ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA

In 1979, three years after Mao’s death, a one-child policy was introduced to control China’s exploding population, help raise living standards and reduce the strain on scarce resources. The policy has been credited with preventing 400 million births and keeping China’s population down to its current 1.4 billion by cutting the birth rate per family from 2.9 children in 1979 to 1.6 in 1995 but to achieve that goal heavy fines and forced abortions and sterilizations were employed.

In 1979, three years after Mao’s death, a one-child policy was introduced to control China’s exploding population, help raise living standards and reduce the strain on scarce resources. The policy has been credited with preventing 400 million births and keeping China’s population down to its current 1.4 billion by cutting the birth rate per family from 2.9 children in 1979 to 1.6 in 1995 but to achieve that goal heavy fines and forced abortions and sterilizations were employed.

Under the one-child program, a sophisticated system rewarded those who observed the policy and penalized those who did not. Couples with only one child were given a "one-child certificate" entitling them to such benefits as cash bonuses, longer maternity leave, better child care, and preferential housing assignments. In return, they were required to pledge that they would not have more children. In the countryside, there was great pressure to adhere to the one-child limit. Because the rural population accounted for approximately 60 percent of the total, the effectiveness of the one-child policy in rural areas was considered the key to the success or failure of the program as a whole. [Source: Library of Congress]

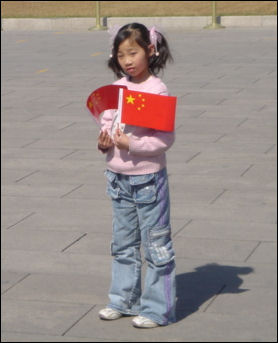

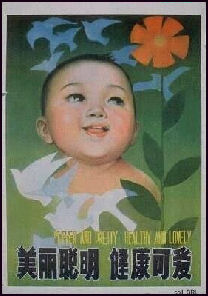

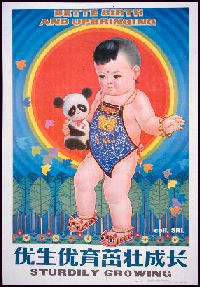

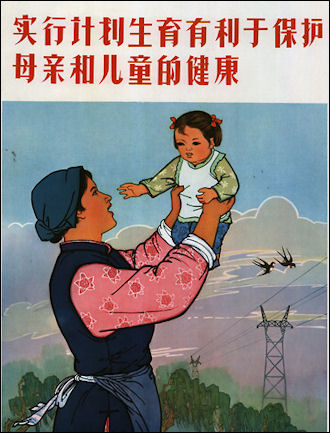

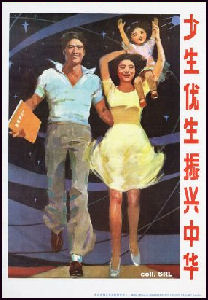

In the 1980s, 90s and 2000s posters promoting China's one-child policy could be seen all over China. One, with the slogan "China Needs Family Planning" showed a Communist official praising the proud parents of one baby girl. Another one, with the slogan "Late Marriage and Childbirth were Worthy," showed an old gray-haired woman with a newborn baby. Others read: “Have Fewer, Better Children to Create Prosperity for the Next Generation” and "Have less children, have a better life" Slogans such as “Have Fewer Children Live Better Lives” and "Stabilize Family Planning and Create a Brighter Future” were painted on roadside buildings in rural areas. Some crude family planning slogans such “Raise Fewer Babies, But More Piggies” and “One More Baby Means One More Tomb” and "If you give birth to extra children, your family will be ruined" were banned in August 2007 because of rural anger about the slogans and the policy behind them.

By the mid 2000s, China’s birth-planning laws allowed so many exceptions that many demographers considered it a misnomer to call it a “one-child” policy. Families where both parents were only children could have an extra child. People in rural areas were also allowed to bear a second child if their first child was a girl or disabled. Ethnic minorities were allowed more children. According to the policy as it was most commonly enforced at that time, a couple was allowed to have one child. If that child turned out be a girl, they were allowed to have a second child. After the second child, they were not allowed to have any more children. If they did they were fined. In some places, couples were only allowed to have one child regardless of whether it was a boy or a girl. It was still unusual for a family to have two sons.

The one-child policy actually only covered only about 35 percent of Chinese, mostly those living in urban areas. The conventional wisdom in China was that controlling China's population served the interest of the whole society and that sacrificing individual interests for those of the masses was justifiable. The one-child policy was introduced around the same time as the Deng economic reforms. An unexpected result of these reforms was the creation of demand for more children to supply labor to increase food production and make more profit.

Good Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article on the One Child Policy Wikipedia ; Family Planning in China china.org.cn ; Christian Science Monitor article on Too Many Boys csmonitor.com ; National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China stats.gov.cn; Trends in Chinese Demography afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Institute of Population and Labor Economics cass.cn Links in this Website: SERIOUS PROBLEMS WITH THE ONE-CHILD POLICY: factsanddetails.com ; END OF THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; POPULATION IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; BIRTH CONTROL IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; PREFERENCE FOR BOYS Factsanddetails.com/China ; THE BRIDE SHORTAGE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “One Child” (2017) by Mei Fong Amazon.com; “Just One Child: Science and Policy in Deng’s China” by Susan Greenhalgh Amazon.com; “China's Hidden Children: Abandonment, Adoption, and the Human Costs of the One-Child Policy” by Kay Ann Johnson (2017) Amazon.com; “China's One-Child Policy: The Government's Massive Crime Against Women and Unborn Babies” by Committee on Foreign Affairs House of Representatives Amazon.com; “Secrets and Siblings: The Vanished Lives of China’s One Child Policy” by Mari Manninen and Mia Spangenberg Amazon.com; “Mother's Ordeal: One Woman's Fight Against China's One-Child Policy” by Steven W. Mosher Amazon.com; “Forced abortion and sterilization in China:” The view from the inside : hearing before the Subcommittee on International Operations and Human Rights of the U.S. Congress (1998) Amazon.com; “China's One-Child Policy and Multiple Caregiving: Raising Little Suns in Xiamen” by Esther Goh Amazon.com; “China's Low Fertility and the Impacts of the Two-Child Policy” by Wei Chen Amazon.com; “Embracing the New Two-Child Policy Era: Challenge and Countermeasures of Early Care and Education in China”by Xiumin Hong, Wenting Zhu, et al. (2022) Amazon.com “From One Child to Two Children: Opportunities and Challenges for the One-child Generation Cohort in China” by Shibei Ni Amazon.com;

