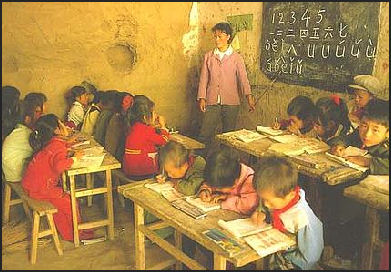

CHINESE SCHOOLS

School in a cave in the Shaanxi Loess Region Nine years of schooling are compulsory, which includes six years of primary school and three years of secondary school. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

China has the world's most primary schools (861,878 in 1993). India has the most secondary schools (241,129 in 1994). Elementary and secondary educational institutions have significantly raised literacy rates and attendance, but schools are hamstrung by financing problems.

Average years of school for people 25 years and older: 3.6 years for females; 6 years for males (Compared to 1.2 years for females and 3.5 years for males in India; and 12.4 years for females and 12.2 years for males in the United States. According to the World Bank 93 percent of Chinese males complete the 5th grade.

A law passed in the 1980s states that every child has the right to nine years in school. Compulsory education ends after the ninth grade. Most kids leave school at that time and before that and look for work or help their family doing agricultural work.

According to government statistics, 95 percent of all children start school but the drop out rate is high. Only 80 percent graduate from elementary school. In poor rural areas the enrollment is only about 60 percent, with only 70 percent completing the first four years of primary school. Fewer than 35 percent of China's youth enter high school, and of these the drop out rate is high.

The schools in the cities are often better than the ones in the countryside. They have an easier time getting government money, teachers and books. The children generally come from families that are better off than there rural counterparts, and money they pay for school expenses helps make the schools better. Schools in major cities typically produce students with strong math and science skills. Rural schools often lack sufficient money, and dropout rates can be high.

Websites and Films About Schools in China

Muslim students with

slate boards “Senior Year” (2005), a film by Zhao Hao, is an in-depth examination of how a class of teenagers prepares for the national college entrance exams in China. When it comes to anxiety about how the U.S compares with other nations, there’s always plenty to go around. But for a real wake-up call, nothing can compare to Zhou Hao’s Senior Year, an in-depth examination of how a class of teenagers prepares for the national college entrance exams that will determine their destinies. Faced with mountains of memorization and rigid behavioral standards, most buckle down, but some rebel and some simply crumble under the pressure. Zhou brings tenderness, humor, and quiet outrage to this rare, behind-the-scenes look at China’s educational system.

“The Village Elementary” (“Changchuan cun xiao”) by new director Huang Mei is a deceptively simple film about rural education and poverty. Huang’s honesty, her respect for her subjects,including a charismatically intellectual, politically aware, but sadly frustrated Sichuanese elementary teacher, gives the film a dirt-poor lyricism that tightly binds the minute details of individual lives to larger issues of political powerlessness and economic dependence.”

Good Websites and Sources: School Life in Beijing bvs-os.de/eigenes/china ; School Life Video YouTube ; Precious Children PBS Show pbs.org/kcts/preciouschildren Center on Chinese Education at Columbia University’s Teacher’s College tc.columbia.edu ; China Today on Chinese Schools chinatoday.com ; Wikipedia article on Chinese Education Wikipedia ; China Education and Research Network (Chinese Government Site) edu.cn/english ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) mclc.osu.edu

