SECONDARY EDUCATION IN CHINA

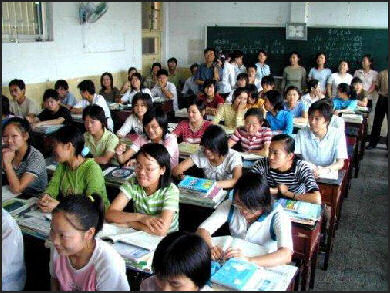

a nice high school in China The Chinese education system provides five years of secondary education for ages 12 to 17. At this level, there are three years of middle school and two years of high school.

Gross enrollment secondary: 88.2 percent (2010). In 2001, about 67 percent of age-eligible children were enrolled in secondary school. The student-teacher ratio in secondary school was about 19 to 1. In the 1990s about 60 percent of Chinese students entered secondary schools but few completed the entire program. [Sources: World Bank datatopics.worldbank.org; Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007

The United Nations Development Programme reported that in 2003 general secondary education in China had 79,490 institutions, 4.5 million teachers, and 85.8 million students. There also were 3,065 specialized secondary schools with 199,000 teachers and 5 million students. Among these specialized institutions were 6,843 agricultural and vocational schools with 289,000 teachers and 5.2 million students and 1,551 special schools with 30,000 teachers and 365,000 students. [Source: Library of Congress, August 2006]

Secondary Educational Enrollment: in 2000: 71,883,000

Educational Enrollment Rate: 70 percent

Teachers: 4,437,000

[Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

In China a senior-middle-school graduate is considered an educated person, although middle schools are viewed as a training ground for colleges and universities. And, while middle-school students are offered the prospect of higher education, they are also confronted with the fact that university admission is limited. Middle schools are evaluated in terms of their success in sending graduates on for higher education, although efforts persist to educate young people to take a place in society as valued and skilled members of the work force. [Source: Library of Congress]

Universities have become overcrowded because many more parents can afford to send their children to secondary school. In 2014, In Nanchong city in Sichuan parents prostrated themselves at the feet of a bureau chief at a local education department where 259 children were vying for 70 places at the best local middle school. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times of London]

See Separate Articles:CHINESE SCHOOLS Factsanddetails.com/China ; EDUCATION IN CHINA: STATISTICS, LITERACY, WOMEN AND TEST SCORE SUCCESSES Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEM: LAWS, REFORMS, COSTS factsanddetails.com ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; LITTLE EMPERORS AND MIDDLE CLASS KIDS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCHOOL LIFE IN CHINA: RULES, REPORT CARDS, FILES, CLASSES Factsanddetails.com/China ; VILLAGE SCHOOLS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCHOOL CURRICULUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PROBLEMS AT CHINESE SCHOOLS: CHEATING, EXPLOSIONS AND MYOPIA factsanddetails.com ; TEACHERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com THE GAOKAO: THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY ENTRANCE EXAM factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: School Life” “Studying in China: A Practical Handbook for Students” by Patrick McAloon Amazon.com; “Other Rivers: A Chinese Education” by Peter Hessler Amazon.com; “Educating Young Giants: What Kids Learn (And Don’t Learn) in China and America” by N. Pine (2012) Amazon.com; Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to Achieve by Lenora Chu, Emily Woo Zeller, et al. Amazon.com; “Governing Educational Desire: Culture, Politics, and Schooling in China” by Andrew B. Kipnis Amazon.com; “No School Left Behind” by Wei Gao and Xianwei Liu (2023) Amazon.com ; Cram Schools: “The Fruits of Opportunism: Noncompliance and the Evolution of China's Supplemental Education Industry” by Le Lin Amazon.com; “Demand for Private Supplementary Tutoring in China: Parents' Decision-Making” by Junyan Liu Amazon.com; Vocational Education: “Class Work: Vocational Schools and China's Urban Youth” by Terry Woronov Amazon.com; “Improving Competitiveness through Human Resource Development in China: The Role of Vocational Education” by Min Min and Ying Zhu Amazon.com