Was the One-Child Policy Successful as Claimed

Some have said the the one-child policy was spectacularly successful in reducing population growth, particularly in the cities (reliable figures are harder to come by in the countryside). In 1970 the average woman in China had almost six (5.8) children. By the 1990s the figure was around. The most dramatic changes took place between 1970 and 1980 when the birthrate dropped from 44 per 1000 to 18 per 1,000. Demographers have stated that the ideal birthrate rate for China is 16.7 per 1,000, or 1.7 children per family.

While it had many drawbacks, the One-Child Policy created an age structure that helped the the economy boom from the 1980s to the 2010s: The large working-age population born before and after it grew rapidly compared to the country’s younger and older dependent population. This “demographic dividend” accounted for 15 percent of China’s economic growth between 1982 and 2000, according to a 2007 United Nations working paper. [Source: Lihong Shi, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Case Western Reserve University, The Conversation, September 26, 2021]

Some have argued that economic prosperity and other social and economic conditions did as much as the one-child policy to shrink population growth. As costs and the expense of having children in urban areas rose, and the benefits of children as a labor sources shrunk and thus many couples opted not to have children. Susan Greenhalgh, a China policy expert at the University of California in Irvine, told Reuters, “Rapid socioeconomic development has largely taken care of the problem of rapid population.” Taiwan, Japan and South Korea, have lower birthrates without coercive measures, as people marry later and move into smaller homes. In South Korea and Thailand the average number of children per mother plunged from above six in the 1960s to below three by 1980, according to the World Bank. Birthrates are also very low in Europe, where strong coercive measures to reduce births have not been used.

Even without state intervention, there were compelling reasons for urban couples to limit the family to a single child. Raising a child required a significant portion of family income, and in the cities a child did not become an economic asset until he or she entered the work force at age sixteen. Couples with only one child were given preferential treatment in housing allocation. In addition, because city dwellers who were employed in state enterprises received pensions after retirement, the sex of their first child was less important to them than it was to those in rural areas. [Source: Library of Congress]

Did the One-Child Policy Really Prevent 400 Million Births

Chinese officials said the one-child policy prevented 400 million births, the equivalent of the population of Europe. The reduction of population has helped pull people out of poverty and been a factor in China’s phenomenal economic growth. One way the government records progress in its birth control programs was by monitoring the "first baby" rate — the proportion of first babies among total births. In the city of Chengdu in Sichuan for a while the first baby rate was reportedly 97 percent.

In a paper published in the journal Demography in August 2017, Daniel Goodkind—an analyst at the U.S. Census Bureau in Suitland, Maryland, who published as an independent researcher—argued that China’s 400 million averted birth figure has merit. Mara Hvistendahl wrote in Science Magazine: “By extrapolating from countries that experienced more moderate fertility decline, Goodkind contends that birth-planning policies implemented after 1970 avoided adding between 360 million and 520 million people to China’s population. Because the momentum from that decline will continue into later generations, he suggests, the total avoided population could approach 1 billion by 2060. Some scholars worry such estimates could be used to justify, ex post facto, the policy’s existence. [Source: Mara Hvistendahl, Science Magazine, October 18, 2017]

The 400 million averted births figure "originated in a 1990s analysis by China’s National Population and Family Planning Commission, the agency that implemented the one-child policy. To estimate what fertility might have been without the policy, commission researchers simply extended the trajectory of fertility decline between 1950 and 1970 to the following decades, arriving at a crude birth rate of 28.4 per 1000 people by 1998. They compared this with China’s actual birth rate that year, 15.6 per 1000 people, and projected how many more babies would have been born. Three demographers—Wang Feng of the University of California, Irvine; Cai Yong of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill; and Gu Baochang of Renmin University of China in Beijing—set out to challenge this figure. In a 2013 paper in Population and Development Review, they found that in 16 developing countries that started with similar birth rates as China in 1970, the crude birth rate fell to an average of 22 per 1000 by 1998, far below the commission’s estimate. They did not use this method to provide a better estimate of how many births the one-child policy avoided because of the risk of inaccuracy and misinterpretation, they say. “In his paper, Goodkind takes that step. He compares China’s actual population with that implied by the pace of fertility decline in those 16 countries, along with Vietnam and India. In the absence of birth regulations, he concludes, the average Chinese woman since 1990 would have had two children." The rate in 2020 was 1.3.

Population Control in China Under Mao

Mao Zedong, the leader of China from 1949 to 1976, did nothing to reduce China's expanding population, which doubled under his leadership. He believed that birth control was a capitalist plot to weaken the country and make it vulnerable to attack. He liked to say, "every mouth comes with two hands attached." For a while Mao urged Chinese to have lots of children to support his “human wave” defense policy when he feared attack from the United States and the Soviet Union.

