventional success is secondary. This idea is not acceptable in China. If your child isn’t the best, then he is considered mediocre...It’s not easy for a person to be mediocre in this kind of society.”

See Education

Raising Kids in China

In the old days children were treated well but not spoiled because family members often had other duties and obligations. Mothers were the primary givers, but fathers, grandparents and older sisters helped out. When the children reached 6 or 7, discipline was stressed and boys began studying Confucian texts, and learning farming or some skill while girls were taught about modesty and household chores. These days children are much more spoiled (see Little Emperors Below) and more emphasis than ever is put on education (see Education).

Chinese parents in the opinion of some tend to coddle their children more than Western parents, who are more likely to have their children work out things on their own and sort out their own problems. These days many urban middle class Chinese parents are bucking this trend and sending their kids to day care, keeping the grandparents at arms length and teaching their kids to be independent.One mother in Shenyang with a British husband told the China Daily, “Most Chinese families have grandparents to take care of the children. They love the baby too much and don’t let it experience life for itself, so it can be a bit spoiled and passive. We want an active, independent boy.”

Babies and young children have traditionally been doted upon. Chinese babies as rule seem happy and well behaved and you rarely see them crying. In Shanghai young children are taken to "baby palaces" such as the one next to Jing'an park where children play video games, make paper airplanes, sing Patriotic songs, and color in coloring books. When children become older their socialization becomes stricter. The Chinese have traditionally had few compunctions about beating their children. Parents often send their children to their grandparents while they are growing up.

Eleanor Stanford wrote in “Countries and Their Cultures”: “From a very young age, children are assigned responsibilities in both the family and the community. In the countryside, this means farm chores; in the city, it consists of housework or even sweeping the street. Schoolchildren are responsible for keeping the classroom clean and orderly. Under communism, when women were encouraged to take jobs outside the home, child care facilities became prevalent. Grandparents also play a significant role in raising children, especially when the mother works outside the home. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Busy Chinese Infants and Kids

Leo Lewis wrote in The Times, “Zuming receives a series of one-on-one tutorial sessions every day in a rich variety of brain-expanding disciplines. The boy's parents, grandparents and nanny have all received training to enhance their powers as his auxiliary teachers. About one million renminbi ($150,000) has already been invested in Zuming's education and the next five years of intensive learning have been meticulously planned. He is from Guangzhou and he is almost 12 months old. If Zuming were ever to wonder what the next few years have in store for him, he could seek guidance from his big sister Maiwen's schedule - a packed agenda comprising a normal day of kindergarten followed by extra classes in maths, English, Mandarin, piano and handicrafts. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, January 26, 2013 +++]

Leo Lewis wrote in The Times, “Zuming receives a series of one-on-one tutorial sessions every day in a rich variety of brain-expanding disciplines. The boy's parents, grandparents and nanny have all received training to enhance their powers as his auxiliary teachers. About one million renminbi ($150,000) has already been invested in Zuming's education and the next five years of intensive learning have been meticulously planned. He is from Guangzhou and he is almost 12 months old. If Zuming were ever to wonder what the next few years have in store for him, he could seek guidance from his big sister Maiwen's schedule - a packed agenda comprising a normal day of kindergarten followed by extra classes in maths, English, Mandarin, piano and handicrafts. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, January 26, 2013 +++]

“Only 90 minutes in every 24 hours are not spent sleeping, eating or in some form of education. Her weekends are spent at museums and exhibitions. Having reached the dizzying age of five, Maiwen is about to undergo a private educational assessment that will inform her parents, among other things, what career might ultimately suit her. "I think we will definitely push my son harder than we push the five-year-old," says Amanda Zheng, a highly successful entrepreneur in the clothing industry and the mother of Zuming and Maiwen. "In the end, the boy will have more responsibility to shoulder. We may only let him have 60 minutes' free time every day." Digital Pass $1 for first 28 Days. +++

“The combination of wealth and aspiration has made some Chinese parents easy targets of scams.” In August 2012, “parents in Shanghai were offered a $15,000 course to give children superpowers, such as remembering a whole page of text in a second and knowing the answers to an exam paper by touching it. More than 200 were enrolled before the parents realised they had been conned. Zheng has no such doubts that her money is well spent: "Whether my children want to be an entrepreneur or a flower arranger, they have to be the best possible version of that. Happiness is most important, but that comes later. Now it is important they play the piano perfectly." +++