History of Secondary Education in China

Secondary education in China has a complicated history. Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “The First National Conference on Secondary Education was held in Beijing in March 1951. Based on the conference, the Ministry of Education issued the "Temporary Rules for Middle Schools" in the next year. According to this directive, the task of middle schools was to educate a generation of young people for the new China, which meant to combine the theory of Marxism-Leninism with a concrete appreciation for Chinese society and to cultivate proletarian successors who loved the party, the people, and the country. In the early 1950s, a unified system of middle schools was set up in China. All private middle schools were eliminated, and all curriculum and textbooks were standardized. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

In the early 1960s, education planners followed a policy called "walking on two legs," which established both regular academic schools and separate technical schools for vocational training. The rapid expansion of secondary education during the Cultural Revolution created serious problems; because resources were spread too thinly, educational quality declined. Further, this expansion was limited to regular secondary schools; technical schools were closed during the Cultural Revolution because they were viewed as an attempt to provide inferior education to children of worker and peasant families. [Source: Library of Congress]

In the late 1970s, government and party representatives criticized what they termed the "unitary" approach of the 1960s, arguing that it ignored the need for two kinds of graduates: those with an academic education (college preparatory) and those with specialized technical education (vocational). Beginning in 1976 with the renewed emphasis on technical training, technical schools reopened, and their enrollments increased (as did those of key schools, also criticized during the Cultural Revolution). In the drive to spread vocational and technical education, regular secondary-school enrollments fell.

By 1986 universal secondary education was part of the nine year compulsory education law that made primary education (six years) and junior-middle-school education (three years) mandatory. The desire to consolidate existing schools and to improve the quality of key middle schools was, however, under the education reform, more important than expanding enrollment. In 1985 more than 104,000 middle schools (both regular and vocational) enrolled about 51 million students.

The struggle to get into the best universities has led to a struggle to get into the best high schools — the schools that get their students into top university or produce students that score well on the university entrance exam. Some of the best high schools are ones associated with top universities. Students that get into these are also pretty much assured of getting into the affiliated universities as well.

Secondary Schools in China

Chinese secondary schools have traditionally been called middle schools and are divided into junior and senior levels. Junior, or lower, middle schools offered a three year course of study, which students began at twelve years of age. Senior, or upper, middle schools offered a two or three year course, which students began at age fifteen. Some systems have a 4-year junior/3-year senior plan; a few others have a 2-year senior school structure. Secondary schools in China are divided into "key" and "ordinary" schools. [Source: Library of Congress, Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Guanghua school in Wuxi

Rural secondary education has undergone several transformations since 1980, when county-level administrative units closed some schools and took over certain schools run by the people's communes. In 1982 the communes were eliminated. In 1985 educational reform legislation officially placed rural secondary schools under local administration. There was a high dropout rate among rural students in general and among secondary students in particular, largely because of parental attitudes. All students, however, especially males, were encouraged to attend secondary school if it would lead to entrance to a college or university (still regarded as prestigious) and escape from village life.

"Key" (“Keypoint”) schools are relatively well-financed and receive the best students. Admission is often based on an entrance exam taken in the last year of elementary school. In recent years the middle school entrance exam has been officially abolished. In Shanghai there is a lottery system that spreads the best students around to different schools. Some bright students like the ordinary middle schools because they are not so competitive and time consuming and leave the students time to think for themselves and have free time.

Key Schools and Inequality in Chinese Secondary Education

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “Designated key schools are schools distinguished from ordinary schools by their academic reputation and are generally allocated more resources by the state. Their original purpose was to quicken the training of highly needed talent for China's modernization, but another purpose was to set up exemplary schools to improve teaching in all schools. This stratified structure has given key schools numerous privileges. They can select the best students through city-wide or region-wide examination and transfer the best teachers in the area to teach in their school. They receive much more funding from the government, and in getting funds for upgrading equipment or the purchase of expensive items such as computers, they always have priority. Because of these advantages, key schools often boast 90 to 99 percent admission rates to universities (Lin 1999). [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“In addition, key schools dominate the creation and distribution of secondary school education materials. Their best teachers are not only called upon to write and grade national examination test papers, but they are also publishing researchers who authoritatively resolve secondary school disputes through their domination of district education bureau publications. Some key schools are even affiliated with overseas alumni associations that are a source of prestige and hard currency. Such schools embody China's modernization goal of defining success in relationship to international standards. Admission into key schools often paves the way for entering elite colleges in China and abroad, perpetuating a syndrome of ever-increasing pressure on children to gain admission to the best secondary schools. Although the Ministry of Education and local bureaus of education have attempted to reduce student work loads by banning excessive examinations, stipulating the number of hours secondary school pupils must sleep each night, restricting homework during semester breaks and holidays, and preventing merit pay for instructors who teach solely the top students, there is not much improvement.