See Separate Articles:EDUCATION IN CHINA: STATISTICS, LITERACY, WOMEN AND TEST SCORE SUCCESSES Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEM: LAWS, REFORMS, COSTS factsanddetails.com ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; LITTLE EMPERORS AND MIDDLE CLASS KIDS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCHOOL LIFE IN CHINA: RULES, REPORT CARDS, FILES, CLASSES Factsanddetails.com/China ; VILLAGE SCHOOLS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCHOOL CURRICULUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PROBLEMS AT CHINESE SCHOOLS: CHEATING, EXPLOSIONS AND MYOPIA factsanddetails.com ; TEACHERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PRESCHOOLS AND KINDERGARTEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com THE GAOKAO: THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY ENTRANCE EXAM factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: School Life” “Studying in China: A Practical Handbook for Students” by Patrick McAloon Amazon.com; “Other Rivers: A Chinese Education” by Peter Hessler Amazon.com; “Educating Young Giants: What Kids Learn (And Don’t Learn) in China and America” by N. Pine (2012) Amazon.com; Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to Achieve by Lenora Chu, Emily Woo Zeller, et al. Amazon.com; “Children’s Literature and Transnational Knowledge in Modern China: Education, Religion, and Childhood” by Shih-Wen Sue Chen Amazon.com; “Governing Educational Desire: Culture, Politics, and Schooling in China” by Andrew B. Kipnis Amazon.com; “No School Left Behind” by Wei Gao and Xianwei Liu (2023) Amazon.com ; Preschool: “Preschool in Three Cultures Revisited: China, Japan, and the United States” by Joseph Tobin, Yeh Hsueh, et al. Amazon.com; “Embracing the New Two-Child Policy Era: Challenge and Countermeasures of Early Care and Education in China”by Xiumin Hong, Wenting Zhu, et al. (2022) Amazon.com; Cram Schools: “The Fruits of Opportunism: Noncompliance and the Evolution of China's Supplemental Education Industry” by Le Lin Amazon.com; “Demand for Private Supplementary Tutoring in China: Parents' Decision-Making” by Junyan Liu Amazon.com; Vocational Education: “Class Work: Vocational Schools and China's Urban Youth” by Terry Woronov Amazon.com; “Improving Competitiveness through Human Resource Development in China: The Role of Vocational Education” by Min Min and Ying Zhu Amazon.com

Traditional Chinese Schools

In the old days schools were part of temples and family shrines. In family shrines, the front hall served as a classroom, the rear of the ceremonial hall and the wings on both sides were dormitories.

These traditional Chinese academies were the forerunners today's schools. The provided a place of learning and a place of worship. Teachers and students lived together in the academy. Education emphasized character development as well as the acquisition of knowledge.

See Civil Service Exam, Education

The teacher holds a high position in Confucian traditions. Students are expected to obediently follow their teachers and not question or challenge their authority or knowledge. In the classic Confucian education, students memorized moral precepts in the belief that the precepts would rub off on them. The Communist didn’t like Confucius. They categorized him as a class enemy.

In many ways, the system is a reflection of China’s Confucianist past. Children are expected to honor and respect their parents and teachers. “Discipline is rarely a problem,” said Ding Yi, vice principal at the middle school affiliated with Jing An Teachers’ College. “The biggest challenge is a student who chronically fails to do his homework.”

Students at a modern Confucian school

Confucian Schools

A number of Confucian schools have opened up in recent years. The head of one such school in Shanghai told Reuters, “Parents send their children here mostly because they are keen on Chinese culture. Modern teaching using traditional Chinese methods failed because the schools abandoned the ancient approach to education, which asked students to read, read and read.”

Students spend much of their reciting Confucian classic, with children as young as three memorizing passages of “The Analects”. The father of a 11-year-old at a Confucian school told the Washington Post, “I don’t want my son to be like all those poor kids who have to take exams all the time. My son is more polite after attending this school, and I don’t have to push him to study.”

Describing a Confucian school outside Shanghai, Mark Magnier wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “At the Chrysanthemum Study school...primary school children sit cross-legged at traditional foot-high desks, brush and inkstand at the ready, Their teacher, dressed in a Han dynasty robe with long hanging sleeves, instructs them in Confucian precepts. Respect your parents. Eschew bad habits. Show deference.”

At some universities student are required to take morality and respect for parents classes. For homework students have been asked to wash their parents feet. One student who was asked to do this told the Los Angeles Times, “It think it’s a bit outdated. Parents can go to the foot massage salons themselves if they really want. They don’t need us to do it.”

Chinese Communist Schools

The goal of Communist education policy was to teach the illiterate masses how or read and write, and channel talented young people into science and technology. Recalling school during the Mao era, one man told National Geographic, "In school, mostly we studied about how to farm and be factory workers."