The novelist Ma Jian wrote in The Guardian:“In China, procreation and childbirth are, like every facet of human life, deeply political. Since the Communist party came to power in 1949, it has viewed the country's population as a faceless number that it could increase or decrease as it chooses, not a society of individuals with unique desires and inviolable rights. At first, Mao Zedong encouraged large families and outlawed abortion and the use of contraception, urging women to produce offspring who would boost the workforce and the ranks of the People's Liberation Army. My mother dutifully gave birth to five children. Our neighbour, Mrs Wang, produced 11, and was declared a "Heroine Mother" by the local authorities and given a large red rosette to pin to her lapel. Mao's reckless strategy caused China's population to double from about 500 million in 1949 to almost a billion three decades later.[Source: Ma Jian, The Guardian, May 6, 2013]

Soon after taking power in 1949 Mao declared: “Of all things in the world, people were the most precious.” He condemned birth control and banned the import of contraceptives. He then proceeded to kill lots of people through vicious crackdowns on landlords and counter-revolutionaries, through the use of human-wave warfare in North Korea and through failed experiments like the Great Leap Forward.

In the 1970s Mao began to come around to the threats posed by too many people. He began encouraged a policy of “late, long and few” and coined the slogan: “One was good, two was OK, three was too many.” In the years after his death, China began experimenting with the one-child policy. In 1972 and 1973 the party mobilized its resources for a nationwide birth control campaign administered by a group in the State Council. Committees to oversee birth control activities were established at all administrative levels and in various collective enterprises. This extensive and seemingly effective network covered both the rural and the urban population. In urban areas public security headquarters included population control sections. In rural areas the country's "barefoot doctors" distributed information and contraceptives to people's commun members. By 1973 Mao Zedong was personally identified with the family planning movement, signifying a greater leadership commitment to controlled population growth than ever before. Yet until several years after Mao's death in 1976, the leadership was reluctant to put forth directly the rationale that population control was necessary for economic growth and improved living standards.

The "Later, Longer, Fewer" policy that was the cornerstone of China's birth control program was put into effect in 1976, around the same time that Mao died. It encouraged couples to get married later, wait longer to have children, and have fewer children, preferably one. The program forced married couples to sign statements that obligated them to one child. Women who had abortions were given free vacations.

Birth Patterns Before the One-Child Policy

Over time the liabilities of a large, rapidly growing population soon became apparent. For one year, starting in August 1956, vigorous propaganda support was given to the Ministry of Public Health's mass birth control efforts. These efforts, however, had little impact on fertility. After the interval of the Great Leap Forward, Chinese leaders again saw rapid population growth as an obstacle to development, and their interest in birth control revived. In the early 1960s, propaganda, somewhat more muted than during the first campaign, emphasized the virtues of late marriage. Birth control offices were set up in the central government and some provinciallevel governments in 1964. The second campaign was particularly successful in the cities, where the birth rate was cut in half during the 1963-66 period. The chaos of the Cultural Revolution brought the program to a halt, however. [Source: Library of Congress]

According to Chinese government statistics, the crude birth rate followed five distinct patterns from 1949 to 1982. It remained stable from 1949 to 1954, varied widely from 1955 to 1965, experienced fluctuations between 1966 and 1969, dropped sharply in the late 1970s, and increased from 1980 to 1981. Between 1970 and 1980, the crude birth rate dropped from 36.9 per 1,000 to 17.6 per 1,000. The government attributed this dramatic decline in fertility to the wan xi shao (later marriages, longer intervals between births, and fewer children) birth control campaign.

However, elements of socioeconomic change, such as increased employment of women in both urban and rural areas and reduced infant mortality (a greater percentage of surviving children would tend to reduce demand for additional children), may have played some role. To the dismay of authorities, the birth rate increased in both 1981 and 1982 to a level of 21 per 1,000, primarily as a result of a marked rise in marriages and first births. The rise was an indication of problems with the one-child policy of 1979. Chinese sources, however, indicated that the birth rate decreased to 17.8 in 1985 and remained relatively constant thereafter.

In urban areas, the housing shortage may have been at least partly responsible for the decreased birth rate. Also, the policy in force during most of the 1960s and the early 1970s of sending large numbers of high school graduates to the countryside deprived cities of a significant proportion of persons of childbearing age and undoubtedly had some effect on birth rates.

Primarily for economic reasons, rural birth rates tended to decline less than urban rates. The right to grow and sell agricultural products for personal profit and the lack of an oldage welfare system were incentives for rural people to produce many children, especially sons, for help in the fields and for support in old age. Because of these conditions, it was unclear to what degree propaganda and education improvements had been able to erode traditional values favoring large families

Early Years of the One Child Policy

Ma Jian wrote in The Guardian:““ By the time Deng Xiaoping took over the reins in 1978 after the calamitous cultural revolution, not only was Mao dead, but so was all faith in communist ideology. Deng knew that for the party to regain legitimacy, it would have to achieve economic growth, and a small group of technocrats, headed by rocket scientist Song Jian, persuaded him that for China to meet its economic targets for the year 2000, its population would have to be restricted to 1.2 billion. The one-child policy they proposed was swiftly introduced: couples in China could have only one child, or in the countryside two if the first child was a girl. The production of children became as subject to state targets and quotas as the production of grain and steel.[Source: Ma Jian, The Guardian, May 6, 2013 ^*^]

From the late 1970s to the early 1980s, China’s family planning policy evolved from “One couple two children,” to “One couple better one child,” and then to “One couple only one child.” From advocating “One couple one child” the government moved to punishing parents who have more than one child. In 1988, the “one-child policy” became a little more flexible, to allow couples in rural areas with one daughter to have a second child with planned spacing. [Source: Zhonghua Renmin Gonghe Guo, Fang-fu Ruan, M.D., Ph.D., and M.P. Lau, M.D. Encyclopedia of Sexuality hu-berlin.de/sexology =]