“Besides inequality between key and ordinary schools, there has been a huge discrepancy between urban areas and less-developed rural areas since the 1980s. Historically, the Chinese government's investment on education for peasants has always been meager. In rural areas 90 percent of secondary schools fail to meet national standards for such basic facilities as chairs, desks, and safe drinking water.

“In 1998, among 13,948 regular senior secondary schools in China, only 20 percent (2,721) were in rural areas, serving 70 percent of Chinese population, not to mention the huge discrepancy in their equipment, government funding, and the quantity and quality of the teachers. In terms of student enrollment, rural pupils only constitute 14 percent (1,310,436) of senior secondary school students (China Statistical Yearbook 1999). Besides inadequate resources, the fact that many peasants believe that formal schooling is useless and irrelevant to their agrarian life is also responsible for the high illiteracy rate in rural areas. The poorest of China's counties are so behind in secondary school provision that the government implemented a prairie fire program to push rural educational efforts (Epstein 1991).

Chinese Secondary School Academics and Exams

The regular secondary-school year usually had two semesters, totaling nine months. In some rural areas, schools operated on a shift schedule to accommodate agricultural cycles. In three-years high schools in China the first year in China is equivalent to the 10th grade in the United States. The academic year for junior secondary school consists of two 20-week terms, 11 to 12 holiday weeks, and one or two weeks for flexible use. Six classes are offered each day, Monday through Friday. Classroom instruction involves 28 to 30 hours each week.

The first year of high school in China is equivalent to the 10th grade in the United States. First year high school students at a top notch school study trigonometry and set theory. Second year students, the equivalent of 11th graders, study things like linear programming. The third and final year of high school is the hardest. One students told the New York Times, there is “endless homework, strict discipline, frequent exams, and per pressure.”

The struggle to get into the best universities has led to a struggle to get into the best high schools — the schools that get their students into top university or produce students that score well on the university entrance exam. Some of the best high schools are ones associated with top universities. Students that get into these are also pretty much assured of getting into the affiliated universities as well.

Secondary School Curriculum in China

Students in middle school and high school study English, chemistry, physics, and law. Vocational schools offer classes in agriculture and industry. First year high school students at a top notch school study trigonometry and set theory. Second year students, the equivalent of 11th graders, study things like linear programming. The third and final year of high school is the hardest. One students told the New York Times, there is “endless homework, strict discipline, frequent exams, and per pressure.”

In the 1980s, The academic curriculum consisted of Chinese, mathematics, physics, chemistry, geology, foreign language, history, geography, politics, physiology, music, fine arts, and physical education. Some middle schools also offered vocational subjects. There were thirty or thirty-one periods a week in addition to self-study and extracurricular activity. Thirty-eight percent of the curriculum at a junior middle school was in Chinese and mathematics, 16 percent in a foreign language. Fifty percent of the teaching at a senior middle school was in natural sciences and mathematics, 30 percent in Chinese and a foreign language. [Source: Library of Congress]

Students in English class listen to a teacher read form a textbook and recite translation about various topics, including American high school drop outs. Even though students often begin studying English when they in the third grade of elementary school they generally can’t really speak the language in high school. The program is geared mainly towards preparing students for the university entrance exams. A 17-year-old student told the Los Angeles Times through an interpreter, “There’s too much focus on grammar and little on actual communication.”