Social and Economic Forces Behind the Obsessive Studying for Chinese Kids

Leo Lewis wrote in The Times, At the moment, Amanda Zheng, the mother mentioned above, “is primarily investing money and effort to ensure her children are competitive in the domestic context. "But when they are older they will be competing with children everywhere in the world," she says, adding that Western parents should feel concern at the single-mindedness of their Chinese counterparts. "For me, and for a lot of Chinese parents, we think in 20-30-year terms from before they are born - looking at what the world might be like and preparing our children with the qualities they will need," she says. A British education, she believes, offers probably the best "future-proofing" for a Chinese child. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, January 26, 2013 +++]

“Where does the impetus for this educational pressure come from? Zheng unhesitatingly confirms it is definitely her, and not her husband, driving the process. On the face of it, it would be easy to write Zheng and her hothousing tactics off as another education-obsessed Asian matriarch - the implacable, mildly terrifying exemplar of Chinese parenthood introduced to the world in Amy Chua's bestseller, The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mom. But to dismiss what she is doing with her children as a whim of the super-rich or the cruel imposition of an obsessive would be to miss the more fundamental message about what is happening in China. +++

“Zheng is certainly wealthy, and the educational experience of her children is still rare. But her choices are merely a more extreme symptom of a nation undergoing seismic social change on a scale that means there are no comparable experiences anywhere in the world. China's new money is feeling its way just as nervously and ignorantly as it might anywhere else and is - unsurprisingly - susceptible to the idea that more (and the more expensive version) of anything is better. +++

“Among China's swelling middle classes - a stratum of society with a population the size of America that may double by the end of the decade - education for their children is the overwhelming investment priority. They are, supposedly, the great consumers the Chinese and global economy have been waiting for, but by far their strongest impulse has been to spend on anything that sets their offspring apart from the other 20 million Chinese children of the same age. +++

“Already, the reputation of certain good schools in China is creating a bubble market in parental ambitions and vast under-the-table expenditure. Schools with connections to good universities have unofficial price lists of "sponsorship fees" that may help prospective parents get their children in. The system closely resembles bribery. Some schools just name a price in the order of $100,000, say parents; others will ask for donations of facilities such as an entire air-conditioning system. +++

“Overlaid on all that angst is a growing belief among their ranks that the rigid Chinese education system is not nurturing or emphasising the sort of qualities that will ultimately be valuable. "Parents are just as concerned as they used to be, but the thinking has changed a lot in the last two years," Zheng says. "The idea used to be that the answer was to be really strict. Now, more Chinese parents have awoken to different theories, less choices and a type of education that can adapt and react to each child's characteristics." +++

“It is into this cocktail of ambition and doubt that programs of the sort being endured by Zuming and Maiwen have emerged. In their earnest search for the best for their children, parents such as Zheng are particularly attracted to the idea that developed countries have evolved a more scientific approach to education of the very young. Lions, the Chinese company that sells the schemes, is also careful to associate itself with old seats of learning in Britain.” +++

Pressure on Chinese Children

Leo Lewis wrote in The Times: “The pressure on children, say parents across the country, is somewhere between intense and pathological. The great majority of students are only children, forced by China’s strict birth-control laws to carry the onus of family dreams and aspirations single-handed. Piled on top of that is the sheer size of China’s population and the competition created by the stark calculus of ambition. The economy is growing, but not yet generating enough of the good jobs that aspirational Chinese want for their children. Their only rational response is to push them harder. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, December 20, 2013]

“Added to that is the fear that China may be many decades from creating a dependable welfare safety net: until they are convinced otherwise, parents see educated children as their long-term guarantee of healthcare, pension and comfort. With a rote-learning based system, testing is constant and results instantly obvious. Places for good universities were always limited, but the addition of more than 100 million people to the ranks of the middle class over the past decade has made the battle for those places all the more vicious. The consequences are already visible. According to mental health experts, China’s children are hitting their teens without the necessary coping mechanisms. Some dismiss the young as too fragile, others believe they stand no chance against China’s relentless pressure to obey and succeed.