According to the Encyclopedia of Sexuality: China’s population policy consisted of two components: decreasing and limiting the quantity of population; and improving the quality of population. To reduce the numerical growth of the population, three main measures were practiced: late marriage, late childbearing, and fewer births - the “one-couple-one-child policy.” The basic measure used to improve the quality of the population involved efforts to prevent birth defects. The dual population policy proved to be effective: China had 200 million fewer babies born in 1988 than in 1970. The result was a saving of 3 trillion yuan ($802 billion). During the 1960s, the average Chinese woman gave birth 5.68 times (the figure included infant deaths, still births, and abortions). This dropped to 4.01 during the 1970s and to 2.47 in the 1980s. The average population growth rate dropped from 2.02 percent during the period from 1949 to 1973 to 1.38 percent from 1973 to 1988. =

According to a survey in early 1990s, 66.2 percent of married urban respondents said that they accepted the one child policy and 28.5 percent said they thought such restrictions were unreasonable. If they had only a daughter, 35.5 percent said they wanted another child, but not if they incurred punishment from the government. Most rural couples said they wanted a boy and a girl, but 48.5 percent said they would accept having only one child. After having a daughter, 60.3 percent wanted an additional child, and 6 percent still want one at the risk of sustaining some official penalty. In a 1989 survey, 68.1 percent of rural women wanted two children, 25.7 percent wanted one child, and 3.1 percent did not want children. Slightly lower percentages were found among rural men. [Source: “1989-1990 Survey of Sexual Behavior in Modern China: A Report of the Nationwide “Sex Civilization” Survey on 20,000 Subjects in China: by M.P. Lau’, Continuum (New York) in 1997, Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review (1995, volume 32, pp. 137-156), Encyclopedia of Sexuality hu-berlin.de/sexology ++]

Family Planning and Population Control Bureaucracy in China

The National Population and Family Planning Commission ran the one-child policy and monitored the child bearing habits of the Chinese masses. It was comprised of 300,000 full-time paid family-planning workers and 80 million volunteers, who were notorious for being nosey, intrusive and using social pressure to meet its goals and quotas. Chinese women had to obtain a permit to had a child. If a woman was pregnant and she already had children she was often pressured into having an abortion. Special bonuses were given to men and women that had their tubes tied. Local officials were often evaluated in how well they meet their population quotas. Communist Party cadres could be denied bonuses and blocked from promotions if there were excess births in their jurisdictions.

The National Population and Family Planning Commission ran the one-child policy and monitored the child bearing habits of the Chinese masses. It was comprised of 300,000 full-time paid family-planning workers and 80 million volunteers, who were notorious for being nosey, intrusive and using social pressure to meet its goals and quotas. Chinese women had to obtain a permit to had a child. If a woman was pregnant and she already had children she was often pressured into having an abortion. Special bonuses were given to men and women that had their tubes tied. Local officials were often evaluated in how well they meet their population quotas. Communist Party cadres could be denied bonuses and blocked from promotions if there were excess births in their jurisdictions.

“In rural areas the day-to-day work of family planning was done by cadres at the team and brigade levels who were responsible for women's affairs and by health workers. Every village had a family planning committee and in some, women of childbearing age were required to had pregnancy tests every three months. In the 1980s the women's team leader made regular household visits to keep track of the status of each family under her jurisdiction and collected information on which women were using contraceptives, the methods used, and which had become pregnant. She then reported to the brigade women's leader, who documented the information and took it to a monthly meeting of the commune birth-planning committee. According to reports, ceilings or quotas had to be adhered to; to satisfy these cutoffs, unmarried young people were persuaded to postpone marriage, couples without children were advised to "wait their turn," women with unauthorized pregnancies were pressured to had abortions, and those who already had children were urged to use contraception or undergo sterilization. Couples with more than one child were exhorted to be sterilized. [Source: Library of Congress]

At the bottom of the bureaucracy were millions of neighborhood committees which had to answer to the next level up, the street or village committees. In the cities, several street committees make up a district committee which in turn were under the jurisdiction of the Municipal People's government or the Regional People's government. All of these committees follow birth control guidelines laid out by the Central Chinese government.

If neighborhood, street or village committees were unsuccessful in dissuading a couple from having a child, community "units" at the husband's and wife's work place were called in to pressure the couple, sometimes by reducing wages, taking away bonuses or threatening unemployment. Community units were also called in if a couple was thinking about getting divorced.

Family Planning Officials

The officials who work in the local family offices were often members of the Communist Party. They had broad powers to order abortions and sterilizations and impose heavy fines euphemistically called ‘social service expenditures,” which were often important sources of income for local governments in rural areas. Couples were supposed to get a permit before they even conceive a child. To be eligible couples must had a marriage certificates and had their residency permits in order. Women must be at least 20 and men 24. Old legal scholar in Beijing told the Los Angeles Times, “the family planing people were even more powerful than the Ministry of Public Security.”