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “The core curriculum of secondary schools includes three fundamental subjects: Chinese, mathematics, and English. Each is taught for six years and together account for more than 50 percent of the total hours students spend in the classroom. Political study is required in each year of secondary school. It consists of political ideology and morality, the history of social development and dialectical materialism, political and legal knowledge, political philosophy, political economy, and review during the senior year. In addition, students study five years of physics, four years of chemistry and biology, three years of geography and history, and one year of computer science, which includes basic computer literacy and programming. Pupils also participate in physical education in each year of secondary school and two or three years of art and music. Many schools now teach typing in the second year of junior secondary school. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Middle School and High School Life in China

dormitory bunkbed

Students in English class listen to a teacher read form a textbook and recite translation about various topics, including American high school drop outs. Even though students often begin studying English when they in the third grade of elementary school they generally can’t really speak the language in high school. The program is geared mainly towards preparing students for the university entrance exams. A 17-year-old student told the Los Angeles Times through an interpreter, “There’s too much focus on grammar and little on actual communication.”

Middle schools and high schools are often located in towns far away from villages. Students from rural areas that want to attend them have to move from their family homes, live in dormitory and visit their families only on the weekends or Sundays. Often they have few friends in their hometowns and their parents treat them like little kids. For the most part their social life is focused around their school. To avoid breaking up their families, the goal of many village parents is to earn enough money or get a new job so they move to a large town or city where there children can receive a secondary education. The dormitories in secondary schools are often packed. In rural Gansu 18 junior high schools girls share a single dormitory room, sleeping shoulder to shoulder like sardines.

High schools have been described a very familial. A group of 40 plus students often stay together and share all the same classes in their first two years and often chose their classes to stay with their friends in their third year. Life is very different than at American high schools. A Chinese Students who attended a high school in Texas told the New York Times, “American high schools are more colorful, more like real life...more complicated.”

Eric Mu wrote in Danwei.com, “My high school life might give you a small glimpse into the real situation: How too much competition poisons people’s relationships, and how when you feel that the guy sitting beside you is your potential enemy who may rob you of a lifetime of happiness, altruism is not going to be your guide. Students hold to themselves and are reluctant to help others. If you have a math question you cannot crack, you keep it to yourself, because all the students are very proprietary about their learning. To offer your knowledge or even your questions for free is not only time consuming but an aid to your enemies. [Source: Eric Mu, Danwei.com September 2, 2011]

I have to say that high school is a monastery and an army boot camp combined. Eleven classes every day. We had to rise before dawn and went to bed after 11. After the last class, we were encouraged to use any bit of extra time for study. There was one student who would go to read his lessons every night in the toilet, because that was the only place where the light would be kept on 24 hours. Everyone hated him, because his breach of a delicate equilibrium that is vital for us to live in peace with each other “he studied just a little too hard. The school encouraged us to be frugal with our time. It had a slogan hanging from the main building: “Time is like water in sponge; if you squeeze harder, there is always more.”

Even though you can always squeeze, even God may need to take a day off every week. For high school students, it was every four weeks. The day was meant for us to go home to pick up some spare clothes and money to sustain us for the next four weeks. But it also offered a rare chance of leisure. One day, think about it, ten hours of freedom, plus undisrupted sleep. How wonderful! I always anticipated the day so much that I kept planning and planning: Going to the bookstore to read the history book that I hadn’t finished? Going to the noodle place in the market to have noodles with lamb soup? When the day eventually came, not a single second passed without causing great anxiety in me like a stingy man counting every penny that he has to shell out.

Top Beijing High School

Alec Ash wrote in The Guardian:“ A tree-lined boulevard led up to Beijing 101’s front entrance, where two guards with truncheons watched over the security gate. Inside, the school buildings glistened in the sun, surrounded by spacious sports grounds and a lake with a goose house and lotus flowers. Students walked around in colour-coded slacks that, like all school uniforms in China, more closely resembled pyjamas: dark blue for year 11, mauve and white for year 12, purple for year 13. The school nestles into the west flank of Beijing’s old Summer Palace – once the relaxation grounds of Qing dynasty emperors – and a back gate connects directly to the garden ruins. Founded in 1946, Beijing 101 was initially set up to educate the children of China’s top officials, and it still has many such students among its ranks. [Source: Alec Ash, The Guardian, October 12, 2016]

“Just a hundred metres down the road from Beijing 101, in the heart of the city’s university district, lies Peking University (or Beida, as it’s known in China). With its illustrious history, roll call of famous alumni and romantic campus dotted with lakes and stone bridges, Beida is the Chinese equivalent of Oxford or Cambridge. Ever since his parents first told him about it as a child, Yuan Qi had always dreamed of going there to study maths. His parents and teachers were encouraging, but even their expectations, he told me, were nothing like the pressure he put on himself.