Schools and universities were closed during the Cultural Revolution. See Lost Generation, Crackdown on Intellectuals, Cultural Revolution

In the 1970s, students spent part of each year working in the countryside or on a commune. When the finished middle school they went to a commune or factory to work for two years. After some time the community decided whether the student should go to college or university.

These days elementary school students are taught the importance of achieving a per capita GNP of a developed country by 2050 and told: "We must achieve the goal of modern socialist construction...We must oppose the freedom of the capitalist class, and we must be vigilant against the conspiracy to make a peaceful evolution towards imperialism."

Students in many places are required to carry a card with eight "Student regulations." The first three are: "1) Ardently love the Motherland, support the Chinese Communist Party's leadership, be resolved to serve Socialism's undertaking and serve the people. 2) Diligently study Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought progressively establish a Proletariat class viewpoint, authenticate a viewpoint of Historical Materialism. 3) Diligently study, work, hard to master basic theory, career knowledge, and basic technical ability."

Young Pioneers in China

Young pioneers

The Young Pioneers is the youth branch of the Communist Party. Nearly all students between the second and sixth grades are required to join and wear a red kerchief to school everyday, except when the weather is exceptionally hot and they wear a red pin instead. Eric Eckholm wrote in the New York Times, "Combining elements of the Scouts, the Safety Patrol and the Hall Monitor, larded with thick, simple doses of patriotism and Communism, the Young Pioneers remains a shared experience of China's children.”

Every year, nearly every second grader in China goes through a solemn rite of initiation and becomes a Young Pioneer. Describing the ritual, Eckholm wrote: "Lined up before an audience of classmates, teachers, and perhaps some beaming parents, the school band playing at the side, they stand at attention as sixth-graders march up and place red kerchiefs around heir necks." Older students leads them in the pledge that goes: "I am a Young Pioneer. I pledge under the Young Pioneer flag that I am determined to follow the guidance of the Chinese Communist Party, to study hard, work hard and be ready to devote all my strength to the Communist cause."

Under the supervision of their teachers, the students are organized into teams with the most strait arrow student acting as leaders. One young girl told the New York Times, "As a leader, I have to be a good student, get good grades and be willing to serve the other students. I feel that we have to study hard to build our country stronger."

The students are taught the proper way to raise the flag and salute their superiors; how to dress properly; they read about good deeds performed by model Pioneers. The organization also sponsors summer camps and hobby clubs. Many Chinese look back on their Young Pioneers with a chuckle. Even so many of things that were drilled into them’such as the belief that Tibet and Taiwan are parts of China remains lodged in their brain.

The Communist Youth League is the equivalent of the Young Pioneers for high school students. Most high school students join for social reason and because they are required to. In universities and work places, promising members of the Youth League are chosen to be members of the Communist Party.

Rural Schools in China

A typical rural school is a dirty, whitewashed building made of mud brick and cement. In the classrooms there is no heat or electricity. Light comes from two small windows. There are generally few academic and athletic facilities other than a chalkboard, maybe some desks and chairs and courtyard where children play rough games. Schools are considered well equipped if they have a dirt soccer field.

Describing the classroom for kindergarten class in a small town school, Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, “The classroom was dirty, and there was a hole in the ceiling. The blackboard was chipped and scarred, Twenty children sat at their desks; each of them playing with a pile of Lego-like bricks. There were only three girls.” There was no bathroom. Children relived themselves through the schoolyard fence.

Children from a wide range of ages and abilities often attend the same class. Bright students are often selected by the family to go to school while slow learners have to stay home and help with chores around the house. In rural areas, many children have to walk several miles to their schools.

In villages that have lost their schools due to declining populations as adults have left to find jobs, kids begin boarding at away schools when they are in the first grade and come home only for weekends.

In some villages about only one kid every ten years makes it to college.