“The reality of China’s school system is often distorted by international comparisons. Mainland Chinese students appear admirably high in the rankings of numeracy and literacy. Other figures present a less cheerful narrative. A recent academic study by British researchers calculated that a third of Chinese children suffer psychological problems from a combination of classroom stress and parental pressure. As China’s ‘‘one-child’’ national birth control policy reaches its 34th year, a generation of only children are entering uncharted territory. They are often cloyingly cherished but burdened with greater expectations than any that have gone before.

“China has reached a point, admit Ministry of Education officials in Beijing, where a single sentence of rebuke from a teacher can be enough to plunge a 12-yearold like Xiaozongzi into the darkest pits of despair. In a text message sent to the boy’s mother by the teacher who told him off, there was bafflement mixed with apology. ‘‘I wanted to come to see you but I don’t know how to face you or what I should say.

“Anything I said would be pale and powerless. Yesterday the boy was so alive in front of me but today we are in two different worlds. God, why did you let this boy die so young?’’ read the text message.

Chinese Children Suicidal Because of School Pressures

Leo Lewis wrote in The Times: “His mother was not back yet, so the 12-year-old let himself into the small ground-floor flat they shared in western Beijing. Programmed to strive and conscientious by nature, Xiaozongzi would normally settle down for a twohour homework session before dinner. Instead, he quietly took the lift to the sixteenth floor, climbed a flight of mouldy concrete stairs to the roof, and threw himself off. A fortnight after his death, the blood of Xiaozongzi — a nickname that oozes parental love and means ‘‘little rice dumpling’’ — remains on the ground where he fell. A dozen small sacks of gravel attempt, ineffectually, to cover it. Residents have been sworn to silence. Those who talk do so nervously and at a distance from the building.[Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, December 20, 2013]

“It is as if something terribly shameful has happened here. Shameful, but not necessarily shocking. As revealed this week in an international comparison of student performances, China may generate the sort of literacy rates and mathematics scores that excite and embarrass British education ministers, but Chinese children and parents know that it all comes at a fearsome cost. The boy’s suicide, say his mother and relatives, was a product of China’s education system — an ultra-competitive, overcrowded environment geared towards discipline and stripped of any real humanity.

“Even veteran teachers, it seems, cannot comprehend what is happening to China’s children. A few days after Xiaozongzi’s plunge on October 23, a 10-year-old boy thousands of miles away in Chengdu took a similar leap from the building where he lived. JunJun had been caught talking in class. He also took his life after a reprimand from a teacher.

After Xiaozongzi’s death, as the rest of the family mounted a roaring protest outside the school, Li retreated to her son’s bed and buried herself in his blankets. Around her were dozens of certificates and awards he had won. The boy was in the top five students in his year. Every day he would finish his homework as soon as he returned from school. He would be allowed to play a little on his computer after dinner, but was always in bed by 8.30pm.

“As they were walking home from school the day before he died, Li says, her son had vowed that he would go to a good university. ‘‘Trust me, mum,’’ he told her, ‘‘if I have a son in the future, he will be the second generation of this family to be rich.’’ On the day of his suicide, Xiaozongzi was messing about with two of his friends — running around with one of them on their shoulders. The boy fell and broke his leg. Before the injured boy was taken to hospital, Xiaozongzi’s mother was called and asked to come to the school. Through the window of his teacher’s office, she saw her son weeping: silently. He looked desperate and wronged, she later said. He was berated by his teacher and made to stand for more than three hours. “He was only allowed home after writing a page of self-criticism.

“Sang Zhiqin, the director of Nanjing University’s Centre of Mental Health Education and Research and an expert on student depression, says that the majority of extreme psychological problems in middle schools were caused by unexpected rebukes from teachers. Children are so on edge, she argues, that small misunderstandings can test them to the limit: ‘‘If students’ ability to cope with frustration is poor and they cannot find a way out, it is easy for them to go to extremes.’’ Nobody will know precisely what drove Xiaozongzi to suicide. “In the narrow lane that leads to the building where he lived and died, another resident offers her theory. ‘The boy’s mother walked him to school every day, and walked him home. She took such care of him. Children like this are not ready for anyone to criticise them,’’ she says quietly.

See Separate Article PROBLEMS WITH THE CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEM factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: 1) Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ ; 2) Baby, Growing up, Beifan.com ; 3) 100 children painting, University of Washington; 4) Rural children, Bucklin archives 5) Adoption, Scafiido Family website ; 6) Baby for sale, Agnes Smedly

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021