“When I visited Beijing 101, the scene was not as disciplined as I had expected. School pupils in China — they goof around, joke, talk over each other. At the front gate as I waited to be let in, three boys were lifting up a fourth, giving him a wedgie. Inside was a bulletin board listing extra-curricular activities, from drama to traditional crosstalk comedy performances. A corrugated steel fence next to a basketball court was covered in graffiti, albeit sanctioned by the teachers and expletive-free: V for Vendetta; an alien face with the words “Once I was normal”; “Big Brother is Watching You”, with one of the letters replaced with a swastika. But in class the students quietened down, listened carefully and took notes. In years of reporting in China, I have never heard a single student grumble about their workload. To them, it is simply normal.

Student at a Top Beijing High School

“It was an accomplishment for Yuan Qi to even be there. At his local primary school in Hebei province, there had been 70 to 80 children in each class. The school’s football pitch was never used, as none of the teachers knew the rules. Yuan Qi’s residency papers, or hukou, dictated that he should have stayed in Hebei for middle school, but his father used his connections in the People’s Liberation Army and arranged a transfer to Beijing, with a new hukou. Once there, Yuan Qi enrolled in a better middle school and, thanks to a good performance in the — the — got into Beijing 101 at the age of 16. Yuan Qi was now one step closer to securing his future at the college he dreamed of attending. “In middle school I realised that primary school was easy,” he said. “And in high school I realised that middle school was easy.” [Source: Alec Ash, The Guardian, October 12, 2016]

At Beijing 101, classes had just 20 to 30 students, but the work was twice as intensive as before. As Yuan Qi’s grades were good, he was put into one of four “experimental classes” in his year, which went at an even faster pace. And on top of his regular subjects, like all Chinese students, he also took two hours of politics class each week. They included the compulsory modules of Mao Zedong thought and Deng Xiaoping economic theory, which were introduced in 1991 as part of a patriotic education campaign. I ordered online one of the politics textbooks that Yuan Qi would be studying from. It was titled Integrity of Thought, and a typical page featured a cartoon of three boys sitting around a table discussing the latest government initiatives (as one does), with an accompanying discussion question for students: “What are the everyday applications of these laws?”

Life and Classes at Top Beijing High School

Alec Ash wrote in The Guardian: “The routine at Beijing 101 is punishing. At 6.30am Yuan Qi was out of his dorm bed, and he was in the canteen for breakfast by 6.50. At 7.20 came half an hour of self-study reading time. From 8am he had five 40-minute classes, broken by a half an hour of group calisthenics — a thousand studen — or running around the grounds. Another three afternoon classes were interrupted by five minutes of eye exercises, during which students massaged their tired brows while a recorded track told them to rub behind their ears and press their temples. School broke at 4.05pm, but there was still another three or four hours of homework to be completed before bed. [Source: Alec Ash, The Guardian, October 12, 2016]

“As summer arrived, the pace picked up for Yuan Qi and his classmates. Almost all classes were now spent looking at past gaokao papers in methodical detail. After school, there were two extra hours of mock exams every day, on top of the homework, and five additional classes on Saturday. On Sundays, Yuan Qi’s parents had arranged private tuition for him in English and Chinese. His only relaxation was playing computer games, but whereas in middle school he had enjoyed complex online roleplayers, now he only had time for smartphone apps.

“I sat in on one of Yuan Qi’s classes, a tough but kindly woman walked through exam-paper equations that left me feeling like a dunce. Yuan Qi followed along at his white plastic desk, where sheets covered in intricate geometrical squiggles were sprawled out next to his pencil case and a roll of toilet paper for blowing his nose. At the back of the classroom, a cartoon of Xi Jinping was drawn in coloured chalk on the blackboard next to the words “Wishing you a successful exam” and a reminder: “46 days”. This countdown is a national obsession. If you search for “gaokao” on Baidu, China’s largest search engine, in the months leading up to the exam, an image appears at the top of the results page, with a clock counting down to the start of the exam, next to a cartoon of a schoolgirl riding a flying book.