Migrant Schools in China

migrant workers school

There are about 20 million migrant children living in Chinese cities. Many of them attend migrant schools that have often been set up by the migrant workers themselves. These schools tend to be basic but are often manned by committed, decent quality teachers. Generally they have lower fees than public schools. Some even have school buses. As of 2005, there were 293 migrant schools in Shanghai. As of 2007 there were about 200 migrant schools in Beijing with 90,000 children.

The first school for migrants to win government approval in Beijing was opened in 1993 by a teacher from a rural school who was shocked to find that many children of migrant workers were basically illiterate because their parents were too busy to help them and because they lacked residency status necessary to attend local schools.

One school was founded in some empty rooms at a market. Describing a classroom in this school Yusaku Yamame wrote in the Asahi Shimbum, “The 50-square-meter classroom with more than 80 students. Children read from their textbook in a loud voice: “A puppy, puppy runs slowly...” The teacher has difficulty even walking around the desks in the room

Shutting Down Migrant Schools, See Migrant Workers, Life

Private Schools in China

Private schools have been allowed in China since the early 1980s. Parents are willing to spend big money to send their children to private schools with good facilities and small teacher to student ratios. In the early 2000s, elite elementary schools in Shanghai cost $1,200 a year and accept only 20 percent of applicants. They are more expensive and take applicants. Private boarding schools like the Guangzhou Country Garden School in Canton charge a one-time tuition payment of $40,000 which is invested by the school and supposed to be returned to parents after graduation. The schools have classes for students of all ages, even preschoolers.

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “The first pre-college private school since the economic reforms was Guangya school in Dujiangyan, Sichuan Province. It opened in June 1992 by Qing Guangya. Three years later there were 20,780 private kindergartens, 3,159 private primary and secondary schools, and 672 private vocational and technical schools. In addition, there were 12,230 private colleges with an average enrollment of 2,400 students. Generally, there have been three types of private schools developed since the 1980s in terms of their funding and operation. The first type was founded and controlled by private investors, including former educators and businessmen. The second type of private schools was set up by Chinese individuals or business firms in collaboration with foreign investors. The third type included those founded and operated by Chinese enterprises and institutions in the tradition of the minban school, which are popularly-run schools supported by village funds in rural areas. Although the majority of minban schools are primary schools, there may be a few middle schools. Many private schools involved government officials or agencies in their administration or boards. In the 1990s, with strong financial support, private schools became much better equipped than most public schools. Computer labs, language labs, indoor gyms, swimming pools, and piano studios have enabled these schools to implement programs that prepared their students for the challenge of the market economy. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

There are also some experimental schools in China. David Barboza wrote in the New York Times, “While Shanghai schools are renowned for their test preparation skills, administrators here are trying to broaden the curriculums and extend more freedom to local districts. The Jing-An school, one of about 150 schools in Shanghai that took part in the international test, was created 12 years ago to raise standards in an area known for failing schools.” “Zhang Renli, creator pf the experimental school that put less emphasis on math and allows children more free time to play and experiment. The school holds a weekly talent show, for example. The five-story school building, which houses Grades eight and nine in a central district of Shanghai, is rather nondescript. Students wear rumpled school uniforms, classrooms are crowded and lunch is bused in every afternoon. But the school, which operates from 8:20 a.m. to 4 p.m. on most days, is considered one of the city’s best middle schools.” A student at Jing’An, Zhou Han, 14, said she entered writing and speech-making competitions and studied the erhu, a Chinese classical instrument. She also has a math tutor. “I’m not really good at math,” she said. “At first, my parents wanted me to take it, but now I want to do it.” [Source: David Barboza, New York Times, December 29, 2010]

More than a thousand Chinese students attend Britain’s top boarding schools. Most arrive at A levels with the aim of getting admitted to one of Britain’s top universities. According to the Times “mainland Chinese are now the second-biggest group of overseas students at British schools, after those from Hong Kong. There are almost 25,000 non-British students, with parents living overseas, at British schools, and nearly 4,000 are from mainland China. “It’s the biggest growth market,” says Ian Hunt, the managing director of Gabbitas, the education consultancy. [Source: Damian Whitworth, Times of London, May 27, 2013]

As China becomes wealthier more and more parents are sending their children abroad to secondary schools, which is often a more expensive endeavor than sending their kids abroad to university. A surprising number of parents shell out the $25,000 in fees to enter British boarding schools. Many are also going to schools in Australia, New Zealand and Canada, where the fees are somewhat lower. In some cases children of corrupt officials are sent abroad to help the officials launder their ill-gotten gains.