Kenneth R. Weiss wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Those who work for the vast family planning bureaucracy take great pride in what they see as their contributions to China's prosperity. In discussing the country's population policies, the giddy bureaucrats turned again and again to the economic rewards. "We want to get rich before we get old," was a common refrain. [Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012 \=/]

Yu Xuejun, a director-general in the country's National Population and Family Planning Commission, told the Los Angeles Times that the policy had caused hardships. "I myself sacrificed," he said, explaining that he forfeited his own dreams and disappointed his father by failing to produce a son. He and his wife had one child, a daughter. But he said such forbearance benefitted the country, creating a bulge of working-age people with fewer dependents. The resulting burst in productivity was known as the demographic dividend. "I cannot imagine if we had 400 million more people in China," Yu said. \=/

But there had been serious abuses of the system. Villagers who can’t pay the fines complain that family planning officials confiscate their pigs and cattle and ransack their homes and even seize their children. Sometimes officials make regular visits looking for illegal children. “We were always terrified of them,” one villager told the Los Angeles Times.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “The family planning regulations were prone to abuse because local officials were often evaluated by their superiors based on how well they keep down the populations of their areas. There had been well-known cases of forced abortions or sterilizations across China. Last year, Chinese Internet users sympathized with the plight of Pan Chunyan, who said she had been abducted by officials in Daji Township when she was eight months pregnant with her third child. The officials forced her to had an abortion at a hospital. In June 2012, another woman, Feng Jianmei, was forced to abort a 7-month-old fetus in Shaanxi Province, in a case that also ignited national outrage. Parents in other parts of China had accused local family planning officials of abducting babies who were considered “extra” children in a household and selling them to orphanages, sometimes for $3,000 per baby.[Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, September 26, 2013]

Rewards for One Child Under the One Child Policy

Parents who had only one child got a "one-child glory certificate," which entitled them to economic benefits such as an extra month's salary every year until the child was 14. Among the other benefits for one child families were higher wages, interest-free loans, retirement funds, cheap fertilizer, better housing, better health care, and priority in school enrollment. Women who delayed marriage until after they were 25 received benefits such as an extended maternity leave when they finally got pregnant. These privileges were taken away if the couple decided to have an extra child. Promises for new housing often were not kept because of housing shortages.

In some cases families that obeyed the one-child policy rules received generous loans. Reporting from Xiamen, Kenneth R. Weiss wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “A 6-year-old girl with a bob haircut sat alone on an enormous wraparound couch, dwarfed by the living room furniture and a giant flat-screen TV. As she flicked the remote in search of cartoons, her parents pointed proudly to the recessed lighting and high ceilings. Then they proceeded with an official tour of their three-story house with white marble floors, oversized windows and a granite entryway flanked by a Corinthian column. [Source: Kenneth R. Weiss, Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2012]

"All of this was paid for with a $100,000 interest-free loan from the Chinese government, an incentive to keep the family's size "in policy." For these residents of a rapidly developing rural area, that meant sticking to two girls and giving up the chance to had a son. The husband, Zhang Qing Ting, an electrical technician, said living in a modern subdivision for in-policy families beats the usual cramped apartments with no garages. He and his wife, Chen Hui Ping, a factory worker, will also be eligible for cash payments when they retire. "Many of my friends envy me," Zhang said, mopping sweat from his neck as a dozen local officials and family planning bureaucrats looked on. The couple had been given a day off work to showcase the benefits of their restraint to two foreign journalists. Jin Jing, chairman of Chao Le village, summed up the message: "If you practice family planning, you could get this kind of reward."

Punishments for Extra Children Under the One Child Policy

The one-child program theoretically was voluntary, but the government imposed punishments and heavy fines on people who didn't follow the rules. Parents with extra children could be fined, depending on the region, from $370 to $12,800 (many times the average annual income for many ordinary Chinese). If the fine was not paid sometimes the couples land was taken away, their house was destroyed, they lost their jobs or the child was not allowed to attend school. Government employees risked losing their jobs if they did not adhere to the policy. Sometimes the punishments were more than a little bit over the top. In the 1980s a woman from Shanghai named Mao Hengfeng, who got pregnant with her second child, was fired from her job, forced to undergo an abortion and was sent to a psychiatric hospital and was still in a labor camp the early 2000s. There were reports that she had been tortured.

Into the mid 2000s, authorities in Shandong raided the homes of families with extra children, demanding that parents with second children get sterilized and women pregnant with their third children get abortions. If a family tried to hide their relatives were thrown in jail until the escapees surrendered. One woman who said she had permission for a second child told the Washington Post she was hustled into a white van, taken to clinic, physically forced to sign a form and was given a sterilization operation that took only 10 minutes. Another women told the Washington Post several of her relatives were thrown in jail when she was seven months pregnant and were denied food and threatened with torture and told they wouldn’t be released until the woman had an abortion. After she turned herself in, a doctor inserted a needle into her uterus. Twenty-four hours later she delivered a dead fetus. Another woman was forced to undergo a botched sterilization that left her with difficulty walking.

Sometimes the fees for a second child were jacked up for couples with high incomes. One woman who earned $127,000 a year with her husband told The Times she was told her fees for a second child would between $44,650 and $76,540. She ended up paying $5,000 to special agent to give birth in Hong Kong, where the one-child policy does not apply. Even high level officials were not immune from the policies. In April 2007, a Communist Party official in Yulin in Shanxi was fired for having too many children — three daughters with his wife and a son and daughter with his mistress. Some poor parents who broke the one child policy had were required to pay their fine with grain: 200 kilograms of unmilled rice

People Allowed to Have Additional Children in China

Lisu minority baby

In 17 provinces, rural couples were allowed to had a second child if their first was a girl. In the wealthy southern provinces of Guangdong and Hainan, rural couples were allowed two children regardless of the sex of the first. Urban couples, who were generally satisfied with small families, were generally restricted to one child. Officials softened the one child policy in rural area where children were needed in the fields and infanticide appears widespread as a result of the preference for boys.

Minority groups such as Tibetans, Miao and Mongols were generally permitted to had three children if their first two were girls. In the Yunnan, where many minorities live, the birth rate was 17 per 1,000 residents, compared to four per 1,000 in Shanghai and five Beijing, and 12 for the country as a whole. So many children were being born in Yunnan that the government was offering cash for school tuition and higher pensions to those who stick with the one child policy.