End of High School in China

Eric Mu wrote in Danwei.com, “Three years of running this strenuous marathon. The inevitable climax was more of an anticlimax. The test didn’t turn out to be as I had imagined it — a grand battle. I had been seeing myself on stage, with a war bugle blowing and bullets whizzing by and here I was, a soldier crouching in his trench and ready for a bayonet charge, to take my fate by its throat. The reality was much duller though. A room packed with 40 students huddling in front of their small desks, under the scrutiny of a surveillance cam and two chatty supervisors. We were no warriors but prisoners. If we were fighting for anything, it was just for our own survival. [Source: Eric Mu, Danwei.com September 2, 2011]

During the few days prior to the exam, some interesting changes took place. My head teacher seemed to have a personality transplant. He appeared to be a different person. He was now such a nice guy that I barely recognized him. In our final class, he gave us his goodbye speech. He told us how pleasant it had been working with us for the past three years, that he had been proud of us and would never forget us. I had been thinking the exact opposite — that we were the worst class he had ever taught and that he had always hated us “particularly me, the sullen mean type who just won’t cooperate “and wanted to wipe us from from his memory as soon as we are gone.

He proceeded with his emotion-charged speech. “If I ever hurt any of you, it was not my intention. As a teacher , I always had my students’ best interests in mind.” Some girls were moved to cry. “One day as a teacher, a life as a father,” he quoted an ancient saying, which gave me a feeling of embarrassment for the hypocrisy. All theatrics aside, the message was clear to me: “I know I abused you but I don’t want to be hated. Now, as you are about to leave, there is no point for me to be harsh any more. What can be done can’t be undone, and it is all the past, so let’s move on and forget it and be friendly to each other.”

“I love you.” was the signal for the end of the speech, a rather clichéd wrap-up. “We love you too.” The students yelled back. Liars! But a ritual like this worked. Reconciliation was achieved. Damages were forgiven. Grudges healed. Even I, the most foolhardy, unrelenting hater, felt that it might not be fair to blame the guy for his offensive remarks about me. He was, after all, doing his job.

Vocational Schools in China

Middle school class In addtition senior secondary schools that prepare students for going on to college, there are vocational and technical senior secondary schools (VTE) that train pupils in specialized fields and prepare them to enter the workforce immediately after graduation from secondary school. Both regular and vocational secondary schools were initially conceived by the Communists to serve modernization needs. A number of technical and "skilled-worker" training schools reopened after the Cultural Revolution, and an effort was made to provide exposure to vocational subjects in general secondary schools (by offering courses in industry, services, business, and agriculture). By 1985 there were almost 3 million vocational and technical students. [Source: Library of Congress]

Tuition is free in vocational secondary schools and in training schools for elementary teachers. Under the educational reform tenets, polytechnic colleges were to give priority to admitting secondary vocational and technical school graduates and providing on-the-job training for qualified workers. Education reformers continued to press for the conversion of about 50 percent of upper secondary education into vocational education, which traditionally had been weak in the rural areas. Regular senior middle schools were to be converted into vocational middle schools, and vocational training classes were to be established in some senior middle schools. Diversion of students from academic to technical education was intended to alleviate skill shortages and to reduce the competition for university enrollment.

In 1987 there were four kinds of secondary vocational and technical schools: technical schools that offered a four year, post-junior middle course and two- to three-year post-senior middle training in such fields as commerce, legal work, fine arts, and forestry; workers' training schools that accepted students whose senior-middle-school education consisted of two years of training in such trades as carpentry and welding; vocational technical schools that accepted either junior-or senior-middle-school students for one- to three-year courses in cooking, tailoring, photography, and other services; and agricultural middle schools that offered basic subjects and agricultural science.

These technical schools had several hundred different programs. Their narrow specializations had advantages in that they offered in-depth training, reducing the need for on-the-job training and thereby lowering learning time and costs. Moreover, students were more motivated to study if there were links between training and future jobs. Much of the training could be done at existing enterprises, where staff and equipment was available at little additional cost.