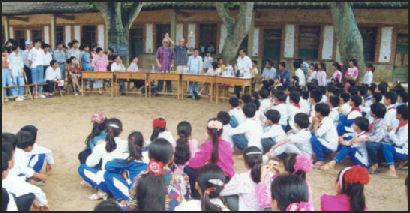

International Schools in China

Assembly at a rural school

According to the Ministry of Education, 256 private and 225 public schools in China provide international education programs for Chinese students who hope to continue their studies abroad. According to the New York Times: These typically offer English or other courses students would need to prepare for foreign universities, instead of courses equipping them to take the gaokao, the Chinese college entrance examination. Many private schools also omit the ideological instruction on Marxism and patriotism that is compulsory in public schools. [Source: Karoline Kan, Sinosphere, New York Times, December 29, 2016]

The International School of Beijing, jointly sponsored by the governments of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the U.K., and the U.S., was established in 1980 as the successor to the former American, Australian, Canadian, and British schools. It is an independent, coeducational day school offering a program ranging from pre-kindergarten through grade 12 for government dependents and other citizens of the founding nations. The curriculum is based on, but not limited to, American models. Language arts and mathematics are emphasized. Social studies, science, computer studies, Chinese, French, art, music, drama, physical education, and health education are also taught. The International Baccalaureate (IB) program is also offered to students in grades 11 and 12, along with several advanced placement courses. All grades meet in regular classes, from self-contained elementary (pre-kindergarten through grade 5) through middle school (grades 6 to 8) to high school (grades 9 to 12). All students study about China within the regular subjects and through special field experiences. There are limited programs for ESL, resource, and English enrichment. [Source: Cities of the World, Gale Group Inc., 2002, adapted from a December 1996 U.S. State Department report]

There are international schools in China’s second and third tier cities as well as first tier ones. Lucy Hornby of Reuters wrote: “The website for a private school in Changzhou, one of China's smaller cities, features blue blazers and plaid skirts, music classes and an ivy-clad brick doorway — all the trappings of the British school system designed to appeal to wealthy Chinese parents. In choosing a smaller city, Oxford International College — no relation to the British university — is tapping into a growing market of upwardly-mobile Chinese willing to pay as much as 260,000 yuan ($41,700) a year for a Western-style education and a ticket to college overseas for their children. "Changzhou is quite an affluent area and many people want to send their kids overseas, so the proportion of Chinese students is ticking up. The expat community is not enough to justify a school," said Frank Lu, the general manager of Oxford International Colleges of China. [Source: Lucy Hornby, Reuters, January 13, 2013]

“That international aura is key to persuading ambitious Chinese parents to pay steep tuition fees. Many schools feature foreign-looking children on their websites or name themselves after elite schools in Britain or North America. Oxford International is one example. Then there is EtonHouse, a Singaporean company that operates schools in eight Chinese provincial cities. Maple Leaf Educational Systems has expanded to seven cities in China from its original home in Dalian, a northeastern Chinese port city, by offering a curriculum endorsed by the British Columbia board of education in Canada. Established British schools like Harrow and Dulwich are also expanding their branches in China.

"My dad wanted me to go abroad at an early age, but my mom did not support the idea," said Jiang Xin, the 17-year old son of a real estate developer, whose parents compromised by sending him to Maple Leaf's Chongqing campus at 50,000 yuan a year. "In the future I want to study abroad. My experience here at Maple Leaf is helping me adapt to the Western learning style earlier." Indeed, many wealthy Chinese parents see these schools as a way to get a foreign-style education while keeping their only children close to home.