Urban parents were permitted to had two children if the husband and wife were only children.The number of marriages made up of only children was increasing but many were not taking up the option of having a second child. One Beijing couple with a two-year-old son told the Times of London, “It cost more than 35,000 yuan ($5,125) a year just to leave our baby in a kindergarten. Why spend this amount of money on a second?”

Parents of a child certified by a doctor as handicapped and couples with both members from single-child homes were also allowed to had an additional child. As children of single-child grow up they will be allowed to had more children. Parents who lost children in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake were allowed to had additional children. In March 2011, a Chinese embassy official said New Zealand should consider compensating the families of students who died in an earthquake in Christchurch. The official said the victims were not only the family’s only children but also future breadwinners, “You could expect how lonely, how desperate they are...not only losing loved ones, but losing almost entirely the major source of economic assistance after retirement.”

There was a sense of unfairness regarding the inconsistency in how the rules were applied and frustration over the waiting time for changes to take place. Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times: In some rural jurisdictions, people could had a second child if the first was a girl, but only after a waiting period. In other places, a second child was permitted if both parents were single children. Paperwork to obtain permission was cumbersome. The rules were bewildering. The Beijing News carried a story about a young couple who had to collect 50 pages of documents and receive permission from 10 of their nearest neighbors before they could get approval to had a second child. [Source: Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2012]

Skirting the One Child Policy

Families in rural areas, where children are needed to work family farms, were more likely to break family planning rules than urban families. Migrants to the cities were 13 times more likely to break family planning rules than urban residents. While the rules remained strictly enforced in large cities like Shanghai and Beijing, they were eased in medium-size cities and towns. By the mid 2000s, so many children had been born outside and within the rules, only one child in five was an only child.

To get around the one child policy, parents gave birth abroad or pretended their first child was s handicapped (loopholes allow them to have another legally) or got divorced and remarried. One entrepreneur had three successive “wives” in order to have more children. Some parents bribed doctors to document a second child as a twin to the first even though the second child was born years after the first one. There were stories about twins who were born 10 years apart. The practice was so common in the Guangzhou area that pregnant women were asked, “Is it your first child or are you having twins?” Others got approval for a “second first child” by giving birth in a hospital that had no record of their first child. Others “parked” second children with childless relatives or friends.

Extra children were often tolerated and documented as long as parents payed the fines for the extra children, which became to be viewed more as a fee than a fine. Depending on the place and the situation the fine can vary between $370 and $12,800. One man who raised $1,200 from his family to pay the fine for his second child told the New York Times, the authorities "didn't try to talk us out of it. They just wanted to be sure we would pay the fine." Evan Osnos of the New Yorker said he knew “a young guy from Hangzhou whose parents are farmers and they paid for his birth in grain.” As the Chinese economy grew, it became much easier to evade family planning officials as hundreds of millions of Chinese were not pinned to one place as they roamed around the country in search of jobs.

Undocumented Children in China

Additional children born to parents that had reached their one-child limit often had a rough ride. Some were denied a birth certificate and proper documentation, which severely affected them for the rest of their life. Without proper papers these children could not enter school, find work as adults or do most of anything legally. And remember this is China where proper documentation and authorization is of utmost importance and required for many things. Parents involved in illegal political or religious activities were sometimes punished by denying their children birth certificates and documentation, even if they have only one child. Many parents with more than two children didn’t declare all their children. A mother of three in a suburb of Beijing told the Independent she only declared her oldest child. "If I tell them the truth, are they going to reward me with a bonus?" she said. "Why invite trouble.”

As many as 13 million people were in legal limbo and unregistered in 2015 because they were born outside the one-child policy and not given crucial household registration documents — the “hukou” — necessary in China to obtain basic social services such as schooling, healthcare and housing. Even the state-rune China Daily said that these individuals were treated unfairly and should be allowed access the social services. ““These children are innocent of any wrongdoing and they should be granted the legal status that would enable them to access social resources,” an editorial in the newspaper said. [Source: Agence France-Presse, November 25, 2015]

“A Beijing woman, Li Xue, told AFP how she has been forced to live in the shadows due to the bureaucratic requirements. Her family was required to pay 5,000 yuan — far beyond the 100 yuan a month in benefits that her parents lived off. “Her mother said: “We’d have to go to the neighbors to beg for some medicine if she was sick.”

According to some estimates there were 6 million undocumented children in China in the mid 2000s. Most of them were believed to be girls. Many were the third of three daughters, who were sometimes referred to as "excess" children, and are secretly shuffled off to relatives. Undocumented children (also called "black permit" children) are children who are born and raised in secret and never registered with the government. To avoid detection by the Family Planning Association the children are shuffled around among uncles, aunts and siblings. Pregnant women who chose to hide in the countryside until they give birth are sometimes called "birth guerrillas."

Sui-Lee Wee wrote in the New York Times: When Chen Huayun, 33, was little, officials in her hometown in the eastern province of Jiangxi checked the laundry lines of houses for baby clothes, she said. Chen’s parents, who were civil servants, hid her or sent her to stay with her grandparents during school holidays because she was their second child. “This was considered an illicit birth, and it was never spoken of publicly, so they were not fined,” she said. “It was only when they retired that their colleagues knew that I existed.” [Source: Sui-Lee Wee, New York Times, May 13, 2021]