According to the New York Times: “China’s vocational secondary schools and training programs are unpopular because they are seen as dead-ends, with virtually no chance of moving on to a four-year university. They also suffer from a stigma: they are seen as schools for people from peasant backgrounds, and are seldom chosen by more affluent and better-educated students from towns and cities. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, January 24, 2013]

Vocational School Education in China

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “Full-time senior secondary school programs are commonly classified into specialized technical and teacher-training schools, technical and pre-service skilled worker schools, and, the largest sector, vocational and agricultural schools. The most prestigious VTE programs are offered by more than 4,109 specialized schools that train middle-level technical personnel and kindergarten and primary school teachers. These institutions, developed in the mid-1950s and directed by technical ministries as well as the Ministry of Education, are managed directly by education, technical, and labor bureaus at the local, district, county, and provincial levels. Entering students are junior secondary school graduates who are selected through competitive state examinations administered by bureaus of higher education. The four-year study program includes nine broad specializations in technical fields (agriculture, art, economics, engineering, forestry, medicine, physical culture, politics and law, and a miscellaneous category that includes everything from the training of Buddhist monks and nuns to flight attendants) and one type in teacher training for secondary schools. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“Less prestigious than specialized schools, technical schools are run by education bureaus and industrial units. They train technicians in steel, textile, petroleum, pharmaceutical, agricultural, and botanical enterprises, as well as middle-level workers in law, finance, health, art, and physical culture. These primarily three-year institutions recruit junior middle school graduates who are assigned to them by labor and personnel bureaus on the basis of entrance examination results and preferred choice of specialty. They are more successful than specialized schools in forging close and flexible ties with specific enterprises because their enrollment and curriculum are not controlled by national ministries. Like specialized schools, they have the advantage of high demand since students receive employment upon graduation.

“Key and non-key vocational and agricultural schools, normally managed at the district and county level, have offered the least prestigious VTE programs because their graduates have not enjoyed secure employment opportunities and because graduates from these three-year programs are classified as skilled workers rather than technicians. Therefore, they provide the last chance for students hoping to pursue senior secondary schooling and have the highest level of dropouts. However, vocational and agricultural schools in relatively developed regions of China have managed to compensate for the lack of formal employment mechanisms by powerful local contacts with surrounding enterprises and capitalizing on economic demand for skilled labor. Job security, in turn, has raised the confidence of the public in such schools, which are attracting increasingly qualified junior high school graduates.

Chinese High School Students Hold Principal Hostage

“Protesting students held a school principal hostage over fears their degrees would be devalued. The BBC reported: The protests were over a plan to merge a Nanjing college in Jiangsu province with a vocational institute — which are seen as less prestigious. Some of the students were reportedly injured as police allegedly used batons and pepper spray on them. [Source: BBC, June 9, 2021]

Danyang city police said in a statement on Tuesday that undergraduates at Nanjing Normal University's Zhongbei College in Jiangsu province had "gathered" from Sunday and detained the 55-year-old principal on campus for more than 30 hours. Students "shouted verbal abuse and blocked law enforcement", and refused to let him leave even after authorities announced a suspension of the merger plans, the statement added.

“Social media users posted photos of police using batons and pepper spray on students, and one female undergrad bleeding from the head, the AFP, news agency said. The police statement said "to uphold campus order... public security organs took necessary measures in accordance with the law to remove the trapped person, and (the injured) were immediately sent to hospital for treatment.

“All six colleges in Jiangsu province have since said that they would suspend any merger plans. “The Jiangsu Education Department had said the decision was to comply with a Ministry of Education directive to transform independent colleges into vocational schools. The decision has led to protests in four other independent colleges in the province in recent days over similar fears, with "some events of physical confrontation" according to the Global Times newspaper.

“Independent colleges are co-funded by universities and social organisations or individuals. Students who do not get the required exam scores to enter university can apply to these institutions, where they can still graduate with a university degree — but at higher tuition costs. These degrees are seen as more prestigious than vocational degrees, and graduates believe they offer them better opportunities in the country's fiercely competitive job market.

Image Sources: Wikicommons; Nolls China website; Columbia University; Beifan.com University of Washington; Bucklin archives ; Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2022