“Just under half the international schools in China are in provincial cities like Changzhou, well apart from the main expatriate centers of Beijing, Shanghai or Guangdong. The trend coincides with the increasing incomes of China's middle-classes, who are spread across the country, and their aspirations.

“The international schools in Beijing or Shanghai generally are limited by law to foreign passport-holders. But that's not the case in many provincial cities, where growth in private education including bilingual schools is exploding.Parents who can afford it believe the international schools are the passport to a better life for their children, despite the steeply higher costs. They offer the chance for a university education overseas, avoiding the pressure cooker of the national college entrance exam, taken by more than 9 million Chinese students last June.

Special Education, Reformatories and Schools for the Disabled in China

The 1985 National Conference on Education also recognized the importance of special education, in the form of programs for gifted children and for slow learners. Gifted children were allowed to skip grades. Slow learners were encouraged to reach minimum standards, although those who did not maintain the pace seldom reached the next stage. For the most part, children with severe learning problems and those with handicaps and psychological needs were the responsibilities of their families. Extra provisions were made for blind and severely hearing-impaired children, although in 1984 special schools enrolled fewer than 2 percent of all eligible children in those categories. The China Welfare Fund, established in 1984, received state funding and had the right to solicit donations within China and from abroad, but special education remained a low government priority. [Source: Library of Congress]

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “While the establishment of schools for the physically disabled dates to the late nineteenth century, institutional expansion proceeded moderately until the Cultural Revolution and has increased substantially since the 1980s. In general, however, education for the disabled in China remains in its infancy, and serious improvement remains to be done to promote the social integration of disabled Chinese youth. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“The first Chinese school for the blind and deaf was established in 1927 in Nanjing. After the founding of the PRC in 1949, the Chinese government reaffirmed its commitments to educate the disabled in a 1951 document published by the Ministry of Education. By 1998, there were 1,062 schools for the blind, hearing impaired, and mute, with a total student enrollment of 97,649. There were 21,415 full-time teachers out of a total staff of 30,868. Schools for retarded children date from as late as 1979 and numbered 90 by 1987. The best estimates indicate that 504 schools employ 14,400 special education teachers and staff, who served 52,800 children at the beginning of the 1990. But only six percent of China's 6,000,000 children and youth who suffer from disability are enrolled in any type of educational programs.

“Basically, Chinese special schools only offer a primary-school level education, which emphasizes mastery of survival skills along with those manual skills traditionally performed by adults with specific disabilities. The curriculum follows a work-study structure. The goal of the work experience in these schools is to teach socialization and survival skills. The textbooks used in these schools are the ones used in primary schools with the translations of Braille. Recently, some colleges started to admit disabled students and even established special education majors and teacher training programs devoted to teaching disabled students.

“China established reformatories and work-study schools since the late 1950s and early 1960s when urban and rural theft, fighting, and poor school discipline became noticeable problems. They are under the supervision of the public security apparatus. Based on early Chinese Communist practice in Yanan, reformatories were conceived as production units, and inmate labor would be used to make them self-sufficient and to make them contribute to the socialist economy. Work-study schools for delinquents, on the other hand, were founded for those guilty of less serious delinquent activity. They also emphasized the importance of offenders participating in productive labor. During the Cultural Revolution, the work of both reformatories and work-study schools was disrupted, as reformatories were viewed as overly coercive, and work-study schools were dismissed as ineffective and were shut down completely. During the 1980s when reformatories resumed, the Chinese government still emphasized the use of productive labor as a character-reforming device. Furthermore, the removal of youth from normal family environments, the use of drill and militaristic ritual within the institutional settings, and the display of offenders completing production tasks in public view reinforced the strong negative social labeling that is associated with reformatories and work-study schools. The quality of education provided at both reformatories and work-study schools is often substandard. In addition, they have no systematic counseling system; offenders are put together regardless of their specific offence and few preparations are made to facilitate their readjustment after their release.