On the life of a second child under the One-Child Policy, a woman from Shenzhen told The New Yorker blog: “I have an elder brother. In our case, my parents felt even luckier that I am a girl, because a son and a daughter together forms the character “good.” My father was already working in Shenzhen when my mother was about to give birth to me in my father’s hometown located in northern Guangdong. After I was born, my father had to take a few days off to go back to his hometown and see me and my mother, and then he had to go back to work. My father had to lie to his boss at the time that he needed to take care of my grandmother. My parents did not want people to know that a second child was born. Five months later, I was brought to Shenzhen as well, and my parents had to say that I’m not their child, I’m my uncle’s child. It’s sort of a custom at that time and probably only in the Hakka community, that some children will be “claimed” by relatives because of poverty. My uncle, actually, has four children, but they all lived in the countryside.[Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, November 24, 2010]

Outrage Over Rich Chinese Family with Eight Babies and Zhang Yimou's Four Children

Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In America, a family with eight children is the premise for a reality television show. In China, it's a national scandal. The revelation that a Chinese couple were the proud parents of two sets of triplets and one set of twins launched a round of soul-searching about how the super-rich circumvent the one-child policy. It is a tangled case involving a wealthy couple, two surrogate mothers, a gaggle of nannies and, to top it off, a team of government bureaucrats scrambling to figure out how they all came together.

A spokesman for the Health Office in Guangzhou, where the family lives, said the case poses "huge ethical problems." The babies have stirred up fiery emotions on Chinese Twitter-like microblogs and Internet forums. "In this society, if you have money, you can have miracles!" one sardonic university student wrote on his Sina Weibo microblog. "Having children is now a luxurious game for the rich," wrote a user in Guangzhou, the southern city where the [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, January 19, 2012]

A southern Chinese newspaper broke the news that the couple had four girls and four boys with the help of the two surrogates and in-vitro fertilization. The newspaper had been alerted to the case by an advertisement for a local children's photography studio. In the photo, the babies, who were born in September and October 2010, sit in a line against a pink backdrop wearing identical pink onesies and pointy white hats. Little is known about the family, which has moved away from its home amid the uproar. According to the article, the parents had tried to naturally reproduce for years before paying a surrogacy agency $158,000 for the procedure.A reporter from China Central Television interviewed former neighbors, who recalled witnessing an "extremely spectacular scene" when the family strolled around the complex to catch some sun. One neighbor said that the couple had used an American doctor for the in-vitro fertilization.

Many details reported in the state press focused on the family's wealth. The parents hired a team of 11 nannies to look after the children, at a monthly cost of $16,000. For one set of babies' one-month birthday, the parents held a prize drawing in which they gave away eight bars of gold. An anchorwoman on China Central Television said the intersection of abundant wealth and abundant children has had a discomforting effect on Chinese society. "Where does this discomfort come from? It comes from unfairness," she said. "Why? Because the vast majority of us strictly abide by the one-child policy. One family, one household, one child." There has been some discussion of publicly shaming and creating “bad credit” files for rich and famous people who mock the one-child policy. One multimillionaire businessman in Beijing, with three children, said he wasn't worried about such threats. He told the Times of London: “I have plenty of money, and if I want to spend that money on having more children I can afford to.”

In May 2013, it was reported that Zhang Yimou, the celebrated film director and arranger of the 2008 Summer Olympics’ opening ceremony in Beijing, fathered four to seven children, an extreme violation of China’s one-child policy. The People’s Daily, the Communist Party mouthpiece, alleged that Mr. Zhang had fathered seven children with four different women. According to the New York Times reported,: The news has ignited an angry online debate, with Internet users condemning the unequal application of the one child policy. The truth is: for the rich, the law is a paper tiger, easily circumvented by paying a “social compensation fee” — a fine of 3 to 10 times a household’s annual income, set by each province’s family planning bureau, or by traveling to Hong Kong, Singapore or even America to give birth. [Source: Ma Jian, New York Times, May 21, 2013]

In December 2013, Zhang admitted having three children with his current wife, according to a studio media posting. In January 2014, it was announced that Zhang would be fined $1.2 million for having three kids beyond the one child limit.

See Separate Article Outrage Over Zhang Yimou’s Extra Children factsanddetails.com

Chinese Couple Paid $155,000 in Fees to Have Seven Children

Katie Warren wrote in Business Insider: A Chinese couple paid $155,000 in fees in order to have seven children Mandy Zuo reported for the South China Morning Post. Zhang Rongrong, a 34-year-old businesswoman, and her 39-year-old husband have five boys and two girls between one and 14 years old, Zhang told the Post. In flouting China's two-child policy, the couple had to pay their local government "social support fees." Otherwise, their additional children wouldn't have been able to receive government identity documents. [Source: Katie Warren, Business Insider, February 25, 2021]

“Zhang, who runs skincare, jewelry, and garment companies in the Guangdong province in southeast China, told the Post she wanted multiple children so that she never had to be alone. “When my husband's away on trips and the older kids are also away for study, I still have other children around me …" she said. "When I'm old, they can visit me in different batches." “She told the Post that their seventh would be their last child because her husband had a vasectomy in 2019. She added that she made sure she was financially stable before having the younger children and that her kids were all "very happy."

“These fee amounts vary by location and are typically based on local income, according to the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. China does appear to strictly enforce payment of these fees. “Last year, a Guangzhou couple's bank accounts were frozen as the court ordered them to pay $45,000 for having a third child, according to the Global Times, an English-language Chinese newspaper. The couple said paying the fee was not feasible because their monthly income was only about $1,550. Local authorities suggested the couple pay the fine in multiple installments.”

Costs of the One-Child Policy: Too Many Boys and Unregistered Children

According to Encyclopedia of Sexuality: By the mid-1990s, the “one-child policy” had produced an obvious but unintended and serious sex imbalance. The traditional preference for sons coupled with the “one-child policy” led to ultrasound scans during pregnancy followed by selective abortion for female fetuses. In January 1994, a new family law took effect that prohibited ultrasound screening to ascertain the sex of a fetus except when needed on medical grounds. Under the new law, physicians could lose their license if they provide sex-screening for a pregnant woman. Even after birth, “millions of Chinese girls had not survived to adulthood because of poor nutrition, inadequate medical care, desertion, and even murder at the hands of their parents”. [Source: Zhonghua Renmin Gonghe Guo, Fang-fu Ruan, M.D., Ph.D., and M.P. Lau, M.D. Encyclopedia of Sexuality hu-berlin.de/sexology =]

The 1990 census showed about 205 million Chinese over the age of 15 were single in a total population of 1.2 billion. Overall, three out of five single adults were male. However, government figures show that, while the vast majority married before they turned 30, eight million Chinese in their 30s were still single in 1990, with men outnumbering women by nearly ten to one. Demographics suggesedt that by the year 2000 tens of millions of Chinese men would be unwilling or willing lifelong bachelors. On the negative side, Chinese sociologists and journalists suggested that the drastic increase of unwilling bachelors in a society that values the family and sons above all else may well produce an increase in prostitution, rape, and male suicide. Bounty hunters had already found a lucrative market for abducting young city women and delivering them to rural farmers desperate for brides.

Then there was the issue of unregistered children born secretly. Anita Chang of AP wrote. Children born in violation of the country's urban one-child policy, many of whom were unregistered and therefore have no legal identity, could number in the millions. The government has said it would lower or waive the hefty penalty fees required for those children to obtain identity cards, though so far there has not been much response to the limited amnesty. Many say they have been reassured by the government's declaration that information cannot be used to levy fines, which often run as high as six times an annual income for extra births."This was only about statistics, but people were worried that they could get fined for having an extra child and they'll avoid the census," Duan Chengrong, head of the population department at Renmin University told AP. "Like in the U.S., the Chinese these days were paying more attention to their privacy." .” [Source: Anita Chang, AP, September 3,2010]

China is now facing a critical shortage of laborers and an aging population caused to a large degree by the One Child Policy. In 2012 the working-age population of China shrank for the first time, threatening a mainland economic miracle built upon a pool of surplus labor. People over 60 now make up 18 percent of China's population.

See Separate Article SERIOUS PROBLEMS WITH THE ONE-CHILD POLICY: FORCED ABORTIONS AND STERILIZATIONS, ATTACKS AND HARRASSMENT factsanddetails.com ; ABDUCTED CHILDREN AND THE ONE CHILD-POLICY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; DEMOGRAPHIC ISSUES IN CHINA: AGING POPULATION, BIG PENSION PAY OUTS, LABOR SHORTAGES AND SLOWED ECONOMIC GROWTH factsanddetails.com

Dilemma of Grown-Up One-Child Policy Children: Where to Spend New Year

During the Chinese New Year hundreds of millions of people pack the trains and highways to return to their home towns. But, Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “for one particular group — young urban married couples who grew up as only children — the yearly ritual could also mean tough decisions, sometimes-painful arguments and a modern-day test of one of China’s centuries-old family traditions. [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, January 18, 2012]

These young couples were part of the generation of only children born during the 34 years of China’s “one-child policy.” Following the typical pattern, they migrated to the larger cities from the outlying provinces to go to university. They stayed for work and then got married. And now they must decide which set of parents to visit. It’s a decision fraught with emotion, especially for China’s growing elderly population, often living alone and far from their children, who historically had been caregivers in a country with little social safety net.

“Both of us want to go back to our home to celebrate Chinese New Year,” said Lin Youlan, 30, a government worker who married her husband, Li Haibin, 33, four years ago. “We always fight about this problem.” She was from Chongqing in southwest China, and he was from Shandong, on China’s east coast. They live in Beijing, and they were only children. As the only son, Li was under intense pressure to visit his parents, who were not in good health. “In Shandong province, men must celebrate the Spring Festival with their own families. And the wives should spend the Lunar New Year at their husbands’ homes,” he said. “I worry how others will look at my parents if I don’t go back home every year.” Traditionally, the Lunar New Year’s Eve and the first day of the new year were spent at the home of the husband’s parents, and the second day was spent with the wife’s. But in those days, married couples largely came from the same village or town or a relatively short distance apart.

One-Child Policy a Surprising Boon for China’s Girls

Alexa Olesen of Associated Press wrote, “Tsinghua University freshman Mia Wang has confidence to spare. Asked what her home city of Benxi in China's far northeastern tip was famous for, she flashes a cool smile and says: "Producing excellence. Like me." A Communist Youth League member at one of China's top science universities, she boasts enviable skills in calligraphy, piano, flute and ping pong.” Such gifted young women are increasingly common in China's cities and make up the most educated generation of women in Chinese history. Never had so many been in college or graduate school, and never had their ratio to male students been more balanced. To thank for this, experts say, was three decades of steady Chinese economic growth, heavy government spending on education and a third, surprising, factor: the one-child policy. [Source: Alexa Olesen, Associated Press, August 31, 2011]

"In 1978, women made up only 24.2 percent of the student population at Chinese colleges and universities. By 2009, nearly half of China's full-time undergraduates were women and 47 percent of graduate students were female, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. In India, by comparison, women make up 37.6 percent of those enrolled at institutes of higher education, according to government statistics. Many single-child families were made of two parents and one daughter. With no male heir competing for resources, parents had spent more on their daughters' education and well-being, a groundbreaking shift after centuries of discrimination. "They've basically gotten everything that used to only go to the boys," said Vanessa Fong, a Harvard University professor and expert on China's family planning policy.

See Separate Article CHINESE WOMEN: STATUS, STATISTICS, GENDER ROLES AND VILLAGE LIFE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ Beifan ; Wikicommons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021