Adult and Nonformal Education in China

Because initially only a small percent of the nation's secondary -school graduates were admitted to universities, China found it necessary to develop other ways of meeting the demand for education. Adult education became important in helping China meet its modernization goals. “Adult, or "nonformal," education is an alternative form of higher education that encompasses radio, television, and correspondence universities, spare-time and part-time universities, factory-run universities for staff and workers, and county-run universities for peasants, many operating primarily during students' off-work hours. These alternative forms of education are economical. They seek to educate both the "delayed generation"--those who lost educational opportunities during the Cultural Revolution--and to raise the cultural, scientific, and general education levels of workers on the job. Parttime primary and secondary schools, evening universities, and correspondence schools exist for adult workers and peasants. An educational television network and a TV university are broadcast throughout the country.

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “From 1949 to 1981 the Chinese term for nonformal education was worker-peasant education. After the founding of the People's Republic of China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) launched a campaign to improve worker-peasant literacy for the sake of economic reconstruction. Formal classroom instruction, distance instruction through correspondence, and radio instruction were utilized at factories, production brigades, and government agencies. By 1956, about 62,000,000 peasants had attended different types of literacy classes, representing about 30 percent of the age group of 14 years and older from the country's rural population. To prepare students for college and quickly produce a new kind of intellectual drawn directly from working-class ranks, the CCP also initiated the gongnong sucheng zhongxue (worker-peasant accelerated middle school) experiment in 1950. However, because these schools could not compete with formal educational institutions, and students did not produce good academic records, the experiment was declared a failure and abandoned in 1955.

“The term "adult education" was introduced to China by a study team from the International Council for Adult Education. After the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese government issued its first document regarding adult education on November 6, 1978, titled "Directives on the Issues of Literacy." It set up the standard to eradicate illiteracy among workers and peasants throughout the country; the ability of peasants to master 1,500 Chinese characters and of workers to master 2,000 characters; the capacity to read a newspaper; the ability to write simple letters and complete applications and appropriate forms; and the ability to complete a simple test measuring the above mentioned skills. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“Adult education during the post-Mao period can be characterized by the restoration and re-establishment of institutions abolished during the Cultural Revolution. The 1980s witnessed a radical expansion of higher adult education institutions. Promotion and employment were more directly linked to one's academic rather than political background, increasing the demand for a college diploma. Because of the restrictive admissions policies of formal higher education institutions, the vast majority of high school graduates sought nonformal higher education training. By the end of 1998, approximately 661,705 schools of varied types of nonformal education produced 94,841,000 graduates.

“Nonformal higher education is largely three years in length. It follows the curriculum for formal higher education in corresponding disciplines. Entrance to such programs usually requires passing the Adult Higher Education Entrance Examination, which is a national public examination. The Ministry of Education now includes an adult educational department as do provincial, autonomous regional, municipal, and county-level education commissions, departments, and bureaus.

“In addition to institutional nonformal higher education, open learning through the Self-Study Examination has attracted many candidates. Candidates may enroll in individual subjects and may accumulate their credentials over time. There is no entrance requirement for the self-study examination. The approach was first piloted in three major cities and one province in 1981 and was extended nationwide in 1983. This system was designed to expand the benefits of higher education with minimal investment. It appeals to many adults who do not want to sacrifice their jobs and family life to obtain a college diploma. With no limitation on age and formal education, it opens up higher education to an enormous number of Chinese citizens who would not have had a chance in regular colleges, and inspires great enthusiasm in higher learning.

“The Self-Study Examination is offered twice each year. The National Examination Committee creates the tests, which are administered by local committees. Citizens can apply to take these examinations without having acquired previous course credit. Students who pass the examinations for four-year degree courses receive a bachelor's degree; those who pass three-year courses or single courses are issued certificates. At present, most of the provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions have set up their own local committees for self-study examinations, whose specializations include the liberal arts, science, engineering, agriculture, finance, economics, politics, and law. In the first examination in April 1995, enrollment reached 3.65 million. Of these candidates, 50 percent were students of adult education institutions in one form or another; the other 50 percent had undertaken private study.

Image Sources: Wikicommons; Nolls China website; Columbia University; Beifan.com University of Washington; Bucklin archives ; Